Zohran Mamdani campaigned on, among other things, making halal street meat $8 again—a rare moment when the democratic socialist broke with his own ideology and embraced the truth: New York’s high prices aren’t a law of nature but the product of a city that smothers commerce in permits, mandates, and red tape. The same forces that make a $400 vending permit into a $22,000 black-market asset also inflate the cost of everything from rents to haircuts. New Yorkers pay more because doing business here costs more, thanks to a regulatory thicket, heavy taxation, and an enforcement regime that treats entrepreneurs as revenue sources rather than civic partners. Mamdani may understand this when it comes to food carts, but unless he is willing to apply market-friendly reforms across the board, the city’s affordability crisis will only deepen.

The halal-cart economy illustrates this dynamic vividly. Vendors sell $10 trays of rice and meat not because the ingredients have soared in price but because the city caps street-vending permits at artificially low levels. Unable to obtain the $400 permit directly, many vendors pay the vastly larger sum on the secondary market. They estimate that if permits were affordable and available, a platter would cost closer to $8. Mamdani’s pledge to make street meat affordable again acknowledges a reality that extends far beyond sidewalk food: New York’s regulatory structure routinely inflates prices by limiting supply, raising barriers to entry, and driving up operating costs.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The Mercatus Center ranks New York as the second-worst state for red tape on businesses, behind only California. That ranking doesn’t even account for the additional layers imposed by the city itself. Some of the rules reflect the nature of commerce in New York, especially the dense oversight of financial services—an industry that, for now, remains largely city-based. But many rules hit small businesses unrelated to finance—restaurants, barbershops, retail stores, child-care centers—where margins are thin and compliance costs loom large. New York has triple the national average of regulations governing education and more than twice as many governing social services. In a 2025 Public Policy Institute of New York survey, business owners overwhelmingly identified reducing regulations, followed by business taxes, as the most important steps that policymakers could take to help them survive.

Labor regulations add further strain. The steep cost of living already forces employers to pay higher wages than elsewhere. Layered on top are rules requiring salary-range postings, bans on questions about past pay and criminal histories, expanded sick leave, restrictions on scheduling and on firing for cause, and a higher minimum wage: currently, $16.50 an hour. Employers also cannot use AI tools to screen job applications unless the software undergoes a “bias audit.” “Ban the box” policies, meant to help applicants with criminal records, have been shown to increase discrimination as employers search for proxies—most troublingly, race—to infer a prospective employee’s background. New York also has the nation’s fourth-highest workers’ compensation expenditure, 64 percent above the national average. These policies raise labor costs, impede hiring, and hinder the matching of workers to jobs, making an already-expensive labor market even less dynamic.

“One in five workers must get a license, paying fees and often losing weeks or months to mandated training before beginning to earn income legally. ”

Starting a business is equally challenging. The first obstacle is often simply finding a space. Strict zoning regulations limit where businesses may operate and frequently force entrepreneurs to seek variances or zoning changes to adapt to shifting markets. A bicycle-rental shop losing customers to Citi Bike and looking to pivot its business to bike repair may be barred from doing so without a zoning modification, a slow and expensive process. Onerous building codes extend renovation timelines, leaving new businesses paying months of rent before they can legally open their doors.

Licensing is a major hurdle. New York maintains dozens of occupational-license categories—more than most major cities—including for hair and nail services, food preparation, and contracting. One in five workers must get a license, paying fees and often losing weeks or months to mandated training before beginning to earn income legally. These requirements slow business formation and disproportionately burden lower-income New Yorkers seeking upward mobility through entrepreneurship.

Once a business opens, surviving the enforcement regime becomes its own challenge. As many business owners acknowledge, it’s nearly impossible to operate in New York without running afoul of some obscure rule. The city polices everything from dancing in venues not officially licensed for dancing to how trash gets stored, the cleaning of sidewalks, the health grades of restaurants, and the exact placement of signage. During the pandemic, small businesses were slapped with heavy fines for “price gouging” when they raised prices to reflect the skyrocketing cost of securing basic goods. In 2015, the city collected $2 billion in fines and fees; by 2024, business fines alone had exceeded a quarter of a billion dollars.

Business taxes are notoriously high. Commercial tenants in Manhattan south of 96th Street pay a 6 percent occupancy tax on their base rent—an extraordinary levy that further disadvantages brick-and-mortar retailers. As Mamdani pushes to expand street vending, these fixed businesses will face even steeper competition, despite shouldering far higher regulatory and tax burdens.

Unsurprisingly, New York’s one-year business failure rates exceed the national average. These barriers don’t just raise costs for consumers; they deepen inequality by making business formation prohibitively expensive for all but the well-capitalized.

Mayor Eric Adams achieved modest progress in making New York friendlier to entrepreneurs with his 2024 City of Yes for Economic Opportunity initiative, which updated zoning rules to make it easier for small businesses to open, expand, and adapt. But deeper structural problems remain.

The question is whether Mamdani will extend his deregulatory instincts beyond halal carts. He clearly recognizes, in this case, that regulation inflates prices and restricts opportunity. Yet his broader progressive commitments—more employer mandates, stronger unions, a dramatically expanded public sector—push in the opposite direction. Consider his proposal nearly to double, by 2030, the city’s minimum wage to $30, a level approaching the current median wage. Thousands of businesses that rely on low-skill labor would shut down. All the street permits in the world wouldn’t make up for doubling labor costs. And Mamdani’s ambitious spending plans will deepen the city’s dependence on fines—the easiest way to raise revenue without seeking Albany’s approval.

If he is serious about affordability, Mamdani must recognize that the problem does not begin and end with small businesses or politically sympathetic sectors. Big-box retailers and national chains, businesses that he has targeted rhetorically, are essential to lowering prices because they achieve economies of scale. Yet zoning restrictions cap store sizes and prevent these efficiencies from reaching New Yorkers.

New York could be far more affordable—but only if it lets businesses of every size operate, adapt, and earn a profit. As long as the city keeps piling on regulations, delays, fines, fees, wage mandates, and hiring restrictions, prices will keep going up. And those costs will weigh, as they always do, on the hardworking New Yorkers whom Mamdani says he wants to help.

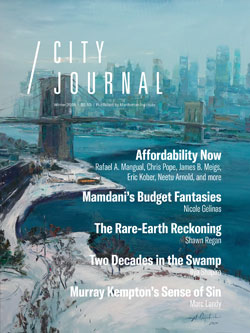

This article is part of “An Affordability Agenda,” a symposium that appears in City Journal’s Winter 2026 issue.

Illustration by wildpixel/Getty Images