Imagine a single policy change that could lower food prices, free up land for construction or conservation, improve the environment, cut greenhouse-gas emissions, and reduce fuel costs. You’d think that it would be a no-brainer, especially now, when “affordability” has become the watchword for both parties. And it wouldn’t require a new tangle of regulations or an expanded federal bureaucracy. To the contrary: it would simply mean ending the Environmental Protection Agency’s Renewable Fuel Standard—the byzantine, two-decade-old program that forces refiners to blend plant-based biofuels into nearly every gallon of gasoline and diesel sold in the United States.

In this imaginary world of rational policy, the White House would order the EPA to roll back the RFS immediately, and Congress would vote to kill the program for good. In the real world, though, such commonsense reform currently stands little chance. Despite two decades of criticism, the RFS persists because its political math is irresistible.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Included as part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (and expanded two years later), the RFS rules were meant to curb emissions and boost the supply of domestically produced fuel. Instead of importing more oil, the logic went, we could pay farmers to grow more soybeans (for biodiesel) and corn (to be converted into ethanol and blended into gasoline).

But the RFS program fails on its own terms. For example, EPA rules effectively require that automotive gasoline sold in the U.S. contain 10 percent ethanol. But that addition doesn’t increase the nation’s gasoline supply by 10 percent. The amount of energy contained in a gallon of ethanol, it turns out, is only slightly higher than the fossil-fuel energy needed to grow and process the corn that produces that ethanol.

In other words, rather than creating new domestic energy, the RFS merely converts fossil fuels—through a messy agricultural process—into a roughly equivalent quantity of biofuels. There’s only a modest net gain. Worse, the program inflates wholesale corn and soybean prices by creating artificial demand for those crops. And because corn and soybeans are major food ingredients—including as feed for cattle, pigs, and chickens—that demand ultimately drives up grocery bills.

Most people use the word “renewable” as a synonym for “environmentally friendly.” But it’s now clear that renewable biofuels are an environmental disaster. More than 20 million acres of cropland are devoted to corn-ethanol production, for example, which increases fertilizer and pesticide runoff. Without the mandated demand for ethanol, much of that land would remain as wild habitat or be available for other human needs. Nor do biofuels reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. A 2022 Department of Energy report concludes that “the carbon intensity of corn ethanol produced under the RFS is no less than gasoline and likely at least 24 percent higher.”

On the other hand, the RFS program succeeds brilliantly in funneling billions of dollars from motor-vehicle drivers to farmers and agricultural processing giants such as Archer-Daniels-Midland. Instapundit blogger and University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds was on the money when he dubbed corn-based ethanol “liquid pork” back in 2007. According to the Renewable Fuel Association, a pro-biofuels trade group, roughly one-third of the corn grown in the U.S. is destined for gas tanks. Last year alone, the group said, ethanol refiners purchased $23 billion in American corn. On top of this, nearly half the soybean oil produced in the U.S. gets converted into biodiesel. Combined, the ethanol and biodiesel industries had revenues of nearly $50 billion in 2024.

The renewable fuels program is best understood using a management adage: “The purpose of a system is what it does.” What the RFS does is levy an invisible tax on drivers, which, in turn, funds a roundabout subsidy to farmers and agribusiness processors. Drivers filling their tanks might not realize how much of their fuel dollar gets diverted into this inefficient scheme, but farmers and refiners watch every penny. And their representatives on Capitol Hill fight to defend the biofuel revenue stream. The RFS is, in other words, a classic policy with a concentrated group of beneficiaries and a larger, diffuse group of payers mostly unaware that they’re footing the bill. Farm states, with small populations, wield outsize influence in the Senate; and let’s not forget that nearly every presidential hopeful starts campaigning in Iowa, the nation’s top corn-producing state.

For the moment, the Trump administration is not only behind the biofuels program but also trying to expand it. Earlier this year, for example, the EPA issued a temporary “emergency” waiver raising the amount of ethanol that refiners could blend into gasoline. During warm months, the agency traditionally caps ethanol levels at 10 percent in order to limit smog caused by the alcohol’s volatility. The waiver allowed refiners to sell E15—gasoline with 15 percent ethanol—throughout the summer. (For mind-numbingly complex reasons, EPA regulations effectively force refiners to maximize ethanol blending, so what’s supposed to be a “ceiling” often operates more like a floor.) Now the White House is pushing legislation to make year-round E15 sales permanent, a move the petroleum industry opposes.

The administration has proposed other sweeping changes meant to boost U.S. biofuel production, including a 67 percent increase in the mandated volume of biodiesel. While requiring dramatically higher levels of biofuels in the products that petroleum marketers sell, the White House also wants to restrict their ability to import plant-based fuels to fill the gap. Breakthrough Institute agricultural analyst Dan Blaustein-Rejto sees the proposed policy as “an attempt to make U.S. agriculture less export-dependent and to mitigate the damage done by the U.S.–China trade conflict.” American corn and soybean farmers depend heavily on exports. When China responded to Trump’s “liberation day” tariffs by halting its massive imports of U.S. soybeans, that left farmers “hanging out to dry,” Blaustein-Rejto commented.

The White House hoped it could make farmers whole by forcing fuel companies to buy up the excess supply. But refiners and analysts warned that the supply chain can’t handle such an abrupt shift. In the end, Trump ratcheted down his trade demands and China made a dubious promise to buy more U.S. soybeans. But the chaotic process left both farmers and fuel companies rattled. In late November, the administration hinted that it might delay its biofuel demands for a year or two.

What if the Trump administration were instead to reverse course and roll back the RFS requirements? In the short term, such a move would be devastating to farmers already whipsawed by Trump’s gyrating trade policies. But a multiyear plan to wean farmers off the RFS crypto-subsidy would almost certainly bring down consumer food prices in the long run.

It’s hard to say exactly how much the RFS rules have swelled grocery bills in recent years. But a 2023 EPA study concluded that 2023–25 biofuel requirements would raise overall food prices by $4.9 billion to $6.8 billion. A 2025 EPA study predicted that the Trump administration’s expanded biofuel plan would raise food expenditures by another $2.4 billion. Other biofuel studies have found even greater impacts on consumer prices. Given that grocery prices have shot up more than 30 percent since 2020, any rollback would be welcome.

Biofuels also push up the cost of driving, though for a subtle reason that’s easy to miss. Biofuel backers often brag that a gallon of ethanol usually costs a few cents less than a gallon of gasoline. But ethanol contains 33 percent less energy than gasoline, by volume. That means that a car that gets 30 mpg will be able to drive only 20 miles on a gallon of ethanol. So while dropping the ethanol requirement would not bring down the price of fuel, it would significantly reduce the cost of driving.

Nearly two decades after Glenn Reynolds coined the phrase, the liquid-pork pipeline is pumping more furiously than ever. Despite the political challenges, RFS critics should not stop fighting this wrongheaded policy. At the least, the issue drives home the key lesson that any government program favoring a particular interest group will tend to become locked in, even when it proves harmful for most Americans. Voters should be wary of similar, superficially appealing proposals today. (Fans of New York mayor Zohran Mamdani’s rent-freeze plan, take note.) At the best, the issue could unify an unlikely coalition that would include environmentalists, lawmakers from fossil-fuel-producing states, and affordability advocates from both parties.

The RFS hurts consumers at both the grocery store and the fuel pump. It reduces habitat, causes runoff, and worsens emissions. In the end, it even hurts farmers. American farmers are the most productive in the world, Blaustein-Rejto notes: “Without RFS, corn and soy would be cheaper, and U.S. farmers would have even more of a competitive advantage internationally.” Though the transition might be tough, farmers would ultimately benefit from being free to plant according to market demand rather than shifting government priorities. The Trump administration has tried to micromanage the agricultural economy through top-down control. The result is backfiring on farmers and consumers alike.

The U.S. needs a freer market in food and fuel. Affordability is just one of several good reasons to let the sun set on the failed RFS experiment.

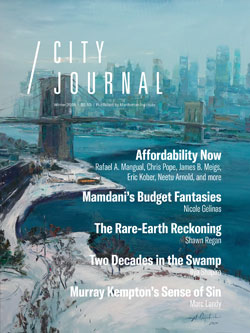

This article is part of “An Affordability Agenda,” a symposium that appears in City Journal’s Winter 2026 issue.

Photo: More than 20 million acres of cropland are devoted to corn-ethanol production. (Alyssa Schukar/Redux)