Until shortly before the coronavirus pandemic, real electricity costs for most American families had been declining for a decade. From 2009 to 2019, the fully loaded cost—that is, the total price per kilowatt-hour including generation, transmission, distribution, and surcharges—rose from 11.5 cents to 13 cents, an increase of 13 percent, well below the 19 percent growth in the Consumer Price Index. Despite inflation, the average annual national rate even ticked down in a few of those years.

That changed in 2019. From that year through 2024, residential rates jumped 27 percent (faster than inflation) to an average of 16.5 cents nationally. These recent price shocks have not been evenly distributed. Most states still saw rates rise more slowly than CPI, meaning that they fell in real terms. The fully loaded cost of a kilowatt-hour today varies more than ever. In 2024, it ranged from 11.5 cents in Nebraska, Idaho, and North Dakota to 29.4 cents in Massachusetts, 32 cents in California, and 42.9 cents in Hawaii.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Much of the rise in the national average stemmed from California’s eye-watering 67 percent increase, the nation’s biggest.

The next largest hikes, as a percentage of 2019 rates, were in the District of Columbia, New York, Maryland, and Maine—all at 36 percent, or roughly 50 percent above inflation.

Electric bills pose a special hazard for the political class because they serve as monthly reminders of policy failure. Public officials scramble to show that they’re “doing something.” New Jersey governor-elect Mikie Sherrill, for instance, has called for rate freezes. Utilities remain a favorite scapegoat for state legislators, even as their rates (and profits) remain tightly regulated by those same states. Some populists, meantime, blame data centers for consuming massive quantities of electricity. But today’s high prices stem from decisions made years ago by governments and the utilities they regulate. Much of the recent increase was purposeful—indeed, avoidable—and the worst is likely still to come.

Electric rates have two main components: the cost of generating power; and what transmission and delivery companies—mostly utilities—are paid to deliver it. For most of the past century, this boiled down to a single rate set by a local electric monopoly, with the blessing of state utility regulators.

Beginning in the late 1990s, deregulation swept the country as many states, including New York, Texas, and California, required utilities to sell off their power plants. Generators would compete in newly created wholesale markets, while utilities focused on maintaining and operating their parts of the grid. The new landscape attracted fresh capital, with high prices serving as a beacon for investment where the need was greatest. Much of the added capacity came from natural-gas plants, taking advantage of the vast new supply unlocked by the fracking boom.

Gas fueled a transformation in American power generation. In 2008, half of U.S. electricity still came from coal, while natural gas and nuclear each provided about 20 percent. By 2024, gas was supplying 42 percent of the grid, and coal had fallen to just 16 percent.

The consumer benefits of cheap gas obscured the extent to which state governments, prodded by environmentalists, were deliberately making electricity more expensive. One method was requiring power plants to pay for their carbon-dioxide emissions through “cap-and-trade” programs. Ten Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states, including New York, participate in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI).

The cost of these allowances has surged in recent years. In 2019, the four RGGI allowance auctions brought in $284 million. The four most recent rounds took in $1.4 billion, with costs passed on to ratepayers and the windfalls flowing to state governments to divvy up. New England’s grid operator, ISO–NE, estimated that RGGI compliance pushed up prices from gas plants (the region’s main power source) by 0.7 cents to 1 cent per kilowatt-hour.

California and Washington also operate emissions-allowance systems for fossil-fuel power plants. California’s grid operator estimated that the requirement added roughly 1.6 cents per kilowatt-hour “for a relatively efficient gas unit” in 2024.

All nine mainland states where residential electric rates have risen by 4 cents or more since 2019 were either part of RGGI or California. These gas-related up-charges weren’t the only factor, but they undeniably work at cross-purposes with the affordability concerns that many governors now voice.

Another driver of rising electricity costs is nuclear-power subsidies. The low gas prices of the 2010s prompted five states—New York, Ohio, New Jersey, Illinois, and Connecticut—to craft subsidy deals for nuclear plants that had previously been profitable. The cost of that assistance, about $500 million for New York in 2024, was passed along to customers.

More states have enacted renewable-energy mandates, requiring utilities and large customers to pay premiums for projects that often wouldn’t be built otherwise, even with separate federal subsidies. The solar panels now tiled atop upstate New York farmland are a vivid example. Beyond closing that price gap, adding new renewables—especially in remote areas—imposes additional interconnection and transmission costs, which states expect utilities to absorb and then “recover” through rate cases.

Intermittent renewables have distorted electricity markets. Grid operators need additional plants connected and ready for times when wind lulls or clouds cut output. That is capacity that must be paid for—which ultimately drives up costs.

Especially over the last decade, state governments have pushed for what can fairly be described as the biggest transformation of the grid since the last rural homes got electric lights after World War II.

Skyline-defining power plants sending high-voltage transmission lines to the horizon are no longer the grid’s defining image. The rise of “behind-the-meter” generation, particularly rooftop solar, means that electricity is now flowing both to and from homes. That shift has changed how much energy utilities deliver from power plants and, with it, how the costs of running local distribution networks get allocated. Ratepayers have gone from simply maintaining the grid to underwriting its transformation.

The Washington Post reported last October that supply prices had fallen, in nominal dollars, by 35 percent since 2005 (chiefly between 2010 and 2020) but that transmission and distribution charges had more than doubled, up 141 percent and 181 percent, respectively. Falling supply costs concealed rising delivery expenses, until they couldn’t.

Part of the increase in delivery expenses reflects utilities facing the same inflationary pressures as their customers. Utility wages rose—and with them, utility delivery rates. But utilities’ role was also changing almost as much as the grid itself, as companies were pushed out of the generation business and pulled deeper into the climate-industrial complex.

Even before Covid, utilities’ capital expenditures were rising faster than inflation. They leaped 44 percent between 2019 and 2024, an Edison Electric Institute review found. Covid disruptions made grid hardware scarcer—and more costly. The Producer Price Index for electric transformers, measuring the price of producing key grid-related components, surged more than 60 percent in 18 months, starting in late 2020.

The price of state and federal efforts to reconfigure electricity supplies has spilled far beyond generation alone and into the rising outlays for transmission and distribution. Demand for hardware—and the associated charges—has been driven up by state climate policies. Utilities in states with aggressive mandates are now accommodating more interconnections from small generators (mostly wind turbines and solar panels) than ever before. New York alone has approved more than $8 billion in transmission upgrades, prompted almost entirely by its 2019 climate law. The deluge of state and federal subsidies encouraged developers to build more projects—especially rural wind turbines—than the grid could readily receive. Residential customers bear the bulk of the expense.

“Too much of the permitting process depends on who is in the White House and whether he roots more for oil exploration or for offshore wind.”

Some of these programs, such as energy-efficiency incentives, can theoretically pay for themselves by “shaving” the amount of generation needed to meet peak demand for just a few hours in the hottest afternoons each summer. In other cases, though, the delivery charge becomes a vehicle for adding new expenses. It is a handy mechanism—an alternative to raising state taxes—for making people fund initiatives that policymakers want but prefer not to budget for, such as shifting customers to electric heat pumps (which, in turn, increase grid demand).

Climate policy is a major driver of rising electricity charges but isn’t the only one. Recent bills have also climbed as utilities recover the cost of uncollectible accounts. Arrears have always existed, but they swelled in 2020, first as households fell behind and then as states blocked utilities from disconnecting nonpaying customers. Nationally, households remain more than $15 billion in utility arrears, up from $10 billion in early 2022. As these balances become officially uncollectible, the burden will shift to other ratepayers. On top of that, states are experimenting with new forms of income-based electricity pricing, which will discourage conservation while pushing up other customers’ costs.

How can we make electricity more affordable? It starts by identifying Public Enemy Number One: uncertainty.

Fortunately, strong interest remains in generating and delivering electricity more efficiently, and opportunities abound. New or upgraded power plants and transmission lines remain attractive investments, especially as older coal facilities retire. But many projects never get off the ground because the path from approval and construction to interconnection and operation is so murky.

The arduous process for federal permitting, including environmental reviews under the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), hinders major interstate transmission projects that would better connect generation with the places where it is needed. The duration of reviews has lessened in recent years, but most still take more than two years to complete. Litigation remains a preferred, and effective, weapon for project opponents.

Too much of the permitting process depends on who occupies the White House and whether he roots more for oil exploration or for offshore wind. The June 2023 debt-ceiling legislation made modest changes to narrow the scope of certain NEPA reviews, but more can be done, including stricter limits on when lawsuits can be filed and steps to create more predictability in the system.

At the state level, unattainable climate targets—such as New York’s plan to more than double its renewable generation in the next five years—are preventing new, more efficient gas plants from replacing older, less reliable units. Several states have begun recognizing that they are purposefully making electricity less affordable in pursuit of objectively unreachable greenhouse-gas reduction goals. These choices often conflict with other state priorities, including affordability and reliability. States can relax such targets (some immediately) to ease rate pressures.

As for natural gas, Congress could curb states’ ability to misuse the Clean Water Act. New York has invoked the law to block pipelines serving New England, where gas-starved power plants must switch to burning oil on the coldest winter days. Setting aside the broader trade-offs involved in reducing emissions, some state legislatures have also adopted “carbon-free” or “zero-emissions” rules for the electric sector that would require power plants to stop using natural gas as soon as 2040. These deadlines create major obstacles for siting or financing more efficient plants that could not just lower costs but also improve reliability and reduce emissions in the meantime.

States have also increased expenses by mandating specific technologies within the broader category of renewables. New York, for instance, has committed its utilities and large customers to subsidizing 9,000 megawatts of offshore wind—arguably the least economical form of generation and one that would necessitate the addition of almost unimaginable amounts of battery storage for periods when the turbines don’t spin. Instead, states should take a more pragmatic approach to adding zero-emissions resources. A technology-agnostic framework, along with a freeze on mandatory renewable-purchase volumes, would ease upward pressure on electric rates, since new projects typically arrive with a fresh invoice for subsidies.

State lawmakers like using utilities as political punching bags, and utilities that punch back do so at great risk to their ability to operate. The result is predictable: utilities often agree to play the villain and the bagman, collecting funds and carrying out tasks that lawmakers don’t want to vote for, secure in the knowledge that their rate hikes will be approved. New Yorkers would be surprised to learn that the state’s energy agency holds more U.S. Treasury bills ($1.9 billion) than some banks, chiefly because it has been collecting money indirectly from electricity customers faster than it can be spent. That’s only possible because customers can’t see it happening.

An immediate, and overdue, step that state governments could take is fully to disclose how much their own policy choices are inflating electric bills. States should allow, and perhaps oblige, utilities to be more forthright about how much of a customer’s bill reflects market conditions, how much results from government mandates, and how little of the remainder represents actual profit. At a minimum, utilities should itemize the premiums that customers pay for RGGI or other emissions programs, the outlays for energy credits and subsidies, and the added cost from transmission or other grid build-outs required by state climate goals.

No state tells ratepayers the full story, though a few have made halting moves toward transparency. Connecticut, better than most, now breaks charges into four buckets: supply, federally regulated transmission, local distribution, and a “public benefit” line that includes its power-purchase deal with the Millstone nuclear plant. New York went in the other direction. In 2017, it barred utilities from showing the price of nuclear subsidies, and it has kept most renewable-energy expenses out of sight as well.

Without reform, the price pressures will only intensify. Near-total electrification—New York’s goal, and that of several other states—will require more than doubling the power delivered to some regions that still rely on fuel for home and building heat. Customers will keep receiving utility bills that feel too high and explain too little. But the utility is only the messenger, not the culprit. The real authors of those bills are the elected officials who designed, and still want, the system to work this way.

This article is part of “An Affordability Agenda,” a symposium that appears in City Journal’s Winter 2026 issue.

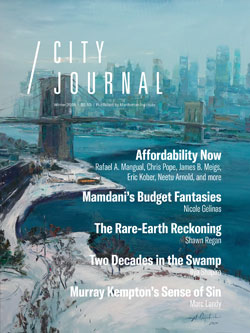

Photo: Nationally, residential electricity rates jumped 27 percent from 2019 to 2024—with some states showing much greater increases. (Dominic Gentilcore/Alamy Stock Photo)