Recent headlines give the impression that it’s dangerous to be a cop right now. In just the past six months, we’ve seen a Baltimore police officer ambushed and shot dead in her cruiser, a Houston cop shot by a serial felon during a routine traffic stop, an NYPD officer slashed with a machete, and dozens more attacks on law enforcement officials.

New data from the Fraternal Order of Police, a national law-enforcement union, suggest that these incidents are part of a larger trend. According to the FOP, 123 law-enforcement officers were shot in the line of duty this year through May 1, a 35 percent increase relative to the first five months of 2021. Nineteen of those officers died. The FOP believes that this year may turn out to be even worse than 2021, when 346 officers were shot and 63 killed by gunfire.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

These figures offer just a snapshot of the past 18 months, but the long-run data also suggest that policing has indeed gotten more dangerous since 2020, reversing its dramatic decline after violent crime hit a peak in the 1990s.

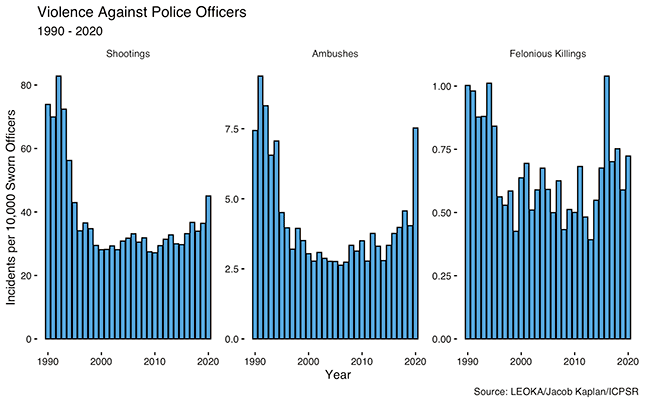

The FBI tracks violence against police officers through its Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) program. Using those data, the chart above shows the number of shootings, ambush attacks, and felonious (that is, non-accidental) killings of police officers between 1990 and 2020, adjusted for the total number of sworn officers reported that year. Both shootings and ambushes show a clear decline and then an uptick; while the data on actual killings is less useful, it also shows a similar trend.

Data published by LEOKA suggest that officer killings, at least, got worse in 2021, rising to 73 felonious killings versus 46 in 2020. The FOP and LEOKA data aren’t really comparable—they report different numbers for the overlapping years—but the trend in the former suggests that we should expect to see similar rises in shootings and ambushes once the full data for 2021 are available. Those ambushes, like the aforementioned murder of Baltimore officer Keona Holley, have attracted particular attention; the Department of Justice has raised concerns about such attacks as far back as 2015.

A simple way to understand these trends is that they mirror the increase in violent crime—principally homicides and shootings—that has gripped the country over the past two years. As violence on the streets increases, one would expect that cops would be more under threat.

But the surge in ambush-style attacks is reason to think that there may be a second effect, whereby offenders are not only more violent in general but also feel less inhibition in attacking cops directly. Increasing hostility toward the police, particularly from civilian leadership, may give offenders more of a sense that they can get away with assaulting officers while also suggesting to officers that they will face administrative and reputational consequences for defending themselves. That was how Chicago police framed one cop’s 2016 decision not to defend herself during a vicious beating: they said that she feared media retribution for fighting back against a black man.

Advocates of “defunding” the police often like to note that policing is less dangerous than many other jobs—it has a lower injury and fatality rate than occupations like logging, fishing, and steel working, for example. They and others argue that police academies should put less emphasis on safety (against other priorities like conduct toward suspects), that police should be less trigger-happy, and that statistics about violence against police receive too much attention.

Their arguments are wrong because they ignore the counterfactual: cops are relatively safer because they are taught to be safety-conscious. Just as important, these arguments fail to consider how the dangers of policing are unique. Loggers and steel workers take safety precautions, of course, but the injuries in those industries are mostly the product of accidents, not of human intention. In policing, by contrast, a significant subset of injuries and deaths are the result of choices by the people whom police are responsible for managing or apprehending.

The rising prevalence of officer injuries and deaths augurs poorly for efforts to curtail the national violent crime spike. Even if criminals don’t feel more emboldened to attack cops, rising violence against police may be a self-reinforcing phenomenon. The more dangerous policing is, the fewer there will be who want to do the job—or do it well. And that, in turn, will lead to more violent crime.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images