Resilience has long been a disaster-preparedness buzzword. How quickly and well can a region bounce back from a hurricane, earthquake, or terror attack? The answer is always a mix of where you started from when disaster hit, what your recovery policies are, and luck. The Covid-19 pandemic has been the ultimate test of America’s vastly disparate levels of resilience. From New York to Florida, from Illinois to North Carolina, state and local governments began, in March 2020, similarly, by shutting their economies down. By April, though, their governments and private sectors were taking radically different approaches, resulting in radically disparate outcomes. We can now draw preliminary conclusions about which of America’s most populous states are emerging strongly, relatively speaking, out of the pandemic—and which, nearly three years on, are struggling to recover their losses, let alone thrive.

Americans have an option that citizens of smaller, more centrally governed nations don’t enjoy. In picking up from, say, Illinois, and heading to Texas, they can move to or visit what seems like a foreign country, without leaving the nation’s borders. Pre-pandemic, the fortunes of nine states—Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas, on one side, and Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, on the other—had already sharply diverged. (This analysis leaves out California, which, twice as big as any state save Texas and with governance and political styles often at variance with the rest of the country, and even varied within its borders, is more like a nation of its own.) Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas began the new century with a collective population of 53.3 million people; by 2020, they had 72.5 million people, or nearly 36 percent growth. Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, by contrast, started out in 2000 with 65 million people, and had 66.4 million in 2020, just 2 percent collective growth. Thanks to low taxes and a generally lower cost of living, air-conditioned warm weather, and loose regulations, particularly on single-family home development in suburbs and exurbs, the new South was eclipsing the postindustrial North.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

This imbalance has created new political and economic power for the South. In 2000, the four southern Sunbelt states made up 19 percent of the nation’s population; today, it’s 22 percent. The northern industrial states, back then, claimed 23 percent of the U.S. population; now, it’s 20 percent. People followed the jobs, and vice versa. In 2000, the four powerhouse southern states had 20.6 million private-sector jobs; by the eve of the pandemic, in 2019, they could boast 26.4 million, a 28.6 percent rise. The nine northern states increased their private jobs total just 5.5 percent over that period, from 26.2 million to 27.6 million, watching the four southern states surpass them in employment. Further, though Pennsylvania grew at a relatively healthy pace, Michigan and Ohio actually lost employment, and Illinois was basically flat. New York State expanded during these two decades thanks to New York City, which grew its private-sector jobs a robust 28 percent.

Living in the South, pre-pandemic, retained some disadvantages—notably, lower income and life expectancy, on average. (These disadvantages were not universal; in 2019, Florida and Texas residents had higher life expectancies than people in Michigan and Ohio, for example.) But for Americans seeking fast-charging opportunity, without a sky-high cost of living, Florida and Georgia proved better bets than Illinois and Michigan.

As Covid-19 struck America, governors, whether Democrat or Republican, initially followed the Trump administration’s public-health advice to break off human physical contact and, thus, turn off much of the economy. “Effective at 8 PM on Sunday, March 22, all nonessential businesses statewide will be closed,” New York’s then-governor, Democrat Andrew M. Cuomo, decreed. Down in Florida, the response from Republican governor Ron DeSantis was the same. “All persons in Florida shall limit their movements and personal interactions outside of their home to only those necessary to obtain or provide essential services,” DeSantis ruled in early April.

Beyond its devastating impact on human life, Covid-19 was also a jobs crisis. As offices, restaurants, theaters, and construction sites closed from coast to coast, 19.4 million Americans had lost their private-sector jobs by late April. With the unemployment rate blasting from 3.5 percent to 14.7 percent within just days, this abrupt mass layoff was incomparable with any other sudden unemployment spike in history, even the Great Depression. Notwithstanding trillions of dollars in aid from President Donald Trump and the Democratic Congress to replace (and even surpass) unemployed workers’ lost income, the goal, from the perspective not just of ending the unsustainable federal largesse but also of protecting mental health and social cohesion, had to be to get people back to their normal routines, including work, as fast as possible.

Some governors, however, realized this far sooner than others, as they began to weigh the uncertain benefits of an economy-wide shutdown against the mounting costs. By late spring, state responses had separated. In New York, Cuomo wasn’t even considering opening most businesses. He wouldn’t announce a reopening plan until early May. Even then, reopening was plodding and inconsistent. Restaurants in New York City, for example, would remain in the months-away “phase four” of Cuomo’s four-phase, stop-start-and-stop-again plan, never mind entertainment venues, such as theaters, which stayed shuttered for more than a year. Even when New York City restaurants partly reopened in the summer, they shut down again over much of the long winter into 2021.

“Vigorous economies are helping the southern states close a drawback of working in the South: lower wages.”

In Florida, DeSantis began opening restaurants in early May 2020. By September, he had ditched all remaining Covid restrictions on business. “You can’t say ‘no’ after six months and just have people twisting in the wind,” he said. Broadly speaking, northern industrial states followed the Cuomo playbook, with partial closures persisting well into 2021. Southeastern states followed DeSantis, with partial indoor dining and other congregate activities going again by late spring 2020, and full activities more or less resumed by that fall.

The effects of the two approaches are clear in the jobs numbers. By February 2022, the United States had finally clawed back its lost Covid jobs. But Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas hadn’t just recovered; they were excelling. First, they beat the country’s recovery by nearly a year, gaining back their pre-Covid job totals by the summer of 2021. This early start enabled these states to gain economic strength, even as much of the country lagged. As of October 2022, the nation had just 1.8 percent more private-sector jobs than in October 2019. Yet Florida had 6.8 percent more jobs, Texas 6.7 percent more, North Carolina 6.1 percent, and Georgia 5.2 percent.

Big states that were slower to reopen are still suffering employment stagnation, even more than a year after ending restrictions. Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania are all missing between 0.6 percent and 1.8 percent of their pre-Covid jobs. But New York State, with among the nation’s strictest lockdowns, remains the worst performer. The state is still down 2.8 percent of its 2019 jobs, or 228,400 positions. New York City, particularly, has struggled. Quick to recover after the tech bubble burst and after 9/11 and even after the 2008 financial crisis, the city is missing 2.4 percent, or 100,100, of its pre-Covid positions. This experiment shows that states can’t just pause and restart their economies at will, as Cuomo and his peers tried to do. “Paused” jobs become lost jobs, long after extraordinary government aid for the unemployed has expired.

Liberal economists might retort that southern states are creating low-quality jobs. But they have seen income gains at a faster rate than the rest of the nation. In the U.S. as a whole, average weekly earnings are up 15.7 percent compared with the fall of 2019, as employers have had to raise pay both to lure workers back from home after the government’s generous pandemic unemployment-benefits program and to compensate them for rising inflation. Three of the four fast-reopening big southern states have outperformed this national average. This disparity is a function of supply and demand. States that got back to some normalcy fast needed more workers, rapidly. In Florida, wages are up 17.8 percent, in Texas, 18.8 percent, and in North Carolina, 20.8 percent. (In Georgia, they’ve risen at the national average.) In New York State, wages are behind the national average, with 15.3 percent growth; in New York City, they’re up just 13.6 percent.

Vigorous economies, then, are helping the southern states to close one of the historical drawbacks of working in the South: lower wages. In 2019, New York State had an average wage of $1,060 weekly, 9.1 percent above the national average. Today, its average wage is 8.8 percent above the national average, losing ground relative to the rest of the country. In 2019, Florida’s average wage was a full 10 percent below the national average; today, it’s just 8 percent under the national average, meaning that it—as well as its similarly situated peers—is gaining ground.

If you’re going to have a long economic shutdown, then you’d better be able to contain the noneconomic fallout. Despite their long-term loss of population and jobs share, northern states such as New York theoretically started the pandemic in far stronger positions to withstand lockdowns’ social side effects—which include rising violent crime and learning loss—than did Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina. New York and its industrial-state peers, after all, spend far more tax dollars per capita than southern states. New York State’s budget is more than twice that of Florida’s, despite a similar population size. Northern states also have legacies of big, activist government and progressive values favoring government responsibility for both public education and public safety.

Yet these states utterly fell apart, as the statistics convey. In 2020, the U.S. was hammered with the largest one-year rise in the homicide level ever, according to the Centers for Disease Control—a shocking 30 percent jump. Yet the murder rampage wasn’t evenly distributed throughout the country. In Florida, homicides rose by 16.4 percent, exactly meeting the national average of 7.8 per 100,000 people. In Georgia, they went up 30 percent, in line with the national average increase, to 10.5 per 100,000; similarly, in Texas, they rose 28.8 percent. In North Carolina, they increased 22.9 percent. There’s nothing to be proud of in these numbers, as other Western countries didn’t see a similar jump in murders. But New York’s kill surge, encouraged by 2019 changes to cash bail laws for criminal suspects as well as a general pullback in policing that resulted in many more violent suspects on the streets, far exceeded the nation’s. Statewide, murders rose 46.9 percent, to 4.7 per 100,000. Similarly, in Ohio, they went up 37.8 percent, in Illinois, 38.3 percent, in Pennsylvania, 39.3 percent, and in Michigan, 33.8 percent.

As with wages, liberal observers will argue that in raw numbers, northeastern states remain safer from deadly violence than southern ones. In 2020, Florida’s murder rate was 66 percent higher than New York State’s, and Georgia’s 23.5 percent higher than Pennsylvania’s. Yet this rejoinder isn’t monolithically correct. Illinois’ murder rate, at 11.2 per 100,000, is 47.4 percent higher than Texas’s. Michigan’s murder rate is higher than Florida’s, and North Carolina’s is on par with Pennsylvania’s. Furthermore, most of the murder explosion has been in big cities—in both the South and the North. Atlanta saw killings soar 58.6 percent, and they rose 42 percent in Houston. (In Miami, they increased “only” 12.9 percent.) But New York City’s murder rate blasted upward 46.7 percent in 2020, with comparably alarming increases in Philadelphia and Chicago.

Gotham’s new crime problem is particularly shocking. The city began the pandemic with a far lower murder rate than most urban areas—just 3.6 per 100,000. Indeed, the murder rate hit record lows between 2017 and 2019, an average of 302 yearly. For this, credit should go to city and state voters, who, over the previous 30 years, had set a low and ever-decreasing murder rate as a top public goal, and held several governors and (especially) mayors accountable for achieving it. A hyper-dense city like New York does not function well with a high homicide rate.

Residents of Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas have historically put up with far higher murder rates in their cities in part because of the greater sprawl of both urban and suburban populations. Mobile affluent and middle-class southerners, whether they live in or outside of cities, believe that they can more easily separate themselves from elevated-crime neighborhoods and can protect themselves through gated communities and (whether successfully or not) guns. It makes zero sense for New York, which long prided itself on its lowest-in-the-urban-nation murder rate, to give up much of those gains essentially overnight, using the excuse that other cities remain more dangerous. New Yorkers should be acutely concerned about their city’s abrupt reversal.

Successful dense cities have a far lower tolerance for lower-level disorder, too, than do more spread-out ones. Northern industrial cities hardly have a monopoly on the massive increase in drug use and antisocial behavior that has occurred over the past decades and, in particular, since the pandemic. But Miamians can protect themselves from open-air drug use by taking refuge in their cars. New Yorkers depend on public transportation and must now wait on platforms and ride on trains with people openly shooting up or smoking crack. Similarly, people with options who freely choose to live in dense, multifamily city apartment buildings do so because they have confidence that their government will enforce a basic code of communal behavior—from policing open-air drug use to confining the psychotically mentally ill—and not, say, allow dangerous vagrants to menace park-goers. If the government refuses to enforce such standards, people will increasingly move to enclosed communities, where private-sector managers will enforce them.

Covid shutdowns, with schools closed for in-person instruction, were accompanied by heavy learning loss and mounting teenage disorder and violence. Here, too, states took wildly divergent paths after their first closures. Florida, Georgia, and Texas restored in-person education in the summer and fall of 2020; North Carolina followed in the spring of 2021. In northern industrial states, however, large urban school districts in New York City, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Chicago stayed largely shut to consistent in-person learning for nearly 18 months. (These dissimilarities were not universal, with sporadic and exceptional shutdowns in the south and faster reopenings in some smaller districts in the north, but they broadly held.)

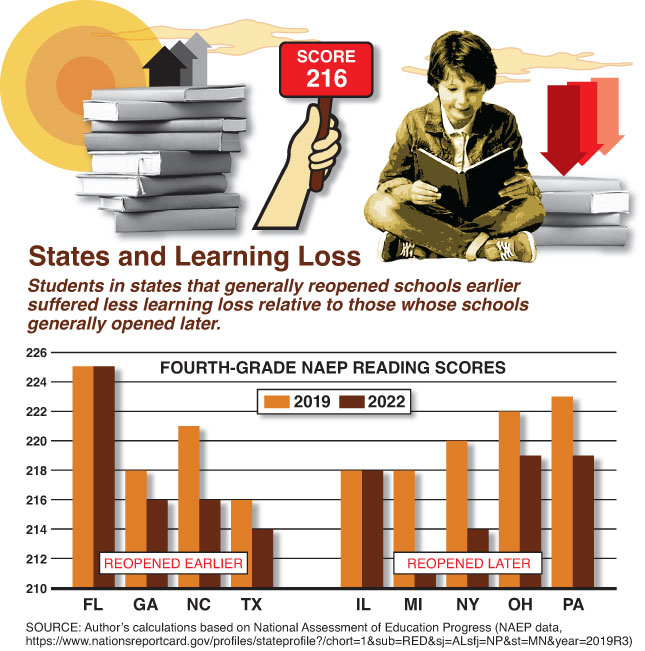

The grim consequences are reflected in test scores, if not perfectly consistently. Nationwide, fourth-grade students lost three points on their reading tests in 2022, compared with 2019, with the average score dropping from 219 to 216. North Carolina and Florida schoolchildren kept up with their 2019 scores, and Texas and Georgia students lost two points, beating the national average. New York and Michigan students lost six points on statewide tests. Pennsylvania students lost four, and Ohio students lost the national average of three. (The only outlier here was Illinois, where student scores were flat.)

These relative gains for fast-reopening southern states are particularly noteworthy because, unlike with some measures of well-being, such as average wages or (for the most part) statewide life expectancy, the southern states didn’t start off the pandemic with an educational disadvantage. In 2019, Florida and North Carolina actually bested nationwide reading scores, with Florida outperforming New York, and Georgia was close to the national average; only Texas was behind. Now, though, Texas meets the national average, and a preexisting chasm between Florida and low-performing New York is widening. Despite huge differences in education spending—$25,520 per student in New York, compared with Florida’s $9,337—Florida’s reading score of 225 is now 11 points above New York’s score; three years ago, the gap was only five points.

There’s no question, then, that reopening earlier came with clear benefits: faster recoveries and bigger job gains, smaller increases in homicides, and better—or, as with the homicide surge, at least not as bad—educational outcomes. But what were the costs, if any, in terms of illness and death from Covid?

Definitive conclusions aren’t there. Cumulatively, New York State and Florida have remarkably similar Covid-19 overall death rates: New York’s 394 per 100,000 residents to Florida’s 386. New York City’s Covid death rate, at 513 per 100,000, is the highest in the nation, and likely the highest in the developed world. But Miami isn’t far behind, with a death rate of 458 per 100,000. On an age-adjusted measure, Florida’s numbers look considerably better—299 deaths per 100,000 to New York State’s 370—or, more accurately, less awful.

Among other states with vastly different reopening schedules and policies, again no clear pattern emerges, save for Texas’s high age-adjusted death rate, at 412. Michigan’s age-adjusted death rate is 333, according to the Bioinformatics Research Group, North Carolina’s 308, Pennsylvania’s 342, Georgia’s 371, and Ohio’s 380.

“New York State and Florida have similar Covid-19 death rates: New York’s 394 per 100,000 residents to Florida’s 386.”

A risk-averse person might argue that, by reopening too early, southeastern states failed to heed the Northeast’s early-wave warnings and thus allowed preventable Covid deaths. Indeed, New York’s Covid fatalities peaked in April 2020, with a horrific toll of 969 deaths on one mid-April day alone, mostly in New York City; Michigan’s fatality numbers peaked the same month. In Illinois and Pennsylvania, despite widespread school closures and strict lockdown rules on restaurants and other venues, deaths didn’t peak until months later, in December 2020 and January 2021, respectively. Likewise, deaths hit their highs in Texas and North Carolina in the same later period, the winter of 2020 into 2021, despite different rules and weather conditions. And in Florida and Georgia, deaths didn’t hit their worst until September 2021, months after vaccines were broadly available, a full year after those two states’ full reopening.

A closer look at Florida and New York shows how hard it is to draw firm lessons. In Florida, it’s true that, during DeSantis’s reopening of the economy in late spring and summer 2020, Covid deaths rose consistently, even as they steadily fell in New York from their spring peak. Between July and October 2020, 1,704 New York State residents died, most of them in the city; that same summer in Florida, 13,283 people died, seemingly indicating a policy failure.

Yet it’s not so clear-cut. Between March and June 2020, 31,788 New Yorkers had died, and “only” 3,283 Floridians had died. In other words, Florida’s short-lived spring lockdown may have only delayed the state from confronting the deadly wave that New York had already endured. By the winter of 2020–21, daily Covid deaths in Florida were similar to those in New York. Between November and March of that season, 16,025 New Yorkers and 16,288 Floridians died from Covid, against the backdrop of roughly similar state populations and despite enormously different rules governing economic activity, with Florida entirely reopened and New York City, at least, still significantly closed under state decree—with no indoor dining, for instance. New York State’s death toll remained high that first full Covid winter, moreover, even though some of the most vulnerable people in the city had already succumbed during the early 2020 wave.

No governor made perfect decisions in an ever-changing disease environment. But we’ve all gotten either to the same death toll, in the end, or to dissimilar death tolls among different states, with no clear explanation as to why.

With more than 1 million Americans dead from Covid-19, it would be crass to say that any state is a winner. But Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas have shown themselves to be far more disaster-resilient than their big northern peers. For most large northern industrial states, Covid-19 accelerated a pre-2020 trend: population and jobs have shifted from north to south for decades.

Now, as the nation potentially faces a recession, states such as Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania would effectively enter it before recovering fully from a previous recession—still missing, as they are, so many pre-Covid jobs. New York, in particular, with so much to lose before the pandemic in terms of accumulated success in jobs growth and public safety in New York City, now has the most lost ground, post-pandemic, to make up.

Top Photo: Reopening earlier, Florida’s economy has surged. (OCTAVIO JONES/GETTY IMAGES)