In June 2021, videos of an incensed middle-aged white man getting dragged out of a Loudoun County Public Schools building in handcuffs, lips bleeding and belly exposed, played on repeat in the national media. Forty-eight-year-old Scott Smith, a Leesburg native, had attended the meeting, alongside hundreds of other parents, to protest the adoption of a new “transgender-affirming” policy proposal in the Northern Virginia school district. His arrest came to symbolize the angry, parent-led school board revolts about radical race and gender curricula sweeping the nation, though journalists typically told the story from the perspective of teachers and school administrators, not the mothers and fathers opposing them. “School board meetings, usually one of the most mundane examples of local democracy in action, have exploded with vitriol across the country in recent months,” NPR reported gravely. “School leaders are scared.”

Smith, a plumber, was the perfect foil for the media narrative about the grassroots parents’ movement. The conventional wisdom among elites—embraced by mainstream journalists, teachers’ unions, and Democratic politicians—held that bigotry and white rage drove the parental protests. “A white parent shouting at a school-board meeting because they don’t want their child learning the truth about racial inequality isn’t as blatant as the violence carried out by the Klan,” Slate’s Julia Craven complained. “But it is motivated by the same desire to protect whiteness, its stature, and the privilege it bestows.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

But Smith was no crazed white supremacist. He leaned conservative, but he and his wife were “gay- and lesbian-friendly” and “didn’t really follow politics until the last few years,” he told the Daily Wire in October. His fury at the June school board meeting was personal: on May 28, his 15-year-old daughter had been raped in a girls’ bathroom at the school by a boy who entered it wearing a dress. School officials assured parents that the allegations—which included two counts of forcible sodomy, one count of anal sodomy, and one count of forcible fellatio, and were corroborated by evidence from a rape kit—would be handled “internally.” What that meant was that the offender was moved to a different school, where he proceeded to assault another girl.

That was the context surrounding Smith’s appearance at the June school board meeting. To Smith’s dismay, the same administrators who had buried his daughter’s assault were pressing for a “rights of transgender and gender-expansive students” policy that would mandate access to school bathrooms based on “gender identity,” not biological sex. And when the bathroom rape was raised at the meeting, the Loudoun County Public Schools (LCPS) superintendent rubbed salt on Smith’s wound: “We have no records of any assaults occurring in our restrooms,” he insisted, waving away the allegation as a “red herring.” “We’ve heard it several times tonight from our public speakers, but the predator transgender student or person simply does not exist.”

In a horrendous inversion of justice, Smith wound up prosecuted as a criminal himself. When, in a moment of emotion, he verbally berated an activist in the crowd—a woman who had approached him during the meeting, saying that she was going to “ruin your business on social media” as retribution for his allegations about his daughter’s assault—he was arrested and banned from the school board building. (Police had earlier detained Smith for making a scene at the school the day that his daughter was raped; when he yelled at the principal for insisting on handling the assault in-house, six cop cars arrived to remove him from school premises.) Soon after, the county’s top prosecutor—a George Soros–funded district attorney with close ties to the progressives on the Loudoun County school board—showed up in court to try to put Smith behind bars for his misdemeanor “disorderly conduct” charge. It was unprecedented. “It is incredibly unusual for a disorderly conduct case to even go forward,” Smith’s attorney told the Daily Wire. “The idea that they would actually be seeking jail time, I’d guess in my 15 years the number of times I’ve seen that happen would be zero.”

Smith’s story may not have gotten attention if it weren’t for the national political environment. School administrators and their allies in local political bureaucracies were used to getting their way. Terry McAuliffe’s now-infamous remark during a 2021 Virginia gubernatorial debate—“I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach”—put it bluntly. Parents weren’t supposed to get involved; it wasn’t their place. The shock-and-awe campaign against Smith was a warning: don’t get in our way—or else.

Since its inception at the turn of the twentieth century, the progressive movement has seen the public school system as a potent tool for its political ambitions. Writing in 1930, progressive theorist John Dewey derided the pedagogy of his day as narrow-minded and visionless, arguing that “the traditional schools have almost wholly evaded consideration of the social potentialities of education.” But that was “no reason why progressive schools should continue the evasion,” he continued. Instead, he wrote in a subsequent essay, schools should “take an active part in directing social change and share in the construction of a new social order”; progressives should “make the schools their ally,” encouraging “the youth who go forth from the schools to take part in the great work of construction and organization that will have to be done.”

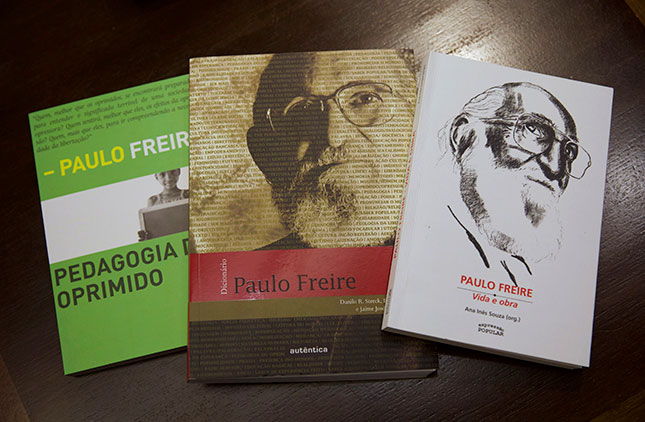

That activist orientation toward education—in which educators mold students into “agents of change”—radicalized with the rise of the neo-Marxist “critical pedagogy” movement in the late 1960s. Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), largely credited as critical pedagogy’s founding document, called for “a pedagogy which must be forged with, not for, the oppressed,” making “oppression and its causes objects of reflection by the oppressed.” Only then, Freire wrote, would beleaguered subjects be capable of “their necessary engagement in the struggle for their liberation.” Moving beyond Dewey’s reformism, Freire saw education as a way to propagate a revolutionary consciousness—a “process of permanent liberation,” through which “the culture of domination is culturally confronted . . . through the change in the way the oppressed perceive the world of oppression” and “the expulsion of the myths created and developed in the old order, which like specters haunt the new structure emerging from the revolutionary transformation.” In other words: critical pedagogy seeks the radical delegitimization of existing institutions and mores, encouraging students to be actively hostile toward everything about the society that they inherit.

“In a school in a suburb of Portland, Oregon, eight- and nine-year-olds were shown videos telling them that they were ‘racist.’”

Freire’s ideas now pervade American education. “Since the publication of the English edition in 1970, Pedagogy of the Oppressed has achieved near-iconic status in America’s teacher-training programs,” Sol Stern wrote in a 2009 City Journal essay. “In 2003, David Steiner and Susan Rozen published a study examining the curricula of 16 schools of education—14 of them among the top-ranked institutions in the country, according to U.S. News & World Report—and found that Pedagogy of the Oppressed was one of the most frequently assigned texts in their philosophy of education courses.”

The results are visible from graduate schools to kindergarten classrooms. As the reporting of Christopher F. Rufo for City Journal has documented, examples like these abound: in California, the Board of Education’s proposed Ethnic Studies Curriculum included lesson plans encouraging students to chant to the Aztec god of human sacrifice, asking him to grant them the power to be “warriors” for “social justice.” Third-graders in the state were told that they lived in a “dominant culture” of “white, middle class, cisgender, educated, able-bodied, Christian, English speakers” and told to rank themselves according to their “power and privilege.” In a school in a suburb of Portland, Oregon, eight- and nine-year-olds were subjected to videos telling them that “of course” they were “racist” and that “the idea that somehow this blanket of ideas has fallen on everyone’s head except for yours is magical thinking and it’s useless.” Rather than “affirm the status quo of certain bodies being allowed resources, access, opportunities, and other bodies being literally killed,” the students were instructed to embrace “revolution,” “resistance,” and “liberation.”

Even in the deepest-red areas of the country, school boards often fall under the control of Freirites. In Frederick County, a northern Maryland area that has gone Republican in every presidential election but two since 1940, the school district formed a “Racial Equity Committee,” charged with “identifying discrimination or harassment, raising awareness of implicit bias, and eliminating or mitigating racial inequity or its effects across the entire school system.” The committee immediately set about attempting to push the school to teach American history “through an equity lens.” In Lansing, Kansas—an 11,000-person city in a county that has voted Republican by double digits in every presidential election since 2000—parents objecting to the implementation of critical race theory–based training for faculty and staff found themselves derided as right-wing extremists by local school officials. A left-wing activist campaign even led to a CRT-critical school board candidate, a 62-year-old, getting fired from her job of 42 years.

For the past half-century, the culture war has been less a battle of equals than a story of David and Goliath. From same-sex marriage to school prayer, the appetite for social transformation unleashed in the 1960s has grown in power with every victory. “History” was supposed to move in only one direction, with the advocates of liberation confident that they were on the right side.

So the fierceness of the recent backlash to CRT and gender ideology in schools took the public education bureaucracy by surprise. The parental uprisings were the bill coming due for the activist agenda that had swept through public education in recent years. As the Black Lives Matter movement marched through American life in 2020, school boards—already dominated by progressives—redoubled their commitments to the most extreme pedagogical concepts involving race and gender, without pausing to consult parents. In response, parents across the country began emerging as a formidable political force. Moms and dads suddenly were signing petitions, holding protests, and demanding answers from a school system grown accustomed to operating without parental scrutiny. In lieu of bake sales and library drives, parents were pulling together to lobby for curricular change.

Some, like Tiffany Justice, even ran for school board seats themselves. Justice, a mother of four, originally won a seat on Florida’s Indian River County school board in 2016, well before the current school battles. Justice’s struggle against the education system was initially just about basic quality-of-life issues. But Justice soon “got a real look at what happens” in local school bureaucracies: “Oftentimes the people who worked within the district or ran the school board had all these relationships that kept them from doing what was best for kids. I would go into the executive bargaining sessions, and the teachers’ union would bargain for the teachers. The district would bargain for the district system. Who was bargaining for the parents and the kids?”

In January 2021, Justice cofounded Moms for Liberty, with Tina Descovich, another mother serving on a school board in a neighboring county. The 501(c)4 “started with two chapters—one in my county, one in Tina’s county,” Justice says. “Within three weeks, we had a call from Nassau, New York—it was a Long Island mom who called us and said, ‘I want to start a Moms for Liberty chapter.’ ” From there, the movement spread. Now, Justice says, “we have over 200 chapters in 37 states.”

For decades, American public education had continued to press left, largely without organized opposition. But in 2020, something broke. That year, “two simultaneous phenomena occurred,” Rufo says. “First, you had the pandemic, which shut down schools and made classrooms virtual, so parents could have a really close look at what was being transmitted to their kids.” And second, he continues, “after the death of George Floyd, you had this universal spasm through all of our institutions, which were tripping over themselves trying to adopt the left-wing racial ideology. A lot of these more radical educators—whether they’re in the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion departments of K–12 public schools, or actually in the classroom—saw that as their greatest opportunity in decades to start promoting those left-wing racialist ideologies throughout the education system.” Parents “hit the panic button,” says Rufo.

Justice agrees. “During Covid, we saw an expert class that failed us,” she says. “It’s very hard when you’re a parent, and you’ve chosen a direction for your child’s education, to admit that what you’ve chosen isn’t working. But parents, all of a sudden, saw all of these people whom they had trusted failing their kids. And then they were emboldened to ask more questions.”

The parents’ movement had another powerful tool at its disposal: social media. Videos of parents giving impassioned speeches at school board meetings routinely went viral last year. One Virginia mother, Stacy Langton, was banned from her district’s school library after she was shown, in a widely circulated video, confronting the Fairfax County school board over the presence of the sexually explicit graphic novel Gender Queer on the library’s shelves. But the district’s harsh crackdown against Langton only served to make her—and the movement she represented—more sympathetic. “The only weapon I have at my disposal, to try to force them to do the right thing, is to continue to apply the pressure publicly,” Langton tells me. “And that’s the thing I think that parents need to take from my example and the example of other parents who have gone to these school board meetings. There’s so much value in simply showing up and saying your piece—because look at what’s happened since last September. Who would have thought, when I went there on September 23, that we would be having a national conversation about gender ideology in schools six or eight months later?”

These days, Langton says, “parents randomly reach out to me on Twitter. I get so many comments and remarks from parents all over the country that they’re more awake about this issue now than they were even last fall.” People regularly send her videos of other parents who brought Gender Queer to their school board meetings. “Other parents are taking the baton and running with it,” Langton observes, “and they have the courage now to speak up.”

At least 17 states have passed restrictions on the teaching of CRT-based concepts in public schools; others are expected to follow suit this legislative session. Some states, including Florida, have also passed bills cracking down on the teaching of radical sexual and gender ideology in the classroom. School board recalls hit an all-time high in 2021, according to Ballotpedia. That dissatisfaction has even reached deep-blue areas like San Francisco, where voters recalled three school board members by landslide margins in February.

The institutional conservative world has also coalesced around the parents’ agenda: think tanks (including City Journal’s publisher, the Manhattan Institute) are producing model legislation for CRT bans, sending scholars to testify before state legislatures on the topic, and committing resources to bridging the gap between the Beltway and the grassroots. In December 2021, Rufo helped the Heritage Foundation produce a mission statement of sorts for the parents’ movement, signed by numerous heavy-hitters in the world of conservative education policy. “The entire movement has shifted in the last two years,” says Rufo. “Critical race theory provides us with what I believe is the proof of concept and the political model for how to fight these fights. At the beginning, when I was first reporting on CRT and working on the activism side of the issue, a lot of the more establishment political and intellectual figures were hesitant. But if you fast-forward a year, pretty much the entire movement is on board.”

At the legislative level, rising Republican stars like Florida governor Ron DeSantis have cut their teeth on the school issue. DeSantis broke through with conservatives during the pandemic, when he made the difficult decision to force school districts to reopen, over the objections of unions, many health officials, and the national media. As the pandemic subsided, and the debates over curricular issues emerged, the governor passed an aggressive slate of bills addressing everything from CRT and gender ideology to viewpoint diversity, civics education, and parental rights.

“In part what elevated it was parents bringing this forward, saying, ‘this was in my child’s textbook,’ or ‘my child’s teacher wrote these odd things on the whiteboard,’ ” an official in DeSantis’s office explains. “We started asking about what avenues we had to investigate this because first off, a lot of this content, just historically, it’s fiction. Second, it’s a very indoctrinating—kind of brainwashing—type of curriculum. And third, it’s taking away time from the curriculum standards that schools are required to teach.” Complaint after complaint came in, the official says—“from districts, from different schools, and from teachers themselves, saying, ‘I’m not comfortable teaching this. I know it’s fiction. I know it’s not accurate. Why am I being told to teach this?’ ”

Other states have followed suit. In Texas, Governor Greg Abbott signed laws aimed at combating CRT and renewing civics education in public classrooms, and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick has made a ban on instruction surrounding sexual and gender ideology—akin to Florida’s hotly debated Parental Rights in Education Bill—a “top priority” for the next legislative session. States such as Alabama have already passed laws aimed at combating gender ideology in public schools. South Carolina governor Henry McMaster launched “a comprehensive investigation into the presence of obscene and pornographic materials in public schools in South Carolina.” And Republicans like Glenn Youngkin have run and won on the curriculum issue. In 2021, the gubernatorial candidate staged an upset victory in typically blue Virginia by tapping a reservoir of parental dissatisfaction, polling ahead of his Democratic opponent among parents of K–12 students by nearly 20 points in the lead-up to the election.

Public opinion appears firmly with the Right in these debates. Florida’s parental rights bill, dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law by critics, is favored by 16 points by registered voters nationwide. According to YouGov, Americans who have heard of CRT disagree that it “is something students should be exposed to in school” by 14 points.

But the education bureaucracy won’t go down without a fight. Smith’s story was only one of many examples—the parents’ movement has been widely denigrated in the media, decried by local and national politicians alike, and attacked by a constellation of powerful institutions. The National School Boards Association even asked the Biden administration in a letter to “examine appropriate enforceable actions” against school board protesters under the PATRIOT Act in September 2021. (An earlier draft of the letter requested that “the Army National Guard and its Military Police be deployed to certain school districts and related events where students and school personnel have been subjected to acts and threats of violence.”)

Some parents, like Rhode Island’s Nicole Solas, have been targeted by teachers’ unions. The stay-at-home mother is battling a lawsuit filed against her by the Rhode Island chapter of the National Education Association in response to open-records requests that she filed to learn more about the content of her children’s education. Particularly in blue states like Rhode Island, parents face an array of social and institutional pressures. “People send me screenshots of people bad-mouthing me online, in my town,” Solas tells me. “My town is extremely liberal and in a very liberal state. But I do have a lot of allies. You would never know it, because of the politics of the town. But people are really determined to get common-sense candidates in school board seats.”

“The battle for the classroom matters; it is a microcosm of questions at the root of our political divisions.”

Taking an incremental approach, parents like Solas and her many counterparts are reclaiming American schools. The battle for the classroom matters; it is a microcosm of first-principles questions at the root of our political divisions. Debates over education policy, traditionally organized around technocratic issues like public funding and school choice, have become a proxy for the nation’s broader cultural fissures—the teaching of American history, the meaning of gender, the rights of parents and families, and traditional American notions of “equality” versus a race-conscious vision of “equity.”

The Left’s treatment of the classroom debate is characterized by a fundamental antipathy to the traditional family. McAuliffe’s dismissal of the idea that parents should have a say in their children’s education has long been a feature of progressive political philosophy. Back in 2013, an MSNBC promotional video featured one of the network’s hosts denouncing “our kind of private idea that kids belong to their parents, or kids belong to their families.” In a 2021 op-ed for the Washington Post—titled “Parents Claim They Have the Right to Shape Their Kids’ School Curriculum. They Don’t”—two education-policy writers worried: “To turn over all decisions to parents . . . would risk inhibiting the ability of young people to think independently.” Speaking at a teachers’ conference earlier this year, Joe Biden declared: “They’re all our children. . . . They’re not somebody else’s children; they’re like yours when they’re in the classroom.”

The Right has a historic opportunity to position itself as the “parents’ party.” The parents’ movement is driven by the most powerful impulse of all: a desire to protect one’s children. As long as progressives are unwilling even to recognize the existence of a cultural problem in their approach to the classroom, they will continue to drive away the millions of working- and middle-class parents who may not think of themselves as conservative in the traditional sense but are repelled by college campus–style wokeness; indignant at critical race theory, gender ideology, and anti-Americanism in their children’s schools; and suspicious of the Left’s radically ambitious social-engineering schemes.

In this sense, the political earthquake in public education contains the seeds of national renewal. The art of self-government is no easy task; good citizenship must be taught. For most of our history, the education system was organized around teaching young Americans a love of justice, an understanding of the distinction between liberty and license, and a sense of patriotic duty. There’s no reason that this cannot be our future, too—across the country, mothers and fathers are demanding as much. We should listen.

Top Photo: A rally against the teaching of critical race theory in public schools (ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)