The memory that sticks out to Jim Murphy from the screwiest bank robbery in New York City’s history is not the slow drive down a dark road at JFK Airport, with a shotgun leveled inches from his head, or the scrum of onlookers hooting and hollering every time hostage-taker John Wojtowicz stood toe-to-toe with negotiators. It’s not the salacious details of Wojtowicz’s backstory—man robs bank to pay for his “wife’s” sex-change operation in attempt to woo him/her back—or the pop of Murphy’s revolver as he shot Sal Naturale during a struggle for control of Naturale’s shotgun. It isn’t the kiss on the cheek from the hostage he had just saved, or the night, a few years later, that he saw Lance Henriksen play a grim-faced caricature of him in Dog Day Afternoon, the Sidney Lumet film based on the 1972 robbery, while seated in a theater packed with an audibly pro–Al Pacino (playing “Sonny Wortzik,” the fictionalized version of Wojtowicz) and anti-Henriksen audience.

What Murphy remembers most is the shot he didn’t take. It’s the feeling of the trigger as he aimed his gun at Wojtowicz, the mastermind of the robbery. At that moment, Murphy had just shot Naturale in his torso. Another FBI agent had just disarmed Wojtowicz of his rifle. But Wojtowicz also had a pistol in his waistband. His hands were slowly moving down toward his waist. Murphy knew that Wojtowicz had the pistol and commanded him to “freeze,” to get his hands back up in the air; his trigger finger maintained the tension between mercy and retribution.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Fifty years later, seated at a diner in Fresh Meadows, Queens, Murphy says that he can still feel that tension, the great control he had at that moment—and when Wojtowicz eventually complied with his orders, the sensation of the trigger’s release. Had Murphy not released it—had the incalculable hours of training he received at the Bureau not kicked in—he could have shot two men that early morning instead of one. Wojtowicz “wasn’t at his gun yet. He was going for it. I could have shot him, and people would have said it was a justifiable shooting. I don’t think that’s the best way to behave. The instinct isn’t to kill somebody. The instinct is to stop the action,” Murphy noted.

“You can’t leave these things in the bad guys’ hands. And I use ‘bad guys’ for lack of a better term. We’re talking about a moment. I don’t think Sal was a bad guy. I don’t think there’s anyone in the world who’s a bad guy, you know? But he put himself in a very bad situation where the opposition can’t make that distinction,” said Murphy.

Both the robbery and Dog Day Afternoon brought Murphy stature and admiration within the Bureau, as he regularly gave talks to starstruck FBI agents about the eternal conflict between the facts of a case and its Hollywood portrayal. Outside the Bureau, he remained relatively anonymous—few people knew of his involvement in the robbery, save for friends and family. In both the film and in published reports about the event, he was known simply as “Murphy.”

Today, Murphy runs his own private investigation firm, which he’s done since he resigned from the Bureau in 1984. He looks the same as he did back then, save for more gray in his close-cropped hair. He still loves the Bureau and everyone he worked with there. He still wears collared shirts, ironed to perfection, still wears an expression that’s congenial yet discerning, still speaks in a gentle Queens accent. He is a man at peace with his life and the good and bad it has brought with it.

Murphy could have stayed at the Bureau and risen in the ranks. His last role was as assistant special agent in charge at the FBI’s Brooklyn-Queens Metropolitan Resident Agency. But he retired early to be closer with his family and take care of his younger son, who, at the time, had been diagnosed with cancer. He remains a man of deep Catholic faith. For the past 20 years, Murphy has served as a deacon for the Diocese of Rockville Centre. That evening, he would be presiding over a wake service for a family that had just lost a relative to suicide following a struggle with depression. “We’ve got to make some sense of it.”

As for Sal Naturale, the young man he shot, he feels sorrow for him. He wishes things could have been different. Naturale, in Murphy’s mind, was a lost soul, a person whose free will steered him wrong. But for Murphy, sorrow does not equate guilt. “I do feel bad about Sal. The kid never had an opportunity to live his life. That has nothing to do with guilt,” Murphy said. “He got up that morning not having any idea what was going to be happening so many hours later. He had no idea, nor did I, on where he was going to be that night.”

For Wojtowicz, the bank robbery was over a man who wanted to be a woman. Wojtowicz met Ernest Aron at St. Anthony’s feast in Soho in 1971. Tall, thin, and effete, Aron was dressed in semi-drag. Wojtowicz, a Vietnam veteran, was smaller, irascible—and promiscuous. He was also a married father of two who became involved in the Gay Activists Alliance under the alias “Littlejohn Basso,” the last name a nod to his mom’s maiden name, the first a reference to his microphallus.

“He was a Goldwater Republican who volunteered in the war in Vietnam to serve his country, came back home with his brain scrambled, and somehow in the Army he discovered he liked having gay sex,” said Randy Wicker, a reporter, author, and gay activist who knew Wojtowicz and Aron. Wojtowicz became infatuated with Aron, and, after a long courtship, they got “married” in an informal ceremony, with Aron in a flowing wedding gown and his male wedding party dressed as bridesmaids.

But Aron’s desire to transition to a woman caused friction in their relationship. Wojtowicz opposed the idea. During an argument, Aron had told him, “I want to have a sex change, or I want to die.” Aron became suicidal, and on his birthday on August 19, 1972, he overdosed on pills and was taken to King’s County Hospital, where he was committed to the psychiatric unit.

Heartbroken and determined to get Aron out of the hospital, Wojtowicz recruited Bobby Westenberg and Naturale, a 19-year-old from New Jersey with priors for grand larceny and drug possession, to help him rob a bank. After a few false starts at other banks in the city—in the 2013 documentary about him, The Dog, Wojtowicz recalled that they dropped a shotgun outside a Lower East Side bank, cutting that attempted robbery short, while Westenberg ran into a family friend at another bank in Howard Beach—they eventually settled on a Chase Manhattan Bank in Gravesend, Brooklyn.

“In contrast to today, bank robberies and hijackings were exceedingly common in the 1970s. ”

On August 22, 1972, at closing time, Naturale and Wojtowicz, armed with a colt revolver and carrying a .303 British rifle and a 12-gauge shotgun, both concealed inside a box, entered the bank. Westenberg was supposed to hand a typewritten note to the teller:

Instead, he got cold feet and fled the bank, abandoning his two accomplices with seven bank tellers, a branch manager, and an unarmed security guard.

Without Westenberg, Wojtowicz and Naturale proceeded with the robbery. Naturale, revolver in hand, approached the desk of Robert Barrett, the bank manager, and informed him that his bank was being held up. The excitable Wojtowicz, rifle now out of the box, jumped behind the teller’s counter and went through the drawers and carriages, separating real money from the decoy bills, telling bank employees that he had once worked in a bank himself and knew how these things went.

The bank tellers were instructed to keep answering phone calls and to act as though everything was fine. When Barrett got a call from a human resources officer at Chase Manhattan’s downtown office to discuss staffing, the officer, struck by Barrett’s unusual tone, asked if there was a problem. “Very much so and have a nice day,” said Barrett, before hanging up. Chase Manhattan notified the NYPD.

As it is today, New York City was then grappling with troubling crime numbers. Midway through 1972, 810 homicides had been committed in the city—a new record—along with 443 shootings, according to the New York Times. In comparison, in 2022, 559 shooting incidents had taken place in New York as of June 12, NYPD statistics show. The number of murders—185 during this time frame—thankfully hasn’t reached 1972 levels. But serious crimes have been rising in the city for several years now.

THERE IS NO REASON FOR ANYONE TOO [sic] BE INJURED OR KILLED. IT IS ALL UP TO YOU. THIS IS AN OFFER YOU CANT [sic] REFUSE

In contrast to today, bank robberies and hijackings were exceedingly common in the 1970s. Gotham saw 469 bank robberies in 1970–71 alone, the New York Times reported. Back then, these crimes—along with kidnappings and hostage negotiations, among other disruptions—informally fell under the auspices of the FBI’s Bank Robbery Squad. Working on nonviolent squads that handled, say, white-collar crimes, involved long hours stationed at desks or inside surveillance vans. The Bank Robbery Squad, by contrast, gave agents the chance to work the high-risk and dangerous cases that made them want to join the Bureau in the first place. “Some of the groups that we worked that were committing bank robberies were the BLA [Black Liberation Army], the Weather Underground, and the Westies. You had bank robberies where guys went in and claimed they had a bomb with them,” recalled Murphy.

Working for the Bank Robbery Squad meant being a jack-of-all-trades—sharpshooter, hostage negotiator, investigator, anything the situation might call for—at a time when bank robberies were a daily occurrence in New York. “You had to be prepared for meeting violence at the time of an arrest, and that was the adrenaline rush that we all sought and pursued, not for glory, but to get these guys and get them off the street,” said Kenneth Lovin, a former FBI Special Agent with the Bank Robbery Squad.

Skyjackings were another unofficial FBI specialty. It was “the golden age of hijacking,” observes Brendan Koerner, in The Skies Belong to Us. More than 130 U.S. airplanes were hijacked between 1968 and 1972. One such attempted takeover involved Richard Obergfell, an unemployed airline mechanic and lovesick New Jersey native. He had become infatuated with a woman in Italy, who was also his pen pal. He boarded a Chicago-bound TWA flight and, using a pistol he sneaked onboard with him, commandeered the plane, demanding that it be rerouted to Milan. As the Boeing 727 lacked the fuel capacity for a cross-Atlantic trip, Obergfell was flown back to LaGuardia and transported by car to JFK, where another jet awaited him and the air stewardess he had taken hostage.

The Bureau tried to de-escalate the situation, bringing in a Catholic priest and FBI negotiators to reason with Obergfell. Those tactics failed. When Lovin arrived at JFK, John Malone, assistant director in charge of the FBI’s New York Field Office, ordered him to stand behind a blast fence 175 yards away from the plane, armed with a Remington 760 rifle. When Obergfell was to make his way from the car toward the plane, Lovin had orders to take the shot—but only if he could avoid harming the stewardess. Lovin had scoped him for 15 minutes when Obergfell became distracted by a police car. “During his moment of excitability, he removed the gun for a matter of a few inches away from the girl’s head. And when he did that, I felt that even if I hit him and he pulled the trigger, she was in no danger. And that’s when I took my shot,” recalled Lovin. He shot Obergfell twice, sending him to the ground. The stewardess escaped unscathed. Obergfell died. The Federal Aviation Administration told the New York Times that it was the first fatal shooting of a hijacker in the United States.

“We tried to appeal to him and to de-escalate, and we wanted it to be resolved without any loss of life, period,” Lovin said. “But things don’t always work out that way.”

Murphy was in the FBI’s field office on East 69th Street when they got the call from the NYPD advising of the bank robbery in progress. By then, it was all over the media. NYPD and FBI snipers were already positioned on roofs. “Anyone else who had a right to carry a gun showed up,” noted Murphy.

Bob Kappstatter, then a reporter for the Daily News, managed to get Wojtowicz on the phone by calling the bank. “I asked him, ‘How you doing? Do you think you could kill all these people?’ And he says, ‘Yep, I could kill.’ So we’re off and running,” says Kappstatter.

Murphy arrived on the scene to find thousands of spectators watching the standoff from the tops of trucks and behind police barricades. By then, the bombshell had already dropped: Wojtowicz was robbing the bank to pay for Aron’s sex change. “You couldn’t think of a better angle while a story was happening. It came out of the blue, and people’s jaws were dropping,” said Kappstatter. Wojtowicz confessed to being a “homosexual,” something that also made headlines back then. Inside the bank, Wojtowicz told tellers that he didn’t plan to harm them—that the police had forced his hand to keep them as hostages.

By 8:00 PM, Dick Baker, special agent in charge at the FBI’s New York City office, took over hostage negotiations from the NYPD. Wojtowicz left the bank throughout the late afternoon and into the evening to speak with negotiators, each meeting causing a stir from the crowd. Wojtowicz, dressed in a T-shirt, offered to trade a hostage for Aron, who was still in Kings County Hospital. He asked for hamburgers to be delivered to the bank. Instead, pizza was dropped off at the front door, for which Wojtowicz paid by tossing $1,000 in cash in the air, FBI agents scrambling to pick up the bills. The hostage-takers never ate the pizza, fearing it was drugged. “Every time he did exit the bank, he’d have the community yelling and screaming and chanting in support of them,” said Murphy. Inside the bank, the atmosphere between the hostages and their captors was, surprisingly, festive. “We cried, we laughed and joked. We took it as it came,” one of the hostages told the New York Times.

Eventually, Aron was brought to the scene, per Wojtowicz’s request. But he refused to meet with Wojtowicz directly, fearing Wojtowicz’s “bad temper.” Instead, Aron was set up at a neighborhood barbershop, which had been converted into a makeshift police command center. Wojtowicz said that “he wanted to come out but he was afraid to, and that if he left, Sal would kill everybody,” according to Aron, in archival footage in The Dog.

Meantime, the police had cut off both the telephone lines and the air conditioning. Wojtowicz and Naturale were now overheated and hungry. Sure, the two men now had over $38,000 in cash and nearly $175,000 worth of traveler’s checks in their possession. But with that had come eight restless hostages and unrelenting, unflattering media coverage. They were trapped inside a bank, surrounded by a battalion of law enforcement and spectators who wanted to see things escalate to an explosive finale. (On two occasions, Wojtowicz fired his gun, once toward the rear of the bank upon hearing a “menacing” noise, another when he accidentally discharged his rifle after bumping it into a desk, nearly blowing off a foot.) What Wojtowicz didn’t have was Aron—or a clear escape plan.

After hours of negotiations, Baker and Wojtowicz reached an agreement. The two robbers would be taken with their hostages to JFK, where a plane would fly them to multiple destinations. At each stop, two hostages would be released, and when all the hostages were off the plane, Wojtowicz and Naturale would continue on to freedom, wherever that might be. Inside the bank, the robbers and their hostages brainstormed ideas on where they’d go—maybe Moscow, maybe Tel Aviv.

But how would the two robbers and their hostages get to the airport? There was talk of taking separate cars, one robber and a few hostages per car, to JFK. Ultimately, it was agreed that they would be transported in an airport limousine, with a sole FBI agent, who would be at the wheel. Baker presented four agents to Wojtowicz, having them stand in a line in front of the bank. Among the four were Thomas Sheer, a former Marine who would go on to serve as assistant director of the FBI from 1986 to 1987, and Jack Jansen, who stood over six feet and was built like a boulder. Wojtowicz looked them over and pointed at the least physically imposing of the four. “I’ll take him,” he said—meaning Murphy.

Wojtowicz went back into the bank. It dawned on Murphy that someone was going to die that night. It could be him. It could be one of the bad guys. God forbid it be one of the hostages. It was an unsettling feeling. Murphy turned to the crowd and looked for the priest he had seen earlier—the one who had tried to reason with Wojtowicz.

As the product of a Catholic education, from grammar school through St. John’s University, Murphy remained a man of faith. But he wasn’t living that faith the way he would have liked. If this was going to be it, he wanted to demonstrate remorse for any wrongs he had done. It would be a while before the airport limousine arrived. Murphy approached the priest. “I told him what was going to happen. I told him my concern was that there was a real possibility here that someone was going to die, someone was going to get shot, and it could be me. I asked him if he would hear my confession,” Murphy recalled. They walked along the tree-lined streets away from the crowd, and the priest listened to his confession. When they returned, Murphy felt at peace.

Then the limousine arrived.

The first challenge for Murphy was where to secrete his weapon, a Smith and Wesson model 15. An agent offered his ankle holster and weapon, but Wojtowicz would find it if he patted Murphy down. He settled on placing the gun underneath the gas and brake pedals, concealing it under the floor mat.

Murphy drove the airport limousine to the front of the bank. Wojtowicz ordered Murphy to walk to the back of the vehicle, in order to be frisked. Wojtowicz made a great show of the pat-down, slowing down his search when he reached Murphy’s groin. The spectators went bananas. Murphy felt humiliated. Murphy returned to the driver’s seat and placed his foot on the brake. Wojtowicz searched underneath the driver’s seat and other locations—but not beneath the pedals. When Wojtowicz went to get the hostages, Murphy put the gun in his belt, covering the grip with his tie.

Around 4:10 AM, Wojtowicz and Naturale exited the bank. Naturale had hostages huddled around him—a human shield. In the limo, three hostages were placed in the second row. Naturale sat in the middle of the third row, a hostage on either side. In the last row was Wojtowicz, sitting in the middle, also sandwiched between two hostages. There were now seven hostages left—a security guard had been released earlier in the standoff, and another hostage had been allowed to leave when everyone walked out of the bank. At 4:45 AM, Murphy and his passengers headed off to the airport. Baker was in the lead car in front of him. Behind him was a 20-car convoy of law-enforcement vehicles. It was a 25-minute drive to the airport.

Naturale was extremely nervous, Murphy saw. He held the shotgun at the back of Murphy’s head.

“Sal, do me a favor and put that up. My wife will be really disappointed if that goes off,” said Murphy.

“Don’t worry. It won’t fire,” replied Naturale.

“If we go over a bump and it accidentally discharges, it’s going to fire and I’m not going to be here anymore,” said Murphy. Naturale lowered the gun.

On the drive over, they exchanged small talk, putting both hostage-takers at ease. Wojtowicz was starving and wanted to stop and get hamburgers. That couldn’t happen, Murphy explained, but he would see if he could sort something out at the airport, maybe get them some food on the plane.

At JFK, Murphy turned onto a long, dark road that would take them to the satellite area where the plane would eventually be—the same area where Obergfell was shot. Naturale was now frightened. He again raised the gun to Murphy’s head.

Baker had already arrived in the satellite area. Murphy stopped the limousine and said he’d talk to Baker about getting them some food. Per prior agreement, a hostage would be released at the airport. It was supposed to be Barrett, but he refused. Instead, it was one of the women sitting behind Murphy, creating an opening between him and Naturale.

Baker and Murphy met halfway between the cars and devised their plan. When the airplane taxied into the satellite area, Baker would walk back to the limo’s right rear window, close to where Wojtowicz was sitting. With Baker in position, if Murphy thought he could take the shotgun from Naturale, he would ask Baker, “Will there be food on the plane for these people?” If Baker responded yes, it meant that he thought he could get the rifle from Wojtowicz, who had it resting on his lap. Their plan decided, Murphy returned to the limousine. Baker was looking into getting some food for them, he told the robbers.

It was another 20 minutes before the plane would arrive. Murphy slowly got himself in position, resting his right knee up on the seat. He had his right elbow on top of the seat, his handgun concealed in his right hand. They continued the small talk.

The plane taxied into the satellite area. The glare of the lights and the whine of the jet engines distressed Naturale even more. Baker casually walked back to the rear window. Murphy turned around, sensing Naturale’s unsteadiness.

“Will there be food on the plane for these people?” asked Murphy.

Baker looked at him. “Yes.”

Murphy swung in his seat. He grabbed Naturale’s shotgun with his left hand and pushed it up to the ceiling, raising his gun in his right hand while doing so. Naturale hung on to the shotgun with both hands. Murphy fired a shot, hitting Naturale in his chest. Naturale let go and collapsed in his seat. Baker pulled the rifle away from Wojtowicz.

The hostages opened the doors and streamed out. Murphy had his gun on Wojtowicz, whose hands were inching down. But Murphy didn’t shoot him. Wojtowicz stopped. The robbery, as sensational and unprecedented as it was, had reached a predictable end.

Murphy jumped over his seat. With Murphy’s hand on the back of his neck, Naturale let out one long exhale, flapping his lips, and then stopped breathing. He died on the way to the hospital. Later that evening, a hostage approached Murphy and asked if Naturale had died. “Yes,” he responded. “That’s too bad,” she said, kissing him on the cheek.

Murphy’s case was the third incident in 1971–72 in which hostage-takers were shot and killed by special agents from the Bank Robbery Squad. Lovin’s was the first.

The second was the hijacking of a Mohawk Airlines plane by Heinrich von George, a failed businessman and father of seven, who faced indictment for simultaneously drawing welfare and unemployment checks. Von George successfully hijacked the plane as it departed Albany, using what he claimed were a pistol and a bomb. The plane landed at Westchester County Airport, where he released all the passengers. After hours of negotiations, he received the $200,000 and two parachutes that he had demanded.

The plane departed for Pittsfield, Massachusetts, diverted midair to Poughkeepsie, New York, per von George’s orders, and landed at Dutchess County Airport, where a car waited on the runway for him and his hostage, a stewardess. As von George entered the car, FBI agents charged. They had followed von George’s plane in one of their own, flying with no lights. One of those agents was the massive Jack Jansen, who, months later, would be rejected by Wojtowicz as a driver to JFK. Jansen jumped in, pulling the woman away from von George. He had his shotgun aimed at von George and yelled “freeze.” Von George raised his gun toward Jansen and fired. Jansen returned fire, shooting von George in the throat at point-blank range. He died, facedown on the tarmac. Von George’s gun turned out to be a starter pistol. The bomb was two canteens filled with water and wrapped in a red blanket.

Three failed crimes committed by three failed men, each a victim of a thousand self-perceived indignities. They all shared the same delusion: that the bounty they would steal would finally bring them the life owed to them, the people they desired, the respect they desperately needed. Their strategies were, at best, half-baked. The crimes themselves would be beset by delays, intense negotiations that dragged on for hours, and, when all options for peaceful surrender had been exhausted, they were met with lethal force.

Like Murphy, Jansen and Lovin had their own flashbulb memories of the incidents, images that they could never shake. For Jansen, it was the viscera that sprayed forth from von George, levitating in the air like smoke, before hitting the ground on its final descent. For Lovin, it was the impact of the bullet as it struck Obergfell dead center in the chest, and then the dying man’s face, his eyes and mouth agog, a rictus of shock. Over 50 years later, Lovin says that he still can’t wipe that face from his memory bank.

The three men spoke about this on a few occasions, but not often. They knew what each was going through, and they all reached the same conclusion: while it was sad that it had to happen, these men had their chances to surrender. They wouldn’t do it.

In life and in death, Sal Naturale was a big unknown. He went by the alias “Donald Masterson.” During the standoff, the press described him as a homosexual, which he denied and wanted corrected. Whereas the whole world knew about Wojtowicz’s dirty laundry, few knew what Naturale looked like, let alone who he was. To those who did know him, he was a “six-time loser” whom “nobody gave a damn about,” according to the New York Times.

The “Sal” the rest of the world came to know was the dimwit played by thirtysomething John Cazale in Dog Day Afternoon—though, in real life, Naturale had been just a lost 19-year-old kid. The movie amped up Naturale’s naïveté to the point of ridicule, which bothered Murphy.

When the film came out in 1975, Murphy took his wife to see it in a packed theater on the Upper East Side. The audience, much like the crowd at the scene of the real standoff, seemed mostly to be on the side of the “bad guys.” When Henriksen, playing Murphy, shoots Cazale, dead center in the forehead, the crowd booed. Murphy wanted to leave before anyone in the audience might recognize him.

“With Murphy’s hand on the back of his neck, Naturale exhaled, flapping his lips, and then stopped breathing.”

Relatives who saw Dog Day Afternoon were indignant, cornering Murphy at family gatherings to ask: “How could you have possibly shot that guy?” They doubted whether he was in the right. “That forced me into a situation of sitting down with my [older] son, who, at the time, was only five, and explaining to him what had happened because I couldn’t allow him to find out from anybody else or to get a distorted view of it,” said Murphy.

But the second-guessing of his actions lasts to this day. Reporter Randy Wicker still thinks that Murphy’s shooting was “cold-blooded murder,” as he did when it happened. “He pushed the boy’s gun to the ceiling and instead of saying ‘freeze,’ he simply shot him in the chest,” said Wicker.

Yet simply to say “freeze” to someone holding a shotgun—with another armed criminal in the car, along with several hostages—could have been a catastrophic misstep, according to Frank Straub, director of the National Policing Institute. In these scenarios, “you’re either going to neutralize the threat or you’re going to be neutralized and, potentially, all the hostages get neutralized,” observed Straub.

Besides, what would have happened had they let the hostages and the robbers board on the getaway plane? No way was the FBI going to let the situation go mobile. And unknown to Wojtowicz, FBI men were waiting for them onboard the plane. If it wasn’t Murphy who stopped Naturale, the job would have fallen to another agent. It’s unfortunate that Naturale was killed. But it happened.

As for Wojtowicz, after serving just five years in prison, he spent the second act of his life parlaying his notoriety in publicity stunts, like signing autographs in front of the same bank he robbed (while wearing an “I robbed the bank” T-shirt). He died of cancer in 2006.

Aron transitioned to Elizabeth Eden, a surgery paid for by the sale of Wojtowicz’s film rights for Dog Day Afternoon. She died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987. Murphy’s son died from cancer in 1992. He was only 12. His death left Murphy in unthinkable pain and in need of a higher calling. At the gentle suggestion of his wife, he pursued the diaconate at his church, becoming ordained in 1999. Being a deacon has brought him the peace and sense of service that he had been seeking. “My son now has what we’re all working toward: salvation. Eternal happiness with the Lord. He’s never going to go through the loss of a child or some of the other heartache that’s around,” said Murphy. “I’m getting up there, so it’s not going to be long before we’re together again.”

Kappstatter interviewed Wojtowicz again in 1979, not long after he left prison. He asked Wojtowicz whether, after the death of a friend, a stint behind bars, the collapse of two marriages, and inspiring a Hollywood movie, he had learned anything.

“Yeah,” said Wojtowicz. “Don’t rob a bank.”

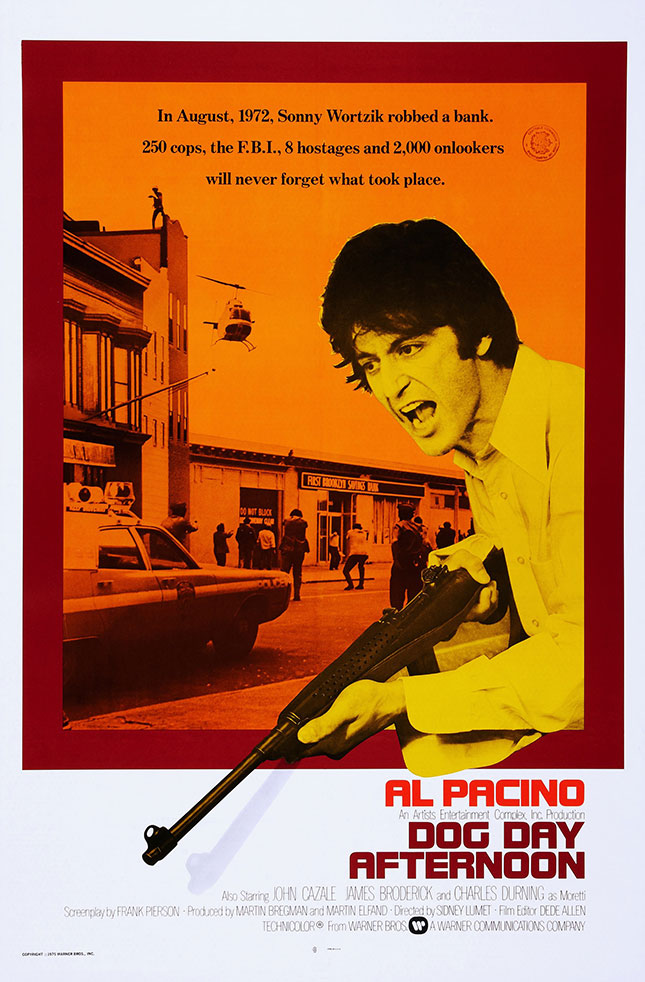

Top Photo: John Wojtowicz gestures outside a Chase Manhattan Bank branch during the infamous robbery and hostage-taking in Brooklyn, August 22, 1972. (LARRY C. MORRIS/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX)