The Covid-19 pandemic provoked well-publicized face-offs around the country between state and local government officials. In western Pennsylvania, four largely rural counties, dominated by Republican representatives, sued Democratic governor Tom Wolf in the spring of 2020 over the constitutionality of his Covid restrictions. A federal judge agreed, invalidating many of Wolf’s limits on everyday activities. Conversely, in Texas, state officials dragged the city of Austin into court in March 2021, after local leaders imposed their own mask mandate in response to Governor Greg Abbott’s lifting of the statewide mask requirement. The suit dragged into the spring, when Austin itself began loosening its mandate as new cases plummeted.

Covid restrictions clearly seem to have exacerbated conflicts between state and municipal officials, particularly in places where one party rules the statehouse and another governs locally. But these clashes have been building for years, and it’s unlikely that the pandemic’s end will quiet them. As municipalities venture into increasingly controversial policy areas once considered the purview of state or federal government, legal battles over policy and legislation seem inevitable.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

One measure of the tensions: the rise of so-called preemption laws, which states use to ban localities from taking certain actions. Over the last five years, states have enacted dozens of these laws restricting local measures or mandates involving labor issues—from higher minimum wages to mandatory paid leave to business-scheduling requirements. Officials in states—which the Constitution empowers to govern as they see fit within their borders, so long as they don’t violate federal law—have argued that preemptions are necessary to prevent a confusing patchwork of legislation that would make it hard for individuals and businesses to conform to the law.

Local officials, by contrast, are demanding greater freedom to fashion policies that respond to their top priorities—which state officials don’t always share. In a statement published in February 2020, before the lockdown clashes, the National League of Cities argued that, with urbanization increasing, America needed a new commitment to “home rule,” giving local governments power over everything from taxation to environmental law to labor policy. As the league’s statement puts it, an imperative exists “for reform grounded in the increasing sense that state oversight is no longer serving the constructive, collaborative role in the state-local legal relationship that it should.”

Unquestionably, the home-rule controversy is partly a function of many American cities coming under the control of far-left politicians seeking to impose radical policies to deal with local problems. That’s caused friction, especially in Republican-governed states, though even Democrat-led statehouses have moved to preempt certain local policies. One of the most common forms of preemption, including by Democratic state legislatures, for instance, are laws banning localities from imposing rent control. With good reason: overwhelming evidence shows that rent control is a counterproductive approach to controlling tenant costs because it cuts the supply of housing that developers produce. Ultimately, state leaders argue, they’re responsible for the consequences of the actions of their local governments, which can be costly. Most states have constitutional limits on how much their municipalities can tax and borrow, for instance, but America’s biggest cities have found ways around those restrictions, resulting in local governments piling up some $333 billion in debt. The 2008 recession brought insolvencies in places like Detroit, Harrisburg, and Hartford—cities that had abused and circumvented fiscal restrictions, demanding expensive state interventions.

The last time America’s cities pushed for greater powers—during the era of home rule in the 1950s—many states acquiesced, and local control expanded. There seems less consensus this time. What’s more likely is intensifying clashes between levels of government, which courts will have to adjudicate.

The United States of America began as a confederation of states, joined together under a common constitution to form a national government granted specific powers. States retained numerous powers for themselves, including, via the Tenth Amendment, the right to organize and regulate their local governments. Across the 50 states, one finds myriad local government systems, with states exercising various degrees of control. During the republic’s early years, when America was mostly rural and many citizens lived in small enclaves presided over by local councils, the limitations that states placed on these local entities generated little controversy. That began to change in the industrializing second half of the nineteenth century, as people migrated to cities, which grew and began to seek greater independence. Many states resisted, bolstered by an 1868 Iowa Supreme Court case in which Justice John Dillon reiterated the principle that municipalities derived their powers from the state. A few state legislatures diverged from this principle by establishing “home rule”—guidelines that allowed municipalities of a certain size to govern themselves more extensively. In 1876, St. Louis became the first city to establish a charter under a new Missouri law giving it home-rule powers.

The next—and most significant—era of home rule began in the 1950s, after the American Municipal Association urged states to grant more freedom of governance to municipalities and drafted a model for how to accomplish that. Many states signed on, with the provision that, though local governments deserved more leeway, states could still preempt their actions through legislation.

That model has more or less endured over nearly seven decades, even as the fortunes of cities have waxed and waned. Social unrest in the 1960s and 1970s reversed the population gains of many cities and shifted some political power to expanding suburbs. Fiscal crises in places like New York and Cleveland, forcing state interventions, and corruption in cities like Detroit and Newark, which many believed fueled riots in those places, undercut the local control ideal. Instead, many city leaders now claimed that they were ill-equipped to deal with the urban problems of the time and needed substantial help from state and federal coffers. This “tin-cup urbanism,” as critics branded it, was far removed from 1950s declarations that cities could be masters of their own destiny.

“Heavily Democratic states like California are among those with the most numerous preemption laws.”

This dynamic started to change only with the urban revival of the last 30 years, as confident leaders argued that the fate of cities was in the hands of those who lived in and governed them. As New York and other cities reestablished social order, economies revved up and budgets stabilized. A new generation of urban migrants—younger and more educated than previous waves—moved to cities, transforming them.

Yet eventually, as cities gentrified, voters began turning to a new type of urban politician, far to the left of his or her predecessors. In New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Seattle, among other cities, progressives have replaced mainstream Democrats, and socialists have built significant power bases. These new urban politicians have proved much less interested in the basics of municipal government, such as picking up garbage and maintaining public order, and more devoted to pursuing grander, vaguer goals involving “social justice”—reducing inequality, ending homelessness, and even using local laws to change habits and consumption practices of residents.

This leftward push has been the source of many recent state–city clashes, though the notion, sometimes expressed in the media, that the confrontations are all about red states versus their blue cities is simplistic. Heavily Democratic states like California are among those with the most numerous preemption laws. And the fight in Pennsylvania between Democratic governor Wolf and the four Republican-leaning counties illustrates how preemption battles can work opposite to the way some media reports describe.

Rent control shows how preemption often evolves. During his 2020 presidential campaign, Senator Bernie Sanders proposed a national law limiting rent hikes. While constitutionally dubious, the Sanders proposal seemed an effort to capitalize on growing calls for rent regulations in progressive jurisdictions. Still, Sanders’s proposal cut very much against the national grain. Thirty-seven states—including not just conservative Florida and Texas but also liberal Connecticut and Washington State—either prohibit or preempt localities from putting controls on rents.

Many of these are among the oldest preemption laws. Connecticut conferred on its municipalities the right to regulate rents in the immediate aftermath of World War II, when prices soared because residential housing construction had slumped during the war, leaving supply short of demand. But as building resumed and prices moderated, Connecticut revoked rent control in 1956, and it has remained banned in the state ever since, through Democratic and Republican administrations. In Massachusetts, meantime, voters in a statewide 1994 ballot initiative nixed rent control, after stories about well-to-do tenants occupying rent-controlled apartments in Cambridge and other locales made headlines. Despite predictions of mass evictions and hardship among fixed-income residents, ending rent control led to few housing disruptions, partly because only a small percentage of those living in controlled apartments were truly needy. Instead, building permits exploded in previously regulated areas, including Cambridge, as new investment in housing took hold.

The impact of rent regulation on housing markets is one of the most extensively studied of urban policies, and its debilitating effects are widely known. “While rent control appears to help current tenants in the short run, in the long run it decreases affordability, fuels gentrification, and creates negative spillovers on the surrounding neighborhood,” wrote Stanford economist Rebecca Diamond in a recent Brookings Institution report. Cities that can regulate rents—among them, New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles—have among the highest rents in the country and, more to the point, produce new housing at some of the slowest rates among cities, relative to population size.

Still, rent control remains a progressive Holy Grail. Covid-19 eviction bans only intensified activist calls to expand rent control, especially in states where cities are becoming politically more progressive. The years ahead will likely witness a resurgence of rent-control conflicts and campaigns to revoke state preemption laws.

Preemption laws revolving around the Second Amendment show how state prohibitions can cut both ways, politically. Only five states lack laws regulating what municipalities can and cannot do when it comes to firearms. In states with such laws, preemptions range from prohibiting municipalities from placing any strictures on firearms (for example, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Kentucky) to giving local governments only limited scope to regulate them (Alaska permits localities to apply zoning restrictions to gun dealers). California has some of the nation’s strictest state gun-control preemptions: “It is the intention of the Legislature to occupy the whole field of regulation of the registration or licensing of commercially manufactured firearms as encompassed by the provisions of the Penal Code,” the law reads.

State laws aren’t permanent, of course. Urbanization has given cities more political clout in state legislatures, often driving changes to preemption laws. Last year, for instance, Virginia’s legislature loosened its municipal firearms preemption, so local governments could enact their own prohibitions against carrying firearms in public places, such as parks and recreation facilities. Several northern Virginia governments, including Alexandria, quickly enacted bans, though most municipalities in the state have not. Oregon legislators are considering similar legislation. Other states have tightened firearms preemptions. Arkansas, Kentucky, and Florida now let state authorities levy fines or misdemeanor charges against local elected officials who violate state preemption laws on firearms.

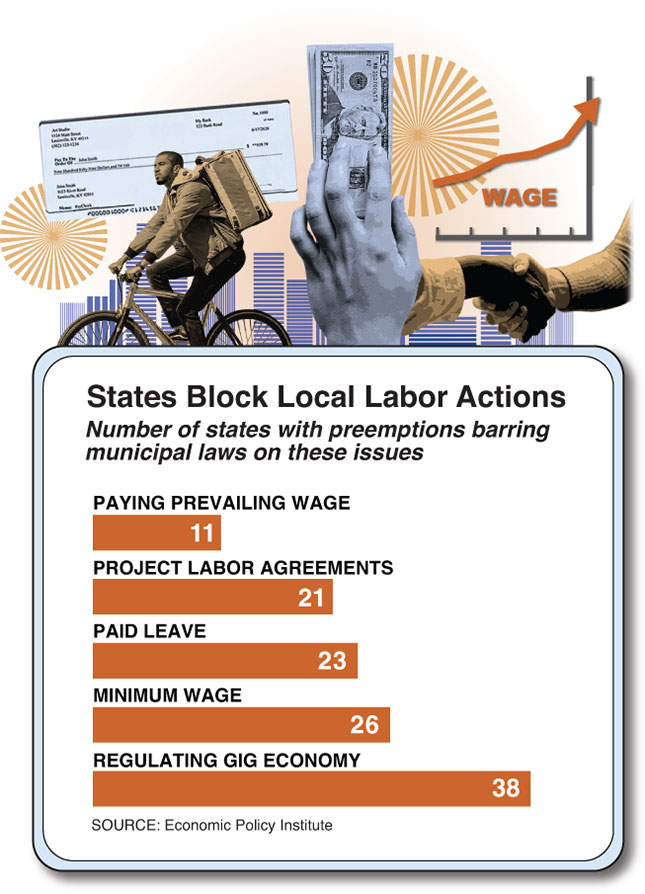

Preemption battles have also been encompassing labor-market issues. While some labor-related preemption laws date from the 1990s, when states like Arizona and Utah banned localities from enacting prevailing-wage ordinances (which require contractors to pay union wages) and requiring project-labor agreements (which can effectively force contractors to use union labor), over the last five years, states have passed 81 labor-law preemptions in response to a changing economy and local government interventions.

A major focus: the gig economy. Thirty-six state governments have reserved the right to dictate laws regulating companies that use independent contractors, with tech-based transportation firms Uber and Lyft being a primary focus. Arkansas, Florida, and Indiana were among the first states to pass laws mandating that drivers for such services—who choose their own work hours and use their own cars but find customers through company apps—be designated as independent contractors, as the companies claim that they are. That ended efforts in municipalities in these states, which often have the right to regulate the local taxi market, to ban or restrict the companies’ activities.

Not all such legislation has favored the companies. In 2019, California passed AB-5, which defined freelance workers in various industries as hired employees—effectively limiting the designation of independent contractors in the state. After a $200 million campaign financed by Uber and Lyft, however, California voters in November 2020 passed Proposition 22, which redefined the firms’ drivers as independent contractors, thereby forestalling local attempts to designate them differently.

The minimum wage is another conflict area. Across the U.S., 45 municipalities have mandated minimum wages higher than their states’ lowest and the federal minimum. More than half these localities are in California, including Los Angeles and Berkeley. But other places have been aggressive, too. Though Washington State’s minimum is nearly double the federal rate of $7.25, Seattle has imposed a lowest rate that scales to $16.69 per hour for employers with more than 500 workers.

Minimum-wage hikes remain controversial because considerable research has found that they destroy jobs—above all, for low-wage workers. Though some recent studies have suggested that wage hikes also reduce poverty, one of the foremost authorities on wage laws, David Neumark, recently wrote, in a coauthored paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, that “there is a clear preponderance of negative” outcomes in wage studies, and this evidence is especially clear for teens, young adults, and the less educated. Of particular concern has been the impact of steep increases like Seattle’s law, sponsored by a socialist member of the city council there, which drew criticism even from Democratic-leaning economists. Following its passage, some Seattle small businesses have shut down, including TanakaSan, one of the eateries of chef Tom Douglas, described as “in many ways responsible for the city’s reputation as a foodie paradise.” Writing in the Wall Street Journal, one of Douglas’s employees, Simone Barron, complained that “being an established chef and a good employer doesn’t save you from the burden of a sharp minimum-wage increase, up 73 percent from $9.47 in 2015.” Out of a job after six years, she sought employment at a restaurant owned by another well-known chef, Ethan Stowell, only to see that restaurant close, too. Describing herself as “proudly progressive” in her politics, she nonetheless observed, “I’ve lived in this city for almost 20 years, supporting my family thanks to the full-service-restaurant industry. Today I’m struggling because of a policy meant to help me.”

Preemption laws in 26 states—ten in the last five years alone—have thwarted comparable wage hikes. When Birmingham raised its minimum in 2016 to $10.10 an hour, the Alabama legislature immediately barred any other municipalities from imposing similar increases. When four Iowa counties tried boosting their minimum wages a few years ago, the Iowa legislature passed a measure prohibiting localities from paying a higher minimum than the state. It’s not just Republican-leaning states like Alabama and Iowa doing this, moreover; Rhode Island’s Democratic legislature passed wage-preemption legislation in 2014, and the state’s Democratic governor signed it into law.

Now cities and some states are pushing new mandates on employers, including requiring firms to give workers paid sick and family leave. Localities including Los Angeles, New York, Montgomery County (Maryland), Chicago, and Philadelphia have all passed paid-leave legislation, typically funded with a tax on employers or employees. In New York, employers now deduct up to 0.511 percent of a worker’s income to fund a mandatory program that gives workers time off to care for sick family members. Since 2004, though, 18 states—among them Florida, North Carolina, and Wisconsin—have banned local paid-leave mandates. Other states have enacted statewide legislation establishing paid leave but preempting cities from requiring more generous terms.

Andrew v. Bill

While many notable preemption battles have broken out between governors and mayors of different parties, the most visible and persistent face-off over the last eight years has involved two Democrats: the mayor of New York City and the governor of New York State. Bill de Blasio and Andrew Cuomo (who resigned in August, facing accusations of sexual harassment) clashed intensely over lockdown policies during the pandemic, sparking debates about where the authority for some of these issues resides in New York. But even before the lockdowns, the two feuded over taxes and control of key institutions in Gotham.

The unique nature of New York City’s government helped foster this tension. Each of the city’s five boroughs is also a distinct state county, but without the power or political shape typical of counties throughout the rest of New York or other states. Instead, city government wields much of the clout. But as the city’s fortunes have risen and fallen over the years, it has at times willingly ceded more to the state. The city owns its subway system, for instance, but it has operated under a state agency, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, since running into financial problems in the late 1960s. The mayor controls New York City’s schools, meantime—but at the behest of state government, which can limit his authority.

Under de Blasio and Cuomo, who have a history of personal clashes, the unusual relationship between city and state government produced one struggle after another. Early in the pandemic, de Blasio debated for three days whether to shut down city schools. As de Blasio faced mounting pressure to act, Cuomo intervened and said that he had the authority to close the education system and was taking it. Soon after, de Blasio decreed that all city residents should “shelter in place.” Cuomo balked, saying that the New York mayor had no power to issue such an order. Three days later, Cuomo decreed that the state would go on a stay-at-home “pause.” Cuomo went out of his way to argue that his decree was dramatically different from what de Blasio had ordered. “Words matter,” he said.

In mid-April 2020, when de Blasio announced that city schools would be closed for the rest of the year, Cuomo bluntly said that the decision would be his, not the mayor’s. He called de Blasio’s order merely “an opinion.” The row sparked some acerbic commentary from other city officials. “Who has legal authority to close down @NYCSchools? That’s a conversation for people with time for largely academic conversations,” tweeted councilman Eric Adams (likely the city’s next mayor).

Such power struggles began even before de Blasio was elected. During his first mayoral campaign, he pledged to raise taxes on city millionaires to fund prekindergarten programs. Cuomo observed that, under state law, de Blasio couldn’t hike income taxes. The two fought during de Blasio’s first year in office, with the mayor trying to persuade Albany legislators to push Cuomo for a new tax. Though Cuomo produced state funding for pre-K, he never approved a city millionaire’s tax. But he did send de Blasio repeated messages about who was in charge.

When, in 2015, a state law enacted seven years earlier giving the mayor direct control over city schools expired, Cuomo renewed it for just a single year, effectively putting de Blasio on a kind of probation. A few years later, Cuomo demanded $400 million more from the city to help finance subways and threatened to garnish Gotham’s property-tax revenues if de Blasio failed to hand it over. He also attached strings to $250 million that the state gave the city to expedite repairs in its public housing agency, requiring that de Blasio appoint an independent monitor to watch over how the city agency spent the money. When Cuomo didn’t have the authority to thwart de Blasio, he had the legislature give it to him via preemption law. After the city enacted 2017 legislation banning stores from using disposable plastic bags, for example, Cuomo signed a law preempting the ban and appointed a commission to study the issue. It wasn’t until three years later, in October 2020, that a subsequent state ban went into effect.

These power struggles—part policy, part personality—have worn thin on New Yorkers. Councilman Adams perhaps best summed up the frustration, when, at one point, he advised both Cuomo and de Blasio: “Cut the crap.”

With Cuomo gone and de Blasio leaving in January, their battles are over. But the governor of New York and Gotham’s mayor have always been the two most visible politicians in the Empire State, and previous governors and mayors have butted heads, too. That’s likely to continue.

The further that municipal officials move away from traditional local policy issues, the more that preemption battles intensify. In recent years, cities and counties have enacted laws banning plastics, regulating and taxing certain foods, and pushing into government-owned or controlled broadband. All have sparked state reactions. Since 2016, ten states have blocked their municipalities from regulating plastic bags or other forms of packaging or taxing these containers, and several others have forced localities to delay their bans until state officials could study the issue; critics argue that the bans don’t reduce pollution and that reusable bags can contaminate food. (See “The Perverse Panic over Plastic,” Winter 2020.) Republican-controlled states like Michigan, Arizona, and Texas have acted in this fashion, but so have Democratic-run states like Minnesota, where the legislature rescinded a Minneapolis plastic-bag ban. Meantime, 14 states have passed laws restricting local actions that target certain foods. Arizona does not allow separate, higher food taxes on products like soda, for example, and California has banned local grocery taxes, including taxes on sugared drinks.

Municipal broadband is the latest battleground, as some cities try to offer residents free network access. Worried that the Internet could wind up solely in the hands of government, 20 states have moved to ban or restrict government broadband—though a few loosened their restrictions temporarily during the pandemic. Most of these preemptions are specific—Pennsylvania and Montana, for instance, allow public networks only in underserved communities. North Carolina doesn’t outright ban the networks, but it establishes conditions, such as prohibiting municipal networks from offering services below cost so that private investment isn’t undercut. States have moved ahead in this area after a federal court denied a 2015 effort by the Federal Communications Commission to preempt state broadband laws. The FCC argued that it had sole purview over broadband, but a federal court ruled that nothing gave the commission the authority to overturn state laws.

In the wake of the riots and protests in June 2020, following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, city officials in some places began pushing to “defund” their police, and some states stepped in with laws to block the practice. After Austin slashed $150 million from its police budget, Texas legislators passed a law enabling the state to reduce funding to cities that cut their commitment to public safety—an area typically considered the purview of local government. The face-off was perhaps best described by the head of Austin’s police union. “The city of Austin’s draconian decisions dealing with the Police Department last year were met with draconian decisions by the state Legislature,” he said.

Expect more of the same.

Top Photo: Former New York governor Andrew Cuomo and New York City mayor Bill de Blasio, both Democrats, battled frequently over everything from Covid lockdowns to education spending. (REUTERS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)