American cities are entering a period of chaos. Protests and riots have dominated headlines, but beneath the surface, activists are launching an unprecedented campaign to overthrow the traditional justice system and replace it with a new model based on a radical conception of social justice.

In Seattle, where this campaign may be most advanced, activists have crafted a narrative about police brutality, mass incarceration, and punitive justice that leads to a natural sequence of solutions: “abolish the police,” “divest from prisons,” and “defund the courts.” Over the past three decades, the city’s radical-progressives have seized control of municipal government—with the notable exception of the criminal-justice system, which they see as the final obstacle to total control. If they can dismantle it, activists believe, they can bring about their transformation of society.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The city’s political establishment has joined the campaign to “deconstruct justice.” Since the outbreak of the George Floyd–related protests starting in late May, elected officials in Seattle and King County have announced their intentions to defund the Seattle Police Department, permanently close the county’s largest jail, and gut the municipal court system. They believe that, when the oppression of the justice system is lifted, a new society can be shaped through criminal diversion, psychotherapy, and harm reduction.

The theoretical underpinnings of this movement can be traced back to the academic currents of “critical race theory,” long pervasive in university humanities departments, which holds that all legal structures—and society generally—can be understood as a function of embedded racism. The law is shot through with white supremacy, critical race theorists believe, which must be rigorously identified and dismantled if true justice is to be achieved. In recent years, critical race theory has expanded beyond the academy and become a force in progressive politics.

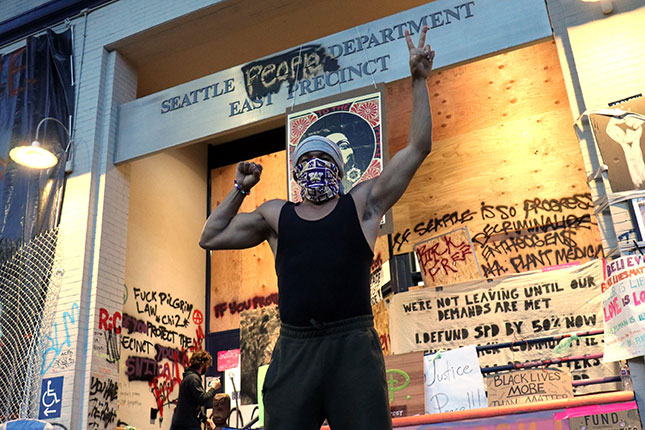

For today’s radical-progressives, the nation’s traditional institutions are little more than vestiges of white supremacy, capitalist exploitation, and colonialist domination. Seen in this light, the recent unrest in America’s progressive cities becomes clear: the chaos is the necessary price—and the accelerant—for the revolution. During the recent occupation of Seattle’s Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, self-described “abolitionist” Nikkita Oliver translated the sentiments of the graduate seminar into the language of the streets, calling for the overthrow of “racialized capitalism” and “patriarchy, white supremacy, and classism.” Motivated by such goals, mobs have seized control of police precincts.

If radicals are successful in moving Seattle toward police abolition, the results will be catastrophic. The city is coming apart. Crime has exploded in the downtown corridor, businesses have barricaded their windows, and citizens fear that the city will collapse into anarchy. Yet the activists and political class are moving forward with their experiment at astonishing speed. Nearly every week, they offer new proposals for transforming the constituent parts of the criminal-justice system. “Burn it down” has evolved from a street slogan into a political platform.

In the progressive narrative, American police forces were established to catch fugitive slaves and have acted as the guardians of white supremacy ever since. As the activist group Decriminalize Seattle argues: “The police have never served as an adequate response to social problems. They are rooted in violence against Black people. In order to protect Black lives, this moment calls for investing and expanding our safety and well-being beyond policing.”

Reform, then, is no answer. The irredeemably racist institution of policing must be excavated root and branch—and then demolished. With this in mind, the Seattle City Council recently released draft legislation that suggests a path for replacing the police with a civilian-led Department of Community Safety & Violence Prevention. The plan is predicated on the idea that “institutional racism” and “underinvestment in communities of color” are the underlying causes of crime. Once the department is abolished and its budget redistributed to minority communities, social workers and nonprofits can keep the peace with a “trauma-informed, gender-affirming, anti-racist praxis”—more activism, in other words. The legislation also calls for race-based redistribution and “the immediate transfer of underutilized public land for BIPOC [black, indigenous, and people of color] community ownership.”

Meantime, to exert maximum pressure from the outside, mobs have been patrolling the streets of residential neighborhoods and paying midnight house calls to wavering public officials. One group, which calls itself Every Day March, has assembled gatherings as large as 300 people and descended on the personal residences of Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan, former police chief Carmen Best, and nearly all city council members. They bang drums, chant slogans, and leave threatening messages on the driveways and doors of their perceived enemies: “Liberate oppressed communities,” “Don’t be racist trash,” “Guillotine Jenny.”

In one incident, the mob marched to the home of Councilman Andrew Lewis after midnight and rousted him out of bed. When Lewis arrived at his building’s entrance, ringleader Tealshawn Turner demanded that he verbally commit to defunding the police. Lewis, standing alone at the gate, was visibly frightened—and he relented, promising to cut the police budget by 50 percent, fire cops with citizen complaints against them, and redirect millions to “communities of color.” Having extracted her demand, Turner left with another threat: “If you don’t keep your promise, we’re for sure coming back.”

Even as chaos engulfed Seattle, the city council passed a measure depriving police of essential crowd-control tools, including pepper spray, tear gas, blast balls, and stun grenades. In a desperate letter to business owners and residents, Chief Best warned that officers had “no ability to safely intercede to preserve property in the midst of a large, violent crowd.” In essence, she was announcing the end of law and order within the city.

“Policymakers have laid out a rationale to close the region’s largest jail and end youth incarceration.”

Though the crowd-control munitions ordinance was blocked by a judge hours before taking effect, one veteran cop told me that the activists have settled on a bare-knuckled strategy: reduce police power enough to achieve “mob rule” in the streets. If the activists can defund the police and disarm officers, they can break the state’s monopoly on violence. Whenever it can mobilize a crowd of 250 people or more, the mob will dominate the physical environment.

Yet despite rising street disorder and intimidation of public officials, 53 percent of Seattle voters in a recent telephone poll supported the plan that would “permanently cut the Seattle Police Department’s budget by [half] and shift that money to social services and community-based programs.” According to police officials, officers are in “disbelief.” They find themselves besieged both on the streets and in city hall.

For now, the chaos-to-revolution strategy has the momentum. As black-clad mobs smash the windows of banks and storefronts, the city council has voted for budget cuts that set the stage for police “abolition,” and activists have pushed out Chief Best through a campaign of legislative humiliation and political intimidation. “Our leadership is in chaos,” says one frontline cop. “The mayor has made a decision to let a mob of 1,000 people dictate public safety policy for a city of 750,000.”

Prison abolition has long been a goal of radical movements, from the storming of the Bastille during the French Revolution to the jailbreak of Kresty Prison during the Russian Revolution. In modern-day Seattle, though, the revolution is developing from within. According to a set of leaked documents that I obtained from inside the King County Executive’s Office, policymakers have laid out the rationale for permanently closing the region’s largest jail and ending all youth incarceration—including for minors charged with serious crimes such as rape and murder.

The documents cast the prison system as an institution of “oppression based on race and built to maintain white supremacy.” In a pyramid-shaped graphic, policymakers claim that crime and incarceration are merely the “tip of the iceberg.” On a deeper level, the justice system is rooted in “white supremacist culture,” “inequitable wealth distribution,” “power hoarding,” and the belief that “people of color are dangerous or to be feared.” Once these premises are established, the conclusion is foregone—white supremacy must be eradicated. To this end, days after I released the internal documents, King County Executive Dow Constantine announced a plan for terminating youth detention and closing the downtown Seattle jail, which represents approximately two-thirds of the county’s jail capacity. More than half of all inmates are incarcerated for violent crimes; the plan will release such violent criminals onto the streets.

County corrections officers, who were not consulted on the executive’s surprise announcement, were horrified. One senior manager told me that “activists [are] seeking to rewrite the narrative of society,” and, if the shutdowns come to pass, “the ones who will suffer in the end are [people of color], as crime skyrockets and lawlessness becomes the norm.” Frontline correctional officers and medical staff within the jails are in a state of “chaos” and bracing for “mass layoffs,” the manager told me. According to the internal documents, the county executive warned his team to expect “stress, confusion, and a sense of overwhelm” within the department, but reassured them that this should not impede their work to create a “shift in power structure” that would let “internal discrimination and racism come to the surface.”

What will replace jails? According to Budget for Justice, the leading coalition of the progressive-justice movement, the government should “transfer resources from formal justice systems to community-based care” programs “rooted in restorative justice practices that are trauma-informed, human rights-, and equity-based.” Specifically, the activists highlight three nonprofit programs as models for the new justice system—Community Passageways, Creative Justice, and Community Justice Project—which will offer programs such as “healing circles,” “narrative storytelling,” art-based therapy, and community organizing. The three providers share a philosophical foundation predicated on the assumption that poverty, racism, and oppression force the dispossessed into crime and violence. The programs are designed to reveal how “systems of power create conditions that perpetuate violence in our homes and daily lives” and help offenders “reimagine a society in which their liberation is not only possible, but sustainable by the community itself.”

Though these programs are ideologically aligned with revolutionary goals, they have failed to serve as practical replacements for the “formal justice system.” In one high-profile case, prosecutors diverted a youth offender named Diego Carballo-Oliveros into a “peace circle” program, in which nonprofit leaders burned sage, passed around a talking feather, and led Carballo-Oliveros through “months of self-reflection.” According to one corrections official, prosecutors and activists paraded Carballo-Oliveros around the city as the “shining example” of their approach. However, two weeks after completing the peace circle program, Carballo-Oliveros and two accomplices lured a 15-year-old boy into the woods, robbed him, and slashed open his abdomen, chest, and head with a retractable knife. The victim placed a desperate phone call to his sister and a passerby called an ambulance, but the youth later died at the hospital.

Despite public setbacks and no tangible record of successful alternatives, County Executive Constantine is moving forward with his plan to close the downtown jail and end all youth incarceration. For activists, however, the revolution is not happening fast enough. To increase the pressure, they dispatched a mob to Constantine’s home one night to demand that he speed things up. They shouted him down and shook cans of spray paint, calling on Constantine to release all youth prisoners, including minors charged with murder, because “the police are murderers all the time.” Constantine, standing under a streetlamp with his arms crossed, tried to placate them.

Seattle’s activists have long sought to limit the scope and authority of the municipal courts. For years, influential organizations such as Budget for Justice and the Public Defender Association have advocated for eliminating cash bail, ending probation, reducing the number of municipal judges, and easing sex-offender registration requirements—all under the rubric of “dismantling systems of racism, oppression, and poverty.” Now, with momentum from Black Lives Matter, the activist coalition is mobilizing behind a much more ambitious agenda: abolishing the municipal court altogether and transferring authority to a “shadow court system,” administered by ideologically aligned nonprofit organizations such as Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), which provides “crisis response, immediate psychosocial assessment, and wrap-around services including substance-abuse disorder treatment and housing”—that is, replacing the punitive state with a therapeutic one.

The reforms put into place so far are already spiraling into anarchy. In recent years, Seattle has become a haven for tent encampments, public drug use, and street disorder, and the city now has one of the nation’s highest property-crime rates. LEAD, which receives $6 million in annual city funding, has repeatedly failed to produce results. In its original “scientific study,” when controlling for old warrants, LEAD had no statistical effect on new arrests—in other words, participation in LEAD was as effective as doing nothing. Despite mounting skepticism from the public and even Mayor Durkan, LEAD executives have refused to release detailed recidivism data since 2015, even hiding critical participant information from municipal court judges.

Finally, last year, following a series of high-profile “repeat offender” cases, Seattle Municipal Court Judge Ed McKenna tried to raise the alarm about the city’s failure to prosecute career criminals like Francisco Calderon, a homeless man who had garnered more than 70 criminal convictions but continued to secure jail-free plea deals from the prosecutor and public defender’s offices. The Calderon trial was widely covered in the media and dovetailed with an explosive report about the city’s “prolific offenders” who had been terrorizing residents and businesses. But McKenna’s call to restore public order provoked a powerful backlash. Almost immediately, progressive leaders—City Attorney Pete Holmes, Public Defense Director Anita Khandelwal, and LEAD cofounder Lisa Daugaard—waged a public-relations war against the judge and pressured him to retire two years before the end of his term.

Judge McKenna warns that the progressive-justice coalition is perilously close to establishing a shadow court system. He argues that Holmes, Khandelwal, and Daugaard are becoming “modern-day lords and landowners,” with the power to dispense justice outside the constitutional framework. McKenna believes that nonprofit diversion programs, which exist beyond the confines of the state and are not subject to meaningful public oversight, are potentially violating the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees the right to a public trial before a jury of one’s peers. “In [pretrial diversion schemes], potential defendants are contacted by prosecutors and told that if they ‘voluntarily’ participate in specific programs, criminal charges will not be filed against them,” McKenna says. “The ethical concern, however, is whether accused persons are waiving their rights ‘knowingly and voluntarily’ or whether accused persons feel compelled to waive those rights under threat of prosecution and jail.”

Despite such concerns, the campaign to replace traditional justice with activism continues. After the George Floyd–related unrest, dozens of King County prosecutors, organized as the Equity & Justice Workgroup, issued a letter encouraging their own office to stop filing charges for assault, theft, drug dealing, burglary, escape, fare evasion, and auto theft. In effect, they want to move all but the most serious crimes into the nonprofit-diversion process. Meantime, LEAD, seeing a chance to extend its power, severed ties with the Seattle Police Department and declared its intent to move “beyond policing” and serve as the centerpiece of the new progressive-justice complex. According to several sources with whom I’ve spoken, a sense of foreboding is pervasive within the municipal court. Its officers believe that their entire branch of government, designed to provide an open forum for justice and a bulwark against tyranny, could be obliterated.

“The system does not wish to be remade and it resists remaking,” Daugaard told reporters. “And there’s no doubt that we would not be having anything like the scale of a redesigned conversation that is occurring if not for the top-line demands of people in the street.”

In Seattle, the movement to “abolish the police, prisons, and courts” is not simply the dream of marginalized radicals; it has also been adopted at the highest levels of municipal government. Activists have demanded that the public imagine a world beyond justice, and the political class is trying its best to imagine it, too.

These modern remakers of society are not hoping to achieve new policies within the given social order. Rather, they are looking to overturn that social order completely. “We are preparing the ground for a different kind of society,” declared socialist city council member Kshama Sawant in a recent committee hearing. “We are coming to dismantle this deeply oppressive, racist, sexist, violent, utterly bankrupt system of capitalism—this police state. We cannot and will not stop until we overthrow it and replace it with a world based instead on solidarity, genuine democracy, and equality—a socialist world.”

Though the new revolution is couched in the language of science—its programs are “data-driven” and “evidence-based”—the real objective is a revolution in values. The activists seek to establish what might be called a “reverse hierarchy of oppression,” destroying the final remnants of tradition, law, and order, and establishing the dominance of the outcast, the minority, and the oppressed. In the leaked documents from the county executive’s office, policymakers suggest that prisoners should be seen as society’s legitimate “rights holders” and that the “government is responsible for the problem [of crime]”—society is the criminal, on this view, and the criminal is the ideal citizen. It’s a disorienting inversion of values.

In reality, the progressive revolutionaries are replacing traditional justice with street justice; they are supplanting the rule of law with the rule of the mob. The early results of this experiment are sobering: armed gangs roam downtown, while fatal shootings are up nearly 50 percent from last year. For the first time in living memory, the police department is losing its position as hegemon of the streets. The rioters of the Every Day March have begun to descend on residential neighborhoods, demanding that white homeowners “open [their] wallets” and “give black people back their homes.” As they move down the street, they chant in a call and response: “Who do we protect? Black criminals!”

One veteran Seattle police officer told me that he thinks that the recent disorder is merely the prelude to a long and dark era for the city. “Derek Chauvin is the Gavrilo Princip of our time,” the officer said, comparing the Minneapolis police officer charged with murdering George Floyd to the Serbian assassin who sparked World War I. “The tide of public opinion is on the side of the activists, and they’re pushing the envelope as far as they can. It’s not hyperbolic to say that the endgame is anarchy.” But anarchy, too, is a feature of the revolution. The activists leave no room for grace, humility, or continuity. Like their historical predecessors, they will burn down entire cities in a fevered search for utopia.

Top Photo: Police clash with protesters in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle in July. (GRANT HINDSLEY/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX)