At 9:45 AM on May 18, 1927, explosions ripped through the Bath Consolidated School outside Lansing, Michigan. At first, witnesses and survivors didn’t know the cause. But within half an hour, as rescuers worked within the school, a man drove to the scene in a truck loaded with dynamite and detonated it, killing himself and four bystanders. In total, the dynamiter, Andrew Kehoe, killed 44 people with the two explosions, most of them children.

Even in an age like ours, well acquainted with school violence, the Bath School massacre can be shocking to learn about. Perhaps the most surprising part of the event, however, is the motive. Kehoe was a trustee and treasurer of the Bath School District, but he had recently lost his house in a foreclosure. Afterward, the local sheriff heard Kehoe mutter, “If it hadn’t been for that $300 school tax, I might have paid off this mortgage.” Kehoe had clearly gone mad, but the focus of his rage, against the world and the school, was centered on high property taxes.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Americans became obsessed with property taxes. Like their better-known descendants in the 1970s, these Americans spawned a tax revolt that moved a seemingly mundane issue to the forefront of national consciousness. Though occasionally destructive, the revolt found broad support among all segments of the population and eventually led to the reform of the tax system.

Today, the property tax rarely makes headlines, but it is essential to American life. About 3 percent of Americans’ income goes to property taxes. The levy is the foundation of local governments, accounting for nearly three-quarters of their taxes and underpinning their school systems. Without the property tax, independent local governments could not exist.

Economists generally argue that the property tax is a good tax, since much of it falls on immovable land that can’t be hidden, created, or destroyed and since the revenue it generates is tied to the services that local governments provide. The stable nature of the tax during the recent pandemic showed some of these virtues.

Yet the public seems to disagree. Surveys show that Americans hate the property tax more than any other local, state, or federal levy—and by wide margins. New York governor Andrew Cuomo, no tax cutter, convinced the state legislature in 2011 to cap property taxes and in 2019 to make the cap permanent.

Maybe calling the property tax a “good tax” is a stretch—but when properly administered, it is the least bad tax. The problem: state and local laws have attenuated the tax’s connection to local benefits, made it a tool of redistribution, degraded the transparency of its administration, and expanded the shadowy districts that receive its revenues.

Earlier generations showed how to turn a bad property-tax system into a good one. If we heed their lessons, we can fix the system again. In the process, we can bolster the one part of our political system that most Americans remain happy with: local government.

The most important benefit of property taxes, which economists have touted for decades, is that Americans cannot maintain truly local government without them. Governments in small areas need to levy taxes that won’t cause people to run next door. Income taxes are more likely to make people flee, and only a few cities in the country, mostly in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York, impose them. Outside New York City, local income taxes are usually about 1 percent. Likewise, since a high sales tax in one location will cause shoppers to go elsewhere, states usually impose uniform sales taxes, either giving some of this revenue back to local governments or letting the local governments add 1 or 2 percentage points extra.

By contrast, property taxes give local governments some leeway to set their own rates and therefore derive their own source of revenue. It’s a tax not on people but on things, such as land and buildings, which can’t move. The tax can also be tied to explicitly local benefits, such as schools, parks, and police and fire protection. Appropriately managed, a property tax is a “benefit tax,” meaning that it is more like a fee that one pays for specific services.

Property taxes also encourage localities to govern well. When governments offer good services at low cost, the added value gets “capitalized” in the value of land and homes. People pay more to live in towns with good schools, clean streets, and low taxes. These “homevoters,” as economist William Fischel calls them, have a financial incentive to keep the government running well: namely, to improve the value of their homes. They act like interested shareholders and get more involved in their communities.

Political scientists and economists have long argued that small and competing governments tend to be more efficient than large regional governments or state governments. Stanford professor Caroline Hoxby has shown that areas with competing school districts, for example, have better and cheaper schools than those with large, centralized districts. Vying with one another, local governments tend to be more responsive than distant ones to voters. Decades of studies have shown that when property values, and therefore tax revenues, suddenly increase in small towns and suburbs, these places tend to return those funds to the taxpayers. But state and federal governments rarely do the same with sudden windfalls. The reason is simple: the local governments already provided the “right” level of services and benefits to their voters. The extra tax money was a boon that they returned. Thus, local governments that subsist on property taxes often provide good services at low cost.

Why, then, did the property tax become so despised, starting a century ago? To private citizens back then, it was the “most hated tax.” To experts such as Edwin R. A. Seligman of Columbia University, then the nation’s foremost tax scholar, it was the “worst tax.”

In the early twentieth century, the property tax had indeed become outmoded and outdated. Despite claims that the tax supported local benefits, states captured much of the tax revenue and kept up to 50 percent of the total for themselves, according to economist John Joseph Wallis’s “History of the Property Tax in America.” This meant that local assessors (who valued the property to be taxed) and local voters (who elected the assessors) had reason to keep taxes down, since much of the increased value got siphoned away.

“Maybe calling the property tax a “good tax” is a stretch—but when properly administered, it is the least bad tax.”

Many states also had “uniform” and “universal” clauses in their constitutions, which stipulated that all property, not just real estate, should be taxed at the same rate. This meant that every piece of furniture, every tool, and every stock certificate had to be announced to the local assessor. While the ability of the wealthy to stuff bonds and expensive pieces of art in the walls became legendary, farmers, with their large plots of unconcealable land, bore the brunt of the tax. And the powerful and the connected had other ways to exempt themselves: assessors were often tied to political machines and exhibited favoritism.

Most concerning for taxpayers was that property taxes kept going up. They consumed 3 percent of national income in the early twentieth century, rising to 5.4 percent in 1929, and then, in a collapsing economy, soaring to 11.7 percent by 1932—a proportion never matched before or since. At the height of the Great Depression, writes David T. Beito in Taxpayers in Revolt, about one in every four households had stopped paying property taxes. When numerous groups declared “tax strikes,” they were acknowledging the inevitable. People didn’t have the money; they couldn’t pay.

High property taxes were not a partisan issue. As governor of New York, Franklin Roosevelt worked to lower local property taxes, and he made reducing the property-tax burden part of his presidential campaign in 1932. Roosevelt’s presidential predecessor, Herbert Hoover, also railed against high property taxes in his campaign, though he knew that the federal government had almost no power over the situation.

The 1930s did bring reform. During 1932–33, 16 states set maximum tax limits, allowing local governments to take no more than a set amount, often 1 percent or 2 percent, of property values. Almost every state relinquished its claim to the property levy—often substituting sales and income taxes in their place—and let local governments keep all the revenue. States ended their universal and uniformity clauses and lifted taxes on personal property and financial assets. They professionalized and de-politicized assessors, even as they gave local governments more leeway to determine what types of property got taxed. Governments at all levels soon enacted homestead exemptions, letting everyone deduct a certain proportion of his home value from the tax bill and freeing the poorest from property taxes entirely.

States also gave more authority to local governments, especially in the suburbs, to incorporate and administer themselves—and to keep their tax dollars out of the hands of urban political machines. Instead of having one dominant metropolitan government that could tax its residents at will, center cities now had to contend with suburbs on both services and taxes. Despite claims that such suburbs “bled” the cities of tax money, these competing governments kept all elected leaders responsive to their constituents.

For the next 30 years, property taxes worked like the new crop of economic and public-finance experts said that they should. The reliance on property taxes turned suburban governments into growth machines that demanded new development. Many suburbs used their new autonomy to overvalue and thus overtax new developments relative to old property, which became known drily as the “welcome stranger” policy. Yet the extra property-tax benefits of such new projects made them even more enticing to local voters. As one San Francisco Bay Area newspaper said, in supporting new development on nearby pastureland, “Cows don’t pay taxes!” Locals tailored the property taxes to meet their needs, and it seemed to work. Cities and new suburbs grew and expanded, taxes were reasonable, and local schools and amenities found broad support.

But a host of changes—first scandals, and then overreactions—upset the cheery age of the property tax yet again. In the 1960s and 1970s, a series of investigations of assessors in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Chicago found political skullduggery and haphazard assessments that rivaled the worst of the old days. New laws aimed to standardize and “modernize” assessments on property and make them uniform, so that all property, at least in real estate, would pay the same rate. Some state supreme courts—for example, in Massachusetts and New York—mandated uniform assessments. Reformers and jurists argued that downtown skyscraper and industrial owners had gotten tax breaks for too long and that homeowners were getting shortchanged.

The reformers were wrong. Whenever a “modernization” occurred, it became clear that commercial and industrial property had been overtaxed, and homeowners undertaxed, relative to a uniform standard. This made sense because homevoters, not businesses, elected the local governments; but to many, it came as a rude surprise. Modernization led to a surge in charges for homeowners—and to understandable outrage. In California, all property taxes rose after modernization in 1966, but the proportion paid by homeowners jumped by one-third.

“Studies have shown that equalization hurt school quality and tended to lower test scores in states that implemented it.”

Standardization had some virtues, but the rigid rules generally prevented local governments from tailoring taxes to their needs and burdened many poor and elderly homeowners with explosive charges. Such surprising bedfellows as the National Welfare Rights Organization, radical organizer Saul Alinsky, and Republican taxpayer groups worked together to limit increases. As Isaac Martin points out in The Permanent Tax Revolt, almost every state “modernization” push was followed by a property-tax revolt.

But the most important and damaging change to property taxes came from another sort of standardization, this one on the spending side: namely, where the tax revenue went to. Previously, school finance was the principal use of local property taxes; besides a few grants from the state, locals paid for and ran their own schools. Even today, half of all property taxes go to schools. Yet advocates have long argued that the connection between property taxes and schools was unfair, as it led to racial and economic inequities. At least since Arthur Wise’s 1968 book Rich Schools, Poor Schools, advocates have called property-tax-funded schools inequitable and unconstitutional. In the famous 1976 case Serrano v. Priest, the California supreme court agreed, declaring that every school district had to spend the same amount on every child. Similar “equalization” court rulings in other states reached their peak in the 1990s and changed the shape of local governments.

After equalization rulings, states began to centralize financing again. When a Kansas court struck down the state’s school-finance system, the legislature had to reimpose the old state property tax in 1992 and redistribute the funds to any district that was “underspending.” After the Texas supreme court made a similar ruling, the state legislature created a “Robin Hood” tax in 1993, which collected “excess” property-tax money from well-off local school districts and distributed it to others. In other states, elected officials responded to threats of litigation and centralized financing themselves.

The problem with these rulings, then and now, lies in confusing poor school districts with poor people. Research from the 1970s to today shows that minorities and poor people were actually more likely to live in the richest districts. These groups often lived in center cities that had loads of commercial property to tax. Ironically, this led to school districts in cities with many impoverished students, such as San Francisco and Austin, Texas, sending money to middle-class suburbs with lots of homeowners but few commercial properties.

The negative ramifications of equalization laws affected all aspects of local government. School-finance reform severed the link between good school districts and the value of local homes. Consequently, homeowners took less interest in their local districts. Studies have shown that equalization hurt school quality and tended to lower test scores in states that implemented it. It also led to cuts in school spending. After the Serrano case in California, voters passed Proposition 13 by a nearly two-to-one margin, rolling back assessments and limiting property-tax increases to 2 percent yearly. A similar proposition before Serrano went down by two to one. The difference was that, after “equalization,” voters decided that if their property-tax payments were just going to be stolen, they might as well not pay them. California went from leading the nation in both the quality and funding of its schools to becoming a perpetual laggard.

States also changed what types of governments get the property tax. Some made it harder to create new suburban municipalities; others tried to organize regional governments or force county-city consolidations. With less competition, urban areas imposed higher, even confiscatory, property taxes. Many studies show that small, competitive local governments tend to return any extra tax revenue to taxpayers; those same studies show that when large urban centers get increased assessments and taxes, they use them to boost their budgets. The same goes for state and federal grants to these big cities or regional governments. Larger cities manifest more of what economists call the “flypaper effect”: new money sticks wherever it hits, no matter what voters want.

Large urban centers turned the property tax into just one of many local levies, damaging their own cities as a result. While most of the U.S. imposes property taxes of about 1 percent of the value of property, rates in such cities as Detroit and Camden, New Jersey, run to 3.5 percent—and residents receive atrocious services in return for these punitive levies.

While states have made new municipalities harder to form, they’ve made it easy to create “special districts.” Most Americans are at least familiar with their city government and their school district, but they are likely oblivious to the array of special districts that may overlap their home, administering everything from water and sewer services to fire departments, hospitals, and mosquito-prevention programs. These districts can impose property taxes and issue bonds with little voter input. Since the 1980s, states have created more than 8,000 local governments, 96 percent of them special districts. According to the U.S. Census, more than 51,000 of these districts exist today across the country. Most Americans couldn’t name one of them.

Competing local governments are a good thing, but overlapping local governments prevent accountability and drive up taxes. Studies show that areas with more overlapping districts, with California and Illinois being the two champions in this regard, tend to have higher taxes and less responsive services.

Perhaps the most pervasive, and least justifiable, of these are Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts. These districts claim to rejuvenate “blighted” urban property by issuing bonds and giving subsidies to local developers. In return, the districts get to keep all the increases in property taxes after they were formed, on the assumption that the TIF district improved the land value and thus earned the extra increment. Yet, on average, the land inside TIF districts gains no more value than the land outside them. And a study of Wisconsin TIF districts showed that almost half were on greenfield land, not deteriorated inner-city districts. In some cities, TIF districts become a burden for the other taxpayers, who have to pick up the fiscal slack. In Chicago, $1 billion sits in TIF funds, spread over more than 100 TIF districts. The total city budget is about $6 billion.

In some states, these districts have become notorious “redevelopment authorities,” issuing bonds based on property-tax increases, using the money to buy up local property through eminent domain, and giving the property to eager developers. In California, the redevelopment authorities spread rapidly because they circumvented school-equalization rulings. Whatever money went to redevelopment authorities didn’t go to local school districts, which themselves just redistributed money to the state. Governor Jerry Brown ended such redevelopment districts in California in 2011 precisely because doing so meant that the state had to spend less money “equalizing” school districts. (See “California’s Secret Government,” Spring 2011.)

States have also become ever more generous in encouraging the rise of nonprofit economic empires—especially hospitals and schools. In many cities, up to one-third of all property is exempt from taxation. In Boston, about half of all real property is exempt from property taxes, putting the onus on the city’s shrinking for-profit sector. These rules leave homeowners, rental-property owners, and private companies bearing the burden—and wondering who the real beneficiaries of the property tax are.

Finally, the ongoing proliferation of special districts, TIF districts, and exemptions has made it harder for local voters to see the financial benefits of new development. Thus, they tend to be less welcoming of new housing. The more that property-tax dollars get siphoned away, the less that local voters see growth as a benefit.

“Voters don’t want to get rid of property taxes entirely. They want local control and some basic state guardrails.”

But the property tax can be fixed again. Despite voters’ supposed hatred of it, they loathe turning funding and control over to the state even more. Before judges intervened, five states, including California, held referenda in the 1970s on reducing local property taxes and funding their schools at the state level. The voters rejected them all by wide margins. Similarly, a North Dakota initiative to centralize school financing in 2012 went down to an overwhelming loss.

Voters may not like high property taxes, but they don’t want to get rid of property taxes entirely. They want local control, local input, and some basic state guardrails. Returning power and funds to local governments will once again make them responsive to voters.

First on the list of reforms should be the assessment system. Since the standardization debacles of the 1960s and 1970s, states have created more breaks from uniform taxation levels, some for the better and some for the worse. Breaks for agriculture and the elderly should remain. Though some rail at the inequity of these exceptions, cities understand that farmers and the elderly use less of the social services, especially schools, that represent the main benefit of local governments. Yet states have gone far beyond such exemptions, turning the property-tax code into just another way to dole out favors. Tax exemptions now exist for veterans, the disabled, historic properties, affordable housing, blighted property, pollution-control equipment, solar panels, wind energy, geothermal heating, and so on. Minnesota now has 55 classifications, each with its own rate. The many classifications should be standardized into a few basic categories. States should also stop assessing the personal property and equipment of businesses; personal-property taxes currently discourage manufacturing and industry. (See “Can American Cities Manufacture Again?,” Winter 2020.)

States should also rein in the proliferation of special districts, TIFs, and redevelopment authorities. All extract revenue from taxpayers while operating in the shadows. Many should be brought under the auspices of local municipalities.

Some basic transparency rules for local governments will also help. Utah’s 1985 “truth in taxation” law and its many progenitors require governments to notify citizens and hold public hearings when tax revenues exceed expectations and the governments don’t return them to taxpayers. Sudden increases in assessments shouldn’t cause spikes in spending, and such laws prevent the flypaper effect from happening automatically and give voters a say in any new spending.

A major virtue of the property tax in its mid-twentieth-century golden era was its transparency. Only local governments collected property taxes, and most voters knew where the money went. Now, multiple impenetrable governments and countless state tax and redistribution schemes make it impossible to know what the tax is really funding. In California, to take a representative example, local governments still collect property taxes—but the amount collected has nothing to do with the amount spent, so taxpayers don’t know whom to get mad at. Restoring transparency is imperative.

Most important, states should push back against equalization and return more funds to the school districts and localities that collect them. Right now, property taxes are themselves effectively taxed by state governments and given away to other governments. This helps neither students nor homeowners. Control and funding of school districts should be returned to local parents and taxpayers, even as more charter school and private school competition in the largest districts is permitted. The state should support needy students without assuming, falsely, that they live only in “poor districts.”

As in so many things, America’s dependence on local property taxes is exceptional. U.S. property taxes, as a percentage of income, are 50 percent above those of other developed countries. Even in countries that do impose property taxes, it is just one national levy among many. In the U.K., local governments are generally powerless conduits passing down cash from on high. People who vote in local elections around the world generally don’t get to determine how much government they want, or what they want it to spend money on.

But Americans rely on local government. Despite recent centralization, 15 percent of all U.S. tax revenue, mainly from property levies, still comes from local governments. In the U.K. and Belgium, that figure is only about 5 percent. Americans have real discretion in these localities to express their views on education, urban noise, parks, and public works. Without our local property-tax funding, we would lose our ability to accommodate the diversity in American lifestyles and preferences—and to elect local officials who will respond to their constituents.

To believe in one’s local government is to believe in the property tax—but if we are to believe in the property tax, we need to fix it. It must be made more like a fee for good local service and less like a general revenue-raising tool. With some tinkering, the tax can become a benefit once again.

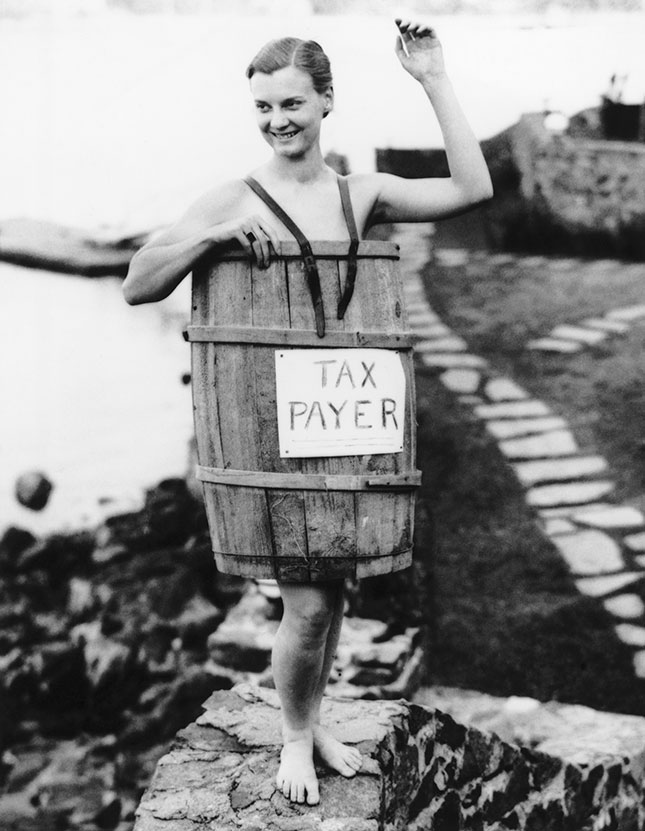

Top Photo: California’s Proposition 13, limiting property-tax increases to 2 percent yearly, passed by a nearly two-to-one margin in 1978. (TONY KORODY/SYGMA/GETTY IMAGES)