In August 1844, a ne’er-do-well 25-year-old named Herman Melville disembarked from the USS United States in Boston harbor. The second son of a once-respectable New York City family—broke and mad, his businessman father had died 12 years earlier—he had neither measured up to his pious mother’s expectations nor found steady employment. He’d made his first getaway in 1839, signing on as cabin boy on a merchant ship sailing between New York and Liverpool. The next year, after a brief stab at teaching, Melville was on the road again—west on the Erie Canal, then over the Great Lakes to Chicago, downriver to southern Illinois, and then back east on the Ohio River—all in a failed quest to find gainful work as a surveyor. After another short stay in New York, he went up to New Bedford, talking his way into a job on the whaling ship Acushnet. His brother said that he’d “never seen him so completely happy” as on the day the ship sailed.

Reality quickly set in. Captains of whaling ships ruled their polyglot crews with a severity intolerable to a young man who admired his fellow Americans for their “genuine republican swagger.” The captains brooked no such swagger in their crews, upholding the doctrine that all men are created equal—equally subordinate to their captain. For nearly four years, Melville experienced the democratic despotism of life at sea under captains on three whaling ships, jumping the first one in the Marquesan Islands, where the local tribe treated him to four weeks of plentiful food and playful girls, perhaps intending to fatten him up for their own cannibalistic feast. Escaping to an Australian ship, he participated in a mutiny, and got on another whaler, which brought him to Honolulu, where he submitted to the slightly more benevolent despotism of the U.S. Navy on the vessel that would carry him back to America.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The nation he returned to in 1844 was about to elect James K. Polk to the presidency. Along with Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois and former president Franklin Pierce, Polk was part of a new intellectual and political movement that marked a generational shift in the American conception of the right basis for law and policy. Taking up where the Jacksonians had left off, the “Young America” movement found its galvanizing slogan in the writer John L. O’Sullivan’s call for achieving our “Manifest Destiny” to rule the remainder of the North American continent. While staying within the dominant Democratic Party, Young America combined the long-standing Democratic policy of free trade and low tariffs with the Whig Party policy of internal improvements—infrastructure designed to hasten the advance of Americans to the Pacific Coast.

The Young Americans tried to settle the slavery controversy that threatened the Union by valorizing popular sovereignty in a way that the American Founders hadn’t done. The Founders located sovereignty in the people, but the people had to be ruled by the greater sovereignty of the laws of Nature and Nature’s God. Consistent with these principles, Congress had banned slavery in the territories that the Northwest Ordinance governed. By proposing that newly acquired territories west of the Mississippi be authorized to vote slavery up or down, and then be admitted as new states of the Union based on those majority decisions, Senator Douglas and Young America generally were “blowing out the moral lights around us,” as Abraham Lincoln put it in his debates with the senator, a decade later. Young America was arguing that majority rule—a form of might, not moral law—made right. Melville’s experience—and his greatest work—cast light on the potential costs of such a conception.

Melville had just voyaged on the boundless sea, where might is indeed taken to make right, whether in the form of a captain on a ship or of a monstrous Leviathan beneath that ship. He initially supported Young America, publishing in several of its literary journals. His sympathies were engaged by the movement’s intellectual wing, centered in New York, which set itself against the genteel literary traditions of Boston and proudly insisted, as Melville would do in one essay, that America would one day surpass England in literary productions—that the Ohio Valley would raise up rivals to Shakespeare.

Young America’s political aspirations he viewed more skeptically. Writing to his brother in June 1846, Melville reported that “people here”—he was visiting his family in upstate New York—“are all in a state of delirium about the Mexican War.” Though the main political issue that the war raised concerned the potential extension of slavery in the Southwest, the now-worldly Melville scorned the temper of the time for its proneness to fantasy. “Nothing is talked of but the ‘Halls of the Montezumas.’ And to hear folks prate about these purely figurative apartments one would suppose that they were another Versailles where our democratic rabble meant to ‘make a night of it’ ere long.” Melville more soberly worried that the adventure might involve the United States in war with one of the “great powers”—England, in particular—a struggle compared with which “the Battle of Monmouth will be thought child’s play.”

In none of his complaint about the passions of “the democracy” did Melville abandon the principles of the American regime itself, as articulated by the Founders—quite the contrary. A few years later, he wrote that he wished Shakespeare were alive now, in New York City. “For I hold it a verity that even Shakespeare was not a frank man to the uttermost,” needing to guard some of his thoughts in the dangerous political atmosphere of Elizabethan England, where Protestant and Catholic factions maneuvered for dominance and civil war threatened. “And indeed, who, in this intolerant Universe is, or can be,” entirely frank? But, Melville continued, “the Declaration of Independence makes a difference.” America, the regime that guaranteed natural rights of life and liberty, secured by the constitutional rights of freedom of religion and of speech, would at least enable a reborn Shakespeare to be freer than he was in the old regime of monarchs and clerics.

But Young America loosened the tie between democratic self-rule and respect for natural and civil rights. One of its most celebrated members, Senator Douglas, would soon begin his public campaign for settling America’s western territories based on “popular sovereignty”—which, in practice, meant that settlers would vote slavery up or down, irrespective of the Declaration’s principles. By the time he published Moby-Dick in 1851, Melville had grown thoroughly disenchanted with Young American political bravura and equally skeptical of the optimism about democracy displayed by many in its literary-intellectual wing.

In the novel, we see all the characteristic types of persons dominated by a despot. Ahab is indeed a tyrant, effectively a usurper. The rightful owner of the whaling ship Pequod has hired a captain, not a monarch, and charged him with the task of hunting whales for their oil—but a mere contract in a commercial venture has no standing with an absolute ruler. Famously, Ahab has another mission, to which he has sworn himself and his sinister familiar, the mysterious Fedallah: to chase and kill the great white whale, the malevolent being that sheared off his leg during a previous voyage. None of his officers or crew has signed on for such a quest. Ahab will overawe and rule them by means of demagoguery, threats of force, and fraud, invoking, by turns, greed and terror.

Only two sane Americans on board have the intelligence to match wits with the insane tyrant. One is the narrator—“Call me Ishmael”—and the other the first mate, Starbuck. Neither has it in him to overthrow Ahab. Their failure shows why the third generation of Americans, or at least those calling themselves the Young Americans, lack the character to sustain their regime.

Ishmael, a former schoolmaster, informs us that he went to sea neither as a passenger (he had no money) nor as an officer. “I abominate all honorable respectable toils, trials, and tribulations of every kind whatsoever. It is quite as much as I can do to take care of myself.” He does do that, but meantime doesn’t mind being ruled by others on the ship. As a common sailor, he must obey orders. And doesn’t the New Testament tell us to accept our station in life, however menial? For that matter, “Who ain’t a slave?” Every human being gets thumped, “either in a physical or metaphysical” way. Metaphysical democracy or egalitarian thumping prevails over all; being itself pushes all of us around.

Having thus vindicated his honor—or, rather, excused his passivity under tyranny—Ishmael addresses the needs of the body. Unlike passengers, sailors get paid. The “urbane activity with which a man receives money” shows up either the self-contradiction or the hypocrisy of many Christians, who profess to believe love of money the root of all evil. “Ah! how cheerfully we consign ourselves to perdition!” The sailor’s body benefits not only from the human artifact of money but also from “the wholesome exercise and pure air of the fore-castle deck”—benefits he gains to a greater degree than his ruler, standing as he does behind the forecastle deck. Does the putative ruler really rule us? Ishmael wonders. Just as the captain of the ship only supposes that he breathes fresh air, but instead breathes air already breathed by the sailors, “in much the same way do the commonalty lead their leaders in many other things, at the same time that the leaders little suspect it.” And finally, what rules them all, if not “the invisible police officer of the Fates”? They are the ones who “cajol[ed] me into the delusion that [going to sea] was a choice resulting from my own unbiased freewill and discriminating judgment.”

In explaining, and explaining away, his conduct with these rationalizations, Ishmael exemplifies what Tocqueville considered the individualism of democrats. Under conditions of social equality, individualism is anything but rugged. Pressured no longer from above, or “vertically,” by kings and aristocrats, democratic man succumbs to “horizontal” pressures from the opinions of the crowd around him. He resists by withdrawing into himself, isolating himself from his fellow citizens instead of banding together with them to get things done—by, for example, forming the civil associations that Tocqueville found so admirable in Americans of the second generation. By contrast, a substantial portion of third-generation democrats is content with a way of life that inclines them to drift along; their habit of passive nonresistance to their fellow democrats has prepared them to accept the arbitrary rule of the despot. Whatever this former schoolmaster taught his students, it wasn’t a civic education.

Melville places Ishmael’s self-portrait as a passive demi-citizen near the beginning of Moby-Dick. He reveals Starbuck’s weakness near the end, shortly before the shipwreck that will kill all but self-caring Ishmael. A violent storm tosses the ship. Dutiful Starbuck wishes that they would ride with the gale, toward home, instead of against it, toward Moby Dick. Ahab has other plans.

Though despotic, Ahab has a perverse sort of nobility. When lightning strikes the ship and sets the masts on fire, Ahab takes this not as a divine warning but as a manifestation of mindless chaos. He defies it. “In the midst of the personified impersonal”—that is, amid mindless forces deified by the pious—“a personality stands here.” As tyrant, he would make himself stronger than the chaos that birthed him, and if he proves weaker, he will die defiant. “A true child of fire, I breathe it back to thee.” He worships like an atheist, by rebelling.

With their small-fire souls, it’s no wonder that democrats can’t stand up to him. The last man who might is Starbuck, a Quaker Christian. When lightning strikes Ahab’s steel harpoon with “forked fire” like a “serpent’s tongue,” he warns the captain that “God, God is against thee.” Turn home “while we may,” he urges, on “a better voyage than this.” Starbuck’s words panic the surrounding crew, who raise “a half mutinous cry.” Immediately recognizing a nascent revolution, Ahab seizes his burning harpoon and waves it “like a torch among them; swearing to transfix with it the first sailor that but cast loose a rope’s end.” The threat of force stops them, giving him a chance to reinforce his rule with speech, reminding them of the oath he had commanded of them to hunt the white whale, an oath “as binding as mine,” encompassing “heart, soul, and body, lungs and life.” To these words, he adds a final action, blowing out the fire on the harpoon and roaring, “Thus I blow out the last fear!” For a soul like Ahab’s, the last fear is of God, but that isn’t the last fear in the souls of democrats. Quite the contrary: instead of overpowering the tyrant, the men, so threatened and so reminded, scatter in terror. Starbuck’s attempt to persuade Ahab and to rally “the many” has failed, overborne by a demagogue on fire with libido dominandi.

The typhoon passes, and the crew cheers and sets about to repair the ship, as ordered by the officers. The democracy responds to immediate success and failure. Except for Starbuck, “the few,” the officers, prove little better. Only Starbuck foresees the ultimate disaster to which Ahab directs the ship. Only Starbuck can now act to prevent it, and chance (or is it God?) gives him the opportunity. He goes belowdecks to report to Ahab on the repairs. Seeing the muskets on the gun rack, including one that Ahab had aimed at him during an earlier quarrel, “an evil thought” occurs, which he finds hard to suppress: Should he kill Ahab, as Ahab had been ready to kill him? The gun is already loaded.

How evil is that thought? “Shall this crazed old man be tamely suffered to drag a whole ship’s company down to doom with him,” he wonders, effectively murdering more than 30 men? Ahab is asleep, incapable of resisting. Neither reasoning nor remonstrance nor entreaty has swayed the tyrant; Starbuck has tried them all. Unreasoning, immoral, and unloving, the tyrant has demanded only “flat obedience to [his] own flat commands.” As for the vow—the oath that Ahab invoked—“Great God forbid!” that we make ourselves lesser Ahabs, Starbuck thinks. Ahab’s oath ignores the good of ship and crew. A king would rule for the good of his people; the tyrant rules for himself, reaching for an illusory grandeur against the universe and against the God whom Starbuck worships. Assenting to the oath with Ahab, officers and crew alike assent to an oath with Fedallah, a figure reminiscent of the Prince of Liars.

Was there no “lawful way” to proceed? There was not. Restrained, Ahab “would be more hideous than a caged tiger, then. I could not endure the sight; could not possibly fly his howlings; all comfort, sleep itself, inestimable reason would leave me on the long intolerable voyage.” Ahab would murder sleep, as Macbeth’s conscience did; an anti-conscience, Ahab was the monster that would put reason to sleep. There was no human law for Starbuck to obey or to fear, here on the open sea. “Is heaven a murderer when its lightning strikes a would-be murderer in his bed, tindering sheets and skin together?” Surely not: Starbuck might kill with impunity and also without moral hazard. With Ahab dead, Starbuck might see his wife—named Mary, for the mother of Jesus—and child again. Without Ahab dead, he will not. Personal, political, and familial morality alike command tyrannicide.

A revolutionary must step outside the law, even if only to reestablish the rule of law. Starbuck then appeals to the final authority, praying: “Great God, where art Thou? Shall I? shall I?” Nowhere in this vast novel does God speak. Events occur, which might be interpreted as providential, but God is always silent. Here, only Ahab speaks, in his unreasoning sleep. Characteristically, he utters a command: “Stern all! Oh Moby Dick, I clutch thy heart at last!” It was “as if Starbuck’s voice,” dialoguing with himself and his God, “had caused the long dumb dream to speak.” Hearing Ahab’s dream-muttering, “Starbuck seemed wrestling with an angel.” Unlike Jacob, he lets go. “He placed the death-tube in its rack, and left the place.”

Returning to the deck, Starbuck tells Stubb to wake Ahab and make the report, prevaricating that “I must see to the deck here.” His conscience has made a coward of him. There will be no just coup d’état on this ship of state. The ship’s ruler will continue his defiant—indeed, insane—rebellion against the personified impersonal, while the ship’s potential ruler cannot bring himself to rebel against that rebel ruler.

Without a just revolution against him, the tyrant awakens, ascends to the deck, and sees the sunlight gleaming on the sea. Secure in his power, he exclaims megalomaniacally, “All ye nations before my prow, I bring the sun to ye!” The ship’s compass deranged by the lightning strike, Ahab takes charge of adjusting the ship’s course. Officers and men obey, “though some of [the sailors] lowly rumbled, their fear of Ahab was greater than their fear of Fate.” They choose the less wise fear. Ahab proclaims himself “lord of the level loadstone,” and overawes the “superstitious sailors” by making a new compass and gesticulating mysteriously over it, as if commanding it to come to life—adding fraud to force and demagoguery in his repertoire of despotic techniques. Ahab claims mastery over men by controlling the power of navigation over the chaos-sea. “In his fiery eyes of scorn and triumph, you then saw Ahab in all his fatal pride.”

And so the two men on board who can clearly see the tyrant for what he is fail to stop him. One man fails because a soft individualism pervades his soul. The other fails because a soft, pacifist form, or deformation, of Christianity guides him. If democracy can incline men to weak individualism, and if Christianity was the first widely accepted public expression of natural human equality—as Tocqueville writes—Melville issues a prophetic warning to Americans, showing how they might lose their republican civil liberty if they fail to understand, and stand up for, themselves under the laws of nature and of nature’s God.

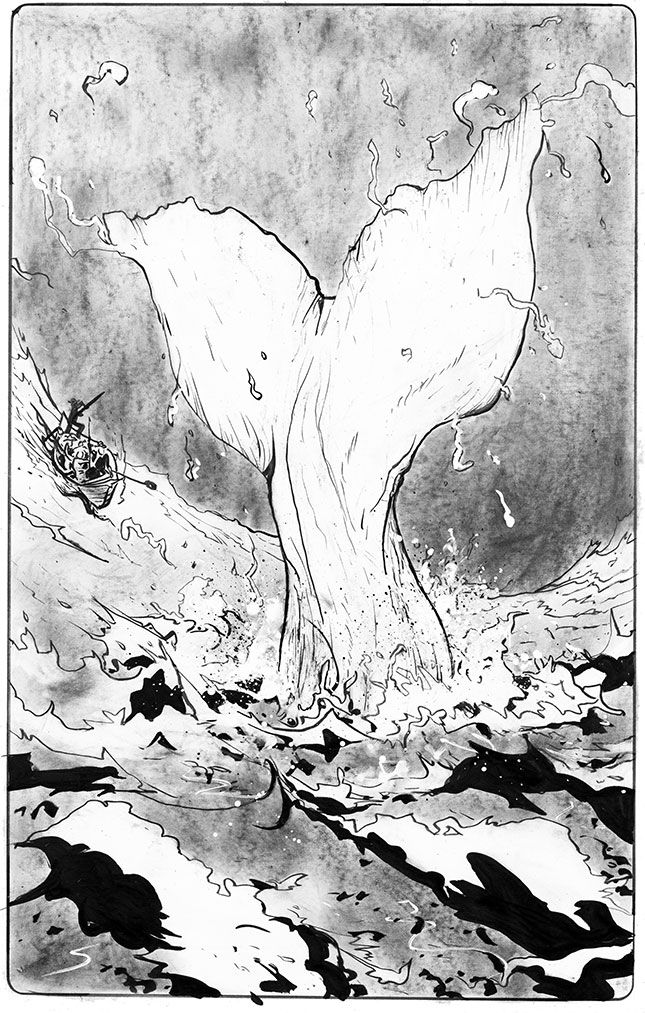

Illustrations by Paul Pope