Michael Gibson still remembers his first day working for Peter Thiel. Like many of Thiel’s hires, he’d met the contrarian investor through several of the PayPal founder’s variously eccentric political ventures. A onetime self-described “unemployed writer in L.A.,” who’d left a doctoral program in philosophy at Oxford, Gibson had met Thiel through his work at the Seasteading Institute, a Thiel-funded attempt to create a libertarian “floating city” in international waters. Then Thiel asked him to help teach a class at Stanford Law School on philosophy, technology, and politics. And then Thiel asked him to work for his hedge fund. Gibson had no intention of working in finance, or any experience in doing so, but he and Thiel had, he felt, “gelled philosophically,” sharing an interest in social thinkers and scholars of religion like Émile Durkheim and René Girard, as well as a commitment to what Gibson called “liberating people” from socially conditioned ideas.

Some opportunities you just don’t pass up. “I show up to work my first day,” Gibson says: September 27, 2010. “It’s a hedge fund, just as you might imagine on TV—there’s a ticker tape going around the room, a trading desk, lots of screens with Bloomberg Terminals. And I’m sitting there and I’m thinking—how did I end up here?”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

It took only a few hours for Gibson’s life to change. A colleague, he remembers, showed up at his desk and told him: “Oh, on the plane ride back from New York last night we came up with this idea. We’re going to call it the anti-Rhodes Scholarship,” a reference to the prestigious 118-year-old scholarship program that brings young scholars from across the former British Empire to study for free at the University of Oxford. “We’re going to pay people to leave school and work on things.”

There was no time to waste. The annual TechCrunch Disrupt conference was starting that day. Thiel was scheduled to speak. Thiel’s staff was keen to burnish his image—Aaron Sorkin’s blockbuster account of the creation of Facebook, The Social Network, was slated to be released soon; early leaked copies of the script had suggested that Thiel, a major early investor in the company, wasn’t particularly sympathetically portrayed. “He wanted to get a jump on that with some good news,” Gibson explained. “So we went to his house, we got into a car, and we went to this conference. And on the fly, we’re coming up with—okay, well, what do we call this thing? How much money? How many years?”

By the time Thiel was backstage, Gibson recalls, they were still discussing specifics. “Then Peter’s on stage, being interviewed and talking about this program as if it already exists, in the present tense.” The Thiel Fellowship would be a kind of “20 under 20” for the tech industry’s incipient disrupters. Twenty entrepreneurs under 20 would get $100,000 to drop out of college and work full-time on their startup ideas. There was no indication, during his interview with TechCrunch’s Sarah Lacey, that the idea had been developed only that day.

Thus is life in the orbit of Peter Thiel. With a net worth of approximately $2.3 billion, Thiel is far from the wealthiest person in Silicon Valley (Google’s Larry Page’s net worth is an estimated $66 billion, for instance). He may, however, be the most influential. Alongside his investments in high-profile companies like Airbnb, LinkedIn, Elon Musk’s SpaceX, and health-insurance company Oscar, Thiel’s more esoteric pet projects and funding recipients include some of the Bay Area’s most out-of-the-box libertarian-utopian ventures: the Seasteading Institute, the Eliezer Yudkowsky–helmed Machine Intelligence Research Center, which researches how to counter the threat of an intelligent Artificial Intelligence; the Center for Applied Rationality, a de facto headquarters for the Silicon Valley rationalist community; the Methuselah Mouse Prize, which funds antiaging research under the aegis of controversial gerontologist Aubrey de Grey. Thiel’s foundations have funded gleefully contrarian events like “Hereticon,” originally scheduled for May 2020 in New Orleans but since postponed, due to the coronavirus. It is billed as “a safe space for people who don’t feel safe in safe spaces.” And they’ve founded, too, novel medical apps like Carbyne, an Israeli “self-surveillance” 911 tool now used in New Orleans as part of the city’s Covid-19 public-health effort. Add the spectacular collapse of Gawker Media—bankrupted after a Thiel-funded lawsuit by former wrestling star Hulk Hogan, whose private sex tapes the site had posted in 2012—and the election of Donald Trump, to whose 2016 campaign he donated $1.25 million, and a pattern emerges. Wherever there’s a major shift in the American landscape in the past half-decade—be it political or cultural—there, somewhere on the donor list of the political campaign, or among the investors in the controversial technology, is Peter Thiel.

At first glance, the Thiel Fellowship is hardly as contrarian as, say, trying to end death. Since its first “class” was announced in 2011, the fellowship has funded between 20 and 30 promising young entrepreneurs annually. Past Thiel Fellows have created smash hits like Workflow—a productivity tool that, following its 2014 launch, was the Apple Store’s most downloaded app—and successful startups like Ethereum, the cyrpto-currency started by Thiel fellow Vitalik Buterin, and Figma, a design tool built by Dylan Field. Gibson and former fellowship director Danielle Strachman have since left the initiative to start the Thiel-backed 1517 Fund: a seed-stage venture-capital firm that backs the companies of several former Thiel Fellows. The relationship goes both ways: plenty of 1517 funding recipients have later become Thiel Fellows.

Yet the Thiel Fellowship is, on closer inspection, radically subversive—as much an attempt at delegitimizing the contemporary American educational landscape as it is about rewarding young would-be founders. The American collegiate system, Thiel, his staff, and his fellows unanimously affirm, has become a giant scam, transforming potential innovators into subservient drones; indoctrinating the disrupters of tomorrow into Marxist myths of resentment; and using the social-justice buzzwords of class privilege and structural oppression to crush the spirit. Like American progressivism, they say, the university is rotten from the inside out, on this view—and it needs to be burned to the ground, figuratively speaking, so that something new and better can be built from the ashes.

“The American collegiate system, Thiel, his staff, and his fellows affirm, has become a giant scam.”

The college-to-workplace model is also expensive and time-consuming, and it doesn’t reflect the dramatic changes in educational technology that make information accessible to anyone with a smartphone. Strachman compares the current state of such technology to earlier advances in transportation. “If you were gonna walk across the states, that would take a long period of time,” she observes. “But then with the invention of high-speed rail, let’s say, you can move orders of magnitude faster. So now, likewise, if I’m a young person today and I have a laptop, I can move so much faster than I could even when I was going to school, you know, 20 years ago. The opportunity cost for young people is that much higher. If they have this burning desire to do something right now and they can get started on it, why would you wait four years of a long slow process when you can just start in your dorm room right now?”

The very skills and values that Gibson and Strachman see college as currently rewarding—diligently completing assignments, checking off requirements, and producing work to a narrow set of specifications—run counter to those that the Thiel Foundation emphasizes. One of the biggest early predictors of failure in selecting Thiel Fellows, notes Strachman, was whether a candidate had received an Intel Science Award—a prize for high schoolers often considered catnip to prestigious colleges. “Anyone we met who won that did not seem to fare well in the wild,” she says. “There’s a difference between striving to gain accomplishments within an existing institution where all the parameters are set and transparent and known, where people are giving you commands about what to study and testing you on it, and building companies from scratch, which requires a whole different type of character and set of skills.”

When you’re in a university, Gibson and Strachman tell me, you usually learn to think in a conformist way. “The medium is a message,” says Gibson. “No matter what you do, if you have people acting obediently and taking orders over 16-plus years, that’s going to produce a certain type of person no matter what you teach.” Further, he adds, “it’s striking just how biased and far-left universities have become.” Universities talk about “diversity as a value,” Gibson says, but in practice, he believes, they reinforce a strikingly uniform worldview, in which “all of us are to some degree the victims of forces beyond our control, individual initiative is overrated, and history is a long list of grievances [and] of moral atrocities.”

The Thiel Fellowship’s politics may not have trickled down to its recipients, but its fundamental ethos of what you might call Thielism—the idea that human progress is driven by the creativity and bravery of a few and stymied by ossified ways of doing things—is ubiquitous among current and former fellows and permeates many of their startups.

Take Stacey Ferreira, a 2015 fellow. The fellowship was hardly Ferreira’s entrée into the world of tech—like many fellows, she’d been successful on the startup circuit long before filling out her application. She’d started her first company, a password-storing site called MySocialCloud, while still in high school, and sold it to Reputation.com in 2013. By 2015, when she started the Thiel program, she’d already coauthored a book on the future of work, 2 Billion Under 20: How Millennials Are Breaking Down Age Barriers and Changing the World, with fellow entrepreneur Jared Kleinert (Thiel right-hand-man Blake Masters wrote the foreword). Her current project, founded during her fellowship, is an app called Forge that enables firms to schedule shift workers, bringing the flexibility and location independence of laptop workers to what she calls “blue-collar space.”

The original version of Forge, Ferreira admits, was probably too idealistic: trying to pair workers with companies where they hadn’t yet received any formal training. “I learned very, very quickly that [people] like you and me might be super-capable people, but we’re not going to be able to walk back behind a Starbucks counter and know how to make a caramel macchiato for someone right now.” Companies like Starbucks can still use the app to schedule trained workers. Ferreira’s ultimate goal, though, is to automate training—allowing workers to prepare for jobs without excessive bureaucracy intruding. “I still would love to live in a world where I could maybe download an app, watch some training videos, and then go do it,” she muses. “But I think we’re still a little bit further away from a content perspective.” She wants to change the “mentalities” of businesses, telling them: “Hey, the future is coming and it’s time that we do something about it.”

A Beirut-born former fellow, also from the class of 2015, James Kawas is the founder and CEO of a startup called Saily, which has developed a marketplace app letting people buy and sell items locally. Like Ferreira, Kawas was making—and selling—companies long before the Thiel Fellowship. And, again like Ferreira, he envisions the startup model as an integral part of human flourishing and freedom. People learn, he insists, by doing—not simply by listening to proponents of disembodied knowledge, or by accepting the authority of people with no “skin in the game,” such as professors “disconnected from reality.” After all, he says, he learned to code on his own in high school, utilizing online resources.

He tells me about a friend’s tech firm, Touch Surgery, through which would-be doctors can hone their skills virtually. “You run surgeries, and you’ll learn how to do surgery. You can play through a surgery 1,520 times, and you’ll know how to operate.” Sure, he caveats, you won’t be as good with medical scissors as you would be if you trained in-person at a medical school. “But people will be shocked by how much you can understand supposedly complex things just by looking at them.”

Kawas, too, lauds the Thiel Fellowship as a mechanism for countering the “dirty game” of the American educational establishment. Colleges “force their thoughts” on you, he says—they’re “breeding grounds for advocacy.” They “ruin you as a person.” And, worst of all, they teach you that life isn’t something that you can control. “Accepting yourself as you are is not improving yourself,” Kawas insists. He characterizes the “extreme leftism” of the university as a form of fatalism: assuming that the world cannot change in substantive, even miraculous-seeming ways, through the efforts of a few brilliant, even miraculous-seeming, people.

For the most part, the fellows deny that Thiel—whom most refer to just as “Peter”—has any formal influence on their thinking. They characterize him as a kind of nebulously supportive benefactor: someone who will have breakfast with them a few times, and give them feedback on their latest startup ideas, but who gives them the space and time to develop their own practical—and ideological—commitments. But the specific brand of utopianism that the Thiel Fellowship’s staff and recipients espouse is indebted, implicitly and sometimes explicitly, to Thiel’s writings, and particularly to his idiosyncratic—theologians might say heretical—vision of Christianity, mediated by the work of French philosopher René Girard: a distinct fusion of techno-utopianism that characterizes its successes as Christian miracles.

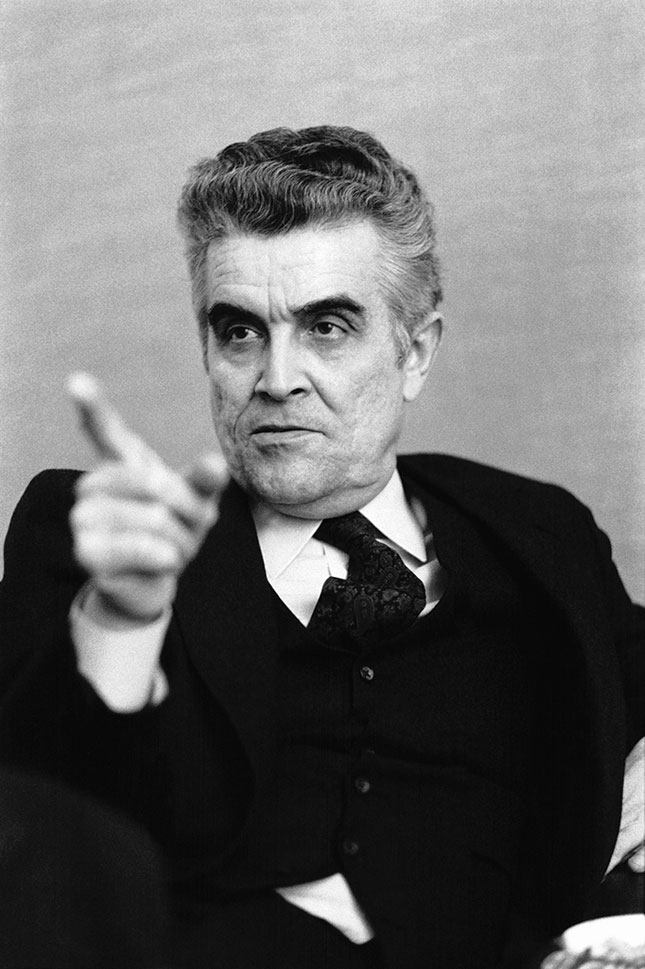

Unlike, say, Ayn Rand, René Noël Théophile Girard (1923–2015) is not an obvious choice to be a philosophical titan of the tech world. A historian and literary critic with a fervent commitment to Christianity and to Christian ethics, Girard was, until recently, a relatively esoteric figure, his works more often referenced on postgraduate philosophy syllabi than in TED Talks. But for Thiel, who studied under Girard at Stanford, the philosopher provides the key to understanding not just Christian metaphysics but also how human beings interact.

Girard’s theory of the scapegoat and his related notion of mimesis are at the core of Thiel’s interest. Simply put, Girard holds that human desire is rooted in an obsessive form of imitation. We want not what we should want, but what we see others as having, and thus deem “worthy.” Human relations are fundamentally predicated on this mimetic desire, which can lead us to harm one another in rivalrous conflict. We resent those who have what we think we want—but we want what we do because those whom we resent have it.

Societies deal with these inherently chaotic impulses by creating mythic and sacred narratives of legitimate violence, which identify a scapegoat: a chosen, if actually innocent, target for this complex system of violence and desire. The scapegoat is ceremonially purged from the community, often through literal violence, allowing the community to think of itself as blameless, and to expunge its violent desires. Christ, in Girard’s view, is the ultimate scapegoat, whose blameless sacrifice functions as revelation, exposing the truth of the scapegoat mechanism: that its victim is innocent and that communal sacrifice is a lie.

Thiel and what you might call Thielism—the implicit worldview that pervades both the fellowship and the investor’s wider political projects—map mimetic desire onto modern identity politics. Those who view the world as an oppressive system of privilege and oppression are driven by rivalrous resentment.

Thiel’s best-selling business book Zero to One (coauthored with Blake Masters) is suffused with Girardian themes, though the philosopher is never mentioned by name. Indeed, the authors identify a major cause of business failure as the inability to see beyond the conflicts of mimetic desire. “Inside a firm,” they write, “people become obsessed with their competitors for career advancement. Then the firms themselves become obsessed with their competitors in the marketplace. Amid all the human drama, people lose sight of what matters and focus on their rivals instead. . . . Rivalry causes us to overemphasize old opportunities and slavishly copy what has worked in the past.”

This view, the authors suggest, should be understood in contraposition to a Marxist account of history, in which, “according to Marx, people fight because they are different.” Wrong, Thiel and Masters suggest: people are all the same. Or, at least, if they are not the same, it is because certain people are more capable of harnessing their intellectual potential. (That some people lack the natural intelligence or affinity for harnessing such potential goes unaddressed.)

The creation of a remarkable, cutting-edge company, for Thiel and Masters, shouldn’t just be about amassing personal wealth for its founders. It should also be about remaking the world—transforming personal potential into a technological reimagining of human life. By contrast, the stasis of mimesis, driven by human resentment, leads to political mediocrity and technological anhedonia. To disrupt, insofar as it means to disrupt the mimetic system, is thus a liberating act.

And when radical human potential is unleashed upon the world, it demands—and deserves—proliferation. Thiel and Masters justify monopolies, so long as the company is creating genuinely new, life-improving technologies to earn its outsize profits. “Monopolies deserve their bad reputation—but only in a world where nothing changes,” the authors observe. “In a static world, a monopolist is just a rent collector. If you corner the market for something you can jack up the price . . . but the world we live in is dynamic: it’s possible to invent new and better things. Creative monopolists give customers more choices by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world. Creative monopolies aren’t just good for the rest of society; they’re powerful engines for making it better.”

In a 2007 essay published in an otherwise obscure Michigan State University Press anthology titled Politics and Apocalypse, Thiel characterizes contemporary Western civilization as experiencing a permanent crisis, since the illusion of the scapegoat has been exposed. The center cannot, and will not, hold. “The unveiling of the mythical past,” Thiel writes, “opens towards a future in which we no longer believe in any of the myths. . . . [T]heir unraveling may deprive humanity of the efficacious functioning of the limited and sacred violence it needed to protect itself from unlimited and desacralized violence.”

“The creation of a cutting-edge company, for Thiel and Masters, should be about remaking the world.”

In such a context, according to the tenets of Thielism, creativity means thinking outside the bounds and strictures of failed institutions, including academic credentials, freeing us from resentment, and opening new paths of progress, technology, and positive change. (Thiel’s own contribution to the anthology falls well within Thielist antiestablishment principles. He is the only contributor without a substantial academic background; he did, however, fund the 2004 conference on Girard from which the book’s essays are drawn.)

For Kawas, Thiel’s economic and social vision borders on the mystic. “The real meaning of zero to one,” Kawas says, “is to make something new . . . the idea that we’re not stuck in the past. We can make something new from nothing . . . [and] that changes the nature of reality.” When resentful people see the world as a zero-sum place, they start redistributing assets, assigning guilt and blame to scapegoats. Instead, Kawas explains, “You can do magic. You can do tech.” This is, he insists, a “deeply Christian idea.” (Thiel himself has frequently publicly identified as Christian, though it’s worth noting that there is no Christian tradition in which the provenance of creating out of nothing—ex nihilo—is not understood as the specific and unique prerogative of God, rather than a right afforded to human beings.) It “rejects the blame” that comes from the erroneous belief that there’s “no way to change the reality.”

Thus, techno-capitalism-as-miracle: the notion that a few brilliant individuals can radically reshape the limits of human reality, which are revealed to be in part the product of intellectual sluggishness and moral fear. Thielism is the belief that a human being can—on his way, say, to a San Francisco speakers’ panel—conjure an idea for reshaping prestigious education in America. Old things must pass away, one way or another.

Kawas asks me if I know the biblical verse—a loose paraphrase of Matthew 5:23—about how the kingdom of God falls on both the good and the evil. “Truly, when you do the right thing, everybody benefits. Which is very similar.” Sure, Kawas says, the social-justice warriors, the “leftists,” may carp. They may call Thiel an evil genius, a puppet master for modern illiberalism. After all, he points out, Thiel had to leave San Francisco back in 2018 for Los Angeles, to get away from all the progressives who want to blame him for their problems.

“Peter,” Kawas concludes, is one of the “very few humanist people” in the world. “He believes that we can do a lot. We can afford not to die. We can go to other planets. We can make new countries. We can cure cancer. We can fix violence. And he’s not a romantic about it. . . . The guy is really—if you look at his actions, his beliefs, they’re just so insane. But he’s extremely intentional about everything he ever does. Most [people] don’t understand. Which does him a good service—because he’s always running conspiracies to change the world. And the best thing you can get for someone running conspiracies is for people not to understand what he’s doing.”

He sighs. “But you have to be scapegoated,” he says.

Top Illustration by Garry Brown