Tolkien: Maker of Middle Earth, The Morgan Library & Museum, through May 12, 2019

Tolkien: Maker of Middle Earth is the new show at The Morgan Library in Manhattan. It’s a charming tribute to J.R.R Tolkien (1892‒1973), the Oxford professor best known for writing The Hobbit, in 1937, and The Lord of the Rings, the high-fantasy novels published in three volumes in 1954 and 1955. The Lord of the Rings, in which Tolkien constructed an astonishing and elaborate world of heroes, villains, adventure, pursuit, and peril, is one of English literature’s most widely read novels.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The show is a fan letter to Tolkien from the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford, which organized it, and delivered by the Morgan Library in its characteristically elegant way. It’s mostly memorabilia, including photographs and manuscripts, with some of Tolkien’s illustrations, many having made their way into the books. My only complaint about the show was that the galleries were too small. There are lots of bits of paper needing more room.

It’s a biographical show. That’s its stated goal, and it’s not for me to insist on something different. The project does what it says it will do, which is to tell us about Tolkien. I learned some good, new things about him but nothing shattering or even provocative. He was the orphan of a bank-manager father, based in South Africa, who died when he was four, and a middle-class English mother who died when he was 12. His guardian was a Roman Catholic priest, who advanced Tolkien’s immersion in Catholicism and guided him toward an Oxford education specializing in English. He married his high school sweetheart, to whom he remained devoted until her death in 1971, had four happy children, and taught at Oxford until his retirement in 1959. He fought at the Somme in 1916, lost most of his Oxford peers to combat, and left the war with trench fever, from which it took years to recover. Tolkien was respected as a scholar and teacher and a mainstay of the Oxford faculty. He was a close friend and kindred spirit of C.S. Lewis. He was also a savant who created imaginary languages when he was a child, later developing stories around them, inspired by Norse mythology, to entertain his own children in the 1920s. These stories became the basis for his books.

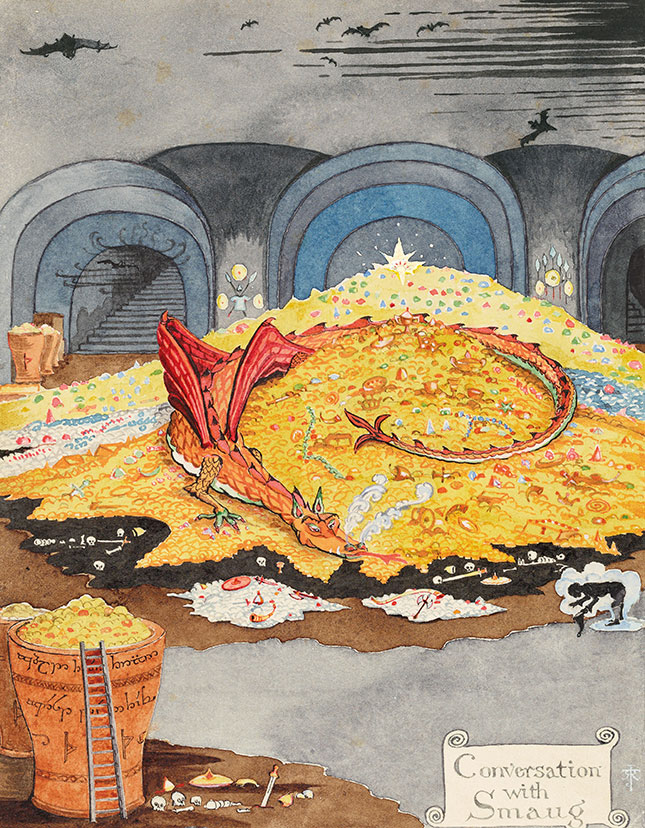

He was a fine artist, too, coming from a class background where men and women learned to observe the world through drawing. His talent went well beyond aesthetic pleasure or mere accomplishment. His elaborate Christmastime letters to his children, filled with fictional characters and lavishly illustrated, make him a dad after everyone’s heart. These letters; his original illustrations for The Hobbit, which were part of the English edition; his designs for book jackets; and his maps for the fictional worlds he created are in the show. His aesthetic is lovely—Art Nouveau easing into Art Deco—and austere and spooky.

The show explicitly bars not only the critical reception of Tolkien’s work but also how it fared in its recent movie versions. It’s as reserved as Tolkien himself. He barely spoke about his horrible time in battle, though both wars informed his work. He spoke little about losing his parents, aside from saying that he loved and missed them deeply. His is the stiffest of upper lips, and, partly because of this, the show has the whiff of hagiography. There are lots of relics—his office furniture, his academic robes, his date book—and lots of nice family photographs. The tensest moments, and they’re not really tense, surround disagreements over book-jacket designs.

It’s not a boring show. It’s something I’d expect from a keeper of the flame, and the curators are archivists at the Bodleian. When I read the catalogue, though, I was startled by W.H. Auden’s observation from the 1950s about The Lord of the Rings. Auden loved the books and admired Tolkien, who taught him at Oxford. He wrote that he could “rarely remember a book about which I have had such violent arguments.” The show produces fan mail from Iris Murdoch, Joni Mitchell, C.S. Lewis (with whom Tolkien taught), and others, but Auden tells us that many of his literary friends hated it. Why?

It takes only a little reading between the lines. Tolkien was a deeply observant and thoughtful Roman Catholic. In The Lord of the Rings, he created a world suffused with spiritual belief, a Little England, with menace gathering on all sides. He wrote it during the Second World War and the Cold War. He hated day-to-day politics but had political views that were monarchist, hierarchical, and Tory—philosophically what we might call Burkean. His mythic world was about as far as possible from that of the Angry Young Men of British avant-garde culture in the late 1950s and early-1960s. The books don’t give us pure and unadulterated evildoers. There are no Hitlers, and nary a Pol Pot, or even a humdrum Idi Amin. Evil in Tolkien’s world springs from abuse of power, a far more insidious, nuanced, and toxic brew, because those drunk on power often start with the noblest intentions.

On the one hand, Tolkien was surprised in the 1960s to learn that The Lord of the Rings had a big hippie following via its aversion to centralization, authoritarianism, materialism, technology, and plutocracy. On the other, hobbit society was hardly diverse or “woke.” It’s the antithesis of Cool Britannia. The Shire, where hobbits live, surely would have voted “Leave” on Brexit. I think the Bodleian, or the Morgan Library, should look at Tolkien’s legacy and critical reception one day. Auden found the disagreements about his themes sharp, and I imagine that they were subtle, too. The Lord of the Rings goes from crisis to crisis, with its heroes reeling from battles, evil deeds, traps galore, and a gamut of misshapen allies and villains. The iron fists sometimes come in velvet gloves. That it ends with a returning hero simply saying, “Well, I’m back” is the zenith of understatement. The Morgan’s show is good, but leaving well enough alone is no way to end a story.

Top Photo: J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973), Dust jacket design for The Hobbit, April 1937, pencil, black ink, watercolor, gouache. Bodleian Libraries, MS. Tolkien Drawings 32. © The Tolkien Estate Limited 1937.