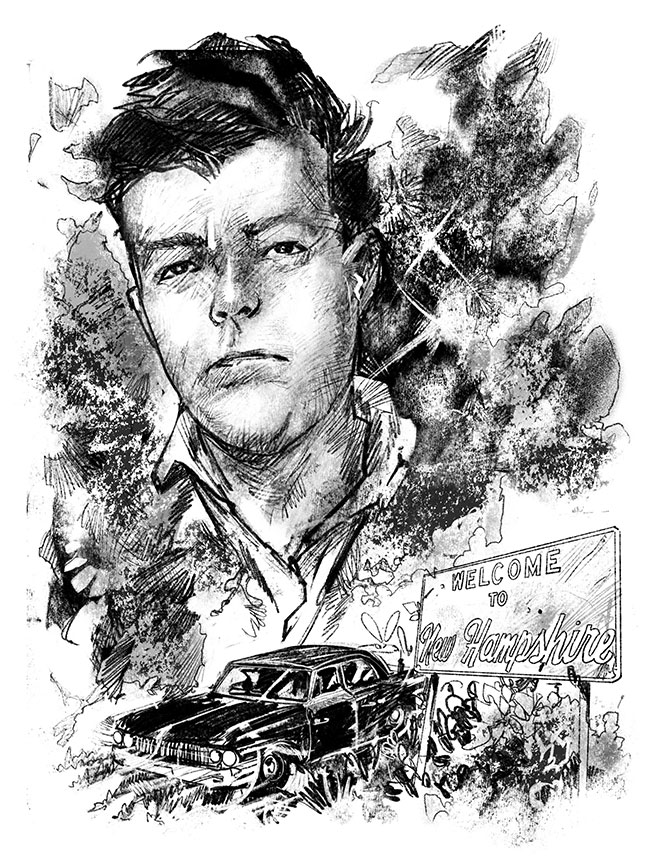

How’d you find me?” It was Ash Wednesday when I cold-called John “Maxie” Shackelford’s house in Manchester, New Hampshire. It’d been 56 years since he left Boston, the city of his birth, and he hadn’t left for the reason most do—to save that buck Taxachusetts takes out of your pocket whenever you go to a bakery. Maxie left under duress. He was handcuffed in the backseat of an unmarked car with an FBI agent sitting beside him and a police escort, blue lights flashing.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

When he crossed the northern border on I-95, a sign whizzed past the window. It didn’t say “Live free or die” in 1965. It said, “Welcome to New Hampshire.”

Maxie never looked back.

Boston police said he was marked for death. He was caught up in a gangland quarrel that quickly degenerated into a war, pitting the McLaughlin brothers of Boston’s Charlestown neighborhood against Buddy McLean and his friends from the neighboring city of Somerville. Each side was trying to eradicate the other, and by the time Maxie was transported north, they were well on their way to doing exactly that. Bodies were left slumped in cars, dumped in Boston Harbor, sprawled on the street, and left in patches of woods for critters to eat. Number of cases solved? Zero.

Maxie was one of the reasons why. Questioned by police as a matter of routine in those days, his answer was always the same—“I have no idea.” Maxie, those guns we know you got, where are they? “What guns? I have no idea.” Who was with you in the car that got shot up? “What car? I have no idea.” Gangsters dying like dogs in the street after an ambush were more likely to spit in the eye of their interrogator than spill the beans, even as God’s judgment barreled toward them.

This code of silence was especially strong wherever the Irish Catholic influence, forged over centuries of English oppression, ran deep. It was a cultural artifact passed down through generations of poor land-bound families that had little else besides kinship, friendship, and self-respect. When authorities came knocking, it was their only means of resistance. It soon defined them.

Irish silence crossed the Atlantic with the throngs of poor immigrants in the nineteenth century and nestled in their collective psyche right through the twentieth. It was strongest in Irish enclaves like Charlestown, where keeping one’s mouth shut was a commandment nearly as authoritative as the Ten those nuns forced Maxie to learn at Saint Catherine of Siena’s, and its enforcement didn’t wait for the afterlife—it was as abrupt as a backhand. The police in the Bunker Hill district could only shake their heads. Whenever they descended on a bar where shots were fired, they’d find lit cigarettes, half-empty bottles, and a breeze because the back door was left open. The only body was on the floor. “Police said there were no witnesses to the shooting,” the next morning’s newspapers would read, “and the night bartender was out.” The truth was, there were plenty of witnesses until the night bartender hollered, “Everybody out! No witnesses!”

The silence then has a hangover today. It’s in the hazy and confused versions of what happened during Boston’s Gangland War of the 1960s—versions that have to be questioned because they’re usually based on double hearsay and the testimony of informants offered prosecutorial immunity for their story—or a story. Many of those directly involved never made it to 1970.

Maxie is a rarity: a survivor who kept his mouth shut.

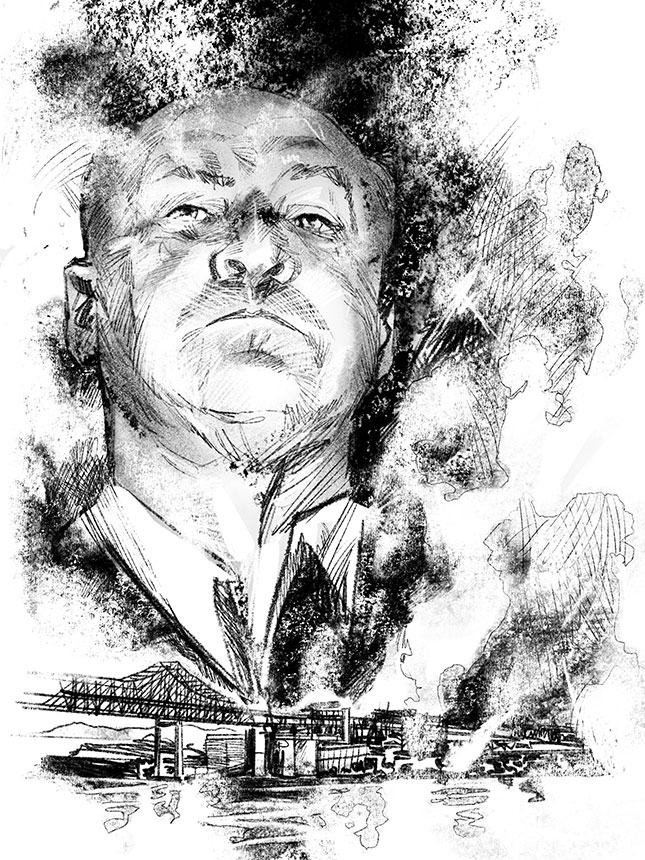

There are others who stayed neutral during the war, who worked on the docks and moved easily in the underworld. Some are opening up. They’ll tell you that the friction between Charlestown and Somerville went back to the 1950s, when the McLaughlin brothers—Punchy, Bernie, and Georgie—aligned themselves with a crew from New York and tried to take over Boston’s waterfront rackets. Rough characters from Somerville joined South Boston to resist the invaders, and New York never could get traction in unruly Boston. The McLaughlin brothers, their ambitions dashed, recoiled back to their stronghold in the Charlestown Navy Yard.

What followed was a Budweiser truce. Dangerous men from both sides of the argument started drinking together at the Celtic Tavern, one of 50 or so bars profitably established in the square mile that was Charlestown. The McLaughlins were there, as were their partners, a grim-hearted pair of brothers by the name of Hughes. It was their turf. It was also on the border of Somerville, and Buddy McLean would come over from that city’s Winter Hill neighborhood to hoist a few dozen. McLean, a loan shark who also worked as a checker on the waterfront, was a backslapping, popular fellow who was rarely alone. Joe McDonald was among those walking in with him; “Joe Mac” was a mysterious underworld figure already in his forties by the late 1950s. No one was bumping him at the bar.

Maxie remembers the scene: teamsters, townies, sailors, loan sharks, and killers with callused hands all mixing together; the acrid smell of sweat and stale beer, the smoke hanging over everyone’s head like a storm cloud. He’d sit on a stool alongside Stevie Hughes, who was always angling to save his dollar and relieve you of yours; and Connie Hughes, who hoisted more than he should have because of an unhappy marriage. Maxie didn’t need a reason to hoist. “Thirty beers was nothing to me,” he said. “Scotch was nothing to me.”

The McLaughlins and McLean laughed and swore and slurred toasts to their shared heritage right up until that night things went bad at Salisbury Beach.

It was Labor Day weekend, 1961. Georgie McLaughlin, stewed to the gills, insulted and likely assaulted the girlfriend of one of McLean’s many friends. What happened next was the mandatory minimum for that kind of conduct in that kind of crowd. Georgie was beaten senseless and ended up in a hospital. Predictably, his two brothers sought vengeance—they crossed the border into Somerville and demanded that McLean hand over those responsible. McLean knew what that meant. He refused.

Eight weeks later, Georgie was out of the hospital and among those attaching dynamite under the McLean family car. “Buddy was up in the window having a drink,” Georgie told Maxie the next day. “He heard us in the dark and started shooting.” They ran like jackrabbits. The dynamite wasn’t attached properly and never blew up. Buddy did; he blew his top.

Two days later, he and two accomplices crossed the border into Charlestown and headed for City Square. They knew that Bernie McLaughlin would be in his usual spot out front of Richard’s Liquor Mart collecting loan-shark debts. The sun was high in the sky when McLean stepped out from behind a steel abutment under the Mystic River Bridge and shot him dead—and then shot him a few more times. More than a hundred longshoremen on lunch break watched—but no one saw a thing.

The storm cloud over everyone’s head didn’t break. What followed instead were distractions. In 1962, the Boston Strangler began terrorizing every wife and widow, and then the city itself donned a black veil on November 22, 1963, when John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. The relative peace in gangland was a false peace. Buddy had been sent to prison on other charges by a judge with ears on the street. Stevie Hughes was in stir for shooting and stabbing someone on the docks. Joe Mac was locked up in 1961 for armed robbery, looking at ten years. Georgie was a wanted man after committing murder at a christening party, of all places, and was lying low. He had a wad of cash; Maxie had an aggravated assault charge over his head. So they paired up and fled the state.

To a townie like Maxie, being on the lam was like seeing the world. “Me and Georgie traveled all over the country,” he told me, though the adventure very nearly ended early. Maxie was speeding, and they were pulled over by a sheriff in some hick town he can’t recall anymore. Interstate flight to avoid prosecution brought the FBI in, and when they were tossed into the local jailhouse, Maxie was bleeding in his shoes. “I thought that was it, but we only had to pay a fine.” When he got back behind the wheel, Georgie looked at him. “Don’t drive fast anymore,” he said. They continued on, making frequent stops at drugstores for Georgie to steal Visine drops, which he used all day for a bad eye, and eventually made it to Oregon, where they played shuffleboard in bars with a couple of girls they’d met. From there, they swung down to California and then to Mexico. They headed straight for a cantina, and Georgie grabbed a house girl and headed straight for the stairs. When he refused to pay, the bartender pulled a gun. Georgie and his bad eye didn’t blink. He turned on all the gas jets and stood there with a lighter and said, “Lemme know when.”

“I thought that was really it,” said Maxie.

Things were getting hot. Then the money ran out, and they split up. Georgie took a train back to Boston. He hid out in a rented house until the afternoon when Boston police detectives and the FBI kicked the door in and found him upstairs in his skivvies. They dragged him kicking and screaming to the Charles Street Jail. He was out of circulation indefinitely.

But there were a thousand Georgie McLaughlins in and around Boston at that time, guys who had long since unmoored themselves from their nun-drilled Catholic compunctions, who wanted only to make a buck and didn’t much care how. Maxie was among them.

When I was a boy, my parents sent me to Saint Catherine’s parish school, but I kept getting kept back,” he said. As he neared 12 years old in the third grade, his mother finally pulled him out and put him in public school. “Oh, I was a sonofabitch. I didn’t like school.” He didn’t like Mass, either. “I skipped that, too, and lied to my mother.” His yearnings went no higher to heaven than the doughnut-shop window on Monument Street. He’d press his nose up against it, dreamily watching the baker dust rows of doughnuts with cinnamon sugar or glaze them with chocolate goodness, and him without a nickel in his pocket.

“I needed money. I was all about money. That’s why I hooked up with the Hughes brothers and the McLaughlins when I was a young man,” he said. “They had a big loan-sharking business. I saw them hanging around the Celtic Tavern and the Alibi Club at all hours, gabbing with different people. I was doing some longshoring but wanted to be Mr. Big, like them. I said, ‘Lemme see if I can make some money with these guys,’ and starting loan-sharking. Next thing I know, I’m on the lam with a hole in my pocket.”

In the summer of 1964, he returned to Boston. His timing could not have been worse. Antagonists on both sides were out of prison and on the street. Joe Mac escaped and had already amassed an arsenal. The storm cloud broke.

Between March and Thanksgiving of 1964, there were 15 unsolved gangland murders—two more than the 13 that ended the era of unlocked doors in Boston. Newspaper editors had a field day coming up with headlines: “GANG WAR DEATHS REPLACE STRANGLINGS AS HUB TERROR,” said one. “ORIGINAL BOSTON MASSACRE LOOKS LIKE CHURCH PICNIC,” said another. “MURDER-A-MONTH IN BEAN TOWN,” said the New York Daily News. “Not even Chicago’s Prohibition killings can match staid Boston’s corpse-of-the-month club.” Citizens started referring to the Boston Herald’s obituary section as “the Irish sports pages.”

“I got caught up in the war,” Maxie said.

Fourteen more gangland murders, also unsolved, were added to the ticking tally in 1965. The tenth was Punchy McLaughlin, the last of the McLaughlin brothers still at large. Somerville and its allies shot off half his jaw and his right hand in at least four ambushes before they got the rest of him on October 20. He was waiting for a bus to get to Georgie’s murder trial. And just like that, Charlestown was not only decimated but leaderless.

Maxie was standing in a crowded courtroom for Georgie’s trial and wondering what was keeping Punchy when someone came up behind him and said, “We’re getting you next.” He knew then that they could, and that Charlestown wasn’t going to defeat Somerville. “They had all the cops giving them intelligence on us,” he said. “They were too strong.”

The Hughes brothers knew it, too. They decided to give peace a chance. Maxie went with them when they drove up to Revere, neutral territory, in Connie’s car. “It was at the Ebb Tide Lounge. We wanted to settle things,” he said. “We sat there at a table drinking and listening to the band when Connie spotted some guys we didn’t want to see, all spread out. He saw a top mafioso from Providence nod to one of them and smelled a setup. ‘Let’s go,’ he said. ‘Something ain’t right.’ We got out of there.”

Maxie was a nervous wreck. “Every time I walked out my front door, I didn’t know if I was gonna live or die,” he said. One night, he was heading into his sister’s building in the projects and thought someone was behind the main door. “I had a .45 in my pocket and went for it but shot a hole through my topcoat,” he told me. “It was a nice topcoat, too. I thought, ‘What the hell am I doing?!’ ”

The Hughes brothers surrendered to rage and despair. They crossed the border into Somerville’s Winter Hill neighborhood and staked out the 318 Club. A few minutes after 1 AM on October 30, 1965, Buddy McLean came out and crossed Broadway. One of them stepped out from the shadows under the marquee of an abandoned theater with a shotgun and a nylon stocking covering his face. A blast tore part of McLean’s head off.

McLean’s heart didn’t stop beating for 30 hours. He died on Halloween—the fourth anniversary of the day he himself stepped out from the shadows under the Mystic River Bridge to kill Bernie McLaughlin. His Somerville and Southie friends never got over his death; some still mourn him today. It was like the death of JFK.

Maxie was on a score in Cape Cod when it happened. He rushed back to Charlestown and sought out Stevie and Connie. It took him a few days to find them. “It was Connie who shot Buddy,” he said. I raised an eyebrow. I’d always heard and read that it was Stevie who killed McLean. “I haven’t read any of the books. Connie told me it was him and he wouldn’t lie. Connie was the go-to guy. He always had shotguns, and he was always practicing in the woods. Stevie? He never practiced. Whoever shot Buddy and the two fellas with him was a damn good shot. That’s Connie.”

On a misty night two weeks after McLean’s funeral, a black sedan crossed the border into Charlestown and snaked its way through side streets, just north of the Bunker Hill Monument. It rolled past a white Chevrolet parked on the corner of Medford Street and O’Meara Court and then circled back toward it and erupted. Maxie was shot in the arm. The other passenger, identified in the Boston Globe as “another man who, with his brother, was closely associated with the McLaughlins,” was ready and started blasting back. It was Connie. Both cars roared through the streets and another gun battle erupted near Saint Catherine of Siena’s, the church of Maxie’s childhood. “Brakes were screaming and shots were fired from both cars,” said a civilian out walking his dog. “I was really scared. . . . It sounded like the Fourth of July.”

Maxie remembers that night like it was yesterday. “I was in the passenger seat. We were sitting outside my sister’s place in the projects when Connie saw them U-turning in the rearview mirror. ‘Get out of the car now and pull your gun out,’ he said. If he didn’t spot them, I’d be dead now. I reached over the roof to shoot and that’s when they got me in the arm.” The scar, a half-moon on his right forearm near his elbow, is still visible.

Maxie spent the night at Mass General under police guard. Detectives were in his room asking a lot of questions and got one answer: “I have no idea.” When he was discharged, a patrolman was assigned to walk out with him. Maxie, close to despair, told him he should turn back “because there’s no reason for both of us to die.” He recuperated at his sister’s. Connie called him while he was there.

“We gotta get back out there, Maxie. We gotta get them.”

“Connie, I’m laid up here.”

“Well, you can’t be laid up too long!”

That was the last time he heard Connie’s voice. When he went back to the hospital to get his stitches out, the cops were waiting for him with felony warrants from New Hampshire. He waived extradition and was driven up to his arraignment in Manchester District Court by the state police, with an FBI agent beside him. The charge was giving false information to purchase nine guns. “Don’t say that you transported any of them into Massachusetts in one piece,” the unnamed agent advised. “That’d get you about nine years per gun.” Maxie kept his mouth shut and was offered a deal for a guilty plea—seven months in the Valley Street Jail. “Take the deal,” the agent said.

On May 25, 1966, Connie was ambushed while driving along the Northeast Expressway. His car careened over the center strip and crashed into a concrete barrier. A few Good Samaritans ran over to the smoking wreck and pulled him out, but he was already gone. His brain was on the passenger seat.

Stevie fled the city. He drove up to New Hampshire and, using an alias, visited Maxie in jail. He wore diamond rings, which meant that he was going to hawk them for quick cash. “Stevie, I have no money,” Maxie told him. “Don’t worry about it. I’ll take care of you,” came the reply. But he didn’t, and that was the last time Maxie saw him.

Ever the hustler, Stevie hired himself out as a bodyguard for a bookie at $50 a day. In the early afternoon of September 23, 1966, he and the bookie were traveling along Route 114 in Middleton, a suburb 20 miles north of Boston. A sedan pulled alongside and shot both of them to pieces. The car crashed through several guardrails, went over an embankment and into a ditch. A man working nearby ran over to the bullet-riddled wreck to see bullet-riddled Stevie breathing his last. “He opened his mouth but couldn’t say anything,” he said. “He just shrugged.” In his pocket was his day’s pay—$50.

Holy Cross Cemetery in Malden has become the Celtic Tavern. The Hughes brothers are there, as are Bernie and Punchy McLaughlin, and Buddy McLean. They’re reunited under a well-trimmed lawn, their rage and despair only echoes in the breeze.

When Maxie got out of the Valley Street Jail in the summer of 1966, he had no desire to join them. He had nothing else either, not even a car. He wandered around Manchester like a lost soul until he got a job at Henry’s Auto Body on North Turner Street. He walked there and back every day, his route skirting a neighborhood with a name that made him duck—Somerville. The local police, on edge, would drive slowly behind him. “They didn’t want a gangland casualty in Manchester,” he said. Maxie was on edge, too, half-expecting the hunters to track him long before I did. What neither he nor the police knew was that McLean’s friends, by then known as the Winter Hill Gang, had connections at the Boston Globe. They were monitoring out-of-state subscriptions.

But they never came.

And Maxie never left. He gradually began to relax a little and live free. He kept walking the straight and narrow, redefining himself as an honest man doing honest work, and was rewarded for it in more ways than one. Every day, the garage door would rumble up and he’d squint in the streaming sunlight as the latest wreck rolled in. It would be inspected to see the extent of the damage and disassembled to check for structural integrity, and then began the long process of mechanical and frame repair, reassembly, and refinishing. Maxie became an expert in the restoration process—as a former wreck himself, he’d had a head start.

His good work got him promoted. He ran the shop for 30 years.

In the early 1990s, he gave up drinking, cold turkey. Some of that old self-doubt lingered, so he bought a case of beer and left it in the refrigerator. It went stale and was eventually thrown out, untouched. One Saturday afternoon in 2006, the widow who lived next door stepped outside. Maxie was in the yard. “Where are you going?” he called out.

“To Mass.”

“I’m going with you.”

Her name is Regina. “Reggie,” he calls her. They’ve been together ever since.

On New Year’s Day this year, he wasn’t feeling well and went to urgent care. An X-ray was taken, and the radiologist was startled enough to urge an immediate trip to the hospital. At 86, Maxie faces a terror far worse than those Somerville shooters. Cancer was found in his lungs, stomach, liver, prostate, and bones. He’s on hospice care. There hasn’t been much pain yet, but he knows it’s coming and the morphine is in the fridge.

His past finally caught up to him on the first day of Lent. “Is this Maxie Shackelford who used to live in Charlestown?” I asked when I cold-called him. He seemed happy to talk about things other than his health, enthusiastic even. An hour after our first conversation, he called back and invited me to his house for coffee that Saturday. He said he’d remember things better that way.

He canceled on Friday morning. Those old memories had been locked away for too many years; they came careening at him all at once—flashbacks like a war veteran, which he’d almost forgotten he was. He didn’t sleep all night. “The things I saw, the things that were done and had to be done. All my friends murdered like they were. It does something to you,” he told me. “I’m sorry to disappoint you.”

He didn’t disappoint me. A few days later, he called again, and the conversations continued. He became more reflective about his past, reconciling himself to it. “I never should have gotten involved in all that, but I did,” he said. “You know, Buddy McLean called me when I was staying at my mother’s house in Wilmington. I don’t know how he knew I was there or how he got the number, but he told me that a lot of people were speaking up for me and that I should get out of Massachusetts while I still can. But I didn’t; I was young and had to be Mr. Tough Guy, a big shot. I never screwed anybody, though. I think that’s the only reason I’m still around.”

There are other reasons he’s still around: the FBI agents who kept him under surveillance in plain view and thus deterred any attempts on his life; the police officers who grabbed him at Mass General with New Hampshire warrants and got him safely out of the killing field.

Other reasons defy explanation. Had Connie Hughes not spotted the sedan U-turning in the rearview on that misty night, Maxie would’ve gotten an obituary at 31 instead of a scar on his forearm. “Connie saved my life,” he says today. Another tragedy was averted by a glitch in his gun that might have saved his soul. It happened in 1965, when Punchy McLaughlin decided to go to Driscoll’s Bar to see a longshoreman who’d been giving Stevie Hughes a hard time. “I’ll take Maxie with me and kill him,” he said, and off they went. Maxie had a stocking over his head and was guarding the door. Punchy couldn’t find the target, but Maxie saw him standing at the bar inhaling whiskey. He walked over, pulled out his .45, and pulled the trigger—and the gun jammed. Punchy then shot him in the top of the head. They threw the guns into the Charles River and holed up until they heard some surprising news: the longshoreman survived. His nickname? “Lead Head.”

Maxie regrets it. “The things I did in those days were wrong,” he says. “I don’t know what I was thinking back then, but thank God I turned my life around. Could I have done it all on my own? No. No. So many people helped me.”

On the morning of March 3, a Franciscan friar knocked on his door. It was the pastor of his parish, Blessed Sacrament, who’d come to give him Last Rites. Maxie balked when asked if he’d like to make a confession. “Father John, if you hear my sins you won’t wanna be a priest anymore,” he said. Father John assured him that he’d heard it all and that confession is good for the soul. Maxie spilled the beans. Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. It has been . . . about 70 years . . . since my last confession.

“He said, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’” Maxie told me afterward. “It sure made me feel good.” His daughter came by that morning, too, and hospice gave him a bath. The day before, a woman who worked at a nearby salon stopped by and gave him a free haircut. “I love people,” he said, and smiled. “I love having coffee and talking with people. It’s funny how you change through the years. I’m on a walker now and oxygen. I can’t go upstairs anymore, but I try to live every day I have left like it’s a gift. And I’m starting a new venture—once I start with the pain, I’m going all the way up.”

A hospital bill came in the mail, for a $28 co-pay. “Just throw it out,” someone said. Maxie Shackelford, a former loan shark chasing debts, has learned that the dollar isn’t almighty after all, and heaven is higher than a doughnut-shop window.

“No,” he said. “I owe them.”

Postscript: Maxie died at home on the morning of March 27, 2021. Regina held his hand.