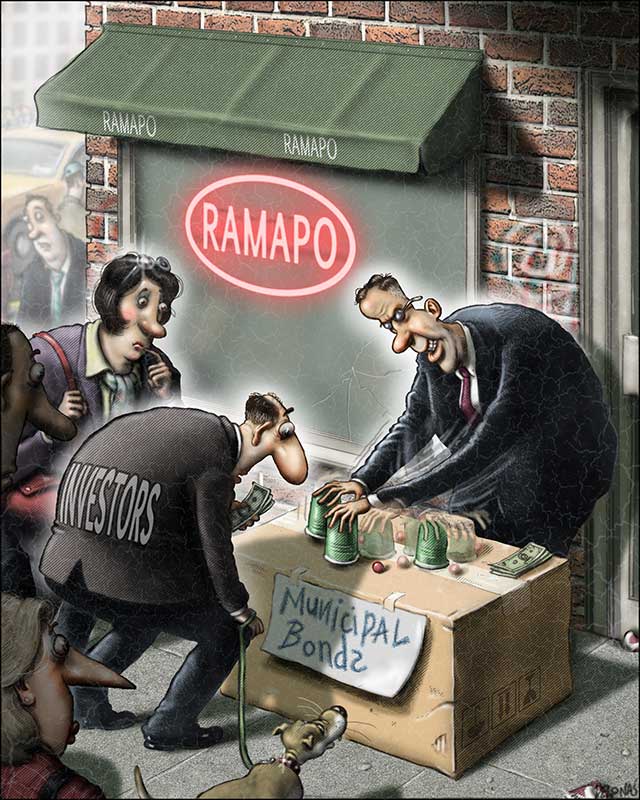

In April, an unprecedented criminal trial will kick off in federal court in New York, with two representatives of the town of Ramapo facing multiple counts of securities fraud. Prosecutors have frequently indicted public officials for embezzling taxpayer money or taking bribes, but this case marks the first attempt to convict officials for fabricating a town’s financial statement in order to raise money in the bond market—in this instance, to pay for a new minor-league baseball stadium. Ramapo town supervisor Christopher St. Lawrence and Ramapo Local Development Corporation executive director N. Aaron Troodler “kicked truth and transparency to the curb,” alleges the indictment, by lying to investors about the town’s crumbling finances. Among the maneuvers the pair employed, prosecutors say, was to shift around assets in city accounts and to exaggerate the size of payments the town had received from the Federal Emergency Management Agency for cleanup after Superstorm Sandy.

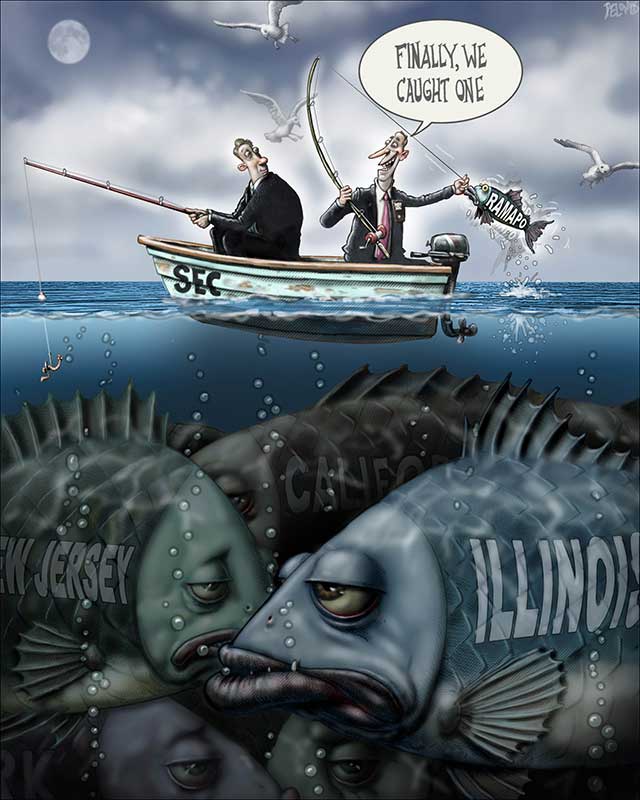

The trial will receive scrutiny in government circles for good reason: tens of thousands of local government entities issue bonds, and some employ dubious accounting techniques “that obscure their true financial position,” according to a 2015 report of the Volcker Alliance, a good-government group led by former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker. For decades, officials rarely paid a price for using such suspect fiscal moves, and some have even grown bold in the practice. A California official recently lightheartedly described some budget proposals to his colleagues as “a little Enron accounting.” But since the middle of the last decade, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of Justice have started to crack down on misleading financial reporting by local governments. A trend that has endured through consecutive Republican and Democratic administrations, the crackdown is likely to continue under a President Donald Trump because Republican SEC appointees have generally supported tougher standards. The potentially groundbreaking outcome of the Ramapo trial—with officials facing jail time—could shake up not only municipal finance but also government accounting standards across America.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Consecutive acts of Congress, passed in 1933 and 1934, fashioned securities law in the United States and created the Securities and Exchange Commission to enforce those laws. To bring sunlight to the markets, the SEC required firms that issued securities to register with the commission and to produce periodic financial reports. Congress exempted municipalities that issued securities from the disclosure rules, however. At the time, large institutions were the principal buyers of government bonds. Lawmakers believed that these organizations could protect themselves from fraud—and defaults were rare in the field, anyway. But the SEC did warn state and local officials that antifraud statutes made it illegal to mislead investors by making untrue statements in, or omitting significant facts from, financial reports.

By the 1970s, the municipal bond market had grown large and complex enough to lead many to believe that the SEC should have a stronger hand in regulating how cities and states reported financial data. Abuses in the marketplace had become more common, including misrepresentations from governments about the nature of some muni bonds and how the revenues they generated would get used. Lobbying by municipal officials derailed most reform efforts, but a compromise in the 1975 Securities Act Amendments gave the SEC the power to regulate the brokers and dealers who underwrote and sold muni bonds. Then, in 1983, the Washington Public Power Supply System reneged on payments on $2.5 billion in bonds that it had floated to build nuclear power plants. After a six-year odyssey, investors got back as little as ten cents on the dollar for those securities. In response, the SEC developed rules—sometimes referred to as “backdoor regulation”—that required the dealers underwriting municipal securities to obtain agreements from local governments to issue fiscal information when they sold bonds. In 1994, after Orange County defaulted on its debt—its treasurer had lost some $1.5 billion on speculative investments—the SEC expanded its backdoor regulation, requiring underwriters to ensure that governments with bonds in circulation issue annual updates on their financial condition.

But many governments have skirted these requirements. A DCP Data study of municipal-disclosure practices over a ten-year period after the Orange County bankruptcy found that 50 percent of governments with bonds outstanding failed at least once to issue financial statements that they’d pledged to make, and a quarter skipped disclosures for three or more years. In a follow-up study, DCP Data found numerous cases in which investors purchased the securities of governments that subsequently developed financial difficulties but that had filed no disclosure statements for at least the two previous years. Investors had no way to “protect themselves with independent research,” the study concluded.

“Its pension system was at least as underfunded as Jersey’s, yet Illinois had been portraying its fiscal situation rosily.”

In a 2007 speech, former SEC chairman Christopher Cox warned about the inadequacy of investor protections in the increasingly complex municipal bond market. For decades, he noted, the SEC could intervene in cases only after evidence of fraud emerged. Cox likened the situation to “assuring a skydiver who’s now in the hospital in traction that, rest assured, next time that parachute is going to open.” Along with the extra risk for investors, Cox added, taxpayers paid the price in the form of “higher bills when municipal finance isn’t conducted properly.” Among the shortcomings of current regulation, Cox pointed to the voluntary fiscal standards that the Government Accounting Standards Board had come up with for municipalities, generally less rigorous in crucial areas like pension-fund accounting than the mandatory standards that private firms issuing securities must follow. “The lack of uniformly applied, generally accepted accounting standards” for governments, Cox said, threatened to undermine “the integrity of the municipal market.”

In the aftermath of such reports, and of rising defaults beginning in late 2007, the SEC began scrutinizing what governments said in their financial statements. The commission first signaled its intentions in April 2008, when it charged five San Diego officials, including the former city manager and auditor, with fraud in connection with a pension scandal that brought the city to the edge of bankruptcy. Investigators accused the officials of certifying financial statements in 2002 and 2003 that they knew were false; they had failed to disclose that the city was purposely underfunding its pension system and was facing a fiscal squeeze. The accused eventually agreed to pay penalties ranging from $5,000 to $25,000—the first such fines levied against officials in a muni-fraud case.

The commission broke new ground in 2010 by establishing a unit to investigate misconduct in municipal finance, with an emphasis on pension funding. In August of that year, for the first time, it charged a state with fraud, contending that New Jersey had issued documents during bond offerings between 2001 and 2007 that gave the impression that its government-employee pension system was well funded; in reality, the state couldn’t afford to make adequate contributions to the system. New Jersey didn’t disclose the cost of enhanced benefits that it had awarded employees in 2001, and it continued to tout a plan to fix the system, though the plan had already been abandoned. “New Jersey didn’t give its municipal investors a fair shake,” the SEC complained. Even so, the SEC decided against fining the state. As former SEC chairman Cox observed, the “penalty would be paid in tax dollars from the pockets of law-abiding citizens.”

If New Jersey was guilty of fraud for such a lack of disclosure, some observers argued, so were most states. Illinois is a striking example, as I pointed out in 2010 in the Wall Street Journal. Its pension system was at least as underfunded as Jersey’s, yet the state had been painting its fiscal situation rosily in investor presentations and overhyping a reform measure as a solution to its fiscal problems. As it turned out, the SEC was already on to Illinois. In March 2013, the commission charged the state with fraud—again, largely due to misrepresentations about pensions, including failing to tell investors that it was using a controversial actuarial method that backloaded payments on pension obligations into the future, relieving the current government of some obligations but increasing risks that the fund could become insolvent. The SEC again chose not to fine the state, and it singled out no one in government as responsible for the mess. Instead, the commission blamed poor staff training and accepted Illinois’ pledge to rectify the situation.

Regulators took another step toward tougher enforcement in a 2013 case involving Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The case revolved around $260 million in debt that the city floated to upgrade a resource-recovery center with new technologies, which ultimately failed to work. Unusually, because the city stopped issuing financial reports as it hurtled toward a bond default, the SEC decided “to review other public statements from the city about its fiscal situation.” In particular, investigators focused on a 2009 state-of-the-city report by Harrisburg mayor Stephen Reed that underplayed problems with the recycling project and presented too bright a picture of the city budget. State-of-the-city and state-of-the state addresses by mayors and governors are often political speeches that portray an administration favorably, of course, so the SEC’s move was striking. The warning was clear: keep reneging on your agreements to file accurate disclosure statements, and regulators will focus on less formal statements to judge whether a government is misleading investors.

The Harrisburg case was also notable because the Justice Department apparently opened a criminal investigation against former mayor Reed. Though the agency won’t comment on its investigations, current mayor Eric Papenfuse—a relentless critic, as a city councilman, of Reed’s financial practices—says that Federal Bureau of Investigation agents interviewed him several times, trying to determine whether to file criminal charges in the case. Nothing came of the FBI inquiry, prompting SEC commissioner Daniel Gallagher to issue a mild rebuke to investigators: “Municipalities don’t commit frauds, people do.” Eventually, Pennsylvania’s attorney general charged Reed with 449 counts of wrongdoing relating to his mayoral tenure and his use of borrowed money. A state judge dismissed many of these, but Reed still faces 144 charges, most accusing him of stealing historical artifacts bought with borrowed city money.

Regulators have also concentrated on debt raised to back government economic-development projects. In November 2013, the SEC accused the Greater Wenatchee Regional Events Center Public Facilities District—a municipal corporation formed by cities and counties in Washington State to run a local entertainment complex—of misrepresentations in its bond documents and slapped it with a $20,000 penalty. This was the first time that the SEC had ever fined a municipal issuer. Among the district’s misdeeds: failing to note in its disclosures that an independent consultant had questioned the viability of the entertainment center’s economic projections. Many governments that finance development projects—from stadiums and arenas to convention centers and museums—raise money from investors by relying on economic studies with starry-eyed predictions of future revenues. If these revenues fall short, the burden falls on bondholders or on taxpayers.

In another example, from 2008 through 2010, Harvey, Illinois, floated several bond offerings to raise money to help investors develop a hotel in town. When the investors ran into trouble advancing the project, Harvey used some of the money instead to fund the city’s payroll and other operating costs; the hotel, the revenues of which were supposed to pay off the bond debt, never opened. “Investors were told one thing and the city did another,” the SEC’s complaint pointed out. For his role in the scheme, Harvey mayor Eric Kellogg agreed last spring to pay a $10,000 fine and never participate again in a bond offering. That followed a $30,000 fine against the city’s comptroller, whom the SEC also banned from the bond business.

“Many governments that finance development projects raise money by relying on starry-eyed economic studies.”

The SEC’s actions against officials are expanding. In March 2016, the commission fined the California Westlands Water District and several of its executives, after charging them with bond fraud. Westlands had agreed in previous bond offerings to maintain revenues equal to 125 percent of the debt service that it pays to bondholders yearly, so as to reassure investors that the district could cover its obligations. During California’s recent drought, recognizing that reductions in water supply would cut its revenues, the agency decided that, instead of raising rates on customers, it would reclassify money it already had on its books as new revenues—the move that general manager Thomas Birmingham described as “a little Enron accounting.” In subsequent bond-disclosure filings, the agency maintained that it was honoring its promises to investors to maintain its debt-service ratio. Westlands subsequently agreed to pay a $125,000 fine, while Birmingham and his assistant, Louie Ciapponi, were hit with $50,000 and $20,000 penalties, respectively.

Regulators have taken a particularly tough stand against municipalities with a pattern of wrongdoing. Last September, SEC lawyers won an unprecedented jury trial seeking fines and penalties against Miami and its former budget director over allegations that they misled investors in 2009 bond offerings. At the heart of the case are various dubious financial moves, principally revolving around the city’s shifting of money from its capital account—meant to fund building projects—to its general fund, trying to mask budget deficits caused by rising health-care and pension costs and shrinking tax collections. Miami maintained that the transferred funds were surplus dollars; they were, in fact, funds for yet-to-be-completed projects. The SEC also charged the city with failing to abide by the commission’s 2003 cease-and-desist order over similar budget maneuvers. When the city and its former budget director, Michael Boudreaux, resisted penalties that the SEC wanted to impose, the commission sued in federal court; a jury found both the city and Boudreaux guilty. Afterward, the SEC warned that this wouldn’t be the last such fraud trial: “We will continue to hold municipalities and their officers accountable, including through trials, if they engage in financial fraud or other conduct that violates the federal securities laws.”

In Ramapo, federal prosecutors have turned a municipal securities case into a criminal conspiracy indictment. The U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Manhattan, Preet Bharara, alleges that Ramapo supervisor St. Lawrence and Troodler, who ran the town’s local development not-for-profit, colluded to hide the town’s involvement in a $58 million minor-league stadium project, after voters had overwhelmingly rejected a resolution to back bonds to help build the facility. Though St. Lawrence subsequently declared that private funds would be used to build the stadium, he and Troodler took steps to inflate the town’s balance sheet and conceal its financing of the stadium, the indictment alleges. That included keeping on Ramapo’s books $3.67 million from the sale of town land that never went through. The indictment also alleges that St. Lawrence hid fiscal problems by transferring assets from a dedicated town account, the Ambulance Fund—which received money from taxes imposed on properties within a special district in Ramapo—to the town’s general fund, which gets its revenues from taxes on all property. The mixing of separate accounts with different tax bases violates state law, the indictment maintains.

Even after the FBI raided Ramapo’s offices in May 2013, prosecutors contend, St. Lawrence sought to hide problems from investors and taxpayers by claiming $3.1 million in federal disaster aid from Superstorm Sandy—though Ramapo had yet to submit claims to the feds for storm damage. The scheme, investigators argue, obscured a yawning budget deficit as the town went to the market to sell bonds. The defendants have pled not guilty, claiming that they relied on the advice of lawyers, accountants, and auditors for the various moves made.

Regulators make powerful accusations in these cases, invoking words and phrases like “fraud,” “conspiracy,” and “misrepresentations.” Yet much of what the SEC has criticized municipalities for doesn’t seem uncommon by the typical accounting standards of today’s cities and states. Elected officials acknowledge as much. In a 2010 report, “The Deficit Shuffle,” New York State comptroller Thomas DiNapoli accused his own state government of “fiscal manipulations” that gave a “distorted view of the State’s finances.” He called certain state budget practices “a fiscal shell game,” intended to mask “the true magnitude of the State’s structural budget deficit.”

And DiNapoli wasn’t alone. A 2015 Volcker Alliance report observed that “many states continue to balance their budgets using accounting and other practices that obscure rather than clarify spending choices.” Similarly, the Institute for Truth in Accounting has identified a host of gimmicks that state and local governments employ to hide deficits and pretend to balance budgets. In a 2015 report, the group pointed out that 40 states failed to balance their budgets in their most recent financial year, even though their official documents said otherwise.

“It may be time to form an independent body to set proper accounting standards for governments with public debt.”

If questionable budgeting practices are as common as these and similar reports suggest, regulators have a massive task ahead—and buyers should beware. According to a 2012 SEC report, America is home to some 44,000 issuers of municipal bonds, compared with fewer than 9,000 corporate issuers. Regulators know that they can’t police all those entities effectively. In fact, several of the SEC’s biggest recent actions originated only after local papers ran investigative pieces on the suspect budgeting, including a July 2009 Miami Herald exposé about that city’s budget mire. Still, regulators hope that their ever-tougher sanctions will make officials less willing to employ spurious budgeting. The SEC created the Municipalities Continuing Disclosure Cooperation Initiative in 2014 to encourage governments voluntarily to report past violations in exchange for lenient terms. The SEC charged 71 municipalities last August with breaches of securities law after they reported themselves and agreed to adopt policies to prevent further abuses. The commission issued no fines in these self-reported cases. Regulators have also extended the program to private firms that underwrite municipal securities, offering moderate penalties to those that self-report that they’ve sold municipal bonds with offering statements that contain missing or inaccurate information. Last June, the agency charged 36 firms under the program. Since then, the SEC has said that it will no longer offer settlements to municipalities or firms.

The larger question, as an SEC under President Trump debuts, is whether investors and, by extension, taxpayers should demand more reforms and greater supervision of local government accounting. Local officials have long argued that Washington has no right to dictate fiscal policy to them under a federalist system of government, but that doesn’t give states and local officials a license to mislead securities buyers. Among potential reforms that might offer better protection would be giving the SEC the right to designate what information municipal governments should include in financial reports, and how they should present it. It may also be time to designate an independent body to set proper accounting standards for governments with public debt—something that the Financial Accounting Standards Board does for private firms that issue securities. The current body, the Government Accounting Standards Board, recommends policies that governments can voluntarily follow, but GASB has faced criticism over the years for aligning too closely with the interests of local governments. Private groups like the National Federation of Municipal Analysts have also suggested requiring municipal bond issuers to report financial information more promptly, giving the SEC the right to enforce deadlines, and ensuring that documents that accompany new offerings clearly state the source of funds that would be used to repay investors.

For decades, corporations that failed to adhere to the SEC’s stringent financial standards have been excoriated in the press, and their executives have been pressured to resign by elected officials. Now the SEC is acknowledging “potentially widespread violations of the federal securities laws by municipal issuers and underwriters.” At the heart of the problem are increasingly troubling state and local accounting practices that victimize not only investors but taxpayers. A shakeup is overdue.