Articles about America’s high levels of child poverty are a media evergreen. Here’s a typical entry, courtesy of the New York Times’s Eduardo Porter: “The percentage of children who are poor is more than three times as high in the United States as it is in Norway or the Netherlands. America has a larger proportion of poor children than Russia.” That’s right: Russia.

Outrageous as they seem, the assertions are true—at least in the sense that they line up with official statistics from government agencies and reputable nongovernmental organizations like the OECD and UNICEF. International comparisons of the sort that Porter makes, though, should be accompanied by a forest of asterisks. Data limitations, varying definitions of poverty, and other wonky problems are rampant in these discussions.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The lousy child-poverty numbers should come with another qualifying asterisk, pointing to a very American reality. Before Europe’s recent migration crisis, the United States was the only developed country consistently to import millions of very poor, low-skilled families, from some of the most destitute places on earth—especially from undeveloped areas of Latin America—into its communities, schools, and hospitals. Let’s just say that Russia doesn’t care to do this—and, until recently, Norway and the Netherlands didn’t, either. Both policymakers and pundits prefer silence on the relationship between America’s immigration system and poverty, and it’s easy to see why. The subject pushes us headlong into the sort of wrenching trade-offs that politicians and advocates prefer to avoid. Here’s the problem in a nutshell: you can allow mass low-skilled immigration, which many on the left and the right—and probably most poverty mavens—consider humane and quintessentially American. But if you do, pursuing the equally humane goal of substantially reducing child poverty becomes a lot harder.

In 1964, the federal government settled on a standard definition of poverty: an income less than three times the value of a hypothetical basic food basket. (That approach has its flaws, but it’s the measure used in the United States, so we’ll stick with it.) Back then, close to 23 percent of American kids were poor. With the important exception of the years between 1999 and 2007—following the introduction of welfare reform in 1996—when it declined to 16 percent, child poverty has bounced within three points of 20 percent since 1980. Currently, about 18 percent of kids are below the poverty line, amounting to 13,250,000 children. Other Anglo countries have lower child-poverty rates: the OECD puts Canada’s at 15 percent, with the United Kingdom and Australia lower still, between 11 percent and 13 percent. The lowest levels of all—under 10 percent—are found in the Nordic countries: Denmark, Norway, Iceland, and Finland.

How does immigration affect those post-1964 American child-poverty figures? Until 1980, it didn’t. The 1924 Immigration Act sharply reduced the number of immigrants from poorer Eastern European and southern countries, and it altogether banned Asians. (Mexicans, who had come to the U.S. as temporary agricultural workers and generally returned to their home country, weren’t imagined as potential citizens and thus were not subject to restrictive quotas.) The relatively small number of immigrants settling in the U.S. tended to be from affluent nations and had commensurate skills. According to the Migration Policy Institute, in 1970, immigrant children were less likely to be poor than were the children of native-born Americans.

By 1980, chiefly because of the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act, the situation had reversed: immigrant kids were now poorer than native-born ones. That 1965 law, overturning the 1924 restrictions, made “family preference” a cornerstone of immigration policy—and, as it turned out, that meant a growing number of new Americans hailing from less-developed countries and lacking skills. The income gap between immigrant and native children widened. As of 1990, immigrant kids had poverty rates 50 percent higher than their native counterparts. At the turn of the millennium, more than one-fifth of immigrant children, compared with just 9 percent of non-Hispanic white kids, were classified as poor. Today, according to Center for Immigration Studies estimates, 31.1 percent of the poor under 18 are either immigrants or the American-born kids of immigrant parents.

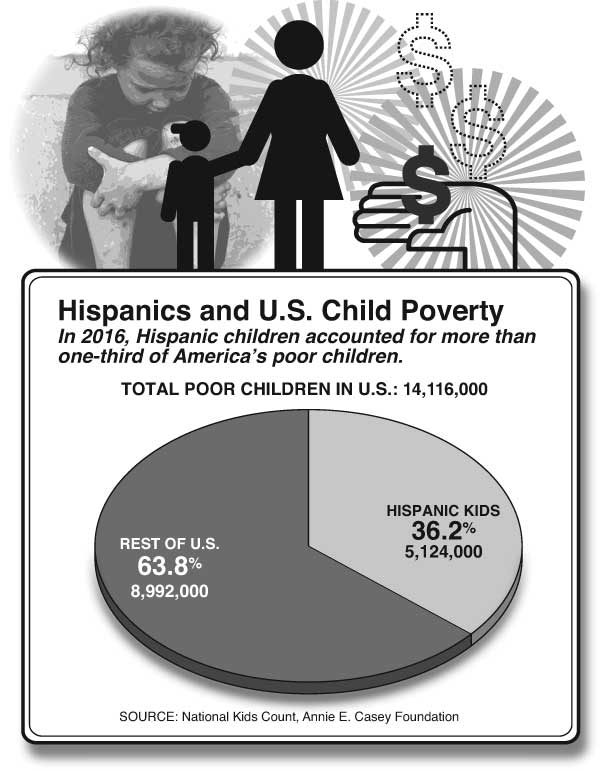

Perhaps the most uncomfortable truth about these figures, and surely one reason they don’t often show up in media accounts, is that a large majority of America’s poor immigrant children—and, at this point, a large fraction of all its poor children—are Hispanic (see chart below). The U.S. started collecting separate poverty data on Hispanics in 1972. That year, 22.8 percent of those originally from Spanish-language countries of Latin America were poor. The percentage hasn’t risen that dramatically since then; it’s now at 25.6 percent. But because the Hispanic population in America quintupled during those years, these immigrants substantially expanded the nation’s poverty rolls. Hispanics are now the largest U.S. immigrant group by far—and the lowest-skilled. Pew estimates that Hispanics accounted for more than half the 22-million-person rise in the official poverty numbers between 1972 and 2012. Robert Samuelson of the Washington Post found that, between 1990 and 2016, Hispanics drove nearly three-quarters of the increase in the nation’s poverty population from 33.6 million to 40.6 million.

Ironically, then, at the same time that America’s War on Poverty was putting a spotlight on poor children, the new immigration system was steadily making the problem worse. In 1980, only 9 percent of American children were Hispanic. By 2009, that number had climbed to 22 percent. Almost two-thirds of these children were first- or second-generation immigrants, most of whose parents were needy. Nowadays, 31 percent of the country’s Hispanic children are in poverty. That percentage remains somewhat lower than the 36 percent of black children who are poor, true; but because the raw number of poor Hispanic kids—5.1 million—is so much higher (poor black children number 3.7 million), they make up by far the largest group in the child-poverty statistics. As of 2016, Hispanic children account for more than one-third of America’s poor children. Between 1999 and 2008 alone, the U.S. added 1.8 million children to the poverty rolls; the Center for Immigration Studies reports that immigrants accounted for 45 percent of them.

Let’s be clear: Hispanic immigration isn’t the only reason that the U.S. has such troubling child-poverty rates. Other immigrant groups, such as North Africans and Laotians, add to the ranks of the under-18 poor. And American Indians have the highest rates of child poverty of all ethnic and racial groups. These are relatively small populations, however; combine Indians and Laotians, and you get fewer than a half-million poor children—a small chunk of the 14-plus million total.

Even if we were following the immigration quotas set in 1924, the U.S. would be something of a child-poverty outlier. The nation’s biggest embarrassment is the alarming percentage of black children living in impoverished homes. Unsurprisingly, before the civil rights movement, the numbers were higher; in 1966, almost 42 percent of black kids were poor. But those percentages started to improve in the later 1960s and in the 1970s. Then they soared again. By the 1980s and early 1990s, black child poverty was hovering miserably between 42 percent and almost 47 percent. Researchers attribute the lack of progress to the explosion in single-parent black families and welfare use. The current percentage of black kids living with a single mother—66 percent—far surpasses that of any other demographic group. The 1996 welfare-reform bill and a strong economy helped bring black child poverty below 40 percent, a public-policy success—but the numbers remain far too high.

“Policymakers and pundits prefer silence on the relationship between America’s immigration system and poverty.”

Immigrant poverty, though usually lumped within a single “child-poverty” number, belongs in a different category from black or Native American poverty. After all, immigrants voluntarily came to the United States, usually seeking opportunity. And immigrants of the past often found it. The reality of American upward mobility helps explain why, despite real hardships, poor immigrant childhood became such a powerful theme in American life and literature. Think of classic coming-of-age novels like Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (about Irish immigrants), Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep (Jewish immigrants), and Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones (West Indians), all set in the first decades of the twentieth century. With low pay, miserable work conditions, and unreliable hours, the immigrant groups that such novels depicted so realistically were as poor as—and arguably more openly discriminated against than—today’s Mexicans or Bangladeshis.

Their children, though, didn’t need a ton of education to leave the hard-knocks life behind. While schools of that era were doubtless more committed to assimilating young newcomers than are today’s diversity-celebrating institutions, sky-high dropout rates limited their impact. At the turn of the twentieth century, only 5 percent of the total population graduated from high school; the rate among immigrants would have been even lower. That doesn’t mean that education brought no advantages. Though economist George Borjas notes that endemic truancy and interrupted studies had ripple effects on incomes into following generations, the pre–World War II industrial economy offered a “range of blue collar opportunities” for immigrant children, as sociologists Roger Waldinger and Joel Perlman observe, and it required “only modest educations to move a notch or two above their parents.” It may have taken more than one generation, but most immigrant families could expect, if not Horatio Alger–style ascents, at least middle-class stability over time.

America’s economy has transformed in ways that have blocked many of the avenues to upward mobility available to the immigrant families of the past. The kind of middle-skilled jobs that once fed the aspirations of low-income strivers are withering. “Modest educations” will no longer raise poor immigrant children above their parents’ station. Drop out of high school, and you’ll be lucky to be making sandwiches at a local deli or cleaning rooms at a Motel 6. Even a high school diploma can be a dead end, unless supplemented by the right kind of technical training. Get a college degree, however, and it is a different, happier, story.

Yes, some immigrant groups known for their obsessional devotion to their children’s educational attainment (Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants come to mind) still have a good shot at middle-class stability, even though the parents typically arrive in America with little skill or education and, working in low-wage occupations, add to poverty numbers in the short term. But researchers have followed several generations of Hispanics—again, by far the largest immigrant group—and what they’ve found is much less encouraging. Hispanic immigrants start off okay. Raised in the U.S., the second generation graduates high school and goes to college at higher rates than its parents, and it also earns more, though it continues to lag significantly behind native-born and other immigrant groups in these outcomes. Unfortunately, the third generation either stalls, or worse, takes what the Urban Institute calls a “U-turn.” Between the second and third generation, Hispanic high school dropout rates go up and college-going declines. The third generation is more often disconnected—that is, neither attending school nor employed. Its income declines; its health, including obesity levels, looks worse. Most disturbing, as we look to the future, a third-generation Hispanic is more likely to be born to a single mother than were his first- or second-generation predecessors. The children of single mothers not only have high poverty rates, regardless of ethnic or racial background; they’re also less likely to experience upward mobility, as a mountain of data shows.

The Hispanic “U-turn” probably has many causes. Like most parents these days, Hispanics say that they believe that education is essential for their children’s success. Cultural norms that prize family and tradition over achievement and independence often stand in the way. According to a study in the Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, Hispanic parents don’t talk and read to their young children as much as typical middle-class parents, who tend to applaud their children’s attempts at self-expression, do; differences in verbal ability show up as early as age two. Hispanic parents of low-achieving students, most of whom also voiced high academic hopes for their kids, were still “happy with their children’s test scores even when the children performed poorly.” Their children tended to be similarly satisfied. Unlike many other aspiring parents, Hispanics are more reluctant to see their children travel to magnet schools and to college. They also become parents at younger ages. Though Hispanic teen birthrates have fallen—as they have for all groups, apart from American Indians—they remain the highest in the nation.

The sheer size of the Hispanic population hinders the assimilation that might moderate some of these preferences. Immigrants have always moved into ethnic enclaves in the United States when they could, but schools and workplaces and street life inevitably meant mixing with other kinds, even when they couldn’t speak the same language. In many parts of the country, though, Hispanics are easily able to stick to their own. In fact, Generations of Exclusion, a longitudinal study of several generations of Mexican-Americans, found that a majority of fourth-generation Mexican-Americans live in Hispanic neighborhoods and marry other Hispanics.

Other affluent countries have lots of immigrants struggling to make it in a postindustrial economy. Those countries have lower child-poverty rates than we do—some much lower. But the background of the immigrants they accept is very different. Canada, New Zealand, and Australia are probably the best points of comparison. Like the United States, they are part of the Anglosphere and historically multicultural, with large numbers of foreign-born residents. However, unlike the U.S., they all use a points system that considers education levels and English ability, among other skills, to determine who gets immigration visas. The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project calculates that, while 30 percent of American immigrants have a low level of education—meaning less than a high school diploma—and 35 percent have a college degree or higher, only 22 percent of Canadian immigrants lack a high school diploma, while more than 46 percent have gone to college. (Canada tightened its points system after a government study found that a rise in poverty and inequality during the 1980s and 1990s could be almost entirely attributed to an influx of poorer immigrants.) Australia and New Zealand also have a considerably more favorable ratio of college-educated immigrants than does the United States. The same goes for the U.K.

The immigration ecosystem of the famously egalitarian Nordic countries also differs from the U.S.’s in ways that have kept their poverty numbers low. Historically, the Nordics didn’t welcome large numbers of greenhorns. As of 1940, for instance, only 1 percent of Sweden’s population was foreign-born, compared with almost 8.8 percent of Americans. After World War II, Nordic immigration numbers began rising, with most of the newcomers arriving from developed countries, as was the case in the U.S. until 1965. In Finland and Iceland, for instance, the plurality of immigrants today is Swedish and Polish, respectively. In Norway, the majority of immigrants come from Poland and Lithuania. Note that these groups have low poverty rates in the U.S., too.

Sweden presents the most interesting case, since it has been the most welcoming of the Nordic countries—and it has one of the most generous welfare states, providing numerous benefits for its immigrants. For a long time, the large majority of Sweden’s immigrants were from Finland, a country with a similar culture and economy. By the 1990s, the immigrant population began to change, though, as refugees arrived from the former Yugoslavia, Iran, and Iraq—populations with little in common culturally with Sweden and far more likely to be unskilled than immigrants from the European Union. By 2011, Sweden, like other European countries, was seeing an explosion in the number of asylum applicants from Syria, Afghanistan, and Africa; in 2015 and 2016, there was another spike. Sweden’s percentage of foreign-born has swelled to 17 percent—higher than the approximately 13 percent in the United States.

How has Sweden handled its growing diversity? We don’t have much reliable data from the most recent surge, but numbers from earlier this decade suggest the limits of relying on copious state benefits to acclimate cultural outsiders. In the U.S., immigrants are still more likely to be employed than are the native-born. In Sweden, the opposite holds. More than 26 percent of Swedish newcomers have remained unemployed long-term (for more than a year). Immigrants tend to be poorer than natives and more likely to fall back into poverty if they do surmount it. In fact, Sweden has one of the highest poverty rates among immigrants relative to native-born in the European Union. Most strikingly, a majority of children living in Sweden classified as poor in 2010 were immigrants.

Despite its resolute antipoverty efforts, Sweden has, if anything, been less successful than the U.S. at bringing its second-generation immigrants up to speed. According to the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey, Sweden has “declined over the past decade [between 2005 and 2015] from around average to significantly below average . . . . No other country taking part in PISA has seen a steeper fall.” The Swedish Education Agency reports that immigrant kids were responsible for 85 percent of a decline in school performance.

Outcomes like these suggest that immigration optimists have underestimated the difficulty of integrating the less-educated from undeveloped countries, and their children, into advanced economies. A more honest accounting raises tough questions. Should the United States, as the Trump administration is proposing, and as is already the case in Canada and Australia, pursue a policy favoring higher-skilled immigration? Or do we accept higher levels of child poverty and lower social mobility as a cost of giving refuge and opportunity to people with none? If we accept such costs, does it even make sense to compare our child-poverty numbers with those of countries like Denmark or Sweden, which have only recently begun to take in large numbers of low-skilled immigrants?

Recent events in Denmark and Sweden put another question in stark relief. How many newcomers—especially from very different cultures—can a country successfully absorb, and on what timetable? A surge of asylum seekers beginning in 2015 forced both countries to introduce controls at their borders and limits to asylum acceptances. Their existing social services proved unable to cope with the swelling ranks of the needy; there was not enough housing, and, well, citizens weren’t always as welcoming as political leaders might have wished. The growing power of anti-immigrant political parties has shocked these legendarily tolerant cultures.

And yet one more question: How long can generous welfare policies survive large-scale low-skilled immigration? The beneficent Nordic countries are not the only ones that need to wonder. The National Academies of Sciences finds that immigration to America has an overall positive impact on the fiscal health of the federal government, but not so for the states and localities that must pay for education, libraries, some social services, and a good chunk of Medicaid. Fifty-five percent of California’s immigrant families use some kind of means-tested benefits; for natives, it’s 30 percent. The centrist Hamilton Project observes that high-immigrant states—California, New York, New Jersey, among others—“may be burdened with costs that will only be recouped over a number of years, or, if children move elsewhere within the United States, may never fully be recovered.”

In short, confronting honestly the question of child-poverty rates in the United States—and, increasingly, such rates in other advanced countries—means acknowledging the reality that a newcomer’s background plays a vital role in immigrant success. Alternatively, of course, one can always fall back on damning worries about our current immigration system as evidence of racism. Remember November 8, 2016, if you want to know how that will play out.

A young girl eats at a Salvation Army Thanksgiving dinner in Santa Ana, California. (ALLEN J. SCHABEN/LOS ANGELES TIMES/GETTY IMAGES)