It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

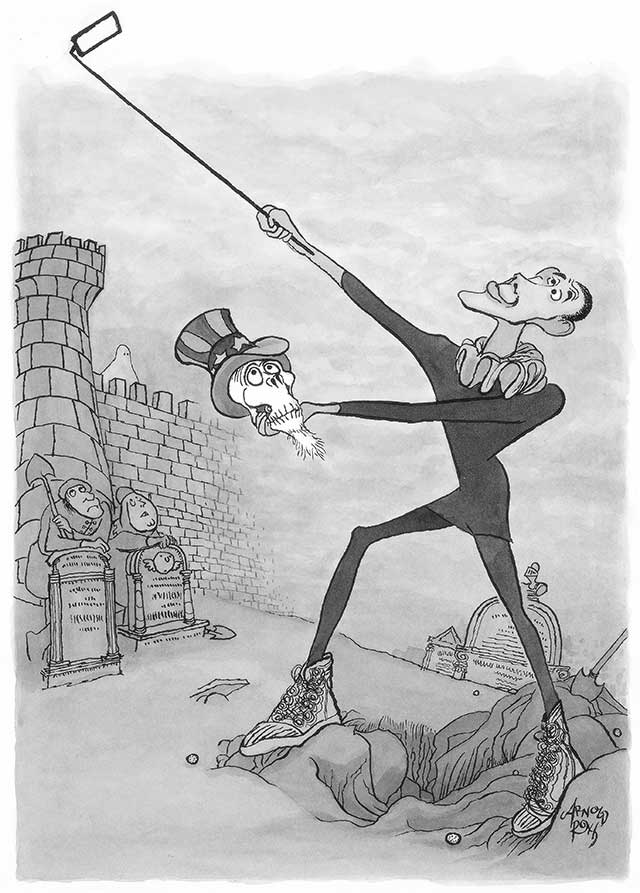

In the summer of 2008, Barack Obama was hailed as the healer who would redeem a barren time. (See “Obama, Shaman,” Summer 2008.) He “isn’t really one of us,” journalist Mark Morford opined in the San Francisco Chronicle. “Not in the normal way, anyway. Many spiritually advanced people I know (not coweringly religious, mind you, but deeply spiritual) identify Obama as a Lightworker, that rare kind of attuned being who has the ability to lead us not merely to new foreign policies or health care plans or whatnot, but who can actually help usher in a new way of being on the planet.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Yet when, in January, the 44th president made his way through the Capitol to witness the inauguration of his successor, even those on his side could not disguise a sense of letdown. In The New Yorker, George Packer lamented Obama’s “difficulty in sustaining public support for his program and his party.” Slate’s Jacob Weisberg conceded that Obama’s “inability to produce any durable consensus must count as a tremendous disappointment.” Harvard’s Stephen Walt went so far as to say that Obama’s presidency, for all its promise, was a “tragedy.”

The rest of the country was no less ambivalent. Polls showed Obama to be personally popular as he left office; but at the same time, the Associated Press reported, more Americans felt that his eight years in power had “divided the country” than felt that they had “brought people together.” The result, as Obama departed the White House, was that “just 27 percent see the U.S. as more united as a result of his presidency.”

What went wrong? The word we reach for, in attempting to explain an ascent like Obama’s, is “charisma.” But it is a treacherous word, with several meanings. Max Weber, who first applied the term to secular leadership, thought William Ewart Gladstone its most notable modern exemplar. In his 1879 Midlothian campaign, Gladstone broke with convention to speak directly to the British people at mass meetings and open-air rallies. The spectacle alarmed Queen Victoria, who, after the victory of Gladstone’s Liberals in the 1880 general election, at first refused to accept the Grand Old Man as her prime minister. She would “sooner abdicate,” she wrote, “than send for or have any communication with that half mad firebrand who wd soon ruin everything & be a Dictator.”

Gladstone’s charisma was an instrument of policy: he sought both to end British support for the Ottoman Empire (which Benjamin Disraeli was backing as a counterweight to Russia) and to advance his own liberal agenda. By contrast, Obama’s 2008 campaign is remarkable for how little it had to do with policy. It was not the candidate’s “new foreign policies or health care plans or whatnot” that captivated the imagination of the country and, indeed, the world that year. Obama’s campaign closely resembled the book that served as its blueprint. What at first seems the weakness of The Audacity of Hope—its vacuousness—is, in fact, its genius. In it, Obama conspicuously resists the temptation to put forward specific solutions to the nation’s problems. “I offer no unifying theory of American government,” he conceded in the prologue, “nor do these pages provide a manifesto for action, complete with charts and graphs, timetables and ten-point plans.”

What Obama offered in lieu of a program was an image—one calculated to appeal to the mood of the moment, one that he could rely on his enthusiasts in the media to embellish. (“I was,” he admitted, “the beneficiary of unusually—and at times undeservedly—positive press coverage.”) He was a child of Kenya and Kansas, of Hawaii and Indonesia, and the exoticism of his background seemed to mark him out as the incarnation of the multicultural romance of the age. The media swooned. In extravagant panegyrics, much was made of the coolness of his demeanor, his Harvard degree, his literary skill. “I think he’s more talented than anyone in my lifetime,” the New York Times’s David Brooks said. “I mean, he is pretty dazzling when he walks into a room.”

That so prodigious a combination of virtues should be found in one man—and a black man, too!—enthralled the fourth estate. For as the novelist Darryl Pinckney observed in The New York Review of the Books, 2008 was “not a color-blind election. People aren’t voting for Obama in spite of the fact that he is black, or because he is only half-black, they are voting for him because he is black, and this is a whole new feeling in the country and in presidential politics.” The desire to be part of the “whole new feeling” perhaps accounts for the element of condescension evident in the press hysteria of the time—the cooing over complexion—as well as the parading of righteousness. In romancing Obama’s image, the journalist could exhibit his own purity on race questions and congratulate himself on his virtue.

Like other purveyors of fables, the Obama romanticists pointed to the fabulous qualities of their hero’s ascent. The Washington Post’s David Maraniss, musing in Haji Ramli Street in Jakarta, where Obama had passed part of his boyhood, “could not help but be overwhelmed by how utterly improbable” it was that such a child should have grown up to conquer the plain-vanilla heights of the Yankee political establishment. The twists and turns in Obama’s story were made to seem as magically implausible as those in a tale from The Arabian Nights, and it was a bit disconcerting to find, in media accounts of the golden child of the souk making his way to his miraculous treasure, a reworking of Orientalist fantasies that the late Professor Said taught good liberals to deplore.

Yet Obama’s image owed quite as much to repackaged Western myths of the hero as it did to romanticized visions of the East. The motive of the Old Western hero, Lionel Trilling observed, “is the legendary one of setting out to seek his fortune, which is what the folktale says when it means that the hero is seeking himself.” Obama’s first book, Dreams from My Father, is a quest book, the story of its young hero’s search for a way to reconcile his blackness with his whiteness. The tension between the two identities is resolved when Obama discovers his vocation as a pacifier, a healer of divisions. “Religious or secular, black, white, or brown,” he wrote in The Audacity of Hope, we “need a new kind of politics,” one that could replace the old divisive politics by building “upon those shared understandings that pull us together as Americans.”

Obama was well aware of the appeal of the heroic and redemptive myths that he was tapping. As a student at Columbia, he told a friend that he had been impressed by T. S. Eliot’s poetry, in which he found “a certain kind of conservatism which I respect more than bourgeois liberalism.” He was drawn to what he called the “fatalism” of The Waste Land, born of the poet’s preoccupation with “fertility and death.” Eliot’s fatalism was that of Christianity; not only the title of The Waste Land, Eliot wrote, “but the plan and a good deal of the incidental symbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jesse L. Weston’s book on the Grail legend: From Ritual to Romance.” Eliot equated the Grail that the hero seeks with the fertilizing blood of Christ, which (in theory) could redeem a barren time. Obama found his own Grail not in Christian eschatology but in a redemptive secular politics: he would show his fellow Americans how “we can ground our politics in the notion of a common good.” Divisive public questions could be transcended through the grace latent in the personality of the hero.

It was all very easy for a skeptic to mock, but the image of the redeemer prince, much embellished by Obama’s media devotees, proved immensely appealing in a secular age bored with secularism, a scientific age that found no salvation in science. John Stuart Mill described how, in a moment of disenchantment with the spiritual dullness of liberal progress, he turned for consolation to the poetry of Wordsworth. In 2008, the poetry, the spiritual consolation that a good part of the American electorate sought as an antidote to its own discontents, was Barack Obama himself—or rather, the image that that gifted fabulist impressed upon them.

It wasn’t entirely new. In his 1960 Esquire article on John F. Kennedy, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” Norman Mailer argued that a charismatic leader could liberate America’s hidden potential, all that virtù and desire that had been forced underground both by an unsatisfactory politics and by “mass civilization,” in which so many “electronic circuits” made “men as interchangeable as commodities.” Kennedy, Mailer believed, was the “existential hero” whose “royal image” could be a salve for America’s “malnourished electronic psyches.”

A rambling, self-indulgent piece of writing, Mailer’s essay was more a symptom of the hysteria that Kennedy aroused than a sober analysis of it. What he called his “rich chocolate prose” anticipated the inanities of the more outré expositions of Obama’s own splendors in 2008. Was America brave enough, Mailer asked,

to enlist the romantic dream of itself, would it vote for the image in the mirror of its unconscious, were the people indeed brave enough to hope for an acceleration of Time, for that new life of drama which would come from choosing a son to lead them who was heir apparent to the psychic loins?

This was a roundabout way of saying that it was not Kennedy’s policies that were liberating but his image. It was not his “prefabricated politics” but his charismatic person that would rouse the country from its dogmatic slumbers. That Kennedy was “young, that he was physically handsome, and that his wife was attractive were not,” Mailer maintained, “trifling accidental details but, rather, new major political facts.” A Kennedy presidency, he believed, would “touch depths in American life which were uncharted” and promised to usher in a post-political age in which the nation would “rise above the deadening verbiage of its issues, its politics, its jargon, and live again by an image of itself.”

I suppose that there is a little demon in every soul that would have it grovel before the hero and lick his boots. During most of human history, boot-licking has been the rule rather than the exception, as it continues to be in much of the world today. What is astonishing about Mailer’s apology for the politics of image is how oblivious he is of the morbidity of the thing. The sort of hero-worship that Thomas Carlyle embraced has often been described as a pathology of the Right, but Mailer shows that the Left, too, is hardly immune to its appeal.

The most obvious problem with the politics of image is that its natural home is in authoritarian states, where its purpose is to divert the masses’ attention from whatever policies are being implemented by the hierarchs at the top—thus the personality cults of Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Castro, and others. But in free constitutional states, where politics involves convincing people on the merits, image is largely irrelevant after the election has been won and attention turns to the brass tacks of lawmaking. Kennedy, for all the brilliance of his person, was unable to get his program enacted; Obama, though he saw his health-care legislation pass on a party-line vote, never succeeded in convincing the bulk of the country of its wisdom. The legislation cost him his House majority, and during much of the rest of his presidency, he sought to govern by executive order. It is true that his popular image insulated him, to some extent, from the animosity that, in a free state, government by ukase naturally excites, yet this can scarcely be thought a healthy development in the political life of a republic.

What is most malignant about the politics of image is the way that it induces people to find consolation in remote figures glimpsed in a magazine or projected on a screen. Already, in the nineteenth century, Flaubert showed his Emma Bovary escaping the actual life around her through a fantastic identification with romantic personages and distant scenes. “If only she could lean over the balcony of a Swiss chalet, or enclose her melancholy in a Scottish cottage, with a husband wearing a long black velvet cloak.” As solipsistic technologies offer ever more possibilities of escape—ever more “reality” shows that are fundamentally unreal—life becomes, in the words of Santayana, “the joy of living every life but one’s own.”

Mailer rightly predicted that the politics of image would make for the ultimate reality show. With Kennedy’s election, he wrote, “America’s politics would now be also America’s favorite movie, America’s first soap opera, America’s best-seller.” Resembling Gregory Peck one moment, Marlon Brando the next, Kennedy, in Mailer’s evocation, was less a politician than a “movie star, his coloring vivid, his manner rich, his gestures strong and quick, alive with that concentration of vitality a successful actor always seems to radiate.”

Put to one side how politically corrupting a personality cult of this kind is, how it tempts us to relax our vigilance, to give up the hard work of thinking through the issues on our own because the appealing figure on the screen has done it for us. Put aside, too, the danger inherent in making the chief executive into a quasi-divine figure, the object of adoration more than a little reminiscent of that bestowed on the Roman emperors. What is most troubling about the transformation of yet another realm of experience into an exercise in media-massaged groupthink is that it further diminishes the ever-shrinking zones of life that are lived outside the gravitational pull of mass society and lie beyond the reach of its screen romance.

The deadening of this older way of life—the diminishment of life writ small—began long before the advent of electronic communications. The Viennese thinker Camillo Sitte traced the progress of the bacillus in his 1889 book City Building According to Artistic Principles, in which he described the decay of traditional artistries that gave the old way of living its charm, a charm that can still be sensed in old European towns that have been spared the bulldozers of the barbarians. Here, in ages materially much poorer than our own, was a cultural artistry that was much richer, one that drew on local inspirations to create places where people wanted to be, as opposed to places where they go only for some limited utilitarian purpose, their hearts the whole while being elsewhere, like Emma Bovary’s in her daydreams. From the Piazza San Marco in Venice to the modern shopping mall is a steep descent.

The point is that the genius and passion that once went into the maintenance of local forms are now, to a great extent, channeled into the life of the universal civilization. Instead of being a valued actor on a small stage, one becomes a passive spectator of the drama of the mass stage. The cycle is vicious; as our sense of ourselves as individuals rooted in a particular place among particular people diminishes, we are the more tempted to identify with one or another of the collectivist hordes on offer: the electronic mobs that light up the circuits of Facebook.

Death by monotony, by sameness, by loss of identity,” Gerald Brenan wrote in his classic study, The Spanish Labyrinth, is “the fate held out by the brave new world of universal control and amalgamation.” Our overinvestment of passion in this universal culture not only leads to the drabness and homogenization that Brenan deplored; it also exacerbates the very divisions and animosities that Obama promised to transcend. For just as, in our character as mass-people, we lovingly build up our mass idols and endow them with superhuman, quasi-magical properties, so we as passionately abhor their voodoo-doll nemeses and exaggerate their vices. The apotheosis of Kennedy required the damnation of Nixon. The delirious chants of “yes we can” find their analogue in the no-less-frenzied “lock her up.” The hysterical hatreds of mass politics are inseparable from their equally unreasonable idolatries. It is precisely because the remote personages we adore or revile are essentially unreal, the projections of fantasy, that we respond to them in ways that we rarely respond to those whom we encounter in our ordinary flesh-and-blood lives. The new technology, with all its virtues, has aggravated the evil. Read the comments section of any controversial piece of writing published online, and you find a degree of vitriol and incivility rarely encountered outside the virtual mobocracies of cyberspace.

Ten years after Obama announced his candidacy, his politics of image appears more a symptom of the problems he attempted to address than a solution to them. He promised to bridge our divisions, yet both the hysterical adoration and the fanatical revulsion he inspired had as much to do with a disconnectedness in our manner of living as they did with the ostensible issues of the moment. With the decay of older forms of belonging and of solace, it is perhaps only natural that we should seek synthetic substitutes. But the result is a morbidity that will not be healed with “a fantasy and a trick of fame”—the artifice of image that is becoming the essence of modern politics. Such artifice can only make it worse.