Everybody talks about the weather, as Mark Twain observed—but today, somebody does something about it: the United States government. Since 2005, Washington has spent nearly $300 billion on disaster assistance, and state and local governments have shelled out billions more. This figure doesn’t include the nine-figure toll that the 2017 storm season likely exacted across Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. If trends hold, it’s not unreasonable to predict a half-trillion-dollar storm year within the next decade—an amount that would consume half the nation’s annual Medicare bill.

Much of the spending goes to repairing flooded properties after a hurricane. If the government keeps spending massively on what should be a private-sector concern—rebuilding or repairing individual homes—it won’t be able to afford to invest in what is properly a public-sector concern when it comes to destructive weather events: building or upgrading infrastructure to limit potential storm damage and providing immediate relief after a terrible storm has struck. Taxpayers and people living in harm’s way shouldn’t be the only ones concerned that the current system is unsustainable. Long-term municipal bondholders, too, should be skeptical about additional lending to states and localities at the greatest risk for major storms. Reform is needed.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

A series of natural disasters struck America in 2017, from blizzards to wildfires. But the most disruptive and costly were hurricanes and their attendant floods, responsible for more than two-thirds of disaster spending over the previous decade. A trio of powerful storms—Harvey, Irma, and Maria—made landfall between August and October, causing at least 345 direct deaths and wreaking havoc across southern Texas, southwestern Florida, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Hurricane Harvey and Irma, in Texas and Florida, respectively, inflicted more than $200 billion in damages, private and public. The damage from Maria, which slammed Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, probably totals in the tens of billions of dollars.

The U.S. government’s bill for these storms has yet to be tallied. But Congress already approved $51 billion for Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico in the fall, and as 2017 ended, the House was reportedly preparing an additional $81 billion. This money goes to the three pillars of modern post-storm aid: immediate relief in the form of food, shelter, and medicine to displaced or otherwise disrupted individuals; help for state and local government to repair and replace public infrastructure; and financial aid for people to rebuild their homes.

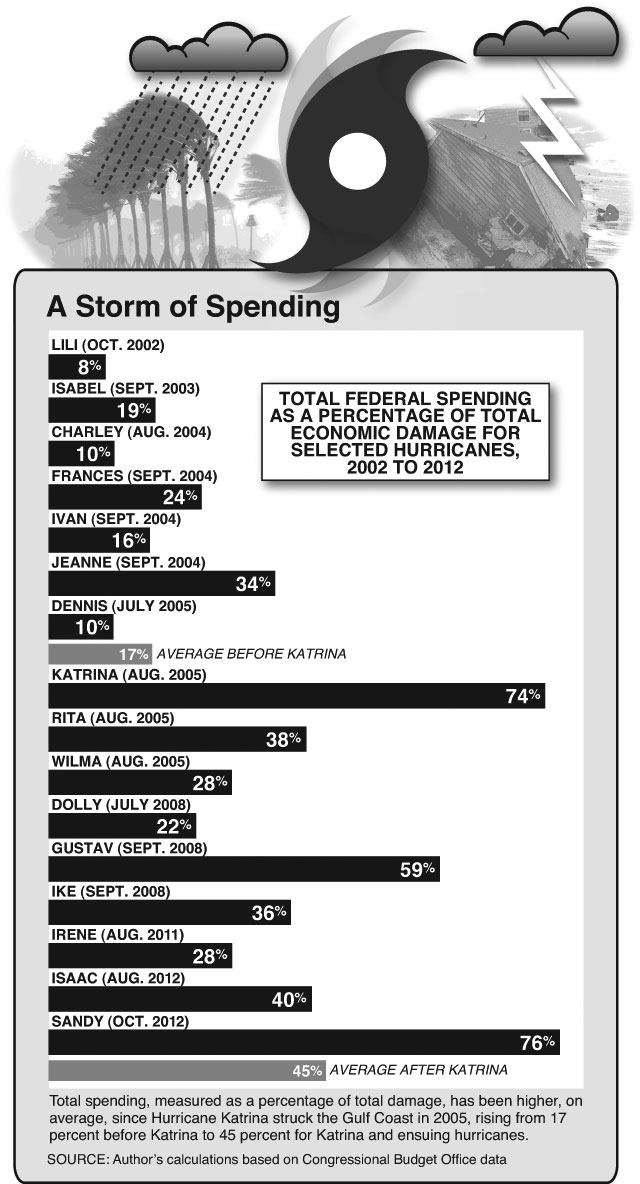

Since Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and Mississippi in 2005, and Superstorm Sandy hit New York and New Jersey in 2012, big numbers for disaster relief no longer surprise. Katrina consumed $108 billion in federal spending; Sandy, $51 billion. Historically, such mass-scale payouts are an aberration. For the seven major storms before Katrina, dating back to 2002, the federal government paid out, on average, 17 percent of the total economic cost of a major hurricane. After Katrina, the figure rose to 45 percent for the subsequent nine storms to 2015, according to the Congressional Budget Office. (The remainder of the loss is borne by private insurers and individual businesses and families.)

Going back further, the federal government spent even less. Florida’s Hurricane Andrew, in 1992, was then the biggest storm ever to hit the United States. Yet Washington allocated just $10.3 billion, in today’s dollars, to help the Sunshine State recover. That effort represented the first time that disaster relief surpassed the $10 billion mark since the government started counting. After Andrew, disaster relief surpassed $10 billion for seven out of the 13 years to 2015, the last year for which full data are available. And in 12 of the 20 years leading up to 2015, notes the Congressional Research Service (CRS), the government required emergency “supplemental” budget measures for disaster relief—suggesting that such measures are becoming regular events.

Several factors have helped transform multibillion-dollar “emergencies” into regular occurrences. First, there is the weather itself. It’s not that we’re seeing more storms because of climate change—at least, not yet. After a review of hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean over more than a century, the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration says that “it is premature to conclude that human activities . . . have already had a detectable impact on Atlantic hurricane . . . activity” (italics theirs). But another factor is making such storms more intense: a well-documented rise in sea levels of more than a foot over the past century, which means more flooding, notes NOAA scientist Martin Hoerling. “High water levels . . . led to [Superstorm] Sandy’s primary impacts on coastal New York and New Jersey,” he notes.

“Hurricane Harvey and Irma, in Texas and Florida, respectively, inflicted more than $200 billion in damages.”

The second factor is population. Between 2000 and 2010, America’s coastal populations grew by 22 percent, faster than the country as a whole, says the CBO. This figure actually lags the growth rate of the decades after 1950, when affordable air conditioning, cheap housing, and lower taxes began luring northerners to states such as Florida and Texas. Mass-scale immigration from south of the American border has changed coasts that were once sparsely populated, too. Florida’s population, in 1960, was just shy of 5 million; today, it is 20.6 million. Texas’s population has grown from 9.6 million to nearly 28 million over the same period.

Third, and relatedly, more people and higher incomes mean more property—and more valuable property—at risk. The CBO expects this trend to continue: Florida, for example, will account for 55 percent of future hurricane costs, followed by Texas, Louisiana, and New York. (Showing how imperfect such projections are, though, the 2016 analysis did not even mention Puerto Rico.)

Observers could consider this development an unalloyed good, and a product of the free market, if the U.S. government hadn’t unwittingly subsidized it through persistent distortions—a by-product of the growth of government throughout the twentieth century, as America sought to cope with a more complex, more populous country. Before 1950, Washington had few institutional mechanisms to deal consistently with disasters. But, as the CRS reported in a 2011 paper for Congress, “the approach to disaster relief changed from 1950 to 1979, transitioning from a largely uncoordinated and decentralized system of relief funding” led by states, cities, and towns, and private charities “to one dominated by the federal government.”

America had been groping toward a bigger role for Washington in disasters even before 1950. Hurricanes and floods have afflicted coastal Americans for as long as there have been coastal Americans, Native or otherwise. But the Mississippi River’s spring flooding of 1927, the 13th big U.S. flood since 1882, marked a turning point. Causing what then–commerce secretary Herbert Hoover called “the greatest disaster of peace times in our history,” the surge displaced 700,000 people and destroyed millions of acres of cropland, businesses, and homes. The flood also changed the way that people think about government’s responsibility toward individuals, says John Barry, a New Orleans resident and author of Rising Tide, the 1997 book that chronicled the flood. Public opinion was “absolutely overwhelming that the federal government had some responsibility to help.”

America mobilized historic aid. The Army, Navy, Coast Guard, and National Guard rescued 300,000 people. The Red Cross, a private relief organization, set up camps for more than 325,000 evacuees, complete with plumbing and electricity. “The Army provided tents, cots, blankets, and field kitchens,” the Red Cross notes in an internal history. The Red Cross raised $242 million in today’s dollars and, together with the military, would “rescue, house, feed, and clothe” hundreds of thousands of evacuees, “many of them for as long as ten months,” Barry wrote.

Looking to determine what it could do better to mitigate such events, the government created the first two pillars of modern-day storm aid. From this time on, it would have a larger role in immediate relief, though private-aid organizations such as the Red Cross still play a big role. On infrastructure, though, Washington radically changed its philosophy: the federal government, not individual states, would be mostly responsible for long-term flood-protection infrastructure, such as levees and flood walls. States had previously had to pay up to half the cost of construction. Now Washington, largely through the Army Corps of Engineers, took responsibility; state and local governments would maintain only levees, once built.

Washington changed its approach because powerful businessmen as well as regular voters wanted it, and not just in states prone to Mississippi River flooding. In September 1927, just months after the floods, the national Investment Bankers’ Association came out for flood control as a “national duty,” noting that 10 percent of America’s investors had interests in the Mississippi region, from farmland to shares in utility companies, the New York Times reported. Sidney Lewis, assistant state engineer for Louisiana, told the Times that the state could not handle its one-third share of flood control, having “exhausted the full limit of [its] sources of revenue.” Later that year, a Louisiana resident, calling for political action, noted that “each year, the waters from 31 states find their way to the great drainage ditch of a great, rich nation and strike terror in the hearts of people living behind sand dikes” and that “state monies are not adequate.” Subsequent floods in the Northeast and along the East Coast solidified national support. But Washington largely remained in the background on the final pillar of current-day storm assistance: long-term help for people to rebuild their houses. Of 32 engineers, bankers, and civic leaders queried by the Times after the 1927 disaster, only one suggested helping farmers—many of them subsistence sharecroppers or tenant farmers—“rehabilitate” their houses.

As Barry chronicles, Hoover tried to organize reconstruction efforts, cajoling Southern businessmen into creating nonprofit “reconstruction corporations” to lend money cheaply for rebuilding. But such efforts, “the only organized program for rehabilitation,” fizzled. The Red Cross, thanks mostly to its private donations, sent people home to rebuild as the water receded, armed with “two weeks’ supply of food and seed for a vegetable garden”—plus, “if their home had been destroyed, their tents and camp bedding.” A year later, the Times reported that “farm homes which were little more than piles of debris have been restored in magical fashion” but didn’t inquire how that had happened or who remained displaced. Private housing construction just didn’t fall within congressional or presidential jurisdiction.

In the postwar years, worries over nuclear conflict and heightened national attention to storms spurred Washington to take an even bigger role in providing relief. In 1950, lawmakers passed the Federal Disaster Relief Act, which established the modern framework for response: when a governor of a state or territory declares a disaster, the federal government steps in to alleviate acute conditions. Amendments to this law over decades culminated in the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), created by President Jimmy Carter in 1979 via executive order. FEMA, though, doesn’t take over from a stricken state; instead, it deploys resources—food, water, and temporary shelter—as directed by state officials, and sets up central stations, often in empty stores, where people can go to apply for long-term help. FEMA now picks up the tab for at least 75 percent of disaster-relief efforts, both immediate help and longer-term infrastructure rebuilding. In major disasters, it can shoulder an even greater share of the burden.

Even as Washington bureaucratized disaster management, though, lawmakers were slower to take on the responsibility for rebuilding private homes, through offering flood insurance to homeowners—something that they couldn’t obtain on the private market. Presidents Truman and Eisenhower floated the idea of government-subsidized flood insurance in the 1950s—ironically, to save taxpayers money: public officials thought that charging people premiums up-front would at least defray some relief costs; Truman saw insurance as “far superior to direct federal payments.” Flood insurance would be a short-term measure, to ease people’s relocation from dangerous areas, the president said. The flooded areas would not be redeveloped.

But Congress balked for more than a decade, heeding warnings such as this one in 1955, from a Times roundup of expert opinion: “general flood damage has been uninsurable—except for a few tries that ended in failure—from the time Noah rode out the deluge.” It wasn’t until 1968, toward the end of the Great Society program creation, that President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Flood Insurance Program into law. FEMA, which administers the program, now insures 5 million residential buildings in flood-prone areas, protecting residents against up to $350,000 in losses, including for the contents of a home. This figure encompasses more than 5 million individual homes, as FEMA also insures condominium associations with multiple units.

“FEMA, which administers the program, now insures 5 million residential buildings in flood-prone areas.”

Together, these two of the three pillars of modern disaster philosophy—disproportionate rebuilding help for state and local governments and for individual citizens, via flood insurance—have produced perverse results. Developers build in low-lying areas, encouraged by state and local officials who bear little of the cost of such unwise choices, while reaping a short-term benefit: bigger populations and higher tax revenues. FEMA has nearly 1.8 million flood-insurance customers in Florida alone, and another 608,000 in Texas—its two most heavily insured states. State and local governments have little incentive to plan neighborhoods around good flood protection, including levees, reservoirs, and natural swamps and drainage areas, as well as denser, higher housing.

In the decades before Harvey, for example, Houston approved the development of more than 10,000 homes in a floodplain, inside the very reservoirs that take in the water spillover when federal dams that protect older parts of the city reach capacity. As the Texas Tribune reports, most residents of the upper-middle-class neighborhoods built within the reservoirs seemed to have no idea that they were living in a dormant, man-made lake until Harvey inundated them with days’ worth of standing water last summer. The episode points up how federal incentives interact with the local imperative to build: the national flood-insurance program’s official flood maps put the reservoirs outside of floodplains, on the grounds that they are man-made “flood pools,” indicating to residents and their home lenders that it was safe to build, according to the Houston Chronicle. For that reason, mortgage lenders did not require homebuyers there to take out federal flood insurance, though residents have received temporary housing and other assistance after Harvey—and are now suing the Army Corps of Engineers for not deliberately flooding the area to protect its dams, exactly what the corps was supposed to do under the dams’ design.

Building unwisely puts all residents, old and new, at risk. As Samuel Brody, coastal-planning professor at Texas A&M–Galveston, points out, Houston has less permeable landmass—places where water can go—than anywhere else except Los Angeles. That means more flooding, as has occurred in the four historic rainstorms that have afflicted the city since Hurricane Rita lashed it in 2005, just after Katrina.

This problem won’t end until the government changes the distorting signals that it sends to the market. Washington must stop spending so much of its disaster aid in a way that encourages individuals, as well as state and local officials, to keep building in harm’s way.

Consider: of the $278 billion that Washington spent over the decade before 2015, the government spent $37 billion on flood-insurance payouts. The flood program racked up $22 billion in claims from Katrina and Rita in 2005, $15 billion after Hurricane Sandy, and still-untold billions over this past year. These figures understate the amount spent rebuilding private housing, as the government also distributed $24 billion in block grants to states, which used some of that money to help homeowners after storms. And just this fall, Congress forgave $16 billion in debt owed by the flood-insurance program. “The U.S. government has provided an unprecedented level of support for flood losses in recent years,” says Brian Schneider, senior director in insurance at Fitch Ratings, a bond-analysis firm.

As Washington protects private homeowners from loss, it neglects what it should be doing: working with state and local governments to build better public infrastructure. Overall, of FEMA’s disaster-relief fund, which constitutes about half of all federal disaster spending, 53 percent goes to helping governments replace what they lost and 22 percent to helping people rebuild. Only 7 percent goes to “hazard mitigation,” or prevention. The Army Corps of Engineers’ annual budget to build and maintain levees is just $4.1 billion—far less than the flood-insurance losses from this year’s storms.

Flood insurance is in obvious need of reform. “There needs to be some grandfathering” of existing policyholders as the government slowly raises premiums and refuses coverage for new properties in risky areas, says Barry, pointing out that many flood-prone residents “aren’t millionaires, but working-class people” in the energy, fishing, and tourism industries along the coast. “They have done nothing wrong.”

First, FEMA should stop covering second homes—19 percent of policies, according to a CBO report. Second, payouts should be means-tested; with median incomes of $75,000, policyholders are wealthier than their peers, says the CBO, and should pay higher premiums as well as higher deductibles before insurance kicks in. House prices, over time, would reflect such changes, decreasing as the potential for the loss of homeowner equity increases.

Coastal lawmakers will resist change. In 2012, Congress passed a bill to bring premium payments gradually in line with costs and to exclude particularly at-risk properties, including those with repeat past losses. (Congress also raised the deductible for losses, from $500 to $1,000.) But after an outcry from key lawmakers, Congress watered down some of these provisions—so to speak—in 2014. It did, however, keep the higher deductible. More recently, the House financial-services committee killed a proposal to eliminate coverage for homes worth over $1 million. The committee has also backed away from excluding houses with a history of past flooding, considering instead only future flooding, even though the past is helpful in assessing the future.

“Washington should back away from its practice of indemnifying states and cities for 75 percent of their disaster costs.”

As Washington must send a different message to homeowners and homebuyers, it must also change its signals to state and local officials and, indirectly, to municipal-bond investors. The federal government should back away from its practice of indemnifying states and cities for 75 percent of their disaster costs. Instead, Washington should offer more financing to support state and local governments that invest in better infrastructure to reduce flood risk—drawing some of these monies from funds previously used to rebuild and replace state and local infrastructure and private homes. Washington should also consider each region’s income and resources. New York and Houston, for example, have high personal incomes and thriving economies and don’t need billions of dollars in reconstruction money from poorer taxpayers elsewhere. As the CBO comments, federal aid “may underestimate a given state’s capacity to recover from a disaster using its own resources.” After Harvey, however, Texas’s governor, Greg Abbott, has resisted using the state’s $10 billion rainy-day fund to defray storm costs, even though the storm was, literally, a rainy day.

As municipal investors and advisors see states and local governments bear more long-term responsibility for their decisions, they would logically apply more scrutiny to local governments’ ability to withstand storms. As it is, taking into account current federal practice, “what we’re seeing, honestly, is that state and local governments tend to be pretty resilient when it comes to this,” says Stephen Winterstein, municipal-bond managing director at Wilmington Trust. “If you look back to Katrina and Rita in New Orleans, it’s taken years, but it’s recovered nicely,” he notes, and “Florida has been resilient with the hurricanes going back to Andrew” in 1992.

Similarly, Amy Laskey, managing director at Fitch, notes that while bond analysts always consider a municipality’s ability to withstand an emergency that lowers tax revenues or results in higher costs, they also see that “the federal government . . . comes in, private insurance comes in, they pay for a lot of repairs. The value of the assets that were damaged ends up higher, a perverse result in some cases.” With less federal support, investors would pay more attention to localities’ underlying economies and fiscal positions, as well as their more idiosyncratic but useful ways of protecting investors: Texas, for example, has a land-backed fund that guarantees $75 billion worth of school-district bonds in case of any eventuality.

Better incentives would mean better planning. Brody, the Texas A&M professor, doesn’t suggest that Houston start zoning as extensively as many cities do. “Zoning is traditionally separate land uses,” he says, with some areas set aside for homes and some for commercial buildings—and Houston doesn’t follow that model. Such zoning is less critical, however, than what he calls “spatially targeted development,” with many flood-prone areas simply off limits. Brody also suggests that Houston beef up its requirement for freeboard—the elevation of a house above sea level—from one foot to three feet. “Inches matter,” he notes, as keeping the usable part of a home above a flood zone avoids damage to much of the structure and contents of that home.

In letting state and local governments, as well as individual homeowners, take on more responsibility in recovering from predictable storms, the federal government could turn its focus to helping the constituents of weak and incompetent governments that subject people to sustained humanitarian crises after disasters. In Puerto Rico, nearly half of residents remain without power three months after the storm. Washington has done much to bring in emergency supplies, but the extent of what it can accomplish is limited, because Puerto Rico’s hapless government initially refused to do what all state and local governments do after such crises: call on other American power companies for reciprocal aid. Puerto Rico failed to ask for such aid until after a month had passed, exacerbating the immediate crisis and delaying longer-term recovery.

Puerto Rico’s plight is a reminder of 1927: the government’s most important job, after a storm, is humanitarian. Puerto Rico is now relying not only on the federal government but also on New York State and local government as well as nonprofit groups to help it accomplish the most basic tasks. It took weeks before Manhattan borough president Gale Brewer’s office settled on a task that wouldn’t duplicate what others were already doing. Brewer’s office has now helped New York–based Resilient Power Puerto Rico, a post-Maria relief project of the nonprofit Coastal Marine Resource Center, to send solar-power equipment to the island, powering a hospital emergency room and public kiosks where people can charge their phones. Washington should similarly concentrate less on insuring the contents of coastal middle-class homes and more on saving the lives of people going for months on end without power, water, and medicine.

Top Photo: A flooded home in Houston last summer after the hugely destructive and costly Hurricane Harvey (JULIE DERMANSKY/ZUMA PRESS/NEWSCOM)