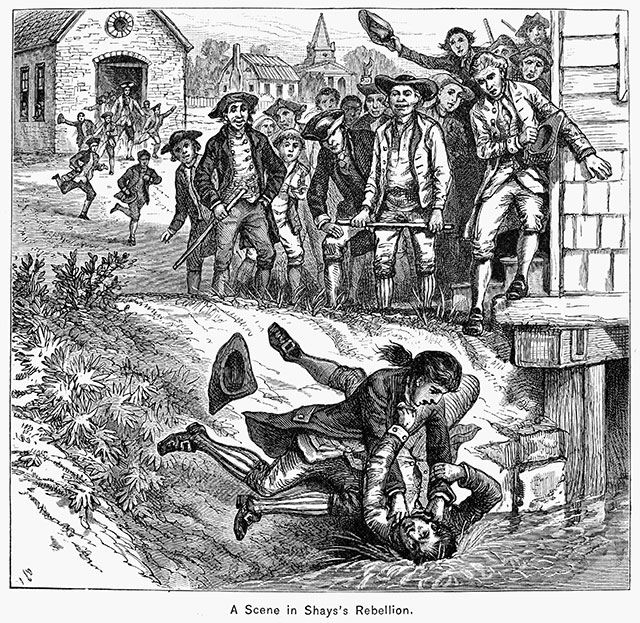

On January 26, 1787, 1,500 Massachusetts rebels marched on the Springfield Armory, intending to take the weapons and gunpowder stored there. The rebels came from local western Massachusetts towns and called themselves White Indians or Regulators, after the South Carolina vigilantes who had seized state courts and government in the 1760s. They wore sprigs of evergreen in their hats, just as they had during the recent War for Independence. They came home from fighting England to find their farms being taken over for debt by the courts, often sold for knockoff prices to speculators from Boston and other cities in eastern Massachusetts. The rebels were led by a local farmer and onetime captain in the Continental Army, Daniel Shays, who intended to get hold of the weapons in Springfield and, as he wrote, “march directly to Boston, plunder it, and . . . destroy the nest of devils, who by their influence make the Court enact what they please, burn it and lay the town of Boston in ashes.” The rebels, George Richard Minot wrote in his History of the Insurrections in Massachusetts a few years later, “had been led to think that they were contending against a power which would enslave them”—a rising aristocracy, supported by the cunning of dishonest lawyers. The rebellion was a reaction, Thomas Grover of Worcester wrote, to “a large swarm of lawyers . . . who [caused] more damage to the people at large, especially, the common farmers, than the savage beasts of prey.”

The government, on the other hand, feared the masses—which it dismissed as a dangerous mob, a manifestation of unfettered democracy, rather than the republic that most of the Founders had intended. Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin sent 1,200 militiamen to put down the rebels at the armory—an illegal act because the armory was federal, not state, property, and Bowdoin did not have permission from Secretary at War Henry Knox to do so. Like Shays’ rebels, many of the government’s troops were veterans of the War for Independence; unlike Shays’ rebels, the government troops wore white slips of paper in their hats. The militia, principally from the richer, eastern part of the state—from the areas surrounding Boston and Worcester—tended to be traditional Congregationalists; many of Shays’ rebels were Freewill Baptists, Universalists, Shakers, or radical anti-Federalists. Presbyterians dominated Pelham, Shays’ hometown. Easterners more often lived in the sophisticated cities, where they adopted leisure-class values, at least as compared with the homely virtues in western Massachusetts. The militiamen were paid a total of 6,000 pounds, borrowed from 150 or so wealthy merchants who lived in or whose livelihood depended on coastal towns, and from a few of the seven interrelated families—the River Gods—that resided along the Connecticut River. They were led by General William Shepard, a Massachusetts representative and a leader of the state militia.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

This civil war of farmers versus rich merchants—pitting neighbors against neighbors and splitting families—threatened the existence of the new American nation. The two sides were fighting a cultural war. Both considered themselves true Americans and saw their antagonists as anti-Americans—at a time when no one really knew what an American was.

At four in the afternoon on that January 26, in the fading light, in snow six inches deep, a militiaman, Thomas Dwight, saw Shays and his army coming from the north—probably along what is now Springfield’s State Street. Levi Shepard, a government supporter who was in Springfield when Shays’ men arrived, thought that Shays was “very thoughtful, and appears like a man crowded with embarrassments,” in contrast with other rebel leaders, whom he regarded as “insolent & imperious”—including Luke Day, whom some called the “master spirit” of the insurrection. The rebels stopped 150 yards from the government troops for a parley. According to historian David Szatmary, two of General Shepard’s men—William Lyman and Samuel Buffington—told the Shaysites that, if they advanced, “they would inevitably be fired on.”

“That is all we want,” Adam Wheeler, a rebel, said. Another rebel predicted that if the situation was “not settled before sunset, New England would see such a day as she had never yet seen.” Shays—sword in one hand, pistol in the other—sent a message back to Shepard: “I am here in defense of that country that you are endeavoring to destroy.” To his men, Shays said, “March, God damn you, march.” The rebels advanced.

Shephard ordered his men to shoot over the rebels’ heads. Shays and his men kept coming. Shepard ordered his men to shoot into the rebels’ ranks. Four rebels were killed; 20 more were wounded. Shays’ army retreated.

“Had Shays, the malcontent of Massachusetts, been a man of genius, fortune, and address, he might have conquered that state,” Oliver Ellsworth wrote in late 1787 in Hartford’s Connecticut Courant, “and by the aid of a little sedition in the other states, and an army proud by victory, become the monarch and tyrant of America.” The division between the rich and the rest in 1786–87 Massachusetts, with its all-or-nothing character, presages today’s nationwide political-social split. Shays’ Rebellion offers us a lens through which we can see our current polarization.

The rebellion had been brewing for years. Before the Revolution, western Massachusetts farms were self-sufficient. After the war was won, farmers and small tradesmen began wanting some of the luxuries that those in the eastern cities enjoyed—such as lace, furs, calico, and European investments—which enabled the eastern merchants, according to historian Stephen E. Patterson, to “expand their domestic market far beyond its limited prewar size. The Eastern merchants could aim to do more than satiate the pent-up demand of their former customers by making consumers of people who had heretofore perhaps only nibbled at the fringe of the consumer market.” Easterners bought or financed newspapers in the western part of the state, because, Patterson explains, they were “eager to spread the gospel of consumerism for a small advertising fee.” Citizens were becoming consumers. Self-reliance was becoming self-service.

Inflation, economic depression, and postwar speculation all took a toll on the American economy. London merchants who traded with the now-free colonies were unsure whether their American partners’ credit was any good. They demanded payment in specie—gold or silver—up front. As a result, the American merchants also demanded payment in specie from their customers, many of whom lived in western Massachusetts and had no gold or silver. Because the paper money that they held was debased, they could not pay what they owed to the merchants or the government. The state also taxed its citizens to clear its war debt, demanding these payments, too, in specie.

“I have been greatly abused, have been obliged to do more than my part in the war,” wrote one Revolutionary War veteran, who said that he had “been pulled and hauled by sheriffs, constables and collectors, and had my cattle sold for less than they were worth. . . . The great men are going to get all we have and I think it is time for us to rise and put a stop to it, and have no more courts, nor sheriffs, nor collectors nor lawyers.” “The extreme distress the people have suffered,” George Brock wrote in his 1786 Address to the Yeomanry of Massachusetts, refuted rumors that the inhabitants of western and central Massachusetts could pay their debts but were choosing not to. “Unless,” Brock wrote, “their . . . lordships are resolved that we should follow the example of the oppressed Irish and live wholly on potatoes and skimmed milk, I know not what method of support they have charted out for us.”

The Shaysites believed that the merchants were profiting from their misfortune. The merchants believed that the Shaysites, especially those who bought luxuries, often on credit, were lazy. John Quincy Adams saw the Shaysites as “malcontents [who] must look to themselves, to their idleness, to their dissipation, and extravagances.” The merchants, bankers, and land speculators believed that—for the farmers and small shopkeepers—gold and silver corrupted. Paper was less apt to do so. But they did not apply this principle to themselves. The rebels’ mirror image of the merchants and bankers and land speculators held, according to John Wise, an early supporter of the American Revolution, that specie inclined men to “[e]xtortion, dissembling, and other moral evils.” Both sides supported their beliefs by citing statistics and biblical authority. Both argued not economics, but morality. As the struggle became a war over values, each side damned the other for its immorality and bad faith—a familiar strain in American politics. Two conflicting worlds—or, at least, two conflicting myths—collided.

The farmers and shopkeepers in Massachusetts repeatedly petitioned Boston, asking the government to stop the courts from foreclosing until after the next election, in the spring of 1787, when they hoped that their pleas would be acted upon by a new and more sympathetic administration. If the courts were allowed to continue foreclosing, half the people of the affected counties might go bankrupt. Since the vote was limited to white men of property, the rebellion wasn’t just about losing money; it was about becoming a political nonperson. Losing one’s farm or home or shop could disenfranchise a citizen.

In August 1786, the people, especially of western Massachusetts, had called for conventions to deal with the crisis. In the fall, farmers stopped the courts from acting in Worcester and other towns to the west like Northampton, where hundreds of hill-country farmers and shopkeepers blocked court officers from entering the courthouse. Court was adjourned to the home of local innkeeper Captain Samuel Clark, where it met with a six-man delegation, which reiterated the demand to dismiss the courts until a solution to the crisis could be worked out.

In Boston, Governor Bowdoin and his supporters ignored the calls for conventions, though it was no secret that, in some cases, the militia was sympathetic to the dissenters. The situation deteriorated. In Concord, uncomfortably close to Boston, the rebel Jeb Shattuck marched a crowd of antigovernment sympathizers armed with clubs and muskets and swords. They surrounded the town courthouse. Ninety insurgents peeled off to a local tavern to confront the judges gathered there; the judges slipped out a back way into the night. In Great Barrington, in the Berkshires, 800 farmers prevented a court from sitting and, raising the ante, freed debtors from prison.

The conflict culminated in Springfield, the largest town in western Massachusetts, where the Supreme Court was expected to indict rebels who had prevented other courts from sitting. The governor ordered 600 militiamen to protect the court. The rebels announced that they would shut it down. Their leader was Daniel Shays.

Shays first stepped onto history’s stage on October 17, 1786, when he was elected a delegate to a convention in Hadley that supported rebels fighting for local control. He was a patriot who had loaned money to the Revolution. He fought at Lexington and Concord and Bunker Hill. He was a captain in General Rufus Putnam’s Third Massachusetts Regiment, brave enough for the Marquis de Lafayette to honor him with a ceremonial sword. (Shays’ enemies would claim that Shays sold the sword.) In October 1780, after being wounded, Shays—on his own request—was discharged from the American army so that he could return to Pelham, where he struggled to keep his farm, trying and failing to build a windmill. The farm, said a visitor in January 1787, was “a sty, it having more the appearance of a den for brutes than a habitation for men.” But a nineteenth-century photograph shows a farmhouse like other farmhouses, a Cape Cod–style building, two windows and a door in front, one chimney, and an extension in the back. The truth didn’t fit with the myth.

The government issued writs, including suspension of habeas corpus, which gave the governor power to declare martial law. Boston passed the Riot Act, which held government officials guiltless for killing rioters. “I had rather be under the Devil than such a Government as this,” said Isaac Chenery of Holden, a doctor.

The uprising did not go unnoticed. “The commotion[s] . . . in the Eastern States . . . are equally to be lamented and deprecated,” George Washington wrote to Henry Lee on October 31, 1786. “They exhibit a melancholy proof of what our trans-Atlantic foe [England] has predicted”—that the now-free colonies would fail at self-government. Washington worried that “mankind, when left to themselves, are unfit for their own government.” After the rebellion had ended, writing in the New York Independent Journal on November 14, 1787, in an essay that would become Federalist 6, Alexander Hamilton opined: “If Shays had not been a DESPERATE DEBTOR, it is much to be doubted whether Massachusetts would have been plunged into a civil war.” Several years later, Hamilton wrote Washington that “Massachusetts threw her Citizens into Rebellion by heavier taxes than were paid in any other State.” Not that Hamilton was sympathetic to the rebels; on the contrary. Sometimes, he wrote in Federalist 28, the only remedy for emergencies is force. Shays’ Rebellion was considered a contagion, a transmittable sickness. The body politic was “liable to violent diseases,” Noah Webster wrote. “If all men attempt to become masters . . . most of them would necessarily become slaves in the attempt.”

After the confrontation at the Springfield Armory, General Shepard wrote to Governor Bowdoin that “the unhappy time is come in which we have been obliged to shed blood.” Shepard bragged that, if he had wanted, he could have killed most of the rebels in 25 minutes. The beaten rebels ran to sympathetic towns, like Pelham, Shays’ home, where Shays and his men took a stand on two hills. They were followed by General Benjamin Lincoln, the former (and first) Secretary at War of the new United States. Shays asked for a parley; Lincoln told Shays to surrender. Shays treated Lincoln’s messengers with respect, but he demanded pardons for all. During the hiatus in fighting, Shays evacuated his troops 30 miles away, to Petersham. Many of Lincoln’s militia had signed up for only a month’s tour, ending on February 21. The militiamen looked forward to the end of their service, just as the government was about to break the rebellion. Lincoln was running out of time.

Then a blizzard hit. “The wind and snow seemed to come in whirls and eddies,” wrote soldier Thomas Thompson, “and penetrated . . . my clothes and filled my eyes, ears, and neck.” Lincoln forced his soldiers to march overnight in waist-high, even shoulder-high, drifts. His militia captured 150 of the surprised rebels. The rest, including Shays, scattered. “The principal incendiaries have unluckily made off,” James Madison wrote to Edmund Pendleton on February 24.

The final battle of Shays’ Rebellion happened on February 25, in nearby Sheffield. The militia routed the rebels. The uprising was over.

Lincoln spent the next few days hunting down the remaining insurgents. A few troops formed under other rebel leaders, but there were only skirmishes through the spring—and some acts of revenge against the government loyalists. Josiah Woodbridge’s Hadley potash works were torched. Westfield and Greenfield reported cases of arson. Rebels marched on New Lebanon, where Lincoln was resting at a hot springs. Lincoln fled. The rebels moved on. There were attacks against Shepard and his property. One of his horses was mutilated, ears cut off, eyes gouged out. In April, Shepard received a letter in which someone threatened to kill him.

The government had to face the question of what to do with the rebels. How to heal the breach between the two still-passionate sides of the rebellion, especially now, after the two sides had fired on each other and first blood lay red on the snow? How could the two sides ever again join together as citizens of the new country?

The government decided to pardon most of the rebels, but for Shays and about a dozen others. Shays, who had already gone into hiding, was sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of Massachusetts.

If the rebels were too severely punished, George Washington said, they might continue to be a dangerous minority. Solidarity could come only from a lenient policy. “[T]here will be sometimes disorders in the very best of governments,” he wrote. And, if the government “keep[s] the mass of people in profound ignorance, [it] must abide the consequences when the body politic is convulsed.” Madison agreed with leniency, writing to Jefferson that the rebels should be disenfranchised for a time and made to take loyalty oaths.

Jefferson, as usual, sympathized with the rebels. “I like a little Rebellion now and then. It’s like a storm in the atmosphere,” he wrote to Abigail Adams, arguing that the insurgents should be pardoned. “[C]an history produce an instance of a Rebellion so honorably conducted?” he asked, wondering “what country can preserve its liberty if the rulers are not warned from time to time [by] . . . the spirit of resistance.” And he famously, or infamously, declared: “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

Nearly two months after the final battle of Shays’ Rebellion, on April 16, 1787, Madison wrote to Washington that the conflict in Massachusetts would “[n]o longer be [decided] by sword but by a trial of strength in the field of electioneering.” By then, most of the rebels had been allowed to take loyalty oaths, pay a fine, and go home. But no pardons were offered to Shays and the other leaders of the rebellion. Not yet, anyway—Shays was still missing.

As the election for a new Massachusetts governor approached, sympathy for the rebels encouraged John Hancock to run again. He had left office in 1785 but thought that Bowdoin had mishandled the rebellion—and was loading the dice in his own favor by trying to purge voter rolls, especially of Shays sympathizers, who had either lost their property and thereby become disenfranchised or who still owned their farms and shops but had sided with the rebels, becoming disenfranchised in that way. If allowed to vote, they could likely swing the outcome.

The spirit of rebellion “operated powerfully in the late Election” in Massachusetts, John Jay wrote to Jefferson. Hancock won easily.

The leaders of the young American republic feared that the dispossessed and dissatisfied in other states would follow Shays’ example. Madison said that the rebellion was one of the “ripening incidents” that spurred the calling of a convention to write a new constitution for the United States. He pointed out that Massachusetts “can not keep the peace one hundred miles from her capitol” and warned that “[t]he insurrection in Masst [sic] admonished all the States of the danger to which they were exposed.” John Marshall, who would become the fourth chief justice of the Supreme Court, worried that what had happened in Massachusetts could lead to a second American Revolution. On May 25, 1787—with some Shaysites still on the run and passions on both sides still hot—delegates from around the new United States (except from Rhode Island) met in Philadelphia to replace the Articles of Confederation, which had created a weak federal government, one unable to handle domestic affairs, including insurrections like the one in Massachusetts. A new founding document could also prove to Europe that America was not a third-rate republic. Hamilton believed that the new country should “beware of extremes” and avoid equally “the convention and the bayonet.” In Massachusetts, they had tried the bayonet. In Philadelphia, they would try the convention.

Some of the leaders in the recent War of Independence began to moderate their enthusiasm for uprisings against authority. Elbridge Gerry (who would become the fifth vice president of the United States) said that he had “been too republican heretofore: he was still however republican, but had been taught by experience [including Shays’ Rebellion] the dangers of the leveling spirit.” Others worried about a too-powerful central government. A few suspected that the convention would eliminate state governments altogether. At the time, what went on in the convention was secret, but according to Madison’s subsequently published Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, the convention was concerned with the influence of Shays’ Rebellion; with “commercial discord” among the creditor and debtors; and [with] “the havoc of paper money.”

Madison believed that citizens must be protected against their rulers but equally that they should be protected from themselves—against “transient impressions into which they themselves might be led.” A minority of voters, Madison warned, just a third of the electorate—if skilled and motivated—“may conquer the remaining two-thirds.” Just a third of those who “participate in the choice of rulers may be rendered a majority by the accession of those whose poverty disqualifies them from suffrage, & who for obvious reasons may be more ready to join the standard of sedition than that of the established Government.” What could prevent a passionate minority such as the Shaysites from usurping an apathetic majority—limiting government to Hamilton’s rich, well born, and able, or educating and empowering Jefferson’s vast country of independent farmers? The “obvious precaution agst [sic] this danger wd be to divide the trust between different bodies of men, who might watch & check each other,” Madison wrote.

Article II, Section 2 of the proposed Constitution gave the president the “power to grant reprieves and pardons for offensives against the U.S. &c.” The delegates could not ignore how Massachusetts had pardoned Shays’ rebels. Edmund Randolph of Virginia, who would become the nation’s first attorney general, pointed out that the presidential pardon could be used “except [in] cases of treason.” But this seemed “too great a trust,” Madison quotes Randolph as saying. “The President may himself be guilty. The Traytors [sic] may be his own instruments.” On the other hand, Rufus King of Massachusetts suggested that a legislative body was “utterly unfit” for impeaching and prosecuting a president. “They are governed too much by the passions of the moment,” King said. “In Massachusetts, one assembly would have hung all the insurgents in that State: the next was equally disposed to pardon them all.” He suggested, instead, “the expedient of requiring the concurrence of the Senate in Acts of Pardon.”

On September 17, 1787, the Constitution was adopted. On June 21, 1788, it was ratified. Shays—still undercover—haunted the Constitutional Convention. He haunts us today.

For decades, Shays’ Rebellion was dismissed as anarchy. Abigail Adams regarded Shays and his followers as “[i]gnorant, restless desperadoes, without conscience or principles, [who] have led a deluded multitude to follow their standard, under pretense of grievances which have no existence but in their imaginations.” Pennsylvania Founding Father James Wilson saw the rebellion as a disaster narrowly averted. “[W]e are not in the millennium,” he said, but “I believe it is not generally known, on what perilous tenure we held our freedom and independence at that period.” Even stalwart revolutionaries like Samuel Adams blanched at the example of Shays. Rebelling against a king was one thing, Adams believed, but “the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death.”

Jefferson, again, saw it differently. “I own I am not a friend to a very energetic government,” he wrote to Madison in late 1787. “It is always oppressive. The late rebellion in Massachusetts has given more alarm than I think it should have done.” In time, the Jeffersonian point of view would gain more adherents. More than 200 years later, both leftists and rightists claim Shays as their political ancestor. Both have reason to do so, even if the subject of their inspiration remains a dimly remembered, let alone understood, figure in American history.

After the rebellion’s defeat, Shays moved from town to town under various aliases, swearing never to be taken alive. He sought refuge in New Hampshire and Vermont. He petitioned for a pardon and, in 1788, received it—along with, eventually, a pension for his army service—and settled in New York’s Schoharie County, west of Albany, where some predicted that he would live the rest of his life in poverty and squalor. Instead, he seems to have become a success—and a Federalist. During the July 4 celebrations in 1803, he joined in a toast to “Alexander Hamilton and the Constitution,” which his rebellion may have helped create.

Top Illustration: Daniel Shays (CHRONICLE / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)