The rebuilding of the World Trade Center site has gotten everyone talking about architecture, but so far it's a one-sided conversation, as if the only question worth discussing is: What kind of modernism do we want? The graceless modernism of Daniel Libeskind's brutal and exhibitionistic "master plan"? The suave modernism of David Childs's valiant (but hopeless) effort to transform that plan's tallest building into a silk purse? But since we've now had 50 years of modernism here in New York, and only a half-dozen good buildings among hundreds of awful ones to show for it, maybe what we really want now is . . . not modernism.

Think of modernism and you think Houston, maybe, or office parks from Cherry Hill to Cupertino. But not New York. Gotham is the city of the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, New York trademarks, emblazoning the T-shirts that tourists take home from the Times Square souvenir shops. New York is the Plaza Hotel, the Flatiron Building, the old Bankers Trust and Equitable towers, the RCA Victor Building soaring over Saint Bartholomew's Church, the Sherry-Netherland, the San Remo. If Chicago takes the palm for inventing the skyscraper, New York can claim to have brought it to full flower. The classical skyscraper is one of Gotham's gifts to the world, the urbane expression of its technical genius, wealth, and confident cosmopolitanism.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

But when the dour Swiss Le Corbusier warned, "Beware the American architect"—meaning the New York skyscraper geniuses—the whole world, New York included, instantly hunched up its shoulders and took notice. Out with columns and cornices, out with decoration, even when it was as jazzy as the RCA Victor Building's dazzling bolts of electricity or the Waldorf-Astoria's sleek domes. Now we would have the grid-clad box of metal and glass, a machine for living, with form following function and no fussy and sentimental gewgaws.

You can see the initial appeal of the brave new world of no-nonsense industrial efficiency; but now, looking backward, there is a hint of something not just antihumanist but antihuman in the project, a whiff of totalitarianism. The grid bespoke faceless regimentation, the absorption of the individual into the relentless bureaucratic system, the effacement of all the quirky whimsy that makes us not just Man in the abstract but distinct selves with the unique identities that are part of what make us human. No wonder that today Le Corbusier's towers-in-the-park ideal exists in its purest form mostly as welfare-state housing projects, inhuman slabs in desolate wastelands, housing man not, shall we say, at his highest pitch of development. A machine for living: but what kind of life?

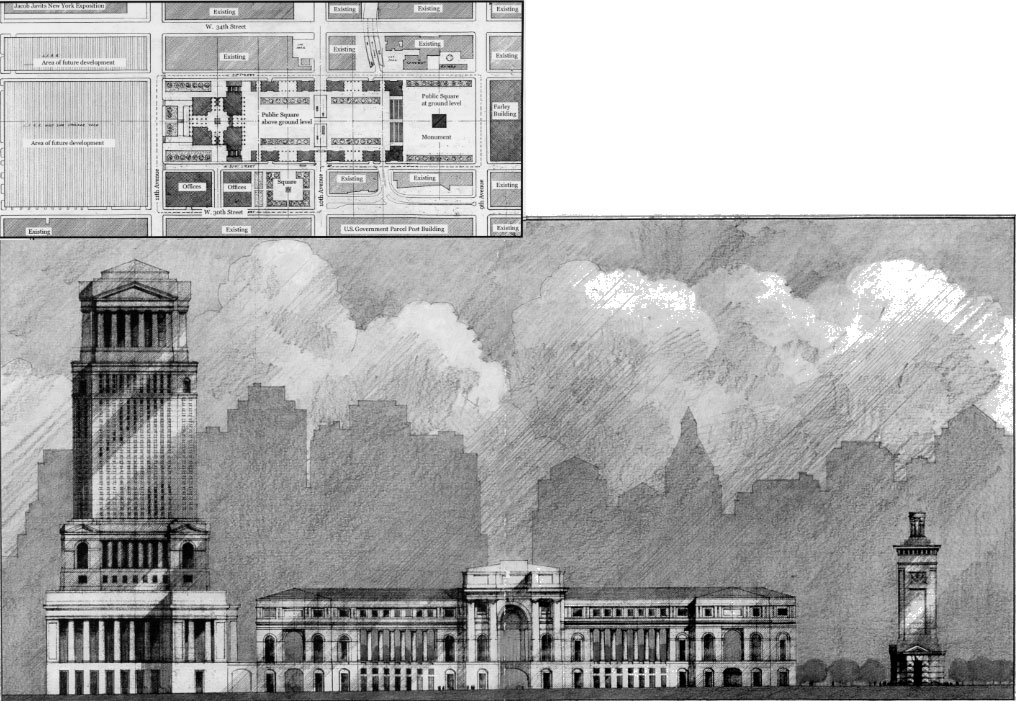

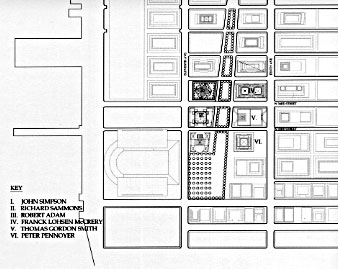

Well, the rebuilding of the World Trade Center site is a lost opportunity; but New York suddenly has another chance to move beyond the stale, seven-decade-old cliché of the endlessly repeated glass box, or the glass box twisted, deconstructed, or otherwise contorted as much by computer-design programs as by any human imagination. The City Planning Commission has proposed re-zoning for redevelopment a vast area of the Far West Side—more than 60 blocks from Seventh to Twelfth Avenues and from 30th to 43rd Streets. At the center of this redevelopment, an area now mostly of parking lots, rail yards, low-rise garages and repair shops, and the tangle of approaches to the Lincoln Tunnel, the planners envision a new boulevard, running between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues, and zoned for massive office buildings suitable for major corporate headquarters. For this north-south street, called Hudson Boulevard, City Journal has asked six renowned architects to design a half-dozen truly postmodernist buildings, skyscrapers that bypass modernism's dead end and bring New York's long and vibrant tradition of classical tall buildings triumphantly into the twenty-first century.

What do we hope to achieve by this project? First, we wanted to get traditionalist architects thinking about skyscrapers again. For decades, the glass box has been the only kind of skyscraper constructed, so much so that traditional architects haven't even bothered submitting proposals to design them. They have built magnificent low-rise buildings of every description, from sumptuous country houses, rivaling in harmony of proportion and exquisiteness of detail anything that the great Georgian architects created, to office developments that look like an entire classical urban square to new college quadrangles and churches. But of the tall buildings that define a city—and that set the direction of the entire architectural profession, because of the money, prestige, and visibility involved—they have built very few.

Second, we wanted to show real-estate developers and the corporate chiefs who rent their space that they have an alternative to the same-old, same-old that claims to be up-to-the-minute and daring and cutting-edge but has been timid and established orthodoxy for decades. Very few of these distinguished people live in modernist houses, because like everyone else, they don't much like the style. They live in Tudor or Georgian mansions, or in penthouses with Adamesque doorways and classical moldings. Even when you go up to the CEO's suite at the top of a modernist tower, you often enough find, amazingly, a fire crackling in the neo-Palladian fireplace and museum-quality eighteenth-century furniture—or, in the lawyers' offices, miles of mahogany paneling and molding, and ersatz versions of the CEO's originals, as if we were in the Inns of Court. But in choosing their architects, a herd mentality takes over. Everyone suffers agonies of mortification that he'll seem a trailer-trash rube if he says out loud the plain truth that the modernist emperor has no clothes. So up go the glass boxes, the safe, conventional choice.

In a world where McMansions with Venetian windows and "Great Rooms" are springing up in every suburb, this knee-jerk reflex may not even be such a good business decision anymore. One of City Journal's distinguished architects, John Simpson, is building New York's first new classical stone building in 60 years on East 95th Street—an extension of an existing beaux arts townhouse, to make a single structure that will then be sold off as condominium apartments. The developer had originally hired an architect to plan a modernist extension, but realized she couldn't make the project profitable. Only classical apartments would, as the developers say, "pencil out."

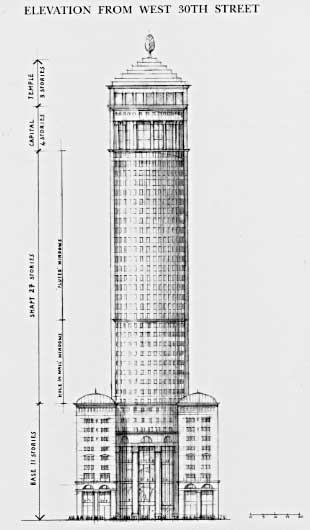

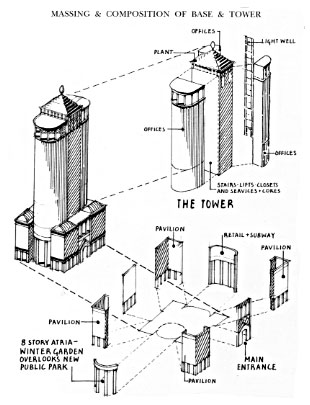

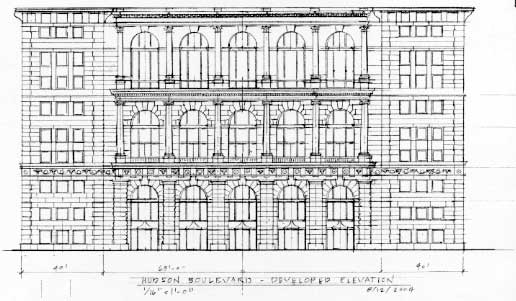

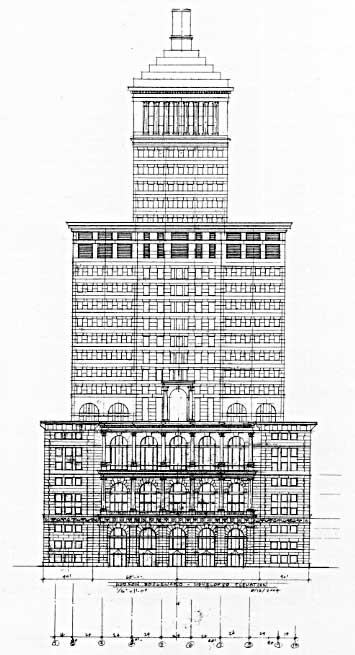

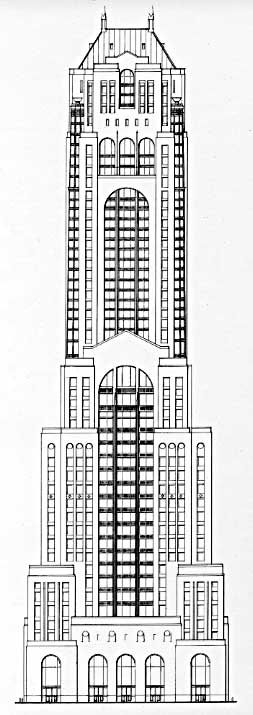

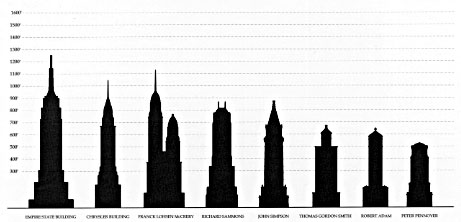

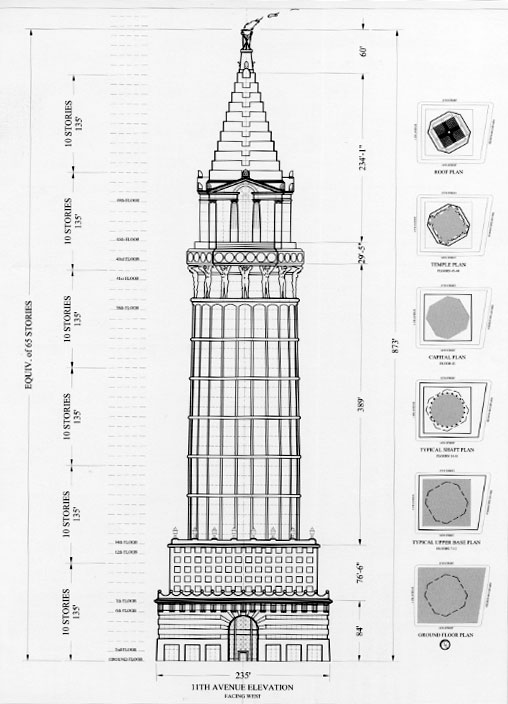

We asked each of our architects to pick a Hudson Boulevard site and design a major office tower that meets that site's specific zoning requirements. The result is a half-dozen extraordinary buildings, each memorably original, and all forming a harmonious ensemble, since they abide by some basic rules of urban civility. While these are very big buildings, ranging from 45 to 70 stories in height and offering the large, uninterrupted floor areas that modern corporations want, they bring a human scale to their monumentality. At ground level, they present urbanely welcoming street fronts, grand without being overpowering, with a progression of interesting shop windows. They break their facades into clearly articulated sections, developing and transforming as they rise and offering a visual interest that draws the eye skyward. And what a skyline they compose, with domes and pyramids of copper, brass, limestone, and gilding. This is a skyline that would be a daily inspiration to New Yorkers—and that tourists would wear on their sweatshirts.

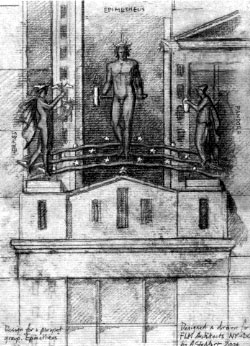

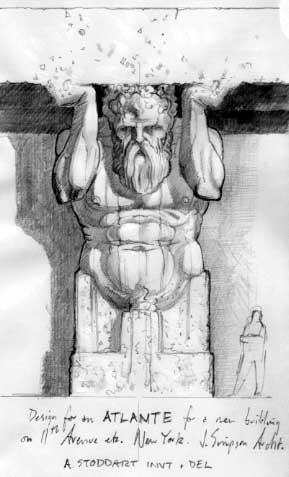

The mostly limestone facades, durable and restrainedly luxurious, are pure emanations of the New York skyscraper vernacular tradition. There's ornament in columns and cornices, rustication and pilasters, urns, anthemia, and pediments, with temples and colonnades high in the sky, topped by spires and finials. And two of the buildings have sculptures by Alexander Stoddart (arguably our greatest living sculptor). He has designed atlantes to support the temple at the top of John Simpson's towering column, and an art-deco-inspired grouping of gods and titans for the pediment midway up Franck Lohsen McCrery's building.

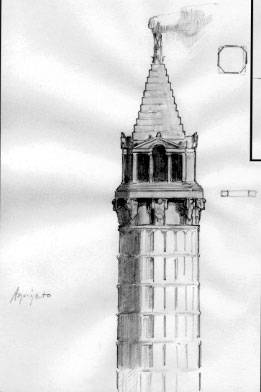

All of our buildings have inventive and eye-catching shapes. On the west side of the boulevard, Robert Adam, designer of Oxford University's Sackler Library, envisions a columnar tower that rises out of copper-domed pavilions and culminates in a stepped pyramid. Richard Sammons, who has built country houses and townhouses from Hong Kong to Florida, has designed a suave limestone and glass tower, whose telescoping setbacks, facade articulation like a ballerina's plié, and rounded glass corners on its upper half give it a remarkable lightness and powerful upward thrust. Just to the north, John Simpson, architect of the breathtaking Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace, has transformed familiar classical motifs into something entirely unprecedented—a column of glass, complete with fluting, rising from a limestone base and culminating in an exuberant pyramid-topped temple, rotated diagonally to the base.

On the east side of Hudson Boulevard, the buildings similarly grow higher from south to north, promising a remarkable urban vista from the public park at the south end of the entire project. Peter Pennoyer, who has built lavish country houses from coast to coast, imagines a serenely elegant tier of limestone temples, surprising for the powerful tension of its combination of chaste restraint with its profusion of colonnade upon colonnade. One block north, Thomas Gordon Smith, who is designing a new space in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum and whom a recent adulatory profile in the New York Times described as "a celebrity architect," raises his tripartite building upon a base that is a nine-story-high, beautifully detailed Italian palazzo—dramatically diverging from its forebears, however, in that it curves inward, embracing the visitor in the concave public space it forms.

Still farther north, the firm of Franck Lohsen McCrery, whose projects range from a sumptuous stone country mansion in Virginia to a remarkable vaulted chapel in South Dakota (and whose staff created the computer models of our project printed here), proposes a building whose consummately urbane twin towers, with their vast expanses of glass, soar almost effortlessly to the gilded domes that crown them.

We have carefully followed the Planning Commission's proposed guidelines; but we end with a suggested modification to accomplish with verve and brilliance something the planners forgot to do—getting pedestrians over to the new development from the new Penn Station to be built in the Farley Post Office building. Peter Pennoyer has designed, just across Ninth Avenue from the post office, a public square from which flights of steps rise to a block-wide colonnaded bridge, containing a public park and spanning Tenth Avenue with a triumphal arch to terminate at Pennoyer's tower, now moved just east of Eleventh Avenue. Not only would the plan create a stupendous new public space, but the tower would gracefully terminate the vista looking west from the new Penn Station and looking south down Hudson Boulevard—a supremely sophisticated urbanistic gesture.

If the planners' dreams come true, virtually a new city will arise on these 60 blocks, containing 12 million square feet of residential space and 28 million square feet of offices for 150,000 new workers—in itself one of the nation's largest business districts. This should be a free-market project, with private developers putting up the buildings as the market needs them, not some state-capitalist boondoggle whose burden on taxpayers will ensure that no economic growth will ever take place to fill the new buildings. All the government needs to do, beyond the re-zoning, is to extend the Number 7 subway to get workers to their new offices. Nor do we think that officials' fantasies of building a new football stadium and convention center extension to the west of this project—occupied only occasionally, forming a forbidding wall of concrete and glass for 12 blocks along Eleventh Avenue, and cutting the new development off from the Hudson River a block away—would foster the kind of upscale development they hope for, but would rather abort it. But we do know that every time New York has a long boom, lack of sufficient office space cuts it short before it can add permanent new jobs to the economy. The new zoning proposal aims to fix that; and as conditions warrant, we invite developers to pick our plans off the shelf and start construction.

If you build it, they will come.

—Myron Magnet