Every ten years, after the U.S. Census releases its latest population reports, most of the 50 states begin the complicated process of drawing new election districts. As you might expect, partisan bickering and maneuvering inevitably distort things. So a decade ago, Arizona voters decided to end the partisanship by removing the redistricting process from the state legislature and placing it in the hands of an independent commission. Last year, the new commission, consisting of two Democrats, two Republicans, and a nonpartisan chair, got to work on its first set of maps after the 2010 census.

Unfortunately, the results were anything but nonpartisan. The independent chair sided consistently with the two Democrats, essentially giving them control over the makeup of the congressional and state legislative maps. Lawsuits were launched, along with a push by Arizona’s Republican governor, Jan Brewer, to impeach the chair. The new maps, if let stand, “could reshape the state’s political landscape” in the Democrats’ favor, the Arizona Republic reported. Already, state lawmakers are looking at doing away with the commission or significantly changing it.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Arizona isn’t alone. In many states, including those where reformers had tried to make the process less political, redistricting has already determined the outcome of this year’s races for Congress and state legislature. In part, blame naivety for the reformers’ failure: redistricting isn’t easily drained of partisanship. But federal election law—especially the Voting Rights Act, which mandates a certain amount of legal gerrymandering to reach preferred racial outcomes—shares some of the blame. Though some states are inching toward ways of carving out fairer, less politicized electoral maps, reform is slow, and scheming over election districts remains nearly as important as it ever was to politicians’ fortunes, the composition of state legislatures, and even control of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Controversy over redistricting is almost as old as America itself. The word “gerrymander,” which describes an oddly shaped district drawn to gain electoral advantage, first appeared in print on March 26, 1812, in the Boston Gazette. The paper used the term to describe a district in Essex County, drawn by Massachusetts’s ruling Democratic-Republican Party, that looked like a salamander. Governor Elbridge Gerry had signed into law an electoral map incorporating the strange district—hence the portmanteau word.

Gerrymandering has persisted partly because the U.S. Constitution is silent about redistricting, so courts have had trouble ruling on the constitutionality of obviously partisan districts. “The Constitution no more regulates gerrymandering than it regulates pork-barrel spending or the many advantages of incumbency,” write two legal scholars, Larry Alexander and Saikrishna Prakash, in a 2008 William and Mary Law Review article. It’s true that in 1986, the Supreme Court tried to define excessively partisan gerrymandering, using terms like “fairness” and “discriminatory intent,” and to label it unconstitutional. But in a 2004 ruling, the Supreme Court admitted that the language of the 1986 decision had resulted in nearly two decades of confused rulings and fruitless efforts at consensus by lower courts. Justice Anthony Kennedy noted that “ordering the correction of all election district lines drawn for partisan reasons would commit federal and state courts to unprecedented intervention in the American political process.”

The court’s shift raised the stakes in the 2010 elections in a way that went largely unnoticed. Now that the courts were much less likely to intervene to prevent partisan redistricting, the winners of the 2010 elections would have fewer checks on their power to draw districts for the next round of elections, in 2012. Illinois governor Pat Quinn’s narrow defeat of Republican challenger Bill Brady, for instance, meant that Democrats would dominate redistricting in the Prairie State—a crucial component in any Democratic effort to retake the U.S. House of Representatives this year.

Clashes over redistricting in Illinois and Texas illustrate how much is at stake. A decade ago, federal judges intervened to break a Texas redistricting stalemate by drawing a map that largely maintained the status quo. The GOP argued fruitlessly that the new map was unfair, observing that Republican candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives had captured 57 percent of the Texas vote in the previous election but actually held just 15 of the state’s 32 House seats. So when Republicans took control of the state’s legislature in 2002, they engineered a new map that helped them win a 21–11 edge in congressional representation in the 2004 elections, strengthening the national GOP’s hold on the House. Democrats challenged the map, saying that states couldn’t have more than one redistricting per decade, but the Supreme Court ruled that nothing in the Constitution prevented it.

The 2010 census brought Texas a population gain of nearly 4.3 million, giving the state four new congressional seats. Republicans carved new maps that could, some observers estimate, give them victories in 26 congressional districts this year. But Democrats, joined by some civil rights groups, sued, charging that the maps failed to provide enough electoral opportunities for Latinos, who were driving the state’s population gains. A three-judge federal panel agreed, threw out the GOP maps, and instituted its own, which swung the balance back toward Democrats. The U.S. Supreme Court then threw out those maps, concurring with the one dissenting judge on the panel, who had called them “a runaway plan that imposes an extreme redistricting” on Texas. The state is currently in electoral turmoil: it has pushed back its primaries once already while the parties try to work out a compromise. Control of the House of Representatives may hang on the resulting map.*

With Texas’s outcome uncertain, Democrats have intensified the redistricting battle in Illinois, a state where Republicans picked up four congressional seats in 2010 and today hold an 11-to-eight advantage. Democrats control the state legislature, however, which meant that last year they could draw a redistricting map that will swing the House delegation to the left: heavily Democratic districts within Chicago have been merged with suburbs, ending the Republican advantage there. Democrats could win 11 or 12 seats (out of 18 now, after the state lost a seat in the latest census) under the new arrangement, experts predict. Republicans are protesting the redistricting; so are Hispanics, who say that it minimizes Latino population gains. But their objections have failed to get the map overturned in court.

Good-government advocates have decried such partisan mapmaking by state legislatures, but independent redistricting commissions and nonpartisan referees have proved equally controversial. In 2008, for example, California’s Proposition 11 put state legislative redistricting in an independent commission’s hands; two years later, Proposition 20 gave the commission power over congressional redistricting as well. But Democrats hijacked the process, according to a series of investigative articles on the websites Calwatchdog and ProPublica.

Here’s how they did it. The commission was supposed to be composed of 14 citizens—five Democrats, five Republicans, and four nonaligned members. But Calwatchdog reported late last year that one of the nonaligned commissioners, Gabino Aguirre, actually had a long history of associations with the Democratic Party. Not only had Aguirre made campaign contributions to Democrats; he had been active in left-leaning groups like the Coastal Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy, an organization with strong ties to the Service Employees International Union, which represents 700,000 California government employees and is a mainstay of Democratic politics in the Golden State. Investigators for the commission’s selection process either missed those associations or ignored them. Aguirre, supposedly one of the four independent members on the commission, helped crucially to tilt it toward the Democrats.

The commission was supposed to hear testimony from ordinary citizens and from local groups and then draw reasonable new maps, ignoring how they might affect the political fortunes of incumbents. Democrats immediately went to work on influencing the testimony—an effort coordinated, says ProPublica, by Alexis Marks, the deputy director of the House of Representatives’ California Democratic delegation and a federal government employee. “Democrats surreptitiously enlisted local voters, elected officials, labor unions and community groups to testify in support of configurations that coincided with the party’s interests,” reported ProPublica. “When they appeared before the commission, those groups identified themselves as ordinary Californians and did not disclose their ties to the party.”

In one particularly egregious case, early drafts of maps showed that incumbent Democratic congresswoman Judy Chu would wind up in a new district tilted against her reelection. Then a group calling itself the Asian American Education Institute jumped in. Testimony submitted by the group’s spokesperson, Jennifer Wada, argued that the district wouldn’t sufficiently represent Asian interests. But Wada never revealed that she was a registered lobbyist or that the institute, whose tax records show that it had no full-time employees, was working with a Democratic political consultant to influence the mapmaking. The commission accepted the group’s recommendations and gave Chu a district that firewalled her incumbency.

The maps that the commission produced will hand Democrats big wins in Sacramento, tilting the state senate at least two-thirds in their favor. They will also get a windfall in Washington, D.C. Examining population changes around the state, experts had initially predicted that no party would gain significantly on the federal level from redistricting. But the commission’s new maps, says ProPublica, will probably give Democrats six or seven extra House seats “in a state where the party’s voter registrations have grown only marginally.”

Similar maneuvering brought Democrats a victory in Colorado, another state where an independent commission, instituted by statewide referendum, controls redistricting. The state’s 2011 redistricting commission consisted of five Democrats, five Republicans, and one independent—Mario Carrera, an executive at Entravision, which operates Spanish-language TV and radio stations. Early on, Carrera sided with the Democrats in producing a plan that pitted a number of Colorado’s Republican state legislative leaders against one another in new districts. The state’s supreme court rejected the plan, ruling that it violated a provision of Colorado law that requires new districts to respect town and county lines and not split too many of them into different districts.

When the commission went back to the drawing board, Carrera, its chairman, asked both parties to resubmit plans, which were due the Wednesday before Thanksgiving of last year. The parties complied. The Democratic maps, though, were little different from those that Colorado’s supreme court had rejected; one puzzled Republican commissioner deemed them “obviously deficient.” The following Monday, when the commission met to vote on a new plan, surprised Republican commissioners discovered two new Democrat-drawn maps, which neither they nor the media had any time to evaluate. It turned out that Carrera had quietly given the Democrats extra time to come up with the additional maps. Carrera voted with the Democrats, and the maps were adopted.

“The facts of the case were debated, but in the end the only thing that mattered was that, in a pair of 6 to 5 party-line votes with Chairman Mario Carrera voting with the Democrats, the two new Democratic resubmitted maps were accepted,” Robert Loevy, a retired political-science professor and a Republican commissioner, wrote later. The maps crammed ten current Republican state legislators into five new districts, where they would have to compete with one another. Loevy called it “one of the severest gerrymanders in state political history.” The independent-commission structure in Colorado, he concluded, was a “total failure.”

Whether partisan legislatures or nonpartisan commissions are running the show, a major reason that redistricting remains arduous is the role that race and ethnicity play in mapmaking. Back in 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act (VRA) to ensure that black voters had equal access to the ballot box, which had routinely been denied in the South. Congress intended the bill to end various practices, like literacy requirements for voter registration, used to disenfranchise blacks.

But over time, as the Supreme Court and the Department of Justice issued expansive rulings on the VRA, the law came to protect blacks not just from blocked access to the ballot box but also—and far more radically—from any dilution of their votes. The courts and the Department of Justice began to regard with suspicion any redistricting map that potentially reduced a minority group’s ability to elect one of its own. Indeed, plaintiffs have successfully used the VRA (in particular, Section 2, which guarantees minorities the same opportunity as the rest of the electorate to “elect representatives of their choice”) to argue that minorities’ political representation should be roughly proportional to their population.

The result is often a form of officially sanctioned gerrymandering. “We have involved the federal courts, and indeed the Nation, in the enterprise of systematically dividing the country into electoral districts along racial lines,” Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has written. After the 1990 census, for instance, North Carolina submitted to the Department of Justice a redistricting map with one congressional district in which blacks were a majority of voters. The department demanded a second black district, and to create it, the state had to join areas 160 miles apart, incorporating places dissimilar except for their large African-American populations. Since it sliced right through the middle of the state, the new district also reshaped the rest of North Carolina’s political map, with many districts needing to be redrawn. A challenge to the map made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in a 1993 decision essentially kicked the case back to a district court, but in language that called into question gerrymandering solely for racial purposes.

In subsequent cases, the Supreme Court has made a muddle out of the Voting Rights Act as it applies to redistricting. On the one hand, the court has observed that racial gerrymandering rests on the “offensive and demeaning assumption” that voters of the same race think alike and will prefer candidates who share their skin color. Yet the court has also, incoherently, continued to hold that minority voters’ ability to elect candidates of their own race is important, though how to determine the best way for a redistricting map to serve this end is “complex in practice.” In pursuing this line of jurisprudence, Thomas argues, the court has contributed to the “racial balkanization of the Nation.”

And so, when states with diverse populations draw election districts, they often place an overwhelming emphasis on race. Redistricting expert Tony Quinn points out that nine of the 14 members selected for California’s 2011 redistricting commission were minorities, even though whites make up 58 percent of the state’s population. Race played a big role in the mapmaking itself, Quinn adds: “Often the commission went to ridiculous extremes in its racial line drawing.” The commission’s two black members, for instance, refused to consider any plan for Los Angeles that reduced the number of congressional districts where a black candidate was likely to be elected below the current level of three, even though population decline means that blacks now constitute just 8 percent of the city’s total population, down from about 9.5 percent in 2000. This concern with race helped Democrats, Quinn says, since minority voters tend to support Democratic candidates.

In his account, Loevy detailed how Colorado’s redistricting commission, working under a court ruling that Hispanics deserved a state house of representatives district in the southern part of the state, created one of the oddest districts ever mapped. House District 62 spreads out broadly from east to west in southern Colorado, but then snakes upward along a narrow band of Interstate Highway 25, moving through sparsely populated land until it reaches the southeastern rim of Pueblo. Why the bizarre shape? There weren’t enough Hispanics in Colorado’s south to fulfill the judicial mandate, so the commission needed to extend the district up to a Hispanic neighborhood in Pueblo—in the central part of the state—to create a minority-majority “southern” district. “Despite being an obvious gerrymander, House District 62 generated no critics or detractors,” Loevy observed.

The perception that the courts require racial representation in redistricting is pervasive, even in cases when they don’t. Asian-Americans haven’t experienced the long-standing exclusions faced by American blacks; indeed, they wield disproportionate economic power today, with an average household income 15 percent higher than that of white families. Yet California’s redistricting commission used race in several cases, including Congresswoman Chu’s, to create districts ensuring the election of Asian-American candidates. At one point, though there was no judicial pressure to do so, the commission placed two Asian neighborhoods that were miles apart in San Diego into the same state senate district to help get an Asian candidate elected.

Congress renewed the Voting Rights Act in 2006, so its influence on redistricting is likely to remain substantial. One part of the act does face potential overthrow by the courts, however: Section 5, which requires nine states with a history of denying blacks the right to vote—plus dozens of counties in other states with similar past abuses—to “preclear” all changes in their voting laws, including redrawn districts, with the Department of Justice.

Officials in many of those jurisdictions have argued that evidence of racism is long in the past and that the onerous preclearance requirements should no longer apply. Georgia representative Lynn Westmoreland has noted, for instance, that “an academic study documents that black Georgians vote at higher rates than white Georgians” and that “black representation in statewide offices almost exactly parallels their proportion in the state’s population”—so why the continued federal oversight? When Congress, in renewing the act, refused to allow jurisdictions to exit Section 5, a number of them sued, claiming that it was unconstitutional for the federal government to preclear their election laws, absent any evidence that widespread racism still existed there.

Already, in a 2009 decision, the Supreme Court has let a small Texas district escape Section 5. Though the court avoided the larger issue of whether the preclearance program was unconstitutional, the justices suggested that the formula used to determine which districts it applies to may have become outdated. That ruling has prompted other districts to file their own lawsuits, seeking to have Section 5 declared unconstitutional, an outcome that some court observers think is increasingly probable. If so, it will be Justice Thomas who leads the way. As he wrote in a 2009 opinion, “The burden remains with Congress to prove that the extreme circumstances warranting Section 5’s enactment persist today.”

To understand the full implications of racial gerrymandering, consider a state that lacks it: Iowa, which is 91 percent white and where no county has more than a 20 percent minority population. The state consequently doesn’t have to worry about drawing districts for the sake of electing minority representatives. Not coincidentally, Iowa also has the country’s most nonpartisan, nonpolitical redistricting process; the National Conference of State Legislatures describes it as “unlike any other state” in this regard. In Iowa, a nonpartisan legislative staff draws maps for the state legislature without consulting political or election data or the addresses of current incumbents. The staff merely uses population data and standards laid out in Iowa law: districts must be compact, no county may be divided in creating one, and dividing communities should also be kept to a minimum. “The rationale and philosophy behind Iowa’s statutorily required redistricting process is that a blind system, from a partisan perspective, will most often result in an acceptable redistricting plan,” the state’s redistricting experts write.

The results are unusual by the standards of maps drawn elsewhere. Iowa’s four U.S. congressional districts are essentially rectangular, with some small extrusions to equalize their populations. The state legislature’s 50 senate districts and 100 house of representatives districts look like boxes piled on top of one another or arranged adjacently, with often regular borders and with house districts compactly placed within larger senate districts. Legislators in the politically divided state—Republicans currently control one house of the state legislature and the governor’s mansion, while Democrats control the other house—routinely approve the maps. This year, observers agree, Iowa’s redistricting favored Democrats in Washington by forcing two incumbent GOP congressmen to compete in a single new district. But the plan also gives Republicans a fair shot at controlling both houses of the state’s legislature.

Replicating what Iowa does may prove impractical because it is so unlike other states. But it’s still possible to refine redistricting, especially in states with nominally nonpartisan commissions. For one thing, states should require their commissions to approve maps by more than a simple majority, to avoid Colorado-like scenarios in which a single “nonpartisan” commissioner swings the redistricting in one party’s favor. Requiring a supermajority for approval is likelier to generate concessions from all parties. If commissioners refused to make concessions under such conditions, they would risk losing the mapmaking power altogether and handing it to the courts.

Commission members should also follow certain basic principles of mapmaking that states can write into their redistricting legislation. Foremost, commissioners should try to create districts that are compact and that don’t stretch or elongate boundaries in a way that bypasses whole populations to incorporate other targeted voters. Also, districts’ populations should vary by no more than 1 percent—partly because every citizen’s vote should carry equal weight, of course, but also because larger deviations give partisan interests more flexibility to craft districts incorporating special- interest groups. Mapmakers should respect established political boundaries, including county, city, and town lines, not breaking up these communities except in the rare cases when it might be necessary to ensure that districts have roughly equal populations. At the same time, states should eliminate from their redistricting laws any reference to “communities of interest,” a term often used to justify drawing electoral maps to satisfy ethnic, racial, and other special-interest groups, even when federal law doesn’t require it.

Critics of partisan gerrymandering describe it as a method by which politicians choose their own voters. But the problem persists even once those politicians have been removed from directly controlling the process—as the upcoming 2012 elections will show all too clearly.

*The Texas primary has now been scheduled for May 29 with an interim map while court challenges against the state’s maps continue.

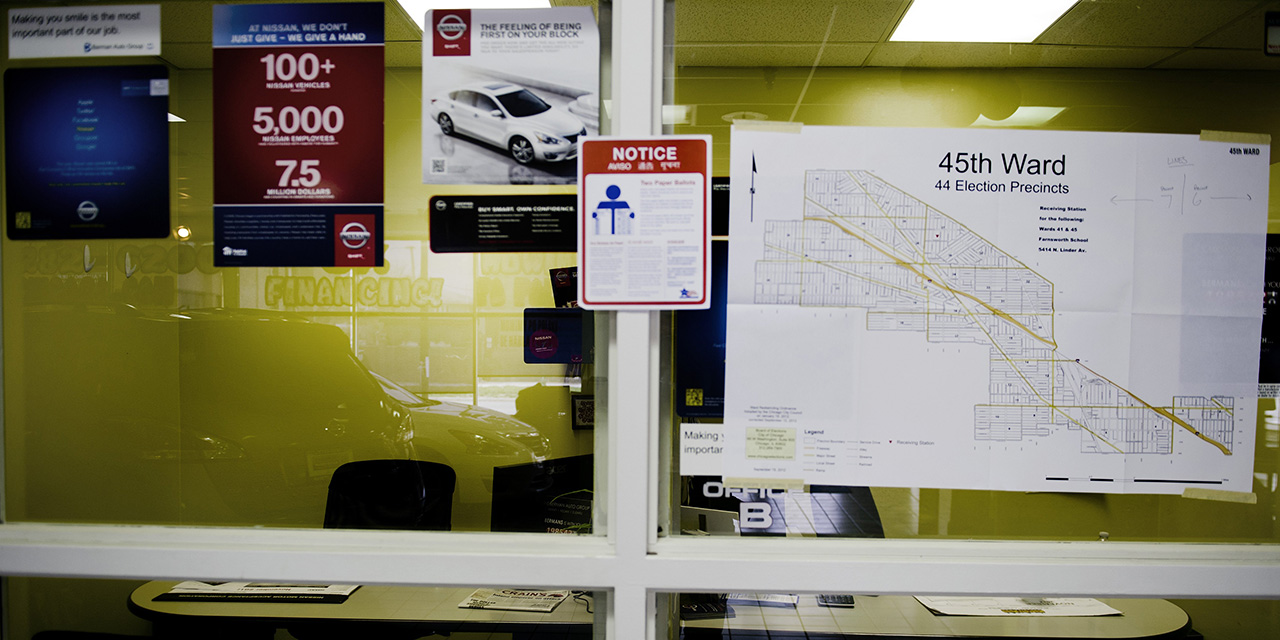

Photo: JIM WATSON/AFP via Getty Images