Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1918, by Mike Wallace (Oxford University Press, 1,196 pp., $45)

For years, whenever mentioning the historian Mike Wallace, one always had to add, “not the 60 Minutes Mike Wallace.” Around 1999, however, it may have been the 60 Minutes Wallace who felt at a disadvantage, for Mike Wallace, New York historian, had become improbably famous. For decades a well-known figure in academia, he became more broadly known as the Pulitzer Prize-winning coauthor (with Edwin G. Burrows) of the bestselling Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, and then as the principal talking head in Ric Burns’s monumental New York: A Documentary Film, in which his role resembled that of Shelby Foote in Ken Burns’s Civil War series. He stayed momentarily in the limelight, founding the Gotham Center for New York City History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and writing A New Deal for New York (2002), a plea for a 1930s-style rebuilding of the city that appeared at a time of uncertainty about the city’s future after the 9/11 attacks. And then, just as suddenly as he had leapt into public view, Wallace receded again. He was, we were told, at work on the sequel to Gotham, taking the story up to the present day.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Published in 1998, Gotham covered some 300 years of New York history and weighed in at 1,383 pages; Wallace’s new book, Greater Gotham, covers just 20 years—from 1898 to 1918—but takes up 1,196 pages. These bookend years are notable: the first is the year of the Consolidation of Greater New York, when America’s most populous and fourth-most populous cities (New York and Brooklyn) merged into a super-city, the supremacy of which no other U.S. city would ever contest (as Chicago had lately contested New York City’s status); the second marks the end of World War I, when New York emerged as the central city of a new world order.

New York’s history has been so eventful that any 20-year chunk of it would make for an interesting book. But the first two decades of the Consolidation offer particularly rich material, and Wallace covers as much of it as he can. In his introduction, he describes his approach: a series of views from above that move closer and closer to the ground, from a discussion of Wall Street–Washington relations (in which such figures as J.P. Morgan and Elihu Root loom large) to the merger mania that created the trusts (from petroleum to chewing gum) and conglomerates (U.S. Steel, the first billion-dollar corporation). In models of concise summary, he offers swift yet remarkably detailed histories of the city’s investment banks, commercial banks, trust companies, and insurance companies. Wallace is a superb writer: he has the experienced scholar’s sure sense of what to put in and what to leave out, and his prose has almost breathless forward motion, keeping the reader going page after page after page. He zooms in on different levels and aspects of the urban experience: from garbage collection to opera, from zoning (introduced in New York in 1916) to immigration (this is the era of the southern Italian and eastern European Jewish mass migrations). This was also the era of the building of New York’s greatest institutions—universities, museums, and libraries. In a section on the New York Public Library, Wallace quotes Lenin, who, after reading the 1911 annual report of the New York Public Library, wrote in Pravda of his awe at what New York had accomplished: “making these gigantic, boundless libraries available, not to a guild of scholars . . . but to the masses, to the crowd, to the mob! . . . Such is the way things are done in New York.”

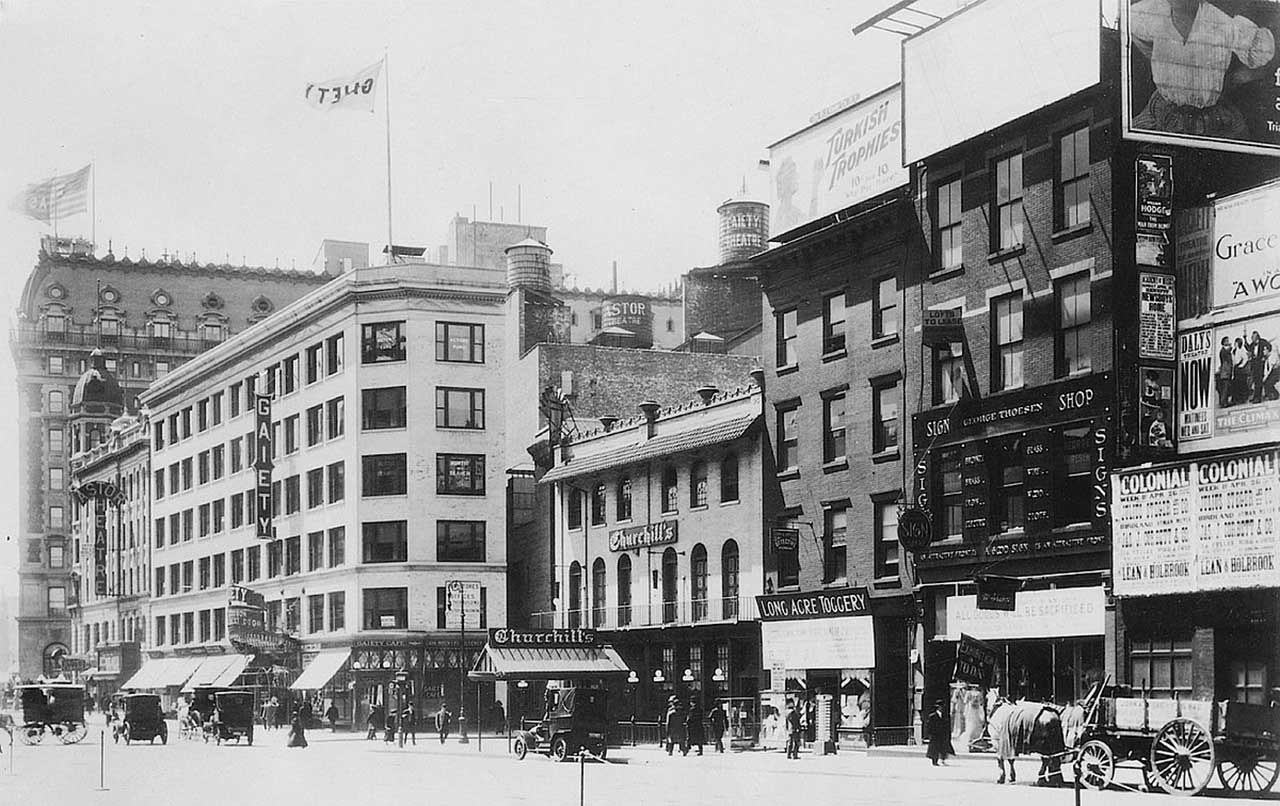

One gets a good sense of the book’s scope and approach by going to chapter 14, “Popular Cultures,” where we learn of the birth of nightlife, when for the first time unchaperoned young men and women attended public dances, first in rented halls, then in commercial dance palaces in Times Square and Coney Island, where “servants, stenographers, salesgirls, and seamstresses shed their shirtwaist-and-skirt regalia and donned gaudy eye-catching outfits that, like Bowery fashions of the past, copied and parodied elite styles.” In Turkey Trots and Bunny Hugs, dancers “mimicked animal movements or pressed their loins together in mock intercourse.” Alarmed reformers (those perennial killjoys of Gotham life) feared for the girls’ morals—and sexual exploitation by unscrupulous men. Before Rihanna and Miley, there was Irving Berlin’s “Everybody’s Doing It Now,” New York’s nightlife anthem of 1911. As for the elites, they couldn’t wait to join in on the fun. Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish hired black ragtime bands to play at her dance parties at Sherry’s. Society women attended afternoon tea dances at hotels where they danced—sometimes the tango—with immigrant men for hire, such as a recently arrived young Italian named Rudolph Valentino. African-American musicians provided the soundtrack of New York nightlife. Initially barred from union membership, black musicians became the city’s highest-paid, and soon broke down union barriers. The anarchic spirit of New York nightlife was harnessed and mainstreamed by such performer/entrepreneurs as Vernon and Irene Castle and deftly marketed by the formidable Elisabeth Marbury. The divine Irene pioneered bobbed hair and unconstraining clothing—no corsets, no heavy petticoats—and supplanted the Gibson Girl as the symbol of American glamour. She was also the prototype of the “flapper,” and Wallace helps us understand that much of what we associate with the flapper era and Prohibition lifestyles of the 1920s was already well in place in New York by 1918.

Wallace, whose father was a band leader, knows his music, too. He’s especially good on the career of Sophie Tucker, daughter of a Yiddish-speaking Orthodox immigrant family who, early on, was a blackface “coon shouter,” until her popularity enabled her to take control of her career. Refusing thereafter to appear in blackface, she artfully combined African-American and Jewish musical styles, hired and promoted black musicians, employed risqué material and double entendres, and wowed them at such nightclubs as Reisenweber’s at Columbus Circle. She was, writes Wallace, “at the vortex of a cultural whirlwind that was transforming the city’s gender, sexual, ethnic, and racial arrangements.” This chapter is a model of how urban history should be written. Reisenweber’s, Wallace dutifully points out, was at the southwest corner of Eighth Avenue and 58th Street; whenever he mentions a building, he tells us exactly where it stood (or stands). Historians hardly ever do this, yet the specificity is compelling, and it’s one of my favorite things about this book. (Another is that he refreshingly relegates those shopworn figures of this era, Stanford White and C.K.G. Billings, to footnotes.)

A student of Richard Hofstadter’s at Columbia in the 1960s and active in the student protests there in 1968, Wallace was a founder of the Radical History Forum in 1973 and of Radical History Review in 1975. He is very much a man of the political Left. He essentially views capitalism and social justice as at odds with each other. To the extent that immigrants in New York succeeded, he believes, it was not because they were buoyed by a vibrant economy but because they used their collective influence to effect social reforms (from New York’s neighborhood libraries to powerful labor unions) that, in time, would usher in New York workers’ golden age, which, Wallace notes elsewhere, was the middle of the 20th century. Expect to find, in Greater Gotham, a great deal about the labor movement and about such events as the Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire. These are, of course, major subjects, and Wallace does them justice; they are, as they may not be for all readers, linchpins of his worldview. Still, Greater Gotham’s overt leftism should not put off readers of different outlooks, because Wallace has such love for his subject and because his writing has such verve. Unlike most academics, he never appears merely to be going through the motions, and he never uses jargon that distances writer from reader. Breathtaking in scope and penetrating in detail, Greater Gotham revels in New York’s sheer force, energy, and creativity.

Photo: Wurts Bros. / New York Public Library