As the American economy struggles to recover from the Great Recession, it may have no better medicine than Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution. Unanimously approved by the Constitutional Convention in 1787, the “patent clause” authorized the new government to “promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” This conception of intellectual-property rights was strongly supported by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, who believed that ideas would be the engine of American wealth creation and that legal protection for them was therefore essential. After all, unlike the British, Americans had little accumulated capital; their most important resource would be their entrepreneurial spirit. Congress soon passed the Patent Act of 1790, which created a patent office, and Jefferson himself served as the first commissioner, a position he held while also being secretary of state.

Part of Madison’s and Jefferson’s plan to seed innovation was that access to patents would be open and democratic. In Britain, patents tended to go not to innovators but to well-heeled supplicants of the Crown, who got undeserved monopolies. In America, by contrast, people would apply for patents by paying a fee, and that fee would be low enough—$3.70 during the Founding era—to allow most serious inventors to file. The fees were nevertheless sufficient to make the patent office the only federal body that cost the taxpayer nothing, a distinction that it still holds.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The Founders’ vision soon proved its worth. By 1820 or so, the United States was issuing more patents yearly than the United Kingdom, and by around 1830, America’s per-capita income had vaulted ahead of Britain’s (and France’s). America continues to be the most innovative and wealthy nation on earth. But its innovative edge is in danger. One problem is the patent office itself, which is failing to keep up with applications for patents. Another is China, which cavalierly violates patents and copyrights, costing the U.S. economy hundreds of thousands of jobs.

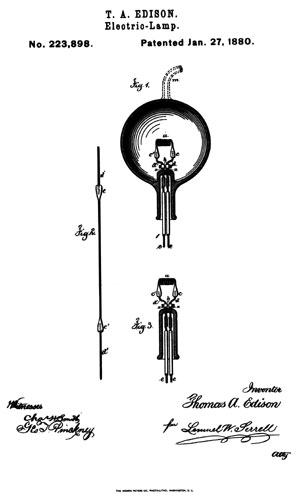

In his enlightening book Great Again, self-described “serial entrepreneur” Henry Nothhaft, the former CEO of San Jose–based miniaturization innovator Tessera, makes a powerful case for improving the patent process. The typical high-tech entrepreneur, Nothhaft points out, is a lonely inventor, comparable with nineteenth-century figures like Thomas Edison and Robert Fulton. Think of tech icons Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and the late Steve Jobs, all of whom started from the ground up as unknowns. Without patents, such innovators will have a tough time bringing in financing, whether through bank loans or, better, venture capital. According to one recent survey, about three-quarters of start-up executives say that patents are crucial to securing funding. And the need for patent protection is most acute in the most economically promising sectors, including information technology and biotechnology, where competition is particularly fierce.

When an inventor does secure a patent, good things happen economically. Research shows that the average patent yields five new jobs. According to Berkeley’s Patent Survey, of the 70 million private-sector jobs created in the U.S. since 1970, two-thirds were created by small start-up firms, which rely heavily on patents to make their mark. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is thus “the biggest job creator you never heard of,” Nothhaft says.

So the fact that the USPTO no longer functions properly represents a significant loss to the American economy. Each year, the office, located in Alexandria, Virginia, delivers about 185,000 “utility patents” (distinct from “design patents,” which cover the way products look) for U.S. firms, a number that has remained roughly the same for the last ten years. But the office is getting bogged down. It has accumulated a vast backlog of unexamined applications—currently 700,000, on top of another 500,000 that have passed only the earliest stage of the lengthy approval process. An inventor now needs to wait almost three years to obtain a patent, up from 18 months a decade ago. That’s a lifetime in fast-moving high-tech fields. From an economic standpoint, this backlog represents hundreds of thousands of uncreated jobs, says USPTO director David Kappos, who left his high-paying job at IBM to try to break the patent logjam.

There are several reasons for the congestion. Nothhaft assigns part of the blame to bureaucratic problems at the patent office, including turnover of experienced staff, poor recruitment efforts, and obsolescent computer software. Bigger reasons are the number of patent applications—which has been steadily rising, from about 300,000 in 2000 to about 480,000 last year—and the increasing complexity of the typical request, a reflection of proliferating new technologies. More complicated applications, naturally, take more time to process.

Why not just increase the application fees and use the money to hire more patent and trademark examiners? Any fee increase requires congressional approval, and lawmakers have been hesitant to enact one, fearing that it could discourage the little guy with a great idea from seeking a patent. (At the moment, individual inventors pay $3,000, on average—but most of them use lawyers to file, and once you add the legal fees, Nothhaft estimates, they’re spending about $34,000 apiece.) Congress, it’s worth noting, also siphons off some of the patent office’s fees for other purposes.

But help is on the way. A promising new law, approved by the Senate and signed by President Obama in September, will raise application fees for larger companies, which file about half of all applications, while offering a new discount for individual patent seekers. It will also dedicate 100 percent of the fees to the patent office itself. These reforms will allow the USPTO to hire new permanent staff and speed up rulings.

The law also includes a controversial shift in the USPTO’s procedure. Under the old system, the examiners spent time and energy making sure that the innovation submitted for a patent hadn’t been discovered by an earlier inventor. The new system, which all European countries use, will instead simply award the patent to the “first to file.” Kappos, who supports the change, says plausibly that it will simplify the examiners’ work “enough to reduce the backlog.” It will not, however, alter what Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts, writing for the majority in the recent case Stanford v. Roche, called “the general rule that rights in an invention belong to the inventor”: someone who claimed to have originally invented a product could still sue for his intellectual property, even after the patent had been awarded to the first filer.

Nothhaft, along with many small-business groups, opposes the first-to-file approach, however, saying that it could dampen innovation. “Under first-to-file, large companies will file for an unlimited number of applications and drown the lonely individual inventor less equipped to file,” he warns. “The next Thomas Edison may well never get a patent.” Kappos responds that all new patent requests will be publicly available, so individual inventors will easily be able to discover when big corporate research-and-development departments are trying to corner a potential market by filing applications for things that they haven’t actually invented.

With the support of former federal circuit court judge Paul Michel, an expert in patent law, Nothhaft has proposed a one-time “surge” of $1 billion in funding for the USPTO. It’s a good idea. The money would allow the office to upgrade its computers and hire temporary examiners to work through the patent-application backlog, which would take about three years. Michel and Nothhaft note that such a surge would probably yield about 225,000 new patents for small businesses and generate between 675,000 and 2.25 million jobs. “Assuming a mid-range figure of 1.5 million,” they wrote in a New York Times op-ed, “the price would be roughly $660 per job—and that would be 525 times more cost effective than the 2.5 million jobs created by the government’s $787 billion stimulus plan.” (That’s if you believe that the stimulus package did create all those jobs.)

To keep its innovation edge, the United States must also prevent Asia’s emerging economies—China’s, above all—from violating American companies’ intellectual-property rights. Chinese competitors routinely crank out knockoffs of American products, ranging from cheap, obviously inferior, imitations to high-quality counterfeits. The results include reduced market opportunities and profits for U.S. firms, as well as damaged brand reputations.

Much has been written about China’s infringements upon American intellectual property, but until the U.S. International Trade Commission, an independent federal agency, issued a report this past June, their impact on the American economy had never been measured. Now we know: the impact is massive. Drawing on statistical analysis, case studies, and questionnaires, the report estimates that in 2008 alone, American firms lost $48 billion because of Chinese infringement. Copyright infringement of films and other entertainment products is the most widespread problem, thanks to the low cost of digital replication and the convenience of the Internet as a medium of exchange, but violations of intellectual property occur in everything from chemical manufacturing to information technology. Were the Chinese to respect intellectual-property rights the way the United States does, the report found, American firms would boost employment in their U.S. operations by as much as 5 percent, adding more than 900,000 new jobs. Improved intellectual-property protections would also increase American exports and affiliate sales to China by an estimated $107 billion, creating another 1 million jobs in the U.S.

China seems uninterested in respecting intellectual-property rights, though. Consider its evolving “indigenous innovation” policies, which prevent various foreign companies from competing with Chinese ones.

The International Trade Commission report offers no policy guidance on how to improve things. So far, the U.S. government has done little more than convey mild complaints to Beijing. A trade boycott would be unwise, since American firms still benefit from access to China’s domestic market, just as American consumers benefit from inexpensive Chinese imports. But whenever U.S. officials can prove that Chinese firms have infringed upon American competitors’ intellectual-property rights, they should no longer tolerate the Chinese authorities’ lies. Targeted retaliation could be an effective U.S. response—banning the import of Chinese goods made with stolen intellectual property, say.

Such a stance would not be “China-bashing” or mark the onset of a trade war. It would recall a similar situation, half a century ago, when emerging Japanese firms showed little respect for American intellectual property. After the U.S. threatened retaliation, the Japanese changed their ways and eventually came to understand that protecting intellectual property was the best way to improve the quality of their own products. Following the same learning curve, China should acknowledge that strong intellectual-property rights would help Chinese firms create and promote their own brands in the future, opening up far greater sources of profit than imitation does. Only when China grasps this point will a Chinese Edison emerge.

Innovation is the only way to achieve sustained growth and higher employment in America, and innovation depends on keeping intellectual-property rights strong. At the moment, neither major party is championing that approach as a way to boost job growth—a strange omission, when you consider how much cheaper, less artificial, and more effective it would be than, for example, the Obama administration’s Keynesian tactics. Only one Republican presidential candidate has addressed the issue: Mitt Romney, who has proposed a free-trade pact among countries that respect intellectual-property rights. But by making the patent office more efficient at home and by improving the protection of intellectual property abroad, the American government could form the conditions for entrepreneurs to create perhaps 5 million new jobs in just a few years. Unshackling their creativity would truly be a liberating economic policy.

Top Photo: Melpomenem/iStock