It’s been a rough recovery for American labor. In the aftermath of the 2007 financial meltdown and the deep recession that followed it, unions have bled more than 1.3 million members. Sharp declines in construction, manufacturing, and transportation jobs have battered private labor; tax shortfalls and high costs have led state and local governments to pare budgets, and hence public-union jobs. Meantime, unions face growing public resentment. Four states in recent years have adopted right-to-work policies, which let workers opt out of joining unions. Polls show that the public is increasingly questioning the efforts of labor groups and the economic toll they impose. Government unions may have dodged a bullet in late March, when an evenly divided Supreme Court refused to overturn state laws that allow obligatory worker fees, but unions have recently lost other key court cases, undermining their ability to organize.

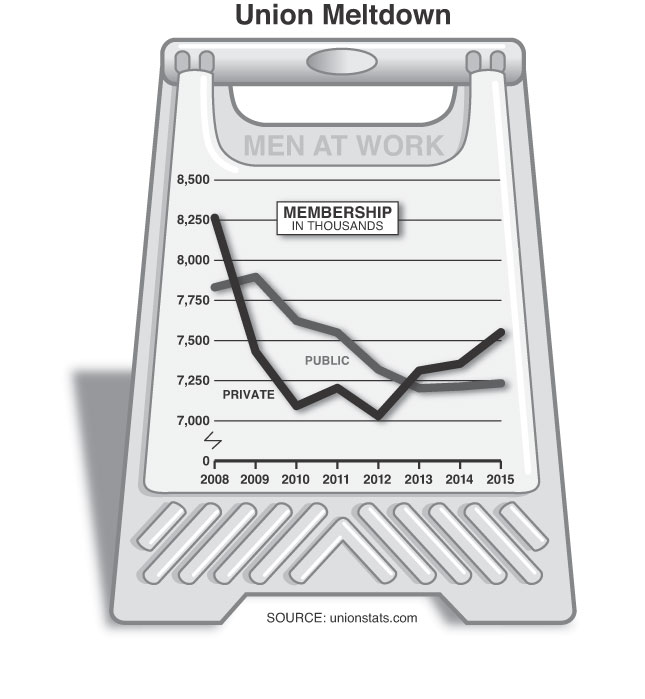

The Great Recession and the underwhelming Obama recovery have, in other words, reshaped the map of labor in the United States. Private unions began to rally somewhat in 2012 but thus far have regained only 42 percent of the members they lost. A disproportionate share of that rebound, moreover, has occurred in right-to-work states—not because these states are welcoming labor environments but because they’ve done better economically than union-friendly states. Public unions have yet to boost their rolls, six years after the recession ended. It was commonly observed, after 2009, that government unions had grown larger in membership than private ones—but this advantage proved short-lived. Three years ago, private unions regained their old lead.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Unions typically lose members in recessions. But years into an economic recovery, the striking decline in government-union membership and the limited recovery of private unions bode poorly for the labor movement. And with America perhaps facing another economic slowdown, things could soon get worse for unions.

America lost about 8.7 million private-sector jobs by the nadir of the economic downturn that began in late 2007 and continued until mid-2009. Private-sector union membership began dropping in late 2007, too, but it kept on falling for another two years after the recession ended. By the time membership started rising again, in 2012, private unions had shed 15 percent of their membership, or 1.2 million people. Since then, though the nation has regained all the jobs lost in the recession and added 5 million more, private labor unions remain 700,000 members short of their 2008 enrollment, according to unionstats.com.

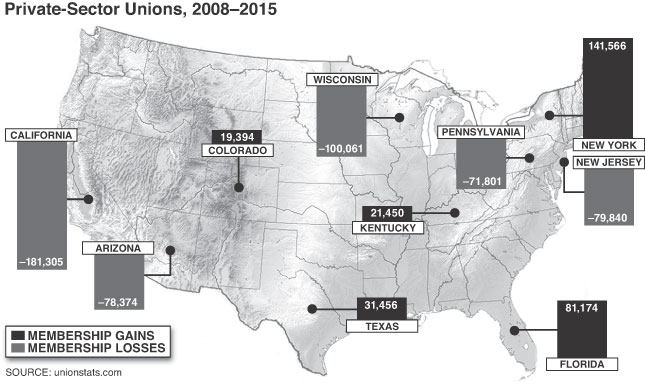

The unions’ most significant shrinkage has come in strong labor states. Of the 28 states at the start of the recession deemed union-friendly—that is, they had laws that compelled workers in unionized businesses to pay dues or fees to the union—all but six have fewer private-sector labor jobs today than they did in 2008. California has led the negative trend, with a staggering 181,305-member decline in private unions as of the end of 2015. New Jersey’s private-union rolls have fallen 79,840, Pennsylvania’s have slumped 71,801, and Illinois’s are down 69,614. The massive losses in these states more than offset labor’s one bright spot: 141,000 new union jobs in New York. In total, the compulsory-unionization states have accounted for approximately 675,000 of lost private-sector union jobs. True, three of these states have recently turned right-to-work, ending mandatory union dues, but two—Indiana and Michigan—sustained all their private-union losses while labor-friendly laws remained in place. Only in Wisconsin did union losses pile up after right-to-work went into effect, which happened last year. Private-unionization rates in pro-labor states plummeted. In Missouri, for example, unionization has fallen from 9.3 percent of private workers to 6.6 percent since 2008, while in California it dropped from 10.7 percent to 8.7 percent.

States with laws less friendly to unions, ironically, have been better for union jobs. Thirteen of the 22 states that were right-to-work in 2008 have more private-union jobs today. The biggest gainers include Florida (up 81,174), Texas (31,456), Virginia (16,313), and Louisiana (13,070). Most of these states have low levels of union penetration, however, and the gains have altered that fact only slightly. In Texas, just 2.5 percent of private-sector workers are unionized, the same level as in 2008, all the new jobs notwithstanding. Nebraska, Mississippi, and Georgia saw their unionization rates climb just 0.03 percentage points or less since 2008, despite union membership increases in each state; labor groups still enroll less than 5 percent of private workers in the three states. The unionization rate in Florida did rise by a full percentage point, but even with that rise, only 3.3 percent of the state’s private workforce belongs to unions, well below the national average of 6.7 percent.

Some of the recent rebound in private-union employment in right-to-work states owes to job growth. States that began 2008 with right-to-work laws have 41 percent of America’s population but have generated 60 percent of the nation’s new private-sector employment above the prerecession employment peak. And right-to-work states have added more blue-collar work, while the jobs being added in union-friendly states have largely been in industries not heavily unionized, like high technology in California. Since 2010, when manufacturing job losses bottomed out, the sector has regained 821,000 of the 2.3 million jobs lost during the downturn, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics; nearly seven in ten of those positions have been in right-to-work states, including Florida, Georgia, and Texas. One consequence is that manufacturing unions in these states have rebuilt their memberships more successfully than their counterparts in compulsory-unionization states.

In the face of this evidence, labor unions have nonetheless blamed antiunion forces for their misfortune. “We recognize . . . that right-wing billionaires’ extremist policies, a rapacious Wall Street and insufficient advocacy from political leaders thwarted further progress,” AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka said in early 2015 about the slow recovery of union rolls. The union’s membership, which had peaked at 13.7 million in 2005, was 12.5 million at the end of last year.

To speak of any recovery of private-union membership is somewhat misleading, since nongovernment labor positions created over the last few years are mostly in industries that didn’t lose employment during the recession—indeed, in industries not traditionally associated with labor. Health care, professional and technical services, and real-estate leasing and services have all seen expansion in unionized jobs and, with the exception of health care, an increase in the percentage of workers unionized, too, though from single-digit levels. These industries typically share two characteristics that help unions. First, they involve service work that isn’t easily outsourced overseas. Second, in many instances, the work is connected to government, either through direct funding or through heavy regulation, which makes employers more likely to cooperate with unionization efforts, so as to build lobbying alliances for favorable government treatment.

Organizing campaigns for health-care workers in California illustrate how this process works. In 2003, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) launched a drive to unionize private nursing homes, many of which had patients with bills that state Medicaid programs were paying. The union made a pact with the owners of 42 nursing homes, telling them that it would push the state legislature for more funding if the owners didn’t try to block their unionization drive. The SEIU won thousands of new members, and the alliance subsequently gained $2 billion in extra Medicaid reimbursements for nursing homes over a two-year period.

Health-care unions have also turned to friendly politicians to help boost enrollment. In several states, Democratic governors have signed executive orders designating government-paid, home health-care workers as state workers, not independent contractors, as they’d previously been categorized. This allows unions to organize those workers into bargaining units, which isn’t possible with independent contractors. In Illinois, for example, Governors Rod Blagojevich and Pat Quinn enacted a series of such orders, resulting in the local SEIU unit signing up roughly 24,000 home health-care-worker members. The organizing drive and election proved controversial, however; many of the workers later said that they knew nothing about these efforts. Home health care has been among the fastest-growing areas of unionization, with 111,000 workers now in unions around the country—a 44 percent increase since 2008.

But labor’s new strategy may be only so effective. In June 2014, the Supreme Court overturned the Illinois directives after several workers sued the state, arguing that they weren’t really state employees—because they were hired and fired by those they worked for, not by Illinois. Since the Court’s decision, the Washington Times has reported, at least 8,000 dues-paying Illinois home health-care workers have left the union.

“Unions that represent grocery stores have lost 103,000 workers, a decline of 20 percent, since 2008.”

Other major organizing campaigns have also faltered in the post-2008 recovery. Over the last several years, unions have targeted fast-food workers with a highly visible “Fast Food Forward” drive, featuring rallies and sporadic strikes. The campaign’s impact has been nominal, at best. Though union rolls in restaurants rose by 13 percent, or 15,000 members, since 2008, that’s a small chunk of the more than 600,000 new jobs generated by fast-food and other limited-service restaurants over that period. Fast food’s unionization rate, meantime, remains a mere 1.6 percent. So far, the campaign’s failure mirrors unions’ other recent flubs—most notably, the ten-year-plus push to organize Wal-Mart and other discount stores, which has yielded few victories.

Indeed, retailing unions, which 30 years ago claimed some 1.25 million organized workers, have yet to regain the jobs lost from the latest downturn. Unions now count only slightly more than 750,000 retail members. More worrying still for labor, retailing’s most unionized sector—supermarkets and grocery stores—continues to shed members rapidly. Unions that represent grocery stores have lost 103,000 workers, a decline of 20 percent, since 2008; the unionization rate shrank to 15.5 percent from 20.6 percent, as the spread of nonunionized food stores—from high-end Whole Foods, which has vigorously resisted organizing efforts, to Wal-Mart super-grocery centers—has eaten into the business of unionized chains.

Trumka is right about one thing: unions haven’t won many friends in recent years. Since 2012, four states—Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and, most recently, West Virginia—have adopted right-to-work laws. The surge began when Indiana governor Mitch Daniels, in the last year of his second term, responded to pressure from members of the Republican-controlled state legislature to sign a right-to-work bill. Daniels had shown little interest in passing such a law during most of his tenure, but he has admitted that it sparked renewed business interest in the state: “I may have underestimated the impact,” Daniels said. “We have had a flood of calls and inquiries, starting literally the day I signed the bill.” Michigan quickly followed suit, and then Wisconsin in 2015. In early 2016, West Virginia’s Republican-controlled legislature passed a right-to-work law over Governor Earl Ray Tomblin’s veto.

In general, employees’ freedom in right-to-work states to opt out of union membership restrains labor’s growth; right-to-work states have, on average, only about a 4 percent rate of unionization in the private sector, compared with 9 percent in compulsory-unionization states. The rapid addition of new right-to-work states since 2012—it had taken a half-century for the previous group of four states (Wyoming, Louisiana, Idaho, and Oklahoma) to adopt the policy—reflects changing attitudes toward unions. A 2014 Gallup poll found that 53 percent of Americans approved of unions—down from about 70 percent in the late 1960s. More significantly, 71 percent also supported giving workers a choice of whether to join a union, something that unions themselves fight against vigorously. “Americans . . . are clearly less supportive of labor unions, and somewhat more supportive of right-to-work laws, than in the past,” Gallup’s Jeffrey Jones said.

Union members might also begin wondering whether labor leaders are their own worst enemies. One of the movement’s biggest campaigns these days, for instance, is to get states and the federal government to hike up the minimum wage. Successful efforts in 12 states in 2014 and 2015 are raising rates—in some cases, dramatically. California and New York enacted laws that will eventually move their minimum wages to $15 an hour. Unions argue that a higher minimum wage helps lift workers out of poverty, but research shows that it also destroys jobs or drives them to less expensive environments. Writing recently in the Wall Street Journal, the chief executive officer of CKE Restaurants, Andy Puzder, described growing automation in his business and attributed it to the rising price of employing workers: “Dramatic increases in labor costs have a significant effect on the restaurant industry, where profit margins are pennies on the dollar and labor makes up about a third of total expenses,” he explained. Shortly after California governor Jerry Brown signed the state’s latest minimum-wage boost, Los Angeles–based American Apparel said that it might relocate 500 jobs—not overseas but to another state. Apparel manufacturing has lost 71,000 jobs in California in the last 25 years, a 60 percent decline, and American Apparel was one of the few major employers still in the state.

And from the looks of things, union jobs are particularly at risk. The 28 states that since 2008 have raised their minimum wages faster than the federal wage floor increased have borne the vast majority of private-union job losses—560,000 in total. That’s more than three times the losses in states where the minimum wage rose merely at the federal rate, a boost of 70 cents per hour over that time period.

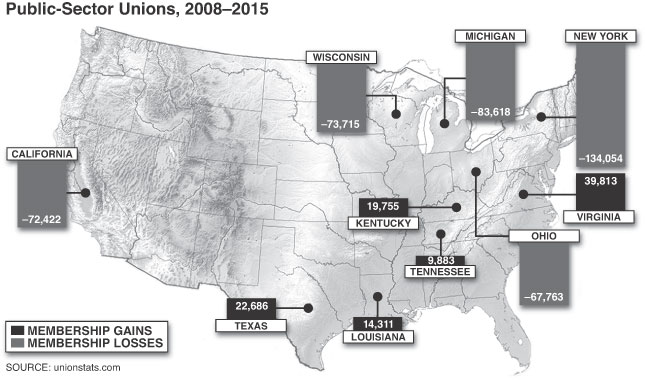

As tough as the post-2008 period has been for private unions, their public-sector counterparts have had it even worse. State and local budgets have remained under intense pressure since the recession, as tax revenues have grown only haltingly and government costs—especially employee costs—have risen fast, producing a near-continuous squeeze on finances. In response, state and local governments have slashed about 700,000 jobs. Unionized government workers bore the brunt of cuts, with membership down about 660,000 workers, or 8 percent, since 2008.

Most of the lost jobs were municipal—that is, held by workers employed by towns, counties, cities, and school districts. That’s not surprising: local government budgets are largely made up of employee costs. The typical school district budget, for instance, is composed of 80 percent personnel costs, leaving administrators few alternatives but to lay off workers during major fiscal nosedives. As in the private sector, labor-friendly states have taken some of the biggest losses in government-union rolls. Just eight states, led by New York—with the highest rate of public unionization in the country—and including California, Ohio, Washington, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Illinois have accounted for nearly 427,000 lost government-union jobs, 66 percent of the total national reduction in the public sector. Just six of the 24 compulsory-unionization states have more government-union jobs today than in 2008.

Public-sector unions have also taken significant hits in two states that have adopted right-to-work rules during the last five years—Wisconsin and Michigan. Wisconsin passed a law in 2011 eliminating mandatory fees for government workers who don’t want to belong to a union and narrowing collective bargaining for many government workers. Unions have subsequently lost nearly 74,000 members in Wisconsin, where previously nearly half of all government workers were unionized. Michigan saw a drop of about 25,000 government-union jobs after the state adopted a right-to-work law in 2012.

Some of the nation’s most politically muscular labor organizations haven’t escaped these trends. The National Education Association, America’s largest labor group, has seen its membership fall by 282,000 since its 2009 high, according to the Department of Labor. Education Intelligence Agency (EIA), a blog that closely follows teachers’ unions, has counted 22 state NEA affiliates with fewer members today than they had 20 years ago. Meanwhile, 17 state teachers’-union locals operated in the red during the 2014 school year, the latest for which data are available, EIA reports. The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Workers, which represents the largest number of noneducation public workers, has lost 196,000 members. Neither NEA nor AFSCME has avoided shrinking membership in any of the last five years.

The outlook going forward isn’t much more promising for government unions—especially because the country may be nearing another economic downturn after more than six years of expansion. If so, local governments are in the weakest position in decades to withstand such a storm. State and local collections of property, income, and sales taxes peaked before the downturn at $1.22 trillion, before falling off a cliff and then recovering only slowly. By the end of 2015, taxes brought in $1.33 trillion in revenue, which represents an average annual growth rate of just 1.25 percent since 2008. The skyrocketing price of benefits negotiated by workers has made it hard to reduce costs, even when governments have reduced their workforce. Rising pension bills are a key reason. Since the financial crisis, annual contributions by state and local governments, including schools, into underfunded pension systems have risen by about $47.8 billion, or 64 percent, to $121 billion, even as government payrolls have shrunk. And paying down retirement-related debts in some states will require years of higher contributions. Union-friendly states will face the greatest financial squeeze. A new study on government pension debt by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research shows that nine of the ten states with the greatest unfunded pension liabilities are union-friendly environments, including Illinois, California, and New Jersey. At the same time, state tax collections have started to slow again, apparently because of a weakening economy. The Rockefeller Institute for Government predicts that tax revenues will likely deteriorate throughout 2016 and 2017.

Further, with budgets pressured, public opinion has turned against many government unions. Recent polling by Harvard’s Program on Education Policy and Governance, for instance, found that only 30 percent of those surveyed say that teachers’ unions have a positive impact on schools, while 39 percent view their influence as a negative. Some opponents have taken the case against unions into the courts. In 2012, the parents of nine California public schoolchildren filed a case arguing that the state’s teacher-tenure laws, which grant many teachers virtually permanent employment, regardless of their abilities, violated children’s right to receive an adequate education. A California superior court ruled for the plaintiffs in 2014, but an appeals court overturned that verdict. Now the state’s supreme court must weigh in. A ruling against the union threatens to upend the entire union-backed regime of teacher job security in the state, and could spark copycat suits elsewhere.

Government unions narrowly escaped a potentially far more damaging outcome in March, when the Supreme Court failed to overturn a nearly 40-year-old ruling that lets unions collect mandatory fees from workers. In Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, ten teachers objecting to forced fees sued the California teachers’ union. All indications during Supreme Court oral arguments in January suggested that a majority of justices were sympathetic to the plaintiffs. But the untimely February death of originalist justice Antonin Scalia resulted in a 4-4 split in Friedrichs, protecting the fees—at least for now. The lawyers for the Friedrichs plaintiffs have refiled the case, however, and other workers unwillingly paying fees may sue on their own. “We can’t leave this issue for another time,” says Terry Pell, president of the Center for Individual Rights, the public-interest law firm that brought the case. “The Court has already agreed to decide this case and it should hold the case until it can issue a definitive decision.”

If Scalia’s eventual replacement (whoever that may be) sees the issue in the same way as the Court’s conservative judges, these kinds of fees may yet disappear. The sudden fleeing of workers from labor’s rolls in places like Wisconsin and Michigan after they ended compulsory unionization suggests what might then be in store for public unions. Such a scenario could make organized labor’s recent struggles seem mild by comparison.

Top Photo: Jim West/The Image Works