In 1924, American art was experiencing a postwar renaissance. Georgia O’Keeffe was leading a group of promising painters; Daniel Chester French had recently finished his sculpture of Abraham Lincoln for the new memorial in Washington; Alfred Stieglitz was developing a new kind of photography; Frank Lloyd Wright’s reputation was soaring. So readers were shocked by Gilbert Seldes’s declaration in his book The Seven Lively Arts that “the daily comic strip of George Herriman is, to me, the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America to-day.”

Seldes wasn’t being perverse, and he wasn’t alone in his enthusiasm for Herriman’s Krazy Kat. A ballet inspired by the strip had been performed at Town Hall in midtown Manhattan; its composer described the title character as “Don Quixote and Parsifal rolled into one.” The great jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke would soon record a song called “Krazy Kat.” Other Herriman aficionados included Pablo Picasso, Charlie Chaplin, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and H. L. Mencken, who clipped the Kat’s daily adventures and glued them to the wallpaper of his living room. While Woodrow Wilson occupied the White House, he never missed an episode.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Yet fame eluded Herriman, and vice versa. Over the years, Chester Gould gained renown as the creator of Dick Tracy, and Harold Gray as the father of Little Orphan Annie. Readers learned that Chic Young drew Blondie and that Al Capp was responsible for Li’l Abner. But hardly anyone could name the man behind Krazy Kat—and that was just fine with him.

As biographer Michael Tisserand notes, Herriman’s light-skinned Creole parents ran a tailor shop in New Orleans, then in its harshest Jim Crow phase. In 1890, when their boy was ten, the family moved to Los Angeles, opened a bakery, and “opted to passe blanc, or ‘pass for white.’ ” Decades later, when Krazy Kat ran in tabloids across the country, “those same papers on their front pages were reporting scandals when it was found that some prominent person was revealed to have black ancestors. Herriman must have known that he was one headline from that kind of scandal his whole life.”

Though well educated in Catholic schools, George showed no interest in college. Teachers had praised his ability to render desert scenery, which he had observed during family trips to Arizona, still a territory at the time. Encouraged, he dropped out of high school to seek an artistic career. By 1898, the teenager was doing spot illustrations for the Los Angeles Examiner. Comics were extremely popular at the turn of the century, and editors urged George to produce his own daily strip, but none of his many attempts caught on with readers. Undaunted, he headed to New York, the city of journalistic opportunity, where more than 20 daily newspapers and dozens of magazines were published.

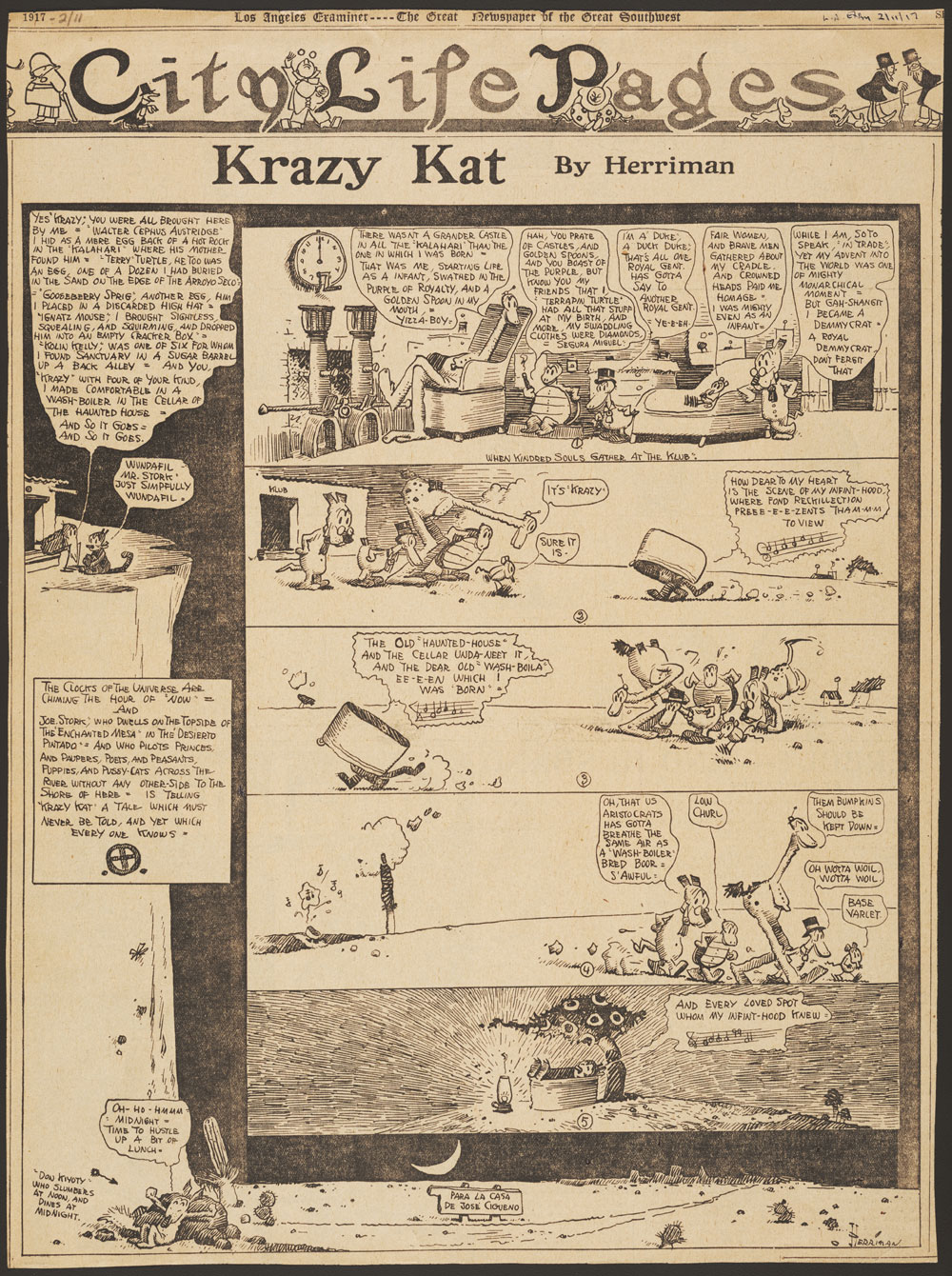

Relocated and newly married, Herriman tried a series of short-lived strips for various periodicals. One of these was The Dingbat Family, produced for William Randolph Hearst’s King Features syndicate. It featured a series of two-level sketches, anticipating Upstairs, Downstairs by 60 years. On the main floor, humans went their farcical ways; down below, a cat named Krazy and a mouse called Ignatz performed slapstick routines. In 1913, the animals were spun off into a strip of their own, and that’s when things got interesting.

Krazy Kat was based on a triangle that would have confounded Euclid. Ignatz detests Krazy and frequently beans the feline with bricks. These attacks only arouse the amorous feelings of Krazy, who’s mad about Ignatz. The third member of the trio, Offissa Pupp, has a crush on the Kat and detests the Mouse. He does what he can to protect his sweetheart, though the puppy love goes unrequited. A supporting cast of anthropomorphic fauna includes Kolin Kelly, a brick-making dog; Joe Stork, who delivers babies for a living; Bum Bill Bee, a flying insect; and Don Kiyote, a high-toned Mexican jackal.

Given the one-joke format and the surfeit of puns, Krazy Kat should have had the life span of a mayfly. But Herriman had three extraordinary assets: a mastery of landscape, an acute ear for dialect, and an antic sense of farce. Krazy Kat takes place in Coconino County, a real locale in Arizona and a surreal place in the artist’s mind. Jutting rocks, tall cacti, hard volcanic soil, and brilliant colors (on Sundays) suggested the Painted Desert and Monument Valley. They also suggested the stark, threatening backdrop of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land.

Herriman pared each panel to its essentials. Those panels could be circular, square, or oblong; within them, props shifted from scene to scene, as if Herriman were ad-libbing vaudeville sketches. If a brick turned out to be extraneous in one drawing, Ignatz would make a slit in the background and get rid of it. At times, the principals read a newspaper showing the very strip in which they were appearing. Mid-dialogue, a sequence would go from pitch-black to high noon. The Kat occasionally changed from black to white, as befitted his creator, who wrote and drew in his own cryptic code.

Krazy would even shift sex—sometimes referred to as “her,” sometimes as “him.” A bewildered fan asked whether the strip’s lead character was male or female. Recalled Herriman: “I fooled around with it once; began to think the Kat is a girl—even drew up some with her being pregnant. It wasn’t the Kat any longer, too much concerned with her own problems—like a soap opera. Know what I mean? Then I realized Krazy was something like a sprite, an elf. They have no sex. So Kat can’t be a ‘he’ or a ‘she.’ The Kat’s a sprite—a pixie—free to butt into anything.”

And butt he/she did, anatomizing other characters’ statements. When one of them says that the bird is on the wing, the Kat disagrees: actually, the wing is on the bird. Krazy encounters some birdseed and scratches his head; he always thought birds came from eggs. When Ignatz observes that Don Kiyote is “still running,” his perennial target responds: “Wrong. He is either still or either running, but not both still and both running.”

Herriman used invented spelling to reproduce the accents and patois that he’d heard in New Orleans, Los Angeles, and New York. Yiddish: “Ooy, such an ecsent, just jabba, jabba, jabba. Don’t min a thing by me.” German: “Iss diss der willitch of Koo Koo Ninni oder vot?” Italian: “Spikk plaina, plizz.” And Creole as well: in prehistoric times, we learn, there were “big kanary birds. What was called ‘peter-dectils.’ But alas, all they is left of them nowadays is bones.” Verbal communication itself became a frequent subject of discussion in the strip:

Krazy. Why is lenguage, Ignatz?

Ignatz. Language is that we may understand one another.

Krazy. Can you unda-stend a Finn, or a Leplender, or a Oshkosher, huh?

Ignatz. No.

Krazy. Can a Finn, or a Leplender, or a Oshkosher unda-stend you?

Ignatz. No.

Krazy. Then I would say lenguage is that we may mis-unda-stend each udda.

Commentary like this had never appeared on the comics page before, and it attracted knowledgeable readers. Accompanying them were animators and toy makers, quick to seize on the strip’s freewheeling visual and verbal style. The Krazy Kat animated cartoons of the silent era captured Herriman’s eccentric spirit; once sound came in, the films became more commercial, and Krazy soon came to resemble the more popular Felix the Cat and, later, Mickey Mouse. The toys varied from tea sets to stuffed dolls suggesting the assembly line rather than the artist’s studio. Nonetheless, the royalties vastly increased Herriman’s income. In the 1930s, he relocated his family to Los Angeles, where they lived in a large Spanish-style house overlooking the Hollywood Bowl.

As before, Krazy remained the marquee name. Herriman stayed out of sight, known only to a few fans. One of those, however, happened to be a prominent book editor. Doubleday was planning to issue a volume called archy and mehitabel, written by the much-admired newspaper columnist Don Marquis. There was a reason for the lowercase title. The entries were supposed to have been written by archy, a free-verse poet reincarnated as a cockroach who was too small to capitalize letters by holding down the typewriter’s shift key. Philosophy was archy’s strong suit:

i was talking to a moth

the other evening

he was trying to break into

an electric light bulb

and fry himself on the wires

why do you fellows

pull this stunt i asked him. . . .

The moth replies that his kind crave the beauty of fire; better to be “burned up with beauty” than to live a longer, unbeautiful life. Then he kills himself on a cigar lighter. “i do not agree with him,” archy says. “but at the same time i wish / there was something i wanted / as badly as he wanted to fry himself.” archy also dabbled in lit crit:

coarse

jocosity

catches the crowd

shakespeare

and i

are often

low browed

Other critics make aesthetic excuses for Shakespeare’s frequent coarseness, archy continued. The truth, though:

but bill

he would chuckle

to hear such guff

he pulled

rough stuff

and he liked

rough stuff

Like Ignatz, archy had a feline associate: mehitabel, also a poet. Herriman had shown a matchless ability to caricature two-, four-, and six-legged animals, and Doubleday signed him up to illustrate Marquis’s poems. It was an ideal marriage; the artist’s dark, whimsical lines transformed the cockroach into an appealing bard and his crosshatched companion into a bawdy comedienne. archy and mehitabel hit the bestseller list, prompting Doubleday to issue several more collections. The final one was published in 1935, two years before Marquis’s death. Then, as before, the author got the ink and the artist remained in obscurity.

That was one reason why, by the early 1940s, Krazy Kat began to lose its momentum. The other was World War II. Military adventurers and caped crusaders took over the comics page, pushing screwball whimsy to the margins. Most of King Features’ strips appeared in hundreds of outlets; the Kat fanciers diminished until only 35 papers remained. Yet Herriman’s work persisted because of one devotee: William Randolph Hearst. Those who know Hearst only from his portrayal in Citizen Kane may not know that he had a sense of humor and a respect for imagination. Citizen Hearst overrode complaints by young editors who didn’t understand the events in Coconino County, and Herriman remained in business to the end.

Alas, it wasn’t long in coming. His wife was killed in a car crash, and his younger daughter died suddenly at 30. Herriman drew on, living in mournful solitude, surrounded by five Scotties: Angus, Shantie, McTavish, Macgregor, and Ginsberg. He died in 1944 of “non-alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver.” The death certificate listed his race as “Caucasian.” The following week, Herriman’s surviving daughter received a letter calling him “one of the pioneers in the cartoon business” and saying that his “contributions to it were so numerous that they may well be never estimated.” The letter was signed “Walt Disney.”

When a comic-strip creator died or retired, King Features usually hired other hands to carry on. Not here. Hearst knew that no combination of artists and writers could possibly reproduce Herriman’s lines. The Kat had used up all nine lives—or so it seemed.

Then, in 1946, an anthology of past strips appeared, along with a tongue-in-cheek introduction by one of America’s major poets. E. E. Cummings praised Herriman for his deep symbolism: “The meteoric burlesk melodrama of democracy is a struggle between society (Offissa Pupp) and the individual (Ignatz Mouse) over an ideal (our heroine).” Cummings’s endorsement was followed by many others. Beat writer Jack Kerouac said that Krazy Kat reflected “the glee of America, the honesty of America, its wild, self-believing individuality.” Oscar-winning film director Frank Capra called Herriman “one of the first intellectual philosophers to comment entertainingly and shrewdly on life’s frustrations through the medium of the comic strip.” Painter Willem de Kooning and Doonesbury cartoonist Garry Trudeau acquired original Herriman strips. When a small New York gallery held a Herriman retrospective, New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer wrote that the drawings there were “likely to look more like classics than a good many paintings and sculptures that are nowadays on view.” Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts, recalled that “after World War II . . . it became my ambition to draw a strip that would have as much life and meaning and subtlety to it as Krazy Kat had.” Author Jay Cantor resurrected the strip in a postmodern novel that took place in a post-nuclear world, complete with X-rated interludes. The Italian novelist Umberto Eco topped them all, comparing Herriman’s daily output with the stories of Scheherazade.

Though Herriman dodged the spotlight, he found posthumous celebrity—or, more accurately, it found him. Some of this was inevitable: in an epoch of pop-culture studies, articles and dissertations parsed the meanings in Herriman’s strip. The androgyny of Krazy Kat, of course, was a natural for academic analysis. In the bimonthly Postmodern Culture, a University of Virginia professor notes that “most of Krazy’s activity is not gender-specific, but in scenarios involving some complication of his normal relationship with Ignatz, Krazy adopts whichever gender role will restore the usual balance.” Freudian interpretations abound, with Krazy, Ignatz, and Offissa Pupp as cartoon versions of the id, ego, and superego.

The true revival, however, lies outside academia. Herriman’s original drawings for the dailies routinely sell for $25,000; the four-color Sunday spreads go for much more. The archy books have never been out of print. In 1995, the U.S. Postal Service put Krazy on a 32-cent stamp. Shortly afterward, Comics Journal, a publication devoted to the art form, rated Krazy Kat the best American strip of the twentieth century. Currently, more than 20 Herriman compilations are available on Amazon, ranging from The Kat Who Walked in Beauty: The Panoramic Dailies of 1920 to Krazy Kat & the Art of George Herriman, a lavishly illustrated homage. The animated shorts, once nearly impossible to find, have been issued on DVD under the titles The Krazy Kat Kartoon Kollection and Kinomatic Krazy Kat Kartoon Klassics. (Evidently, when writing about the Kat, a tendency to substitute Ks for Cs is irresistible.)

And a generation after Herriman’s death, his ethnicity was at last unearthed by genealogical researchers. Now, black historians claim him as one of their own, calling him the first great African-American pop artist.

For decades now, fans, writers, and scholars examining the Herriman oeuvre have stressed the “outrageous,” the “eccentric,” and the “zany” in his work. This emphasis is misplaced. Anyone who reads a newspaper or watches cable TV understands an incontrovertible fact: for all their antics, Krazy, Ignatz, and Offissa Pupp perform for a world far loonier than anything their inventor ever konceived.