Savage terror attacks in recent years have killed thousands of people in the United States, Western Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. The increasingly brazen acts, while violent and tragic, have been limited in scope because of the terrorists’ dependence on conventional weapons—firearms, vehicles, and homemade bombs. After each incident, a familiar sequence of responses ensues: politicians call for resolve; civil authorities and residents work to clean up the damaged area; medical personnel give aid to the victims; shopkeepers and merchants reopen. And almost everyone outside those directly affected moves on, hoping that terror won’t call their number in the future. Getting on with life makes sense, of course, but complacency about terrorism looms as a serious problem in free societies—especially since future terrorist threats hold the potential to shake the foundations of our society. The overwhelming evidence—from Osama bin Laden’s hard drive to incessant ISIS tweets—is that our jihadist enemies are determined to break through conventional limitations on death-dealing and do us even more grievous harm.

Of all the types of unconventional threats we face, bioterror may be the most worrisome. The danger is especially pressing for high-visibility areas such as Washington and, especially, New York. Gotham’s centrality as a cultural and financial center, along with its size and symbolism, makes it a more desirable target for jihadists than any other city. According to a Heritage Foundation breakdown of 74 failed terrorist plots against the United States between 9/11 and 2015, 16, or 22 percent, targeted New York, more than any other U.S. city—one reason that New York felt the need to create its own antiterror unit. (Another reason: city officials didn’t trust federal law enforcement and intelligence entities to give the NYPD actionable intelligence on a timely basis.)

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Biological attacks are disease outbreaks on steroids, requiring a speed and scope of response much greater than typically needed for natural infectious-disease events—or conventional terror. Responding to bioterror in New York would present particularly significant challenges because of the city’s size, population density, and transportation issues.

Bioterror is widely seen as the stuff of movies and spy novels, but history shows that it’s all-too possible—and that law enforcement is ill equipped to prevent or even to prosecute it. Thus far, America has seen few genuine bioterror incidents (and none that matches the dark plots in Tom Clancy novels). Yet even these rare and not terribly sophisticated attacks have made an impact.

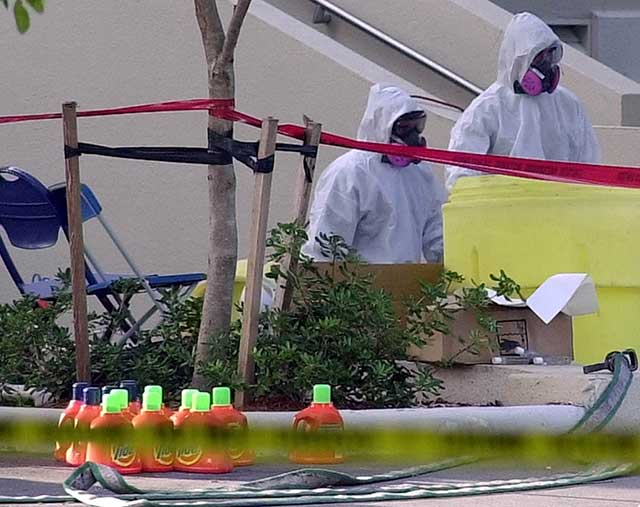

The Chicago Tylenol poisonings of 1982, for example, used cyanide, not a biological agent, but still killed seven people, panicked a nation, resulted in 32 million bottles of Tylenol getting pulled from the shelves, and changed product-safety packaging forever. In 1984, members of the Buddhist Rajneeshee cult spread salmonella out of plastic bags at restaurants in The Dalles, Oregon, east of Portland. The cult wanted to influence local elections and hoped that poisoning non-cult members would improve their electoral prospects. The poisonings sickened about 750 people and hospitalized 45. Fortunately, none died. The 2001 anthrax mailings killed five, injured members of the media, shut down the Capitol, threw the U.S. postal service into turmoil, and sent Americans looking for Cipro prescriptions in anticipation of the next dispersal. The Tylenol villain was never identified; the anthrax culprit was also never definitively identified, despite what Kelly McKinney, former deputy commissioner at the New York City Office of Emergency Management, called “one of the largest and most complex investigations in the history of law enforcement.” And in the Oregon cult example, federal officials caught the perpetrators only after they admitted what they had done. As these examples make clear, it is exceedingly hard to prevent or detect bioterror, let alone catch the perpetrator.

Another fearsome aspect to bioterror is the massive damage that it can potentially cause. Dark Winter, a 2001 simulation exercise by the federal government, gamed out what would happen in a smallpox outbreak for which the nation was unprepared. The exercise used actual U.S. vaccine stockpile figures to determine its parameters; officials had enough vaccine for only 5 percent of the U.S. population, and 1 million Americans “died” in just 68 days. In 2009, a National Security Council assessment put potential deaths from an anthrax attack in the “hundreds of thousands,” and the economic cost at more than $1 trillion.

Experts worry that such scenarios have become increasingly more plausible. As the shock of terror wanes from its awful regularity, terrorists may feel the need to intensify the fear that they generate. “At some point, these methods will no longer be as novel or effective in sowing fear as they have been,” Columbia’s Stephen Morse told me, “fueling terrorists’ temptation to overcome the technical and perceptual barriers and move to more dramatic means.” Similarly, former White House biodefense aide Robert Kadlec notes: “While terrorists have not used biological agents in terrorist attacks yet, the trends indicate more terrorist groups are interested in conducting such attacks.”

Terrorists’ development of weapons is a much scarier concern than their acquiring of weapons. “When we talk about terrorists’ acquiring a nuclear weapon,” says former Navy secretary Richard Danzig, “we’re talking about just that—they’re acquiring a weapon. With biological weapons, we’re talking about acquiring the ability to produce weapons.” Once that ability exists, Danzig says, “You really have to think about biology as potentially the subject of a campaign, where somebody keeps attacking, rather than a one-shot incident.” Morse compares bioweapons knowledge to learning how to assemble improvised explosive devices (IEDs): “Once a few well-connected people learn how, they can teach others.”

Developing the capability is difficult but far from impossible. As former Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) director Brett Giroir told the New York Times, “A person at a graduate-school level has all the tools and technologies to implement a sophisticated program to create a bioweapon.” New technologies are making the terrorists’ job easier. According to Kelly McKinney, while “the technical requirements to develop and disseminate a biological agent are high . . . certain disruptive technologies are making it easier for the bad guys. We are hearing that in the not too distant future, these agents and devices could be brought together in a suburban basement.”

We cannot know the true impact of a massive bioterror event, but the evidence suggests that the United States is not yet ready for one. Former senator Joseph Lieberman and former Homeland Security secretary Tom Ridge cochaired a recent Blue Ribbon Panel on biodefense on which I participated. The panel concluded: “The United States is underprepared for biological threats. Nation states and unaffiliated terrorists (via biological terrorism) and nature itself (via emerging and reemerging infectious diseases) threaten us. While biological events may be inevitable, their level of impact on our country is not.”

According to Stanford’s Lawrence Wein, a successful anthrax attack in New York could cost 100,000 lives, with full decontamination taking more than 300 years. As Judith Miller wrote in City Journal nearly a decade ago, a major anthrax incident would test New York severely. (See “Bioterrorism’s Deadly Math,” Autumn 2008.) Miller found that New York’s distribution, transportation, and decontamination capabilities were all inadequate for bioterror. That other cities are similarly unprepared should be of little comfort, given New York’s prominence as a target.

Thankfully, New York has made major progress over the last decade, with heightened awareness and extensive planning and training programs in place—as well as its own biological-detection capabilities. New York’s Countermeasures Response Unit Office has built an extensive infrastructure, including “points of distribution (POD) sites, trained management and staff, materials and equipment, and supporting information-management systems,” McKinney says. Team members believed that they could “provide antibiotics to the entire population of New York City within 72 hours,” he observes, and large-scale training exercises seem to bear out this confidence.

New York recently tested its vulnerable subways as part of its preparatory efforts. In the spring of 2016, the city worked with the Department of Homeland Security to release an innocuous gas in the subways—on the Number 4, 5, and 6 lines—to measure its potential effects on airflow. Bob Ingram of the New York Fire Department’s Center for Terrorism and Disaster Preparedness said that the test was “extremely beneficial. We can all think about how this behavior is going to be, but this test will hopefully have enough data to back it up with science.”

And it’s not all tests: New York has seen its share of real-world disease outbreaks over the last decade, including inhalation anthrax in 2006, multiple hepatitis A exposures in 2008 and 2013, the H1N1 “swine flu” of 2009, Ebola in 2014, Legionnaires’ disease in 2015, and Zika virus in 2016. None of these approached the scale of a massive bio-attack, but each helped refine the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s capabilities. New York City has “planned, trained, and exercised in a regular fashion that, quite frankly, other cities have not,” says Kadlec, including being perhaps the only jurisdiction “to conduct a no-notice exercise.” With relentless focus and hard work, the city has made considerable strides in readiness.

Despite all of New York’s good work, serious vulnerabilities remain. On the prevention front, for example, environmental screening for airborne pathogens is a key form of detection—but particularly tough in New York, with its more than 240 skyscrapers, more than double that of any other U.S. city. (Chicago is the only other American city with more than 100.) Each one of those 240-plus skyscrapers is its own bioterror target, with vulnerable ventilation systems that could be used to spread a biological agent to thousands of inhabitants. Skyscrapers are more promising targets for bioterrorists than an outdoor environment; a closed-ventilation system avoids the vagaries of weather effects and ultraviolet degradation, maintaining full potency of the biological agent. Building managers are aware of the vulnerabilities, and most have security in place, but it’s easy to imagine a breach.

The sheer size of New York City is another hurdle. With five boroughs, 8.5 million people, and more than 300 square miles, even the city’s large and relatively well-prepared force of first responders has a lot of ground to cover. And in contrast to 9/11, bioterror would likely be spread out across the city, with multiple points of convergence. Navigating New York City traffic to get to the affected areas would be daunting. Further, the subways, which are vital to maintaining a manageable traffic flow, are notoriously hard to protect. Tests of biological-agent detection in American subways such as the one conducted in spring 2016 are helpful, but they have high failure rates. And government testing often cannot detect pathogens unless they are at stratospheric levels—well beyond the level necessary to be fatal.

Another form of detection comes from doctors and other health professionals. If hospitals detect unusual symptoms, especially multiple occurrences of specific symptoms, they notify the Centers for Disease Control. New York has 62 hospitals, including at least two where translators communicate in 150 languages. Health professionals in such a large city with a sizable transient population and a constant influx of visitors may be slower to pick up on an unusual disease vector. New York, recognizing its potential vulnerability, has put into place more active monitoring to detect unusual disease patterns. The New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene uses what’s known as a “syndromic surveillance system” to monitor unusual or alarming patterns that could emerge from emergency-room activity, first-responder calls, and over-the-counter medication sales. But the task remains formidable.

The federal agencies in charge are highly bureaucratized and not always nimble in response. McKinney worries about the sizable gap between the city’s preparedness and that of state and federal officials, who, having done much less, “will bring an enormous amount of chaos and confusion with them.” New York will have to do more to bring about cooperation with entities that may be less focused on bioterror. The city must demand more cooperation and focus from the state and localities and work to ensure that its preparedness exercises include state and federal officials.

One intangible factor: civic culture and the character of residents. New Yorkers pride themselves on toughness—sometimes to the irritation of the rest of the country—and they have shown a willingness to soldier on through the most unusual circumstances, as they do through other hazards of daily life in the Big Apple. If the famous New Yorker resilience could help against a real pathogen, the city would have little to worry about.

“Unlabeled, secret stockpile warehouses are strategically placed at 12 locations throughout the country.”

Some of the issues regarding New York’s size and complexity are compounded when it comes to responding to bioterror. The foundation of U.S. bioterror-combating strategy is based on the accumulation of countermeasures in the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), which would be rapidly distributed when needed.

The SNS, containing about $7 billion worth of countermeasures, costs the U.S. about half a billion annually to develop and maintain. The materials include vaccines, responsive agents such as antivirals, and tools for first responders, such as respirators, as well as agents to respond to radiation and chemical attacks. The exact nature of the products in the SNS is classified, for good reason. “If everybody knows exactly what we have, then you know exactly what you can do to us that we can’t fix,” says SNS director Greg Burel. “And we just don’t want that to happen.” The SNS locations themselves look like large, nondescript warehouses. “If you envision, say, a Walmart Supercenter and stick two of those side by side and take out all the drop ceiling, that’s about the same kind of space that we would occupy in one of these storage locations,” says Burel.

For the most part, the stockpile has what experts think it needs: for example, 300 million treatment courses for smallpox, enough for every citizen, and enough anthrax vaccine to handle a three-city incident. In fact, the U.S. hired a consulting firm, Gryphon Scientific, to evaluate whether it was stockpiling the right products; Gryphon concluded that it was. According to the firm’s Rocco Casagrande, “one thing we can say is that across the variety of threats that we examined, the Strategic National Stockpile has the adequate amount of materials in it and by and large the right type of thing.”

A stockpile is useful only if it can get materials where they need to be in a crisis. The SNS is very effective at enabling government officials to send needed countermeasures anywhere in the United States on short notice, thereby reducing the danger of a bio-strike spreading out of control. Unlabeled, secret stockpile warehouses are strategically placed at 12 locations throughout the country to ensure the efficient delivery of supplies. The goal: to be capable of getting crucial countermeasures to any location in the country within 24 hours.

Then the materials have to be distributed effectively. Currently, the primary method for dispensing SNS supplies is by the Points of Distribution (POD) system. Other possible distribution methods exist, such as using the postal service or encouraging the purchase of home med kits. New York’s planners assume, though, that postal workers would not show up for distribution in a bioterror scenario. Even if they did, the city acknowledges that it lacks the capability to keep them safe. As for home med kits, paternalistically minded public-health officials tend to be skeptical of giving individuals autonomy over the purchase of countermeasures for their own consumption. It is thus likely that a POD would be the primary distribution method.

In the POD approach, the drugs are delivered to a central location (schools and other public spaces), and people must access them on their own. This method raises significant concerns. First, it discriminates against those who lack the means to transport themselves to the pickup spot. Second, the POD method is also a “blind” distribution: aiming for fairness, it does not necessarily target those who need the countermeasures the most, such as members of a particularly high-risk population. The government does draw up lists of primary recipients—including first responders, vulnerable populations, the military, and some key government officials—but POD-based distribution does not lend itself easily to that kind of prioritization. The danger of insufficient supplies at a distribution center during a tense period is potentially combustible and could lead to unrest. Third, some countermeasures may require a qualified health professional to administer, which complicates the question of staffing the distribution centers.

In recent years, New York has engaged in exercises to ensure that public-health officials are ready for a possible citywide distribution of emergency countermeasures. In a surprise citywide bioterror drill in August 2014, 1,500 city employees from 13 agencies set up 30 distribution sites across the city in less than eight hours. Overall, New York’s health department has trained more than 3,000 employees in the establishment and operation of PODs. Recognizing the transportation difficulties that would emerge, city planners have wisely assigned staffers to distribution locations near their own homes. The test persuaded the CDC to take the groundbreaking step of forward-deploying assets from the SNS into New York’s own stockpiling warehouse in order to avoid an additional step in distribution.

New York’s relevant experience also offers some encouragement. In 2009, for example, during the H1N1 influenza, New York administered vaccines to 195,000 schoolchildren at 1,200 New York schools, as well as 50,000 additional individuals at 29 locations across the city. Going further back, in 1947, New York’s Department of Health vaccinated more than 6 million New Yorkers during a minor smallpox outbreak. The vaccinations took place at 179 clinics and benefited from the cooperation of key groups in the city, including doctors, labor unions, and local businesses. Of course, New York’s population has increased by 2.5 million people since then—more than the total population of all but two other U.S. cities: Los Angeles and Chicago.

With a population the size of New York’s, telling inhabitants what to do and where to go won’t be easy. With all the progress in new communications technologies of recent years, many still fail in times of crisis. After 9/11, for example, telephone circuits were overloaded. New York has faced such obstacles before. In 1999, the city set up a hotline for residents worried about the outbreak of West Nile virus. The network responded to more than 150,000 queries over seven weeks. In the case of bioterror, officials would need to reach out to many more individuals over a much shorter period of time.

Cross-community cooperation—that is, how well people will respond, work together, and obey authorities—is also crucial. The 1965 New York City blackout, which affected 30 million people across the Northeast, was recalled nostalgically as a pleasant hiccup by city residents. People got along splendidly (arrest totals that day were below average), the power was restored in about 13 hours, and some later tittered that the hospitals saw a slight baby boom nine months later. Just 12 years later, though, on July 13, 1977, three separate lightning bolts struck and destroyed three power lines in Westchester County, New York, leading to a very different blackout experience, with more than 1,600 stores looted or damaged, more than 1,000 fires, and more than 3,700 people arrested. The mayhem caused over $300 million in damages. Part of the reason for the contrast was a breakdown of social norms in the intervening years. New York in 1977 was a very different place from what it had been in 1965—more crime-ridden, more volatile, and struggling to overcome bankruptcy.

While New York in 2017 is dramatically safer than it was in 1977, it is still a far different city from what it was in 1965—or in 1947. Bioterror response plans count on the cooperation of a pliant populace to show up at PODs or vaccination clinics. It’s not at all clear that New Yorkers today could be classified as pliant. The problems we have seen recently in terms of the tensions between the police and Mayor Bill de Blasio, as well as ongoing protests from groups such as Black Lives Matter, point to a worrisome level of distrust between authorities and some of the populace.

Some authorities even seem conflicted themselves, seeing emergency situations as periods in which police forces accrete dangerous powers. Less than a year after the 2001 anthrax episode, the New York Civil Liberties Union’s Robert Perry testified about the Model Emergency State Health Powers Act (MESHPA), a draft bill that would give states additional powers in the case of a public-health emergency. Perry warned that “government, acting in the name of public safety, has demonstrated bad judgment, and worse, using state police powers in a discriminatory manner to suspend freedoms based upon race or national origin.” He saw the bill’s definition of a public-health emergency as “overly broad” and warned that it “fails to clarify sufficiently the circumstances that would justify the declaration of such an emergency.” On the right, Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum denounced MESHPA as a “Totalitarian bill on health pending in your state!” MESHPA is hardly faultless legislation; but the pushback against it from the Right and the Left illustrated how government actions in a true public-health emergency could face skepticism, lawsuits, and other actions that may impede government’s ability to respond.

Where does that leave us? Looking to New York’s considerable assets—its unmatched police and counterterror forces, its centrality to Homeland Security planning, its resources, and its people—there are reasons to believe that the city would prove equal to bioterror, should it happen. Yet given the existential crisis that such an attack would present, New York must remain ever vigilant to keep its residents safe.

Top Photo: New York’s more than 240 skyscrapers are particularly vulnerable to bio-attacks through their ventilation systems. (VOLKAN FURUNCU/ANADOLU AGENCY/GETTY IMAGES)