Even now, making our twenty-first-century rounds, we’re never far from the reach of the Fancy. Outside Grand Central Terminal on a raw spring morning, the UPS drivers are doing their moves: one guy, slight and older, crouching and bobbing his head, his breath making clouds in the chill air, throws hooking punches, left and right, which stop just short of the larger and younger man, who tucks in his elbows as if he were tapping his ancestors’ instincts: protect the body, move your feet, position yourself to be ready when the chance comes. The scrap ends almost as soon as it began, the men laughing.

Politicians, pledging to “fight” for a principle, sometimes hold up boxing gloves as a sign of commitment to cheering supporters. The gloves bring to mind a familiar image: a narrow, roped square; eager spectators surrounding the ring; and, in the fighters’ corners, old, wrinkled seconds with Q-tips behind their ears, holding buckets. The scene frames an odd, brutal human activity that disappears from the public mind for long periods, then surfaces again when a fight or fighter reaches out to us, demanding a response.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

But that happens rarely today; few Americans could name more than one or two current boxers, if that. Boxing has become a ghost sport, long since discredited but still hovering in the nation’s consciousness, refusing to go away and be silent entirely. There was a time when things were very different. For boxing once stood at the center of American life, and its history winds a thread through the broader history of the nation.

Boxing’s beginnings in America go back to slave days, when plantation owners pitted slaves against one another and wagered on the outcomes. One freed slave, Tom Molineaux, even fought overseas against the British champion, Tom Cribb—and probably would have won their 1810 match, had Cribb’s desperate supporters not intervened just as Molineaux seized a decisive advantage. Boxing then was conducted with bare fists, under the old London Prize Ring Rules, which stipulated fights to the finish—that is, until one man could not continue. The rules also permitted wrestling holds and other tactics, and rounds ended only with “falls,” when one man went down, whether from a punch or a throw or sheer exhaustion. Before the Civil War, boxing enjoyed a brief vogue in New York, where fighters often associated with the Tammany Hall machine rose to prominence. But the war interrupted the sport’s momentum.

Only with the emergence of its first great figure, John L. Sullivan, did boxing truly arrive in America. Born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in 1858, the son of an immigrant hod carrier from Ireland, Sullivan fought his way to wealth and fame rivaled by few in his time. With his physical prowess and hot-blooded public persona, Sullivan became an Irish-American hero and a symbol of manly vigor to a nation that, experiencing an industrial revolution and transformative changes in living standards and manner of work, worried that its young men might go soft. After he won the heavyweight championship (or at least what Americans generally viewed as the championship) in 1882, he went on a barnstorming national tour, offering $1,000 to anyone who could last four rounds with him in makeshift rings set up in theaters, ballrooms, and saloons. Reportedly, only one man won the money. It’s from Sullivan that we get the boast, still heard today: “I can lick any sonofabitch in the house.”

Sullivan created an archetype that remains in force in 2011: the athlete as cultural icon and all-around moneymaking machine. In Sullivan’s time, that dual role generally meant performing on stage, as he did in Honest Hearts and Willing Hands, a melodrama that toured the country. “Shake the hand that shook the hand of the great John L.!,” exulted the lucky few who got to meet him. Poet Vachel Lindsay memorialized Sullivan’s most impressive victory, in an 1889 marathon battle with Jake Kilrain—the last bare-knuckle championship, waged in wilting heat and lasting over two hours.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, boxing remained broadly illegal. To avoid legal scrutiny, Sullivan and Kilrain fought on a lumberman’s estate just south of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, a rural location revealed only to partisans of the sport known as the Fancy. But before Sullivan’s career ended, boxing had moved into the cities, where the gyms, matchmakers, managers, trainers, and promoters were, as well as athletic clubs and arenas for holding the fights. In New York, for instance, while the sport’s legal status was contested for decades, fights nonetheless took place, often as “exhibitions” or sparring demonstrations.

Over time, eastern opponents of the sport pushed its locus to cities in the south and west. In 1890, New Orleans legalized boxing under the Marquis of Queensbury Rules, which mandated the use of gloves and three-minute rounds, a ten-count for a fallen fighter, and increased oversight powers for the referee. And it was under those rules, still in effect today, that Sullivan fought in 1892 at the city’s Olympic Club—illuminated by newfangled electric lights—and lost his title to the young, slick James J. Corbett, who would eventually win international recognition as heavyweight champion.

Boxing’s center of gravity, especially in America, quickly became the heavyweight division, whose champion was seen by the public as a symbol of American masculinity. It mattered to Americans who claimed that distinction, as proved all too clear in 1908, when Jack Johnson, a black man, won the title. Johnson aroused opposition even before the championship fight was over. As he pummeled reigning champ Tommy Burns, police stormed the ring to stop the fight, and film cameras were shut off to spare the world the sight of a black knocking out a white for the crown. Jack London, writing at ringside, immediately issued a call for retired champion James J. Jeffries to return to the ring, “wipe the grin off Johnson’s face,” and reclaim whites’ pride. Thus was the nation set on a crusade to find a White Hope to defeat Johnson. But he was too good. Inflaming passions further, Johnson made a point of enjoying himself inside the ring, where he often openly mocked his opponents, as well as outside it, where he drove sports cars, wore expensive clothes, frequented nightclubs, and (worst of all for white America) kept intimate company with white women. When Johnson easily defeated the once-great Jeffries in Reno on Independence Day 1910, cities across the nation erupted in race riots. Fearing future unrest, Congress banned the interstate transport of fight films, a law that remained in force for more than a quarter-century.

Johnson’s brazenness put him in the crosshairs of the U.S. government. In traveling with one of his white consorts, officials charged, Johnson had violated the recently passed Mann Act, which outlawed transporting women “for the purpose of prostitution, debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” The charges were dubious; the law was intended to thwart human trafficking, and though Johnson’s lovers were often prostitutes, the relationships were consensual. Still, Johnson took no chances, jumping bail and living out the rest of his championship reign in foreign exile. In 1915, in Havana, he lost the title to Jess Willard, a giant White Hope recruited expressly for the purpose of beating him. A generation would pass before another black fighter was permitted to challenge for the heavyweight crown.

During Johnson’s long reign, and for a time after it, boxing’s future was uncertain. New York City continued to vacillate, most states still banned the sport, and it lacked a central, unifying figure. That all changed with two seismic forces: American entry into World War I and Jack Dempsey. The American Expeditionary Forces boxed extensively for recreation and training in their barracks in France, and General John Pershing praised the sport’s benefits for young men. Knowing that the doughboys had just faced the kaiser’s guns, Americans found it hard to object to their right to box back home for pay. The summer after the war ended, Dempsey burst onto the national scene, winning the heavyweight title from Willard on a scorching July 4 in Toledo, Ohio.

Dempsey’s arrival closed the circle of eras old and new. His parents had come west, to Manassa, Colorado, in a covered wagon in the 1880s; he’d worked in mining camps in states barely past their frontier days; and his title-winning fight was policed by the aging Old West lawmen Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp, who collected firearms and knives from spectators before they entered the arena. But Dempsey would inaugurate America’s modern age of sports and become a focal point of its dawning celebrity culture. He fought with a ferocity that boxing had never seen—demolishing much larger opponents in just minutes, earning himself nicknames like “the Giant Killer” and “the Manassa Mauler,” and igniting a frenzy of popular interest. In 1921, Dempsey’s match against a French war hero, Georges Carpentier, drew more than 80,000 fans into a wobbly, custom-built wooden bowl in Jersey City. They paid $1.7 million in gate receipts—boxing’s first million-dollar gate—and the event captured global headlines. The Radio Corporation of America made its debut that day, transmitting the fight over primitive “radiophone” technology—radio’s first mass broadcast in the United States.

Such unheard-of crowds and profits ended boxing’s shadow existence and ushered in its golden era, which would last through the 1950s. Within a year of Dempsey’s winning the title, New York State legalized boxing for good, and during the twenties, laws against the sport were overturned in state after state. New York quickly became the capital of boxing, with Madison Square Garden its most celebrated venue and Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds hosting huge outdoor crowds for summer matches. Dempsey is often mentioned today as a footnote to his Roaring Twenties sports peers Babe Ruth and Bill Tilden, but he rose to fame before they did and made so much more money—his richest single-fight purse nearly equaled Ruth’s career earnings—that it seems unfair to equate him with anyone. He grew so wealthy that he took three years off from the ring to try his hand at films and the stage. In 1926, his bout with Gene Tunney in Philadelphia drew a record 120,000 fans, who watched in a driving rain as Tunney won the title. The New York Times announced the shocking result in a three-tier, seven-column, front-page headline the next day. The following year, the two men drew more than 100,000 to Chicago’s Soldier Field for the rematch, which Tunney also won, and set a gate-receipts record that stood for half a century.

Dempsey and Tunney retired in the late twenties, and soon afterward, the stock-market crash portended harder times after a decade of spectacle and excess. Mediocrity characterized the heavyweight division during the early 1930s, but boxers in the lower weight classes kept the sport going. The thirties also saw the peak of boxing’s ethnic rivalries: Jewish boxers like Barney Ross, Irishmen like Jimmy McLarnin, and Italians like Tony Canzoneri combined thick immigrant cultural ties with mainstream appeal, illustrating the centrality of boxing in American life.

With the advent of Joe Louis, who first gained national prominence in 1935 and became heavyweight champion two years later, the heavyweight division returned to center stage. Louis was the first black man since Johnson to get a shot at the title, after a steep climb out of poverty and the social deprivation that American blacks once endured as a matter of course. A grandson of slaves, he was born in Alabama but moved north with his family, settling in Detroit’s Black Bottom ghetto—so named not for its population but for its dark soil—where he began boxing when still a boy. Unlettered and wary in the public eye, Louis fought in a deliberate, methodical style, always in position to punch and to defend, unhurried but moving toward what came to seem inevitable: another knockout win.

Louis faced adversity of the kind that today’s black athletes can only imagine. Remembering how Johnson had alienated whites, Louis’s management team installed a set of rules for his conduct. These included a ban on being photographed with white women and a public posture of stoicism and clean living. A generation later, more militant blacks, like Muhammad Ali, would suggest that Louis had been too accommodating of white sensibilities, but their criticism betrayed a lack of understanding of the social context. Blacks were still getting lynched in the South; Louis seemed to understand his opportunity, and he didn’t waste it.

At Yankee Stadium in June 1938, Louis met Germany’s Max Schmeling in what remains the most politically charged sports event ever held. Schmeling had become a favorite of the Nazis—not as eagerly as his critics insisted, not as reluctantly as his apologists would later claim—and they often cited his earlier victory over Louis as proof of Aryan supremacy. Here was one of history’s surprises: most of pre–civil rights white America rooting for a black man against a white boxer. Louis, though black, now became America’s representative, as confirmed by a White House visit with Franklin Roosevelt, who told him that the nation was relying on him. Almost half of America’s population—60 million people—tuned in to the radio broadcast. What they heard NBC announcer Clem McCarthy describe was probably the supreme example of an athlete executing under pressure. And “execute” is the right word: Louis finished Schmeling off in barely two minutes.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Louis defended his title twice more, donating his purses to the Army and Navy Relief Funds, before entering the Army himself in 1942. The tribute paid him by sportswriter Jimmy Cannon—“A credit to his race, the human race”—sounds condescending now, but it reflected the impact that Louis had on white perceptions. When Louis finally retired from boxing in 1949, he had held the title for nearly 12 years, the longest run in boxing history.

Louis’s departure came at a time when boxing probably had its strongest hold on American sporting interest. In television’s early years during the fifties, prime time featured fights nearly every night of the week, the most dependable fare for two major sponsors, Pabst Blue Ribbon and Gillette. Fans saw a worthy successor to Louis in Rocky Marciano, an Italian-American from Massachusetts, who would become the only heavyweight champion to retire without a defeat. In the lower weights, the unparalleled Sugar Ray Robinson—who lost only once in his first 132 fights—would win, lose, and win again the middleweight title in a series of dramatic bouts. He also made himself into a Harlem institution with his pink Cadillac; his nightclub, Sugar Ray’s; and his traveling entourage, which included a masseuse, a barber, a voice coach, a golf instructor, and a dwarf mascot, among other essential personnel.

By the time Marciano and Robinson departed the scene, the sport’s ethnic makeup had altered dramatically from the days of Dempsey and Louis. More than any other sport, boxing had always drawn its ranks from the poor, and as postwar prosperity expanded the middle class, the stock of Irish and Italian fighters began thinning out, while the Jewish fighters were all but gone. Hispanic fighters, like Cuba’s Kid Gavilan, became a presence in the U.S., while blacks took the lead. It was all part of the nation’s changing social landscape.

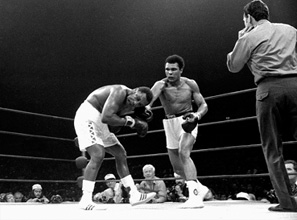

But nothing could have prepared America for the sixties—or for Muhammad Ali, as divisive a figure as that traumatic decade produced. Even before he became politically vocal, Ali, originally named Cassius Clay, carried on like no American athlete before him, declaring that he was “the Greatest” boxer of all time and reciting doggerel poetry predicting the outcomes of his bouts. Unlike most great heavyweights, he won not with heavy punching power but with the speed of his hands and the balletic grace of his feet. So artful and quick was he that he never bothered to learn the rudiments of defense, instead keeping his hands low and often leaning away from an opponent’s punches instead of blocking them. “His hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see,” he said. Though purists dismissed his performances inside the ring and out, there was a refreshing exuberance to the young boxer. Absurdly handsome for a fighter, he was a sporting herald of the emerging youth culture; he won the heavyweight title in February 1964, the same month that the Beatles landed in America.

But that year, he announced his membership in the Black Muslim movement and changed his name, and in 1967, he refused induction into the U.S. armed forces for service in Vietnam. Ali became a pariah, loathed by many white fans and most established sportswriters. Claiming conscientious-objector status, he saw his boxing license revoked across the country, and for three and a half years found himself banned from the ring and facing numerous legal battles. Only in the 1970s, by which time he’d been reinstated to fight, did he make inroads with more conservative fans. With the war over and the nation trying to come to terms with its shattering effects, Ali’s trajectory now seemed less radical. Even his critics had to admit that he had paid a steep price, losing the prime years of his athletic career. On returning to the ring, he faced two defining adversaries—Joe Frazier and George Foreman—and the pure theater of his battles with them has never been surpassed. As Ali aged and slowed but kept fighting anyway, his fights became mesmerizing dramas of gamesmanship, skill, and, finally, sheer grit. In the ring, he made converts of everyone. He seemed to have more to fight for than his opponents did, not only because his surpassing ego made him willing to endure anything to win, but also because, in casting himself as a racial prophet and champion of the world’s downtrodden, he made it so that he must not lose.

Ali discredited forever the idea of the quiescent athlete, and he was the first truly global sports star. His unmatched gifts as a showman have influenced athletes in all sports, though mostly not for the better: the athletes who mug before the camera, celebrate themselves at every turn, and denigrate opponents are part of Ali’s legacy. In a popular culture addicted to display, those who prefer to keep their thoughts to themselves are now suspect for lacking authenticity. Still, in his sport’s history, Ali is a colossus without successors: he fought like no one before or since.

In his usual grandiose way, Ali predicted that boxing would die after he was gone, but for a decade after he left the scene, the sport enjoyed its last great run. The public’s interest turned once again to fighters at the lower weights. This shift was sparked by a gifted boxer from Maryland, Ray Charles Leonard, whose parents named him after the singer but whose boxing tutors cheekily gave him Sugar Ray Robinson’s famous nickname. Articulate, usually gracious, and not given to shouting, he was Ali without the politics or the sometimes cruel theatrics. But like Ali, he would prove himself against the highest level of competition. In the 1980s, Sugar Ray Leonard and his formidable adversaries—Roberto Durán, Thomas Hearns, and Marvin Hagler—fought one another in a series of high-profile bouts that made them all multimillionaires. And Leonard would prove more successful than Ali at retaining his earnings and his faculties.

Just as Leonard and the lower-weight heroes of the eighties were finishing their careers, Mike Tyson emerged as the next great heavyweight, and boxing again had a focal point in its marquee division. Tyson’s worldwide fame would approach Ali’s. A violent youth from Brooklyn’s Brownsville neighborhood, Tyson was legally adopted by the enigmatic trainer and boxing psychologist Cus D’Amato, who saw a future heavyweight champ in the hulking 13-year-old and made him his personal project. D’Amato’s judgment proved correct in 1986, as Tyson, just 20, became the youngest man to win a heavyweight title.

What made Tyson fearsome in the ring was not just his terrifying punching power but his speed. No heavyweight combined the two assets so formidably. In the early years of Tyson’s reign, most opponents were, in effect, beaten before the opening bell, so intimidating was his aura. His Dempsey-like style of early-round knockouts made his name box-office gold. Tyson also won the goodwill of the American public, thanks to an earnest personality—including an inimitable high-pitched voice—and an expertly managed public-relations image. Sportswriters called him Kid Dynamite.

But it turned out that the soft-spoken kid with the killer punch had demons that had never been conquered. As his fame and wealth grew, Kid Dynamite gave way to Tabloid Mike. His doomed marriage with a young actress, Robin Givens, made fodder for headlines and ended amid lurid tales of domestic violence. As his personal life spiraled out of control, Tyson lost his focus in the ring. He lacked Ali’s force of will and ability to improvise, and he lost his title at 23. Not long afterward, he was convicted of rape and served three years in prison.

On his release, promoters eagerly paid Tyson millions to box again, but Kid Dynamite couldn’t regain his youthful form. Embracing the role of villain, he became one of the more grotesque figures in America’s always bizarre popular culture, uttering statements like “I want to kill people. I want to rip their stomachs out and eat their children.” Nothing captured Tyson’s depravity more memorably than his 1997 fight with Evander Holyfield, in which he bit off pieces of his opponent’s ears, earning a disqualification and provoking a wild postfight melee.

Tyson’s behavior sullied boxing’s always precarious reputation, making the sport synonymous with freakishness. He would be the last in a long line of heavyweights to bear a symbolic connection to American social trends. For just as the blustery John L. Sullivan represented a growing nation coming into its strength, and the magnetic Dempsey the birth of mass-media celebrity and commercial culture, and the stoic Louis the hard years of depression and war, and the mercurial Ali the age of rebellion and change, so Tyson embodied the postmodern hoodlum—the gangsta from an urban landscape pulverized by fatherlessness and anomie. Remarkably, a middle-aged Tyson is now trying to remake his life, a feat that, given the obstacles, would outstrip anything that his illustrious predecessors achieved, in the ring or out.

With Tyson’s fall, boxing completed its transformation from central preoccupation to sideshow. For years, the sport had failed to meet the competitive challenge posed by other sports in the television age. Even as the tube brought fights into millions of homes, it hurt attendance at live events. Looking elsewhere for revenue, promoters began to stage most big fights at gambling casinos, a lucrative prospect for those in the money but one that separated the sport from a reliable fan base in major cities.

Yet the fact that TV proved a huge boon for most other sports suggests that we must look elsewhere for the true causes of boxing’s decline—above all, to changing tastes. In the long postwar boom, prosperity and higher living standards created different expectations for leisure and entertainment, as well as more refined attitudes. Boxing’s endemic corruption and scandal wore away its popular appeal and made the sport seem increasingly atavistic. Crooked managers and promoters; rankings of fighters doctored by fraudulent boxing organizations; allegations of fixed fights and bribed referees and judges; foul play in the ring, from illegal substances to doctored gloves; and fighters killed or maimed who shouldn’t have been fighting in the first place—these were among the reasons that the American public stopped taking the sport seriously.

Worst of all, though, were the sport’s effects on the human body. Boxing’s fatality rate is lower than that of horse racing and of some other sports, but its real scourge is not death but debility—particularly, brain damage. Today, the specter of brain trauma hovers over professional, college, and even high school football, posing a potential threat to that sport’s future. But awareness of boxing’s dangers long predates modern research. The image of the punch-drunk, shuffling old fighter goes back to the sport’s early days; researchers conducted studies of trauma in ex-fighters as early as the 1920s.

When the subject of boxing and brain trauma comes up today, the first image in everyone’s mind is that of Muhammad Ali, now 69. Afflicted with Parkinson’s disease, he moves hesitantly, is generally unintelligible, and shakes convulsively across his upper body; his moon-shaped face exhibits the masklike blankness so common to Parkinson’s—and Alzheimer’s—sufferers. Ali’s great ring model, Sugar Ray Robinson, who died in 1989, was afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease in his final years. Like Ali, Robinson fought long beyond the point at which he could protect himself. Boxing’s two most gifted and stylish performers, in their prime the antithesis of the brute fighter, ended up indistinguishable from the broken-down old pugs they were sure they’d never become.

In 1984, the American Medical Association, after years of study, called for a ban on boxing, citing the sport’s object of causing physical harm and the damage its participants clearly suffered to their mental faculties. Since then, other studies have continued to link boxing to severe brain trauma. But the AMA hasn’t been able to build enough momentum to ban boxing—ironically, because not enough people in the U.S. care one way or the other. Revulsion has passed into indifference.

Even as its popularity has ebbed, boxing flickers in the American consciousness. One surprising area in which the sport has made small inroads into American habits is the growth of “white-collar boxing,” in which men and women show up after their day jobs to spar or fight real bouts in a gym. Many health clubs now offer boxing-related fitness programs, as few activities can compete with boxing’s aerobic benefits. Boxing continues to fascinate great writers, as it always has—only baseball has a comparable literary pedigree. And the ring’s elemental sense of conflict has proved endlessly adaptable for filmmakers. The prominence of some recent boxing films, like Million Dollar Baby, Cinderella Man, and The Fighter, is impressive, considering that the many fine boxing films of the past—from Body and Soul, Champion, and The Set-Up to The Harder They Fall, Fat City, and Raging Bull—could count on broader public enthusiasm for the sport.

And just when one is tempted to turn forever from this sport of too much scandal and sorrow, someone emerges. In the past, boxing has endured other down periods before a galvanizing figure—Dempsey, Louis, Ali, Leonard—rescued it. If it is happening again, it’s thanks to the 32-year-old Filipino fighter Manny Pacquiao. He has won titles, or parts of titles, in eight weight divisions, which no one has ever done before. Some have dared say that he is among the greatest fighters in history.

What matters about Pacquiao is not just his record but who he is: a national hero in the Philippines and boxing’s most compelling star in many years. “Manny is our people’s idol and this generation’s shining light,” says former Philippine president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. “He is our David against Goliath, our hero and the bearer of the Filipino dream. . . . You can feel the excitement throughout the country every time he is in the ring.” Such devotion recalls the way fighters of the past were regarded by immigrant communities. Pacquiao seems to relish the burden he carries. Like some former champions, he harbors an epic concept of himself. Being a champion is not enough: he is an elected congressman from the Philippines’ Sarangani province, a job that, by all accounts, he takes seriously. He seems heartfelt in his desire to address the poverty of his native land and to stamp out sex trafficking, among other abuses. He also fancies himself a singer; after several of his recent fights, he has even given concerts.

Pacquiao is the kind of figure who could restore boxing to its former glory, if such a thing were possible. Boxing devotees yearn for him to participate in a “super fight” like those in which Sugar Ray Leonard fought in the 1980s. The opponent for such a battle is standing in plain sight: Floyd Mayweather, Jr., a brilliant defensive boxer who has never lost. But so far, no deal has been reached to get the two men to fight, and age is encroaching on both. Negotiations have broken down for various reasons, including Mayweather’s insistence that Pacquiao submit to drug testing shortly before the fight; some claim that Mayweather wants to avoid the contest altogether.

If the fight does happen, it would be the biggest boxing match in a generation. And though few believe it would work out this way, nothing would be more fitting than for such a battle to occur during a New York summer or early autumn, at Yankee Stadium, near the same spot where Dempsey, Louis, and Ali fought. At long last, America’s ghost sport would have reassembled the throngs—if only for a night.