Was the Enlightenment a Good Thing? At first blush, the question sounds almost sacrilegious. The eighteenth-century Enlightenment, after all, taught us to be democratic and to believe in human rights, tolerance, freedom of expression, and many other values that are still revered, if not always practiced, in modern societies. On the other hand, historians question whether the Enlightenment actually led to brotherhood and equality (it did not, of course), and even freedom, its third objective, was achieved only partially and late. Some have even suggested that its ideas of human “improvement” may have had unintended bad consequences such as twentieth-century totalitarianism, racism, and colonialism.

Yet the debate has obscured the most hardy and irreversible effect of the Enlightenment: it made us rich. It is by now a cliché to note how much better twenty-first-century people live than even the kings of three centuries back. In thousands of large and small things, material life today is immeasurably better than ever before. Are we happier? Who knows? Are we more enlightened? Possibly. But are we healthier and more comfortable? Of course we are. And without sounding too cocky about how progressive history is, or too triumphalist about Western culture as the crowning achievement of human development (a view that a majority of historians label “whiggish”), I would like to suggest that what generated all this prosperity was the growth of certain ideas in the century after the British Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Somehow this important connection has slipped past the scores of historians who have written about the rise of the modern world and variations on that theme. Most economic historians have focused not on intellectual but on economic factors, crediting resources, prices, investment, empire, or commerce with triggering the Industrial Revolution, which then led to the period of sustained economic growth in which we still find ourselves. Even though attributing economic change purely to economic causes at the exclusion of ideas is part and parcel of historical materialism, a theory generally associated with Marxism, free-market economists have frequently done the same thing, describing the effects of ideology as “a grin without a cat.” One of the few who dissented was John Maynard Keynes, who noted in a famous passage that “the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.” There is no better example than the Enlightenment ideas that, I submit, created the prosperity that we enjoy today.

The writers and thinkers whose work we call the Enlightenment were a motley crew of philosophers, scientists, mathematicians, physicians, and other intellectuals. They differed on many topics, but most of them agreed that improvement of the human condition was both possible and desirable. This sounds trite to us, but it is worth pointing out that in 1700, few people on this planet had much reason to believe that their lives would ever get better. For most, life was not much less short, brutish, and nasty than it had been 1,000 years earlier. The vicious religious wars that Europe had suffered for many decades had not improved things, and though there had been a few advances—the wider availability of books, for instance, and a trickle of new goods from overseas, such as tea and sugar—their impact on the overall quality of life remained marginal. An average Briton born in 1700 could expect to live about 35 years, spending his days doing hard physical work and his nights in a cold, crowded, vermin-ridden home.

Against this grim backdrop, Enlightenment philosophers developed a belief in the capability of what they called “useful knowledge” to advance the state of humanity. The most influential proponent of this belief was the earlier English philosopher Francis Bacon, who had emphasized that knowledge of the physical environment was the key to material progress: “We cannot command Nature except by obeying her,” he wrote in 1620 in his New Organon. The agenda of what we would call “research and development” began to expand from the researcher’s interest alone—or his desire to illustrate the Creator’s wisdom—to include the hope that one day his knowledge could be put to good use. In 1671, one of the most eminent scientists of the age, Robert Boyle, wrote that “there is scarce any considerable physical truth, which is not, as it were, teeming with profitable inventions, and may not by human skill and industry, be made the fruitful mother of divers things useful.” The idea spread to other nations. The great French scientist René Réaumur, a mathematician by training, spent much of his career researching such mundane matters as steel, paper, and insects in the hope of using this knowledge in industry and agriculture.

To bring about the progress that they envisioned—to solve pragmatic problems of industry, agriculture, medicine, and navigation—European scientists realized that they needed to accumulate a solid body of knowledge and that this required, above all, reliable communications. They churned out encyclopedias, compendiums, dictionaries, and technical volumes—the search engines of their day—in which useful knowledge was organized, cataloged, classified, and made as available as possible. One of these tomes was Diderot’s Encyclopédie, perhaps the Enlightenment document par excellence. The age of Enlightenment was also the age of the “Republic of Science,” a transnational, informal community in which European scientists relied on an epistolary network to read, critique, translate, and sometimes plagiarize one another’s ideas and work. Nationality mattered little, it seemed, compared with the shared goal of human progress. “The sciences,” said the great chemist Antoine Lavoisier, “are never at war.” Like many of the lofty ideals of the eighteenth century, this notion eventually proved, to some extent, illusory.

Yet the idea of material progress through the expansion of useful knowledge—what historians today call the Baconian program—slowly took root. The Royal Society, founded in London in 1660, was explicitly based on Bacon’s ideas. Its purpose, it claimed, was “to improve the knowledge of naturall things, and all useful Arts, Manufactures, Mechanick practises, Engines, and Inventions by Experiments.” But the movement experienced a veritable spurt during the eighteenth century, when private organizations were established throughout Britain to build bridges between those who knew things and those who made things. One example was the oddly named Lunar Society of Birmingham, in which leading scientists met regularly with famed entrepreneurs, including the greatest engineer of his age, James Watt, and his partner Matthew Boulton. Another was the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, whose members included many of the most prominent businessmen in Britain’s rapidly growing cotton industry.

More and more manufacturers sought the advice of scientists and mathematicians to solve technical bottlenecks and enhance productivity. The record of those consultants was mixed; more often than not, a consultant told a firm something that it already knew or something that it could have found out less expensively. But what is interesting is how widespread the belief that science could help industry had become by 1780.

The Baconian program proved unusually successful in Britain, and hence it led the world in industrial innovation. There were many reasons for this, not the least of them England’s union with Scotland in 1707. The historian Arthur Herman has written, with some exaggeration, that the Scots invented the modern world. The Universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow were the Scottish Enlightenment’s versions of Harvard and MIT: rivals up to a point, but cooperating in generating the useful knowledge underlying new technology. They employed some of the greatest minds of the time—above all, Adam Smith. The philosopher David Hume, a friend of Smith’s, was twice denied a tenured professorship on account of his heterodox beliefs. In an earlier age, he might have been in trouble with the law; but in enlightened Scotland, he lived a peaceful life as a librarian and civil servant. Another Scot and friend of Smith’s, Adam Ferguson, introduced the concept of civil society. Scotland did not just produce philosophers, either; it also exported to England many of its most talented engineers and chemists, above all James Watt.

It is absurd to argue, as some scholars have, that England had no Enlightenment of its own. But the English Enlightenment was more practical than the Scottish, and perhaps that was what was needed for innovation. Consider Josiah Wedgwood, the great Staffordshire potter who single-handedly revolutionized an entire industry. Wedgwood was a typical Enlightenment figure: opposed to slavery, closely connected with the most prominent intellectuals of his age, and continuously studying science, consulting with scientists, and improving his technology and marketing. Wedgwood’s celebrated invention of jasperware—a kind of stoneware colored by adding selected metal oxides—has been called the most significant innovation in ceramic history since the Chinese invention of porcelain. It came after thousands of experiments in Wedgwood’s Staffordshire laboratories. Clearly, progress in this area was no longer confined to the random stumblings of inspired artisans.

In a few areas, useful knowledge turned out to be hugely productive. The rapidly growing cotton industry needed a chemical agent that could bleach fabrics, but traditional techniques were slow and expensive. In 1774, a Swedish chemist, Carl Wilhelm Scheele, discovered a substance that the Frenchman Claude Berthollet subsequently realized had miraculous bleaching properties. The recognition that this substance, later called chlorine, had industrial potential was a British idea. (Its other properties were discovered later: it began to be used as a disinfectant in the mid-nineteenth century, and the widespread chlorination of water began in the twentieth.)

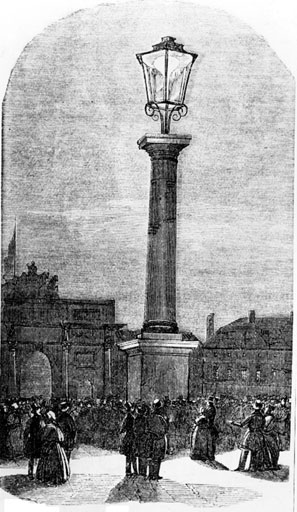

Another example of the success of the Baconian program was in the field of lighting. Candles were expensive, emitted smoke, and often caused fires. Scientists all over enlightened Europe began to put their minds to the problem. In about 1780, Archibald Cochrane, the brilliant but eccentric earl of Dundonald, lit the coal gas above his tar ovens, mostly to amuse his friends; but we are not sure who first realized that the gas could not only burn well but also produce an immensely useful service. Claims for the breakthrough have been made for Jean-Pierre Minkelers, reputed to have lit his Leuven classroom with gas in 1784, and for Johann Georg Pickel, who certainly lit his German laboratory with gas in 1786. In 1799, the Frenchman Philippe Lebon took out a patent for a “thermolamp,” a glass device that would burn a combination of air and gas distilled from wood. After Lebon conducted a number of well-publicized demonstrations in Paris in 1801, it became abundantly clear that a radical new possibility had opened up. In 1807, some of Manchester’s cotton mills and the entire length of London’s Pall Mall were illuminated by coal gas in honor of King George’s birthday. In the following decade, gaslight turned night into day for many Europeans.

Optimism continued to abound about the potential of useful knowledge to improve the world. In 1780, one of the greatest figures of the Enlightenment, Benjamin Franklin, wrote in a letter that “the rapid progress true Science now makes, occasions my regretting sometimes that I was born so soon. It is impossible to imagine the Height to which may be carried, in a thousand years, the Power of Man over Matter. . . . O, that Moral Science were in as fair a way of Improvement.” He addressed that very Baconian sentiment to his friend Joseph Priestley, the British scientist and philosopher who invented soda water and discovered oxygen.

The age of Enlightenment, of course, was also the age of Newton, whose discoveries made it possible to understand the movement of heavenly bodies. This was widely regarded as a hint of things to come: if we can understand this, we can understand anything. But nature turned out to be messier than expected. For a century, many areas of research resisted efforts at improvement simply because the underlying physics and chemistry, not to mention biology, had not advanced enough. A good example is the slow development of electrical power. Eighteenth-century science was fascinated by electricity and sensed its potential; in 1760, the preface to Franklin’s New Experiments and Observations on Electricity stated prophetically that electricity was perhaps the most formidable and irresistible agent in the universe. Yet it was to take another century and the work of many scientists until electrical power could become economically useful.

Advances in medicine proved similarly sporadic. Enlightened physicians were passionate about progress. How could they not be? Twenty out of every 100 babies perished in their first year; many young and talented women and men died prematurely of dreaded disease; adult life was often a sequence of disfiguring and debilitating sicknesses. “I see no reason to doubt that, by taking advantage of various and continual accessions as they accrue to science, the same power will be acquired over living, as it is at present exercised over some inanimate bodies,” wrote Thomas Beddoes, a learned English medic, in 1793. And there was at least one major success story in his lifetime: Edward Jenner’s discovery of the smallpox vaccine three years later. One could mention a few more modest advances, such as the discovery that citrus fruit could protect sailors against scurvy. But these discoveries were exceptional: useful knowledge could not control, much less cure, most diseases before 1850. Moreover, new diseases appeared that left the profession helpless: cholera was to the 1830s what HIV was to the 1980s, and it took decades even to isolate its mode of transmission. Beddoes died a disappointed and disillusioned man.

Even in industry, the immediate effect of the Baconian program was limited. Some of the most important inventions of the eighteenth century, especially in textiles, were ingenious mechanical contraptions but did not depend on advances in physics. Hargreaves’s spinning jenny and Whitney’s cotton gin, to name just two, included no elements that Archimedes could not have understood. The novelty in the eighteenth century was to realize how much science and technology could learn from each other. But innovation still owed less to formal science than to the intuition, ingenuity, and dexterity of mechanical geniuses like Watt, who did more than most to make the steam engine efficient but did not fully understand the physics of steam power. It was not until 1824, five years after Watt’s death, that the French scientist Nicolas Sadi Carnot, intrigued by the steam engine, wrote an essay that laid the foundation for modern thermodynamics.

Yet the employment of the Baconian program turned out to be a critical juncture in human history. Without it, innovation might well have fizzled out. It is easy to imagine a very different historical scenario, one in which technology advanced just far enough to create a world of mechanical cotton-spinning and cheaper bar iron—and then stagnated. Previous technological efflorescences, such as the fifteenth century’s invention of printing, ocean-worthy ships, and firearms, had crystallized in just that way.

But the nineteenth century was different, thanks to the intellectual revolutions of the previous century. After 1815, the spirit of improvement picked up steam, so to speak, and the world would never be the same. Even though the Enlightenment, properly speaking, was long past, its legacy was the great nineteenth-century technological breakthroughs: cheap steel, the germ theory of disease, the taming of electricity, the inventions derived from thermodynamics and organic chemistry, and many others. In 1787, Immanuel Kant famously wrote that he lived in an age of enlightenment but not in an enlightened age. The nineteenth century was just the opposite: no longer the age of Enlightenment but an enlightened age, in the admittedly narrow sense that it was hell-bent on carrying out the Baconian program.

The Enlightenment’s contributions to long-term economic growth were not merely scientific, moreover. Many economists, following the leadership of Nobel laureate Douglass North, have begun to see Enlightenment economic and political ideas as central to the process. Early economic doctrine, often called mercantilism, taught that trade was a zero-sum game: if one side gained, the other lost. Such thinking led to policies that today we call “protectionist,” and every economics teacher in the country revels in teaching that they are inefficient and costly. The idea that trade normally benefits both sides led to the growth of free trade after 1815 and was central to the establishment of free-trade areas in Europe and elsewhere after 1950. That understanding grew out of the Enlightenment and the thinking of such intellectual giants as Smith and Hume.

Even more important was the Enlightenment notion of freedom of expression. In our age, we think of technological change as natural and obvious; indeed, we consider its absence a source of concern. Not so in the past: inventors were seen as disrespectful, rebelling against the existing order, threatening the stability of the regime and the Church, and jeopardizing employment. In the eighteenth century, this notion slowly began to give way to tolerance, to the belief that those with odd notions should be allowed to subject them to a market test. Many novel ideas were experimented with, especially in medicine, in which new ways to fight disease were constantly being proposed and tried (often on unsuspecting patients serving as guinea pigs). Words like “heretic” to describe innovators began to disappear. Indeed, some of the towering figures of the Industrial Revolution—above all, Watt and Jenner—became international celebrities.

Critics of the Enlightenment are surely right that it did not turn Europeans into choirboys. The French Revolution, initially inspired by Enlightenment thought, degenerated into a murderous bloodbath and then into a military dictatorship. The two most enlightened nations, France and Britain, turned on each other in 1793 in a vicious war that lasted more than 20 years and led to oppressive, unenlightened domestic policies. The American Revolution, just as much a child of the Enlightenment as the French, tolerated and codified slavery. In the nineteenth century, Europeans used their new technology to oppress, exploit, and murder non-Europeans; in the late nineteenth century, they replaced the transnational ideals of some enlightened thinkers with an often ugly nationalism that taught the masses that the way to show love for their country was to hate its neighbors; and in the first half of the twentieth century, they turned on one another with a brutality and destructiveness that history had never witnessed before.

So the Enlightenment, sadly, did not end barbarism and violence. But it did end poverty in much of the world that embraced it. Once the dust settled after the upheavals and violence of the French Revolution, Europe entered a century of economic growth (known as the pax Britannica) punctuated by a few relatively short and local wars. By 1914, countries that had experienced some kind of Enlightenment had become rich and industrialized, while those that had not, or that had resisted it successfully (such as Spain and Russia), remained behind. The “club” of rich countries formed the core of the industrialized world for most of the twentieth century. Even after two massive wars whose devastation would have sent any ancient empire down the road to ruin, Europe bounced back, and today the quality of life there is the envy of much of the rest of humanity.

As unlikely as it may seem, then, a fairly small community of intellectuals in a small corner of eighteenth-century Europe changed world history. Not only did they agree on the desirability of progress; they wrote a detailed program of how to implement it and then, astoundingly, carried it through. Today, we enjoy material comforts, access to information and entertainment, better health, seeing practically all our children reach adulthood (even if we elect to have fewer of them), and a reasonable expectation of many years in leisurely and economically secure retirement. These are luxuries that Smith, Hume, Watt, and Wedgwood could only dream of. But without the Enlightenment, they would not have happened.

Technological progress has become part of our lives. We have learned to expect that science and technology will advance every year and that we will discover more and more about the physical world in order to improve our material existence, whether in medicine, materials, energy, or information technology. Our growing concern with the environment and the influence that technology has had on our fragile planet is adding nuance and sophistication to this belief. The age of Enlightenment burned coal without concern, unaware of the impact of hydrocarbons on the atmosphere. Our age is learning a further lesson: we need technological progress more than ever, but we need to be smart about it. Ben Franklin would agree.