The immediate post–Great Recession years were dark times for the Republican Party in Connecticut. Democrats ran up commanding majorities in the state House and Senate in the November 2008 elections, and two years later, Dannel Malloy’s election gave Democrats control of the state’s executive branch for the first time in two decades. In 2010 and 2012, Republican Linda McMahon spent almost $100 million of her personal fortune in campaigns for the U.S. Senate but lost both races by double digits.

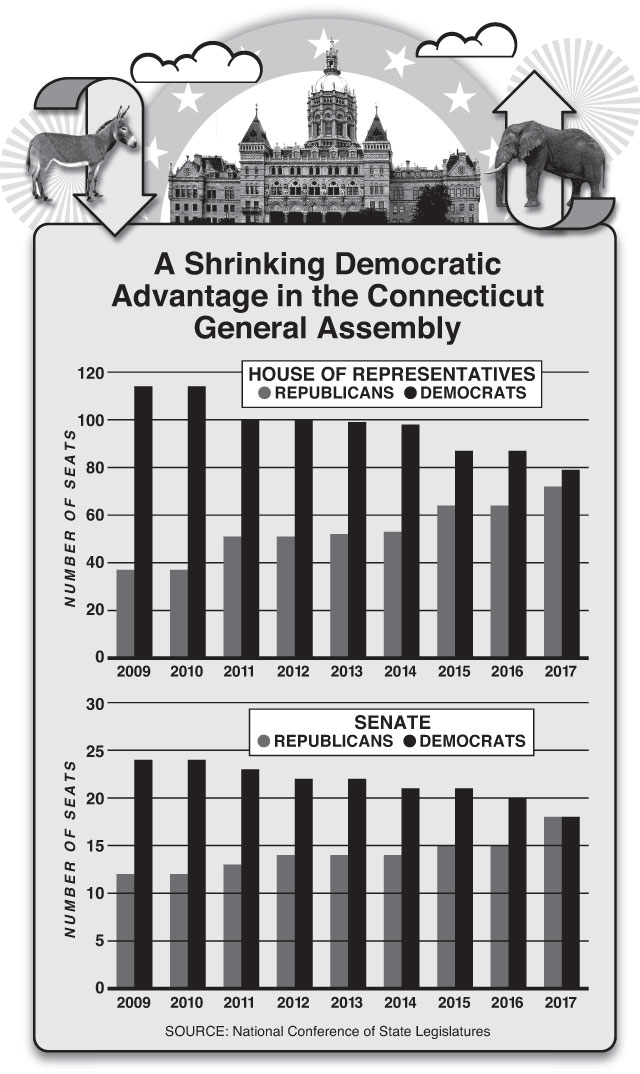

The Left’s hold on Connecticut now looks more fragile. In November 2016, Republicans tied the state Senate and trimmed Democrats’ majority in the House to just seven seats, down from a 77-seat margin eight years ago. Since Connecticut’s entire congressional delegation in Washington is Democratic and counts some leading members of the progressive “resistance” to President Trump—such as Representative Rosa DeLauro and Senators Richard Blumenthal and Chris Murphy—Republicans’ recent winning streak in state politics can’t be chalked up to any “coattails” effect relating to national trends. Having watched his approval rating plummet—he’s the nation’s most unpopular Democratic governor, according to the Morning Consult—Malloy announced in April 2017 that he would not seek a third term in 2018. Connecticut remains deep-blue in national politics; it hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1988, and Hillary Clinton won the state comfortably. Yet even as some blue states have lurched further left in the age of Trump, Connecticut has been moving in the opposite direction.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Connecticut Democrats’ recent losing streak is the result of widespread dissatisfaction with the state’s fiscal and economic model. Budget deficits recur, despite three major tax hikes since 2009. A high legacy-cost burden makes further tax increases seem almost inevitable. Coming out of the Great Recession, Connecticut’s economy has endured painfully slow rates of growth, a trend highlighted by General Electric recently relocating outside the state. Connecticut’s credit rating from Moody’s is lower than that of any state except New Jersey and Illinois. It’s not inconceivable that Republicans could gain control of the governorship and both houses of the legislature this November.

In the American system of government, states are often called the “laboratories of democracy”—the testing grounds for new ideas and policies that, if successful, reward their practitioners with political advancement. In truth, politicians at the state and local levels are frequently reelected even after running a jurisdiction into the ground with disastrous policies (see, for instance, Detroit). In Connecticut, though, the laboratory metaphor may prove out: with the progressive fiscal model collapsing, state officials have no choice but to hunt for an alternative.

With one out of every two of its jobs in manufacturing, Connecticut was the nation’s most industrialized state during the post–World War II era. Manufacturing work was both abundant and well compensated: during its peak industrial era, Connecticut ranked at or near the top among all states in per-capita income. Between 1950 and 1970, the state’s population swelled by 50 percent, a growth rate roughly equivalent to what Arizona and Nevada have experienced in the twenty-first century.

As recently as the early 1990s, manufacturing remained “the State’s single most important economic activity,” according to the governor’s annual economic report. Around that time, though, finance began its ascent and would eventually claim the title of Connecticut’s indispensable industry, at least as measured by output and income. (In terms of employment, no industry in Connecticut dominates as manufacturing once did.) A 2016 report by the financial-research firm Preqin found that Connecticut’s hedge-fund industry, measured by assets under management, ranked second among all states, outpacing even California. Though its economy has changed composition dramatically, Connecticut is still one of the highest-income states—indeed, its per-capita income leads the U.S., and its poverty rate is fourth-lowest among all states.

Conservative fiscal policy, coupled with the missteps of rival states, helped bolster the Connecticut economy throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. New York State’s top income-tax rate surged into the double-digits around 1960, and an extra city-level tax was imposed in 1966. New York’s combined top state and city gross income-tax rate reached a peak of 19.7 percent in 1976. By contrast, Connecticut’s gross income-tax rate was zero, and would remain so until the early 1990s. During New York’s fiscal crisis, debates about the city’s future often invoked fears of residents and businesses fleeing to Connecticut, where taxes were lower and services widely considered superior.

After World War II, major cities such as Hartford, Bridgeport, New Haven, and Waterbury powered the Connecticut economy. Since 1960, however, all these areas have faced a downward spiral of industrial decline, worsening poverty, and excessive debt and retirement-benefit commitments. Both Bridgeport and Waterbury have had brushes with insolvency in recent decades, but at present, Hartford is the worst-off. (See box, below.) Hartford managed to escape bankruptcy only through an eleventh-hour bailout provided by state government in October 2017. Connecticut’s commercial center is now located in suburban Fairfield County, the “panhandle” of the state that borders New York’s Westchester County. Fairfield developed as a network of bedroom communities servicing New York City, and, in many ways, it has retained this identity. According to the census, 32,000 Fairfield residents commute to New York. But Fairfield is also host to many important companies in its own right—most notably, in the hedge-fund industry.

Hartford Descending

Once affluent, Connecticut’s capital city, Hartford, is now one of the poorest and most fiscally distressed cities in the United States. In 1960, Hartford’s median family income of $5,990 was 6 percent higher than that of the nation as a whole. These days, median family income stands at about half the national average. Steady erosion of the city’s tax base has coincided with an unsustainable expansion in its retirement-benefit and debt burdens, which collectively total over $1 billion.

In early 2017, city officials resolved that neither further service cuts nor tax increases were feasible and that only a state bailout could save Hartford from bankruptcy—but only if the legislature could settle on a budget for the coming fiscal year. Throughout their nine-month deliberations over how to close Connecticut’s multibillion-dollar deficit, state officials sent mixed signals about rescuing Hartford. Last spring, state senate Republican leader Len Fasano called the $40 million that Hartford was seeking “manageable” and emphasized that “Hartford filing bankruptcy is not a good headline for the state.” But a budget that Republicans crafted and passed in September was so parsimonious in the aid it offered that, according to Hartford mayor Luke Bronin, the city would have had to file for bankruptcy under its terms, had it not been vetoed by Connecticut governor Dannel Malloy. When the state finally adopted a budget in October, it met the city’s request for financial assistance in full. The only condition: Hartford would have to submit to some state oversight.

Hartford’s credit remains junk-rated, and the city projects sizable deficits in the near term. State officials have not heard the last demand for increased municipal aid, especially since other Connecticut cities, such as New Haven and Bridgeport, are also under fiscal strain. What these cities want is more no-strings-attached general treasury support. But that’s a tough ask, given the numerous other claims now placed on state resources for retirement benefits, debt service, safety-net programs, and so on. (Connecticut did itself no favors by declining to impose a stricter oversight regime in Hartford, which could have prompted mayors elsewhere to think twice about whether a bailout is worth the price of giving up power.)

What does Connecticut owe its cities? Municipal aid, which includes funds for K–12 public education, already represents a $5 billion obligation and will account for one-quarter of the state budget by 2020. City residents have a right to expect adequate municipal services. Thus, the state arguably should intervene in instances of potential municipal insolvency—but that’s a different standard, and commitment, from full-on revitalization for Hartford, Bridgeport, and New Haven, a feat that state government could not guarantee even if it tried.

In most discussions of how Connecticut lost its way, 1991 looms large. That year, state lawmakers voted to institute an income tax. Though the topic remained controversial throughout the postwar years, and Connecticut did impose a tax on investment earnings that reached as high as 14 percent in the late 1980s, state officials had avoided taxing wages and salaries for far longer than most states. What finally tipped the scales was a budget crisis following the 1990 recession, coupled with the insistence of Governor Lowell Weicker. Representing Connecticut in the U.S. Senate throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Weicker was a Republican in the Rockefeller mold: a social liberal with a reputation for fiscal responsibility that masked his devotion to big government. After losing reelection in 1988 to Democrat Joseph Lieberman, who ran to his right, Weicker became an independent. In 1990, he ran for governor and narrowly won in a three-way race. During that campaign, it became clear that the winner would face tough budgetary decisions. Weicker’s opponents charged that his equivocation on whether new revenues would be necessary (“everything is on the table”) meant that he favored an income tax. Under pressure to respond, Weicker released an ad contending that raising income taxes at that time would be like “pouring gasoline on the fires of recession. And nobody’s for that.” This reassurance was enough to put Weicker over the top. Almost as soon as he entered office, though, he released a budget proposal calling for an income tax to address the state deficit. Against fierce opposition, Weicker pushed the tax through the legislature.

For his income-tax advocacy, Weicker was lionized by liberals such as the New York Times editorial board and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, which gave him a Profile in Courage award. But many voters felt misled. “Hang the lying bastard!” read signs seen during a legendary antitax rally in October 1991. Connecticut has never been known for a raucous political culture. That about 40,000 people gathered that day at the Capitol to vent their anger suggests that the adoption of the income tax was a watershed in state history.

Weicker linked the income tax with other changes and sold the package as a tax reform that would make the state more business-friendly. The state’s tax on investment income was effectively slashed, as capital gains, interest, and dividends got folded into gross income, all of which was taxed at the same rate. This did energize the financial sector. Between the early 1990s tax reform and the Great Recession, employment in the securities industry tripled in Connecticut—a rate of growth that significantly beat that of New York, New Jersey, and the nation as a whole. Of course, as financial analyst Adam Stern explains in a lengthy account of Connecticut’s tax wars published in Connecticut History, “middle class and upper-middle class taxpayers were hit hardest” by the new levy, because their resources were more concentrated in “ordinary income” and less in capital gains and dividends—as the cohort protesting at the Capitol understood. Shifting the tax burden from investment to ordinary income was supposed to reduce volatility in government revenues, but, over time, state officials have diluted that benefit with each new income-tax hike (the top rate is now 6.99 percent, up from the original 4.5 percent). Investment income is certainly more volatile than ordinary income. But the old investment income tax never provided more than 10 percent of revenues, whereas the broad-based income tax now supports over half the state budget. And the notion that taxing wages and salaries could keep other taxes under control has not been borne out in the case of the property tax (only New Jersey has higher property taxes than Connecticut) or the sales tax, which legislators have increased in an effort to balance the budget.

It’s ironic that Weicker established his reputation as a “maverick” (the title of his 1995 autobiography) by making Connecticut’s tax system like almost all other states’. (Forty-one had already adopted an income tax by the time Connecticut did.) Pre-Weicker, Connecticut’s revenue structure may not have been perfect, but anxiety over the state’s competitiveness runs much deeper now than it did in the late 1980s.

The new tax yielded the expected revenues—$126 billion through 2014, according to the Yankee Institute, a Hartford-based think tank—but the windfall was not responsibly managed. Particularly egregious was lawmakers’ neglect of the state pension system. Though revenues from the new tax generated a surplus soon after its adoption, officials skimped on pension contributions, causing the pension fund to miss out on the dot-com stock-market boom. Now, the pension plans are underfunded by $27.5 billion, and Connecticut ranks fourth-worst in the most recent Pew survey of pension underfunding among states. State officials have resorted to gimmicks to keep pension spending from overwhelming the budget. Early in 2017, officials passed a plan to push at least $14 billion in pension contributions onto the next generation of taxpayers for the state-employee system. And in 2009, the state issued $2.3 billion in pension-obligation bonds to prop up the teachers’ system, but costs have continued to spike. Prevented by the bond covenant from restructuring the teacher-pension contribution, Governor Malloy recently proposed pushing one-third of the annual tab onto cities and towns. The legislature has nixed that idea for now, but regardless of who ends up with the bill, Connecticut has few good options: about 80 percent of the state’s annual pension contribution is for benefits already earned, so reducing current workers’ pensions will not have much impact. Anyone familiar with state and local finance will find the story unsurprising: when Connecticut had the money to fund its pension system, it failed to make adequate contributions. Now that it doesn’t have the money, the costs of fully funding the system are insupportable.

Pensions are not the only source of strain on the state budget. Connecticut also owes $21.9 billion in unfunded retiree health-care liabilities. In 2016, a Pew Charitable Trusts study found that, measured as a share of personal income, Connecticut’s bonded-debt burden was the third-highest among all states. Tension between the costs of the past and the needs of the present has intensified as a result of an underperforming state economy. Connecticut did not recover all the private-sector jobs that it lost during the Great Recession until June 2017. It has been one of the four slowest-growing states in recent years. Rates of income and GDP growth have trailed competitor states Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey, as well as the nation as a whole. With a relatively old population, a low birthrate, and net outmigration, Connecticut has lost population in each of the last three years.

In 2015, with state lawmakers poised to enact the third major tax increase since 2009, Fairfield-based General Electric warned that higher taxes “makes businesses, including our own, and citizens seriously consider whether it makes any sense to continue to be located in this state.” It wasn’t bluffing. In January 2016, GE announced that it would move to Boston.

The 2017 budget debate brought to a head the debate over the state’s fiscal future. Connecticut failed to settle on a balanced budget until four months after the end of the last fiscal year—longer than any other state. Estimates for the two-year shortfall reached as high as $5.1 billion. A midyear deficit also opened up, caused by underperforming tax receipts. These were frustrating developments in light of the three rounds of tax hikes since 2009. While the most noticeable changes have affected high earners, Connecticut’s insatiable revenue needs have caused policymakers to raise income taxes on individuals making as little as $50,000 and to increase the sales tax. Reserves have been almost completely drained. Chastened by years of bad news about the state economy, Malloy and mainstream Democrats refused to consider another income-tax hike. Ben Barnes, the Malloy administration’s influential budget chief, told the Connecticut Mirror, “We became this Mecca for affluent people and well-educated people . . . partly because we were a tax haven. . . . People came to Greenwich because it was cheaper than living in New York or in Rye, and we may have lost some of that. It’s hard to argue that that didn’t serve us very well, and I’m a liberal Democrat. . . . The goose might not stick around and continue laying golden eggs if we don’t give it a nice, hospitable place to be.”

Connecticut could serve as Exhibit A for the risks involved in trying to run a progressive tax system in an era of high and rising “fixed” costs (entitlements, retirement-benefit costs, and debt service). With each new income-tax hike, the state budget has become more dependent on a smaller number of extremely high earners. In 2015, Connecticut income-tax filers reporting over $1 million in earnings represented less than 1 percent of all filers—but 30 percent of total taxes owed. According to the state’s Office of Fiscal Analysis, revenue growth in FY15 was “relatively flat . . . in large part” because the top 50 taxpayers earned $3 billion less than they did the year before. Theoretically, state finance officials could spread the loss of a few million in revenues across the budget without much impact, but Connecticut’s fixed-cost albatross means that each new round of cuts must be concentrated in slimmer portions of the state budget. The Office of Fiscal Analysis has shown that fixed costs now consume 53 percent of the state budget. More spending on fixed costs means less flexibility to respond to revenue declines and less spending on “non-fixed” costs, such as higher education and grants to cities and towns.

Many Connecticut Democrats now understand the need for structural change, and they will need to work together with conservatives and centrists to bring it about. To secure a better future for Connecticut, Democrats and Republicans alike must adhere to three general principles: ignore the urban advocates, hold the line on taxes, and rein in government unions.

Some progressives have tried to change the subject from the failed fiscal model by arguing that the real problem is that Connecticut is too suburban and lacks vital urban centers, a thesis gaining traction in liberal media outlets such as Slate and The Atlantic. They’re wrong. Connecticut’s small cities (none have a population larger than 200,000) resemble Rust Belt cities: they reached a peak of population and economic vitality during the postwar era that has irrevocably passed, despite policymakers’ efforts at revival. Beyond Connecticut, most small Rust Belt cities haven’t come back, either. In revitalizing Connecticut’s cities, policymakers should look to places like Erie, Lowell, and Worcester—fiscally stable, well-managed cities, none with any hope of landing a General Electric. New York and Boston are not useful models for Bridgeport, New Haven, Hartford, and Waterbury. The number of millennials—Americans born between 1981 and 2000, many with a preference for urban living—will begin to plateau in the next decade, and cities will find themselves in a zero-sum competition for young educated professionals. If Connecticut’s future really depends on its cities’ gaining millennial market share from New York and Boston, grim days lie ahead.

Accounts of the looming collapse of suburban America are just as misleading. Cheaply built, inner-ring suburban regions that sprang up near central cities after the war are poised for a fall, as growth passes them by in favor of exurban areas. But Connecticut’s suburbs are generally former rural New England townships that have been around for centuries. Founded long before the automobile, their design bears more of a resemblance to a city than does, say, Levittown or an Arizona subdivision. They offer handsome old housing stock and excellent public schools, features that many millennials will value as they settle into middle age, just as prior generations did. (Not even successful cities like New York and Boston have succeeded in bringing back middle-class families.)

Over the medium term—the appropriate horizon for policymakers to consider—Connecticut will need to rely far more on its suburbs—Fairfield County, in particular—than on its cities. As the state’s most populous and affluent county, Fairfield is essential to Connecticut’s success. Its residents pay 43 percent of all full-time residents’ state income taxes. Over the last two decades, the state’s dependence on the income tax, and the income tax’s concentration in suburban Fairfield, have grown. Shifting focus away from the suburbs when the state government has, for two decades, increased its dependence on them makes no sense. Tiny New Canaan (population 20,000) throws off more income-tax revenues than New Haven, Waterbury, and Hartford combined.

Shoring up Connecticut’s essential county—and indirectly, the state budget—will require keeping a close eye on Fairfield’s competitiveness with its historical foe, Westchester County. According to the most recent census data, Fairfield’s median home value is down 16 percent from ten years ago—suggesting a much slower recovery from the housing-market collapse than Westchester, Long Island, and many affluent New Jersey counties have experienced. But lower home values may serve as a competitive advantage; property-tax trends will not. Though property taxes remain lower in Fairfield than in Westchester, the gap has narrowed in recent years.

With a legacy-cost burden of close to $75 billion, Connecticut will find it hard to cut taxes anytime soon. The only two states that Moody’s rates lower than Connecticut—New Jersey and Illinois—have been punished in the bond market for trying to bring down taxes without also paring back their unsustainable long-term financial obligations. But Connecticut at least needs to hold the line on new taxes. As noted above, the bad old days of New York City were good for Connecticut. The city’s revival has been of more ambiguous benefit since New York has become as much a competitor with Connecticut as a regional ally. Connecticut suffers from a perception that, though New York City may be a high-tax jurisdiction, you get something back for your money; in Connecticut, each new tax just goes to cover the costs of the past. This perception is flawed—taxes in New York could be much lower were it not for its own legacy-cost burden—but influential.

“With a legacy-cost burden of close to $75 billion, Connecticut will find it hard to cut taxes anytime soon.”

One early test of Connecticut politicians’ acknowledgment of the need for a new fiscal direction came during negotiations with the State Employee Bargaining Agent Coalition (SEBAC), during the 2017 budget process. Looking to secure $1.5 billion in savings over two years, the state had to sign off on extending the current union contract for another decade. To many Connecticut conservatives, such as Carol Platt Liebau, president of the Yankee Institute, the SEBAC deal indicated more business as usual: “Right now we haven’t seen a bipartisan commitment to standing up to this dominant special interest in the government union,” she said. “And until you either see a party in charge that is willing to do that or a bipartisan commitment to doing it, it’s very hard to give people confidence that these systemic issues are going to be handled.” If Connecticut wants to signal its repudiation of failed fiscal policies, no longer making bad union deals would be a good place to start. (The current state House speaker, Joe Aresimowicz, is an AFSCME employee.)

As much as is politically feasible, the state should push to replicate Wisconsin governor Scott Walker’s 2011 “Act 10” reforms. Act 10 essentially ended collective bargaining for nearly all compensation and employment-condition matters for most government workers in Wisconsin. What’s in the public interest is not always what’s in the union interest. Post–Act 10, Wisconsin officials can pursue a less qualified notion of the public interest in their budgeting practices. State and local managers in Connecticut need more leverage at the bargaining table if they have any hope of containing personnel costs. Providing them with that leverage will require new legislation.

For all its faults, Connecticut remains an attractive place to live and to do business. The workforce, one of America’s best educated and most productive, is an asset for potential employers and should provide adaptability as Connecticut grapples with economic change. Connecticut’s high incomes and low poverty levels provide a strong foundation capable of supporting the cost of government. Rejuvenating the state economy will be difficult, but Connecticut finds itself in direct competition with mostly other blue states shouldering similar legacy-cost burdens—and Democrats in those states, especially New York and New Jersey, seem unconcerned about the hazards of unchecked progressivism. Thus, Connecticut doesn’t have to be perfect. It just needs to stop making unforced errors—and then wait for its rivals to blow it.

Top Photo: Anger over Connecticut’s profligate ways has been escalating since the state instituted an income tax in the 1990s. (SVEN MARTSON/THE IMAGE WORKS)