In Paris, the mid-October sky is overcast and a cool breeze announces autumn. I know this only because I’ve checked the weather report on my smartphone, as I do every morning when I’m in New York, where I now live part of the year. In France, I don’t bother to check the New York weather. There’s no point, since, swept as it is by marine winds, the city sees its temperature fluctuate from one hour to the next. It’s 9 AM in Gotham, and, at least for now, it’s sunny and warm, an Indian summer day.

To enter the jury room in the courthouse named after former senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, one must go through a fastidious security check, as is the case with all New York public buildings since the 9/11 terrorist attacks. In fact, the courthouse is just down the street from where the Twin Towers stood before their destruction, and where the Freedom Tower, an architectural improvement, rises today. I remove my jacket and belt, empty my pockets, and hand over my mobile phone to a security guard. This morning, in this building, I will add to my French nationality a new, supplementary identity: I will become an American citizen.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Citizenship is the key term. I will enter into a moral contract with the Constitution of the United States, while in no way denying my French culture, my Jewish heritage, or my classical liberal commitments; indeed, as authorized by both American and French law, I can also retain my French citizenship as a new American. The upcoming ceremony represents the culmination of a long process, initiated by my father in 1933, when he fled Poland, seeking to escape the Nazis. He wanted to immigrate to the U.S. but only got as far as France.

Finally, a bit weary after the wait to get through security, I reach the jury room and find a place on a bench at the back, behind a massive marble column, which obstructs my view of the American flag to which I will be required to pledge an oath of allegiance. (The United States was the first nation to legislate a right to naturalization, as was consistent with the universalizing vocation of its Constitution.) Soon, I’m reciting the oath, repeating word for word the text that the judge first reads to us: “I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty.”

My 300 or so fellow new citizens for the most part seem to speak little English, but they, too, repeat diligently the terms, which date from 1790, doubtless without fully understanding what they’re saying. All the participants, I’m sure, do understand that this collective recitation—a patriotic rite of initiation—transports us from darkness into light. In the words of the oath, we cease to be subjects of foreign powers in order henceforth to “support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States. . . . So help me God.” As a secular European, I wonder to myself: What is God doing in this ceremony? It’s an American God, though, generic to the point that anyone in the room, even an atheist, can accept His role—an ecumenical God for all occasions.

In this multicolored assembly, representing all the continents, I am a rare white European. I see another, a Russian, as he receives his certificate of citizenship, which is about the size of a diploma and adorned with seals and signatures—the kind of thing one frames and hangs on a wall. With a fitting eloquence, akin to that of an evangelical pastor, the presiding judge, Paul Davison, a subtle and affable African-American, congratulates us on attaining U.S. citizenship. He informs us that we hail from 46 different countries; he exhorts us to “contribute to the diversity that makes America strong.” It’s hard for me to imagine a magistrate from anywhere else inviting you to become a citizen while renouncing nothing of your culture and beliefs.

Not all American citizenship ceremonies are alike, however. A month later, on the day after Veterans Day, my wife, Marie-Dominique, in turn becomes an American. The tone for her ceremony was martial. With several soldiers being naturalized as thanks for serving in the American military, the judge praises the armed forces. Even under President Barack Obama, America is not pacifist. It never is. From its founding by George Washington, and with a brief interlude from 1920 to 1940, the U.S. military has been constantly at war—on the frontiers, during the nineteenth century, or far away. Marie-Dominique is invited to wave a little paper flag and to sing “America the Beautiful.”

She is joining me in my American adventure solely out of faithfulness, as she doesn’t share my identity troubles. Her genealogy goes back several centuries, rooted in the loveliest part of France, between Angers and Nantes, with a few family offshoots toward Sable and Bressuire. Marie-Dominique is a contemporary manifestation of those strong women of the Vendée described by Michelet, who, if he is to be believed, laid down all the rules of conduct during the eighteenth century, even pitting their husbands against the Republic when it went crazy during the French Revolution’s Terror.

Can someone be at once French and American, without conflict? I liked the fact that, in order to become an American, I actually did not have to renounce my French nationality. This right of dual citizenship between France and America goes back to 1778 and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, signed by Conrad Alexandre Gérard (under the direction of Louis XVI’s minister Vergennes) and Benjamin Franklin, America’s ambassador. The right opened up the possibility, for example, for American Thomas Paine to be elected a French deputy from Pas-de-Calais during the 1798 Convention. It’s worth recalling in this context that without the support of Lafayette and of Admiral Rochambeau—the first for public relations in the court of Versailles and the second at sea, off the shore of Yorktown—there would have been no United States.

The Constitution is a central totem of American society, not at all like the French document, which has varied ceaselessly with regimes, majorities, fashions, and partisan calculation. And the American Constitution is what I promised to defend, not the United States itself; if the government somehow broke faith with its founding document, our agreement would be done. (The president, too, is pledged to protect only the Constitution, though you wouldn’t know it from recent White House occupants, who claim that they took an oath to defend the American people. They didn’t.)

This Constitution of 1787, with its first ten amendments, the famous Bill of Rights, is the quintessence of Enlightenment philosophy, completed by two subsequent key amendments—one inscribing formal equality between the races, in 1865, and the other, in 1920, ensuring the civil rights of women. From its first words, the Constitution distinguishes itself from all other political proclamations: “We the people,” it begins—that is, you and I, and not the Nation, an abstraction that puts the individual in a box with a label. I’m also moved by the Declaration of Independence of 1776, which Judge Davison reads to us at the beginning of the citizenship ceremony. The Declaration introduces, besides the ideals of liberty and equality—announced 13 years before the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen—another right, previously unknown in human history: the right to the pursuit of happiness, a striking formulation conceived by Thomas Jefferson. These texts, which Americans hold sacred, have protected them from totalitarian ideologies and from the excesses of their presidents, as when Richard Nixon was forced to resign and Bill Clinton barely escaped removal from office for lying under oath.

On a video screen, President Obama welcomes us as new citizens, whom he is counting on to help the United States remain a “beacon to all nations.” Americans, of course, see themselves as “exceptional,” and they are: no other nation had ever been founded on a contract and on the personal will of citizens to adhere to it. We all applaud Obama’s short speech—the only spontaneous enthusiasm shown by this calm group. Perhaps the lack of open excitement reflects the culmination of a boring administrative process that had begun years earlier. By the time I found myself in the jury room, I had filled out countless questionnaires, conducted frantic searches for missing documents, and talked with numerous immigration officials, not all of them friendly. Making my way to the end of the bureaucratic marathon took up ten years of my life.

At the end of Judge Davison’s speech, each candidate gets called up to receive the citizenship certificate. Many fail to respond at first because they don’t recognize the American pronunciation of their names. I had once made immense efforts in France to adopt a French name, rather than one that was Jewish or Germanic (from Berl Somann, I became Guy Sorman). Here, I was transformed into an American instantly—I was no longer “Gee” (with a hard g, as the French pronounce my name) but plain old “Guy,” rhyming with “eye,” which, in America, is also a generic term for a male (or, in groups, males and females). In America, my family name is now pronounced, unlike in France, with the n vocalized. In these different pronunciations, I find confirmed my desire for multiple identities. For many of my fellow new citizens, vital necessity drove them to America: escaping from poverty, civil war, and dictatorial governments, they will now, at last, be able to live normal lives in a civilized country. For me, dual citizenship represents a cultural choice.

When my turn comes, I step forward. The pressing crowd leaves me no time to converse with Judge Davison. I manage a single sentence: “Today, I have obtained what my father sought in 1933.” The judge held my hand in his for a moment. “You did this for your father,” he says.

Becoming an American has indeed been all about waiting. The waiting began in 2005, when Marie-Dominique and I decided that we wanted a new life that only the United States would allow, since it did not require us to renounce our French nationality. Approximately 1 million immigrants come to the U.S. every year, as well as another 1 million undocumented aliens. Because the nation’s reopening to large-scale immigration in the mid-1960s was accompanied by a desire to diversify the population, it became easier for people from China, India, or Mexico to become citizens than it would be for Europeans. Half, at least, of the immigrants naturalized during my ceremony were from Central America and South America; the next-largest contingent was probably Indian or African. Most were likely joining family members already in America, which can make the process easier. For my wife and me, Europeans without relatives in America, the path was more arduous, involving legal difficulties that required a lawyer’s aid to navigate.

In the United States, a lawyer is more than a judicial assistant who manages your legal procedures; he is your counselor, your notary, and your tutor. Europeans pay more in taxes than Americans do, but administrative rules tend to be clearer than in America, where their complexity acts as a hidden tax. Without a lawyer—an expensive one, if he or she is competent—an American or prospective American could easily wind up lost in a legal labyrinth. To compare honestly the costs of government in France and the U.S., legal fees should be added to the known fiscal burden. The fees, which cover the many steps of the immigration process, are onerous enough to explain the booming industry in fake identity papers used by many illegal immigrants. For illegals, the risk of carrying such fraudulent documents is minimal: unless they try to leave American territory, they’re unlikely to have their phony papers closely checked.

For someone who wants to become a real citizen, however, legal representation is a big help. And over the course of ten years, our lawyer guided Marie-Dominique and me through a snakes-and-ladders game of administrative cases, each step allowing us to stay longer in the U.S. and giving us ever more American rights. From the ordinary visitor’s visa of three months, we made our way to a six-month visa, and then to the “0-1” visa, reserved for “exceptional individuals” who can make a significant contribution to American society. The 0-1 visa remains time-limited and does not establish residency, but it enables one to work for longer periods.

Never have I considered myself an “exceptional” person in this sense, capable of contributing something that some American would not be able to do just as well. But my lawyer demonstrated that I was the only one in the world in my particular discipline—a discipline she invented for the occasion. After examining my writings and their translations into many languages, including some without global scope, she concluded that I was the leading scholar in the analysis of the relations between rates of economic growth and the culture of poor countries, such as the level of trust among individuals or toward government institutions. This claim wasn’t false in describing my work’s intention, but it exaggerated my originality and success. The volume of my writing seemed as decisive as its content, however, since this expert in 0-1 visas gathered together all my books, including translations, and a multitude of essays, both by me and about my work, and sent the whole pile to the relevant immigration office.

Next comes the Green Card that millions of immigrants dream of obtaining. It confers the rights to reside and work in America, and to leave and return to the country as one desires, though it doesn’t allow one to vote. Green Card status also requires one to declare his or her income, whatever its source, to the Internal Revenue Service. One can deduct from federal taxes what one has paid elsewhere, however, and since I pay high French taxes, I never owe the IRS much. The sizable bill that I do have to pay every year stems from what I owe the accountant who sorts out the tangle of U.S. tax rules. Here again, the American government might seem less burdensome for taxpayers than the French one, but its needless complexities amount to a vast hidden charge.

One disappointment: the Green Card is only green-ish, not really green. And another: instead of passing into your hands in a solemn ceremony or via a federal agent who’d say, “Welcome to the United States” as he handed it to you, the Green Card arrives in the mail. That means waiting for the daily mail delivery . . . and waiting. My wife, for whatever reason, received her Green Card three weeks before I did. Suffering from a hereditary malady that might be called “Ashkenazi paranoia,” I was certain that I’d been forgotten, but my card eventually arrived, mixed in with seasonal catalogs and bills.

Not the least of the Green Card’s advantages is that one can now use the airport lines reserved for citizens and residents. Foreigners who, after an eight-hour flight, must stand an hour or longer to get past the customs counters at Kennedy or Newark International Airports understand the value of this privilege.

The interminable waiting that I once had to suffer through was an initiation into the phenomenon of the line in the United States. To wait in line is, for Americans, fundamentally democratic. We—and I can say “we” now—wait at the bank, at the post office and other government offices; everywhere. Americans are supposed to keep calm in line, accept that no one has special privileges, and acknowledge the country’s egalitarian ethos. When I notice a tourist waiting impatiently, grumbling or trying to cheat ahead a few places, I feel like saying: “This is the United States, and here’s your first lesson in democracy.” In my experience, some have more trouble than others in adapting—in particular, the Chinese. Coming from a country without law and without orderly lines—since one’s rank, including in lines, is determined by power and corruption—they can find it hard to wait their turn in the new, regulated American order.

The French aren’t far behind the Chinese in their exasperated impatience, as exemplified by the behavior some years ago of Azouz Begag, a minister for then–French president Jacques Chirac. Invited to give a speech in Atlanta on race and integration, Begag faced a long wait to get through customs at Atlanta International Airport. Begag wouldn’t tolerate such a delay. After all, what was the point of being a government official if one didn’t get served first? Begag had not come to America in his ministerial capacity, though, but to participate in a conference. “Get back in line with everyone else,” officials told him. Begag, a sociologist and former student at Cornell University, should have accepted this verdict with greater equanimity than the typical Frenchman, but, alas, he protested vehemently, brandishing his diplomatic passport. Two police officers swept in, handcuffed him, and threw him in the airport’s makeshift jail. A few hours later, the French consul liberated him. With hindsight, Begag told me, he recognized that he had offended America’s democratic spirit.

“It’s possible to have a complex, plural identity, so long as one loves democracy’s diversity and detests nationalism.”

Through the entire bureaucratic maze I traveled in my quest for citizenship, I have gone through countless scanners and zig-zagged through endless roped-off zones, holding my computer-generated tickets, waiting for my number to come up so that I could sit before a high-ranking officer in charge of my case. In my journey of initiation, I tried not to lose patience and to remain courteous, just as most of my interlocutors were. There seems to be an unspoken rule that the immigration officer, who’s never seen you before, calls you by your first name. This is another lesson in American democracy—for a person’s family name tends to situate him socially and ethnically more often than does his first name. My first name, in its simple American pronunciation, made it easy for immigration officials; my wife’s name, Marie-Dominique, harder to Americanize, led many of them, especially women, to call her “honey,” or some variant thereof. One cannot imagine a French immigration official ever calling someone ma chérie.

The final barrier to overcome for citizenship is an in-depth interview with an immigration officer. Your lawyer attends, to ensure that the correct procedure is followed, but does not intervene in the examination. And this is indeed an exam. The officer assesses your ability to speak and write English—but only for a small number of words, the list of which is available in advance. Candidates lacking English fluency memorize this list. Some questions follow, to verify that the candidate for citizenship knows something about the country and its political institutions. Out of 100 possible questions—these, too, available in advance—ten will be asked, and the candidate must answer six correctly. Some fail because they didn’t take the test seriously enough, or because their English is too poor for them to understand the questions properly, or because the political subject matter escapes them. They can retake the test a few months later. One question I received: How many amendments to the Constitution are there? Correct response: 27. That one was tough, but others were ridiculously easy. What continent did African-American slaves come from? Well, Africa. Name a Native American tribe. I chose the Cherokees. My wife surprised her examiner by knowing that Albany was the capital of New York, something I’d bet half of New Yorkers were in the dark about.

All this mostly describes, but doesn’t fully explain, my presence in the Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse on October 16, 2015, my oath to a flag that I couldn’t see, and my handshake with Judge Davison. The deepest reason was grasped by the judge at the time: my father’s memory. He wanted to become an American, but he didn’t make it. I wouldn’t rest until I was one, to honor him and complete his journey—or, more precisely, his escape, hunted as he was by Stalin, Hitler, and Marshal Pétain. My double citizenship not only fulfills my familial odyssey, however; it also demonstrates that it’s possible to have a complex, plural identity, so long as one loves democracy’s diversity and detests nationalism, which ruins souls as much as nations.

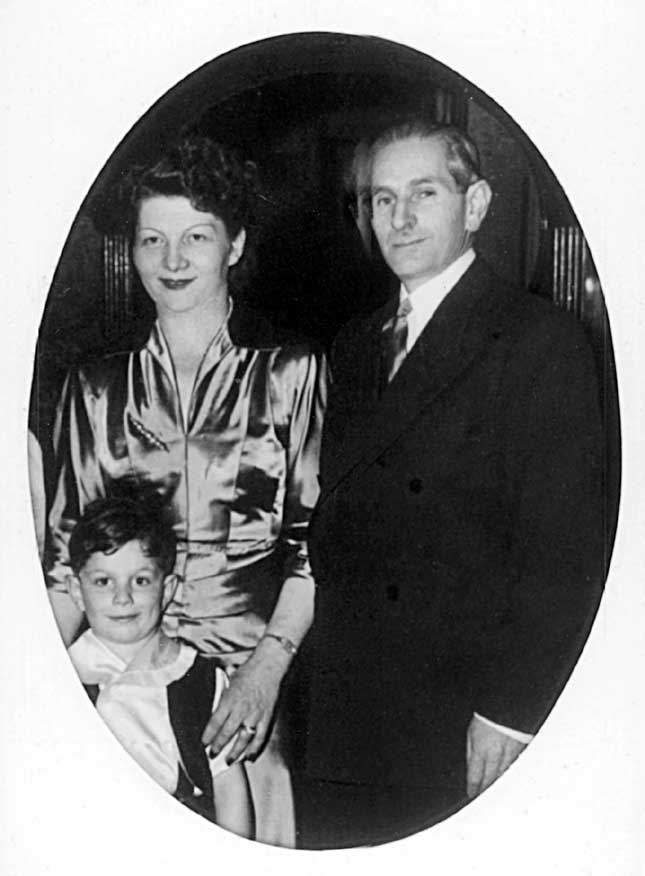

Top Photo: The right of French-American dual citizenship goes back to a 1778 treaty between the two countries. (Private Collection/Bridgeman Images)