Be sure to receive our expert commentary on racial preferences and other issues. Sign up for the City Journal newsletter today.

Read more of our affirmative action and preferences coverage here.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The consideration of subjective factors like diversity, equity, and inclusion in school admissions presents profound legal and moral questions, but it also gives rise to an empirical one: When students are admitted to highly selective schools for which they may not be academically qualified, do they suffer from being “mismatched” with their more qualified peers?

Manhattan Institute fellow Robert VerBruggen recently published an issue brief looking at this question as it applies to college and university admissions. The answer, research suggests, depends on two factors: the extent of the admissions boost that an applicant receives from affirmative action, and the type of college or university program in which the applicant later enrolls. As one might expect, the greater the admissions boost, the more likely that the applicant will suffer from mismatch. Similarly, the more selective the school or the more difficult the course of study, the greater the chance that mismatch will occur.

Mismatch theory tends to be studied within the context of higher education, but I can’t help but be reminded of a controversy that has embroiled San Francisco’s storied Lowell High School for the past year.

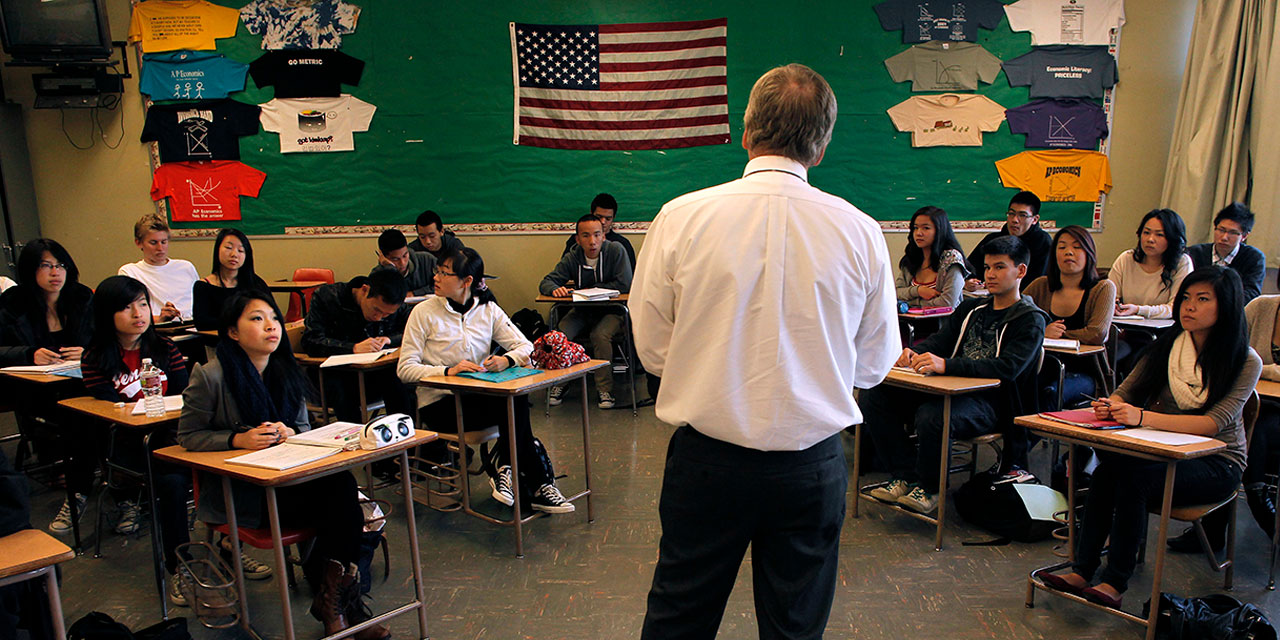

Founded in 1865, Lowell is the oldest public high school on the West Coast. It is ranked as one of the highest-performing schools in the Golden State and has been recognized four times as a National Blue Ribbon School, eight times as a California Distinguished School, and once as a Gold Ribbon School. Among the ranks of Lowell’s alumni are Noble laureates, Pulitzer Prize winners, a former Supreme Court justice, a U.S. ambassador, and numerous CEOs. Lowell is also one of the country’s few selective public high schools (or exam schools), meaning that it uses selective or merit-based admissions, in the form of grade- and test-score cutoffs, to assess applicants. Many San Franciscans view admission to Lowell as the first step to success—to be followed up with admission to top colleges, plum white-collar jobs, and eventually a secure spot in the middle or upper-middle class.

On February 9, 2021, the San Francisco School Board voted to replace permanently Lowell’s merit-based admissions program with a lottery-like system, something it had done temporarily for its fall 2020 admissions cycle, when the pandemic rendered universal standardized testing requirements hard to enforce. In justifying its decision, the school board cited diversity, equity, and inclusion concerns, noting that, prior to the 2020 change, fewer than 2 percent of Lowell students were black and only 12.5 percent were Hispanic, while 25 percent were white and nearly 50 percent were Asian-American. By contrast, Lowell’s incoming class for 2021—the first class admitted under the lottery system—was 5 percent black, 22 percent Hispanic, 18 percent white, and 38 percent Asian-American.

The school board’s decision angered families and generated a flurry of lawsuits and complaints. But Asian-Americans appeared most outraged, believing that the change in admissions policy had specifically targeted them. These suspicions seemed confirmed when Diane Yap of the Friends of Lowell Foundation, an organization dedicated to protecting merit-based admissions at the school, discovered a series of anti-Asian tweets from the school board’s vice president, Alison Collins, in which she accused Asian-Americans of using “white supremacist thinking to assimilate and ‘get ahead.’”

San Francisco’s Asian-American community responded by spearheading the (successful) effort to recall Collins and two other progressive school board members in a February election. Apparently chastened by the backlash, the school board voted last month to reinstate merit-based admissions at Lowell, at least for now.

Recent data obtained by the San Francisco Chronicle may shed some light on the question of whether mismatch theory holds true even in the context of selective high schools like Lowell. The data revealed the numbers of D and F grades that teachers at Lowell gave freshman students this past fall—the first semester after the school board eliminated merit-based admissions.

Those numbers suggest that the answer to the question may be “yes.” Of the 620 students in Lowell’s freshman class, 24.4 percent received at least one D or F grade during the fall semester, compared with 7.9 percent of first-year students in fall 2020 and 7.7 percent in fall 2019.

Opponents of merit-based admissions at Lowell, like the high school’s former principal Joe Ryan Dominguez, have argued that this surge in low grades among the most recent freshman class is unrelated to the lottery system. Dominguez told the Chronicle in an email that “there are way too many variables that contributed” to the rise in Ds and Fs: “Over a year of distance learning, half of our student body new to in-person instruction at the high school level, and absences among students/staff for COVID all explain this dip in performance.” He then added: “It is important not to insinuate a cause on such a sensitive topic at the risk of shaming our students and teachers who have worked very hard in a difficult year.”

But it’s not shaming students and teachers to point out that, when remote learning began at Lowell in fall 2020, only 51 freshmen—from the last class admitted through the merit-based system—received a D or F grade. This number tripled to 152 in 2021, after the introduction of the lottery system. Moreover, other high schools in the city didn’t see a rise in students receiving a D or F grade that fall, according to aggregate data for grades 9-12 provided to the Chronicle by the district. In fact, the share of freshman D or F grades in reading, math, science, and social-science classes declined citywide between fall 2019 and 2021, suggesting that the school board’s decision to replace the admission system likely contributed to the increase in low grades among the school’s ninth-graders.

Indeed, several students and teachers at Lowell have said as much. When told about the preponderance of low grades among Lowell’s freshman class, Teagan Robinson, a junior, said to a Chronicle reporter: “That’s crazy. While I don’t blame these kids, I think the lottery puts them in a worse situation.” Lana Wallace, another junior, said: “If the lottery system continues, Lowell classes will definitely get easier because students won’t be able to handle how it is now.” Mark Wenning, a biology teacher who has taught at Lowell for the past 25 years, told The New Yorker: “I have three times as many students as usual failing—instead of one or two I have three to six. I have some students who have done no work the whole first grading period.”

The San Francisco School Board’s short-lived decision to replace merit-based admissions at Lowell with a lottery system should serve as a warning for other school boards around the country considering similar moves, such as Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia and Boston Public Schools in Massachusetts. If school boards want to expand opportunity for disadvantaged students, they should leave exam schools alone and focus instead on increasing tutoring services, one-on-one mentoring, and individualized college counseling and preparatory programs in their district’s high schools.

San Francisco’s Mission High School, long known for its problems with gang violence, recently adopted this approach through its program Mission Graduates. The results speak for themselves. Of the 83 Mission High students who applied to the University of California for the 2021–2022 school year, 90 percent were accepted, a higher proportion than any other school in the San Francisco Unified School District, including Lowell. Of the 150 Mission High students who applied to California State University, all were accepted. Almost all the students enrolled in Mission Graduates, program director Amanda Posner told the San Francisco Examiner, are low-income, first-generation students. (And it’s worth noting that Proposition 209 of the California state constitution prohibits affirmative action in public college and university admissions.)

Admitting students to selective schools for which they are academically unqualified does them no favors—but as Mission High shows, providing them with additional support and guidance can put even the most disadvantaged high schoolers on a path to greater success.

Photo By Michael Macor/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images