Located on the Southern Plains, far from America’s coasts and great river systems, the Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan area epitomizes the new trends in American urbanism. Over the past decade, DFW has grown by some 1.3 million people, to reach a population of just under 7.7 million, making it the nation’s fourth-largest metro, based on new figures from the 2020 census. Rather than building on natural advantages, the metroplex owes its tremendous growth to railroads, interstate highways, and airports, plus an unusual degree of economic freedom and affordability.

There’s an adage in Texas about a braggart being someone who’s “all hat and no cattle.” But you can’t say that about “Big D,” rapidly emerging as the de facto capital of the American Heartland. The DFW metroplex is now home to 24 Fortune 500 company headquarters, trailing only New York and Chicago; 40 years ago, the region had fewer than five. DFW’s economy has grown markedly faster than those of its three largest rivals (New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago), and it has come through the Covid-19 pandemic with less employment loss than any other metro among the nation’s 12 largest.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

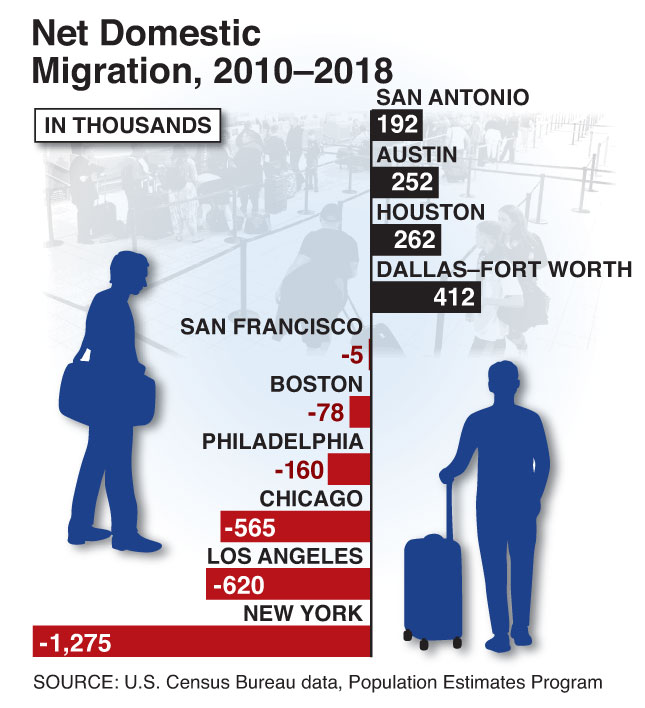

Population, too, has surged almost three times faster than the average for the nation’s 50 largest metros. Much of this growth has come from net domestic migration: among America’s top 20 metros, DFW boasts the fourth-highest rate of net inbound migration (including millennials), and the area has experienced a massive surge in its foreign-born population. Demographers project that DFW will reach 10 million people sometime in the 2030s, surpassing Chicago to become America’s third-largest metro area.

Dallas–Fort Worth is emerging as a megacity but a distinctly polycentric one—more like Los Angeles than New York or Chicago. As of 2017, the Dallas central business district contained only 11 percent of DFW’s total office space and only 5.2 percent of the region’s office space under construction. Even including Fort Worth’s smaller downtown, the area has a smaller share of its office space in traditional downtowns than almost any other large American city. Since 2010, more than 87 percent of the metro area’s population growth has been outside the city of Dallas, as has virtually all the region’s job growth. That growth has been concentrated in two corridors: one stretching from the northern suburbs almost to the Oklahoma border; and another radiating outward from downtown Fort Worth.

At the same time, some of the region’s core urban areas, particularly Southern Dallas, continue to struggle. If DFW is really going to vault into the ranks of top-tier global cities, it will need to offer not just suburban safety and quality of life but also more options for those who want to live in a traditional urban setting, as well as better economic opportunities for residents of neighborhoods that have been left behind.

Farmer and lawyer John Neely Bryan founded Dallas in 1841, when he claimed a plot of land on an eastern bluff overlooking the Trinity River. Settled after the Civil War by Confederate veterans (Bryan himself served as a Confederate soldier) and freed slaves, the Dallas–Fort Worth area unequivocally belonged to the South in its attitudes and social relations up to the early twentieth century.

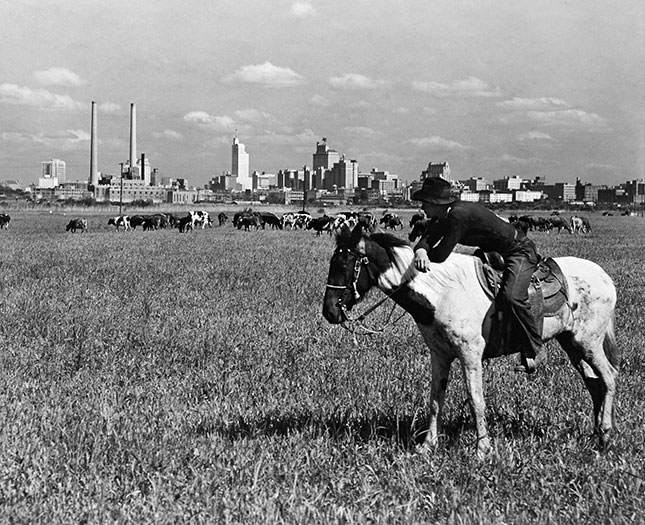

Between 1880 and 1900, the city of Dallas grew fourfold, exceeding 40,000 in population, based on its position as a railroad junction and a cotton-trading hub. Fort Worth, meantime, boomed in the late nineteenth century as a key stop on the great Western cattle drives. Early on, the region developed a reputation as a violent, riotous place—a Wild West outpost known for spawning legendary figures from Doc Holliday to Bonnie and Clyde, as well as carousing cowhands and other unsavory sorts.

In the early twentieth century, the Texas oil boom raised the region’s profile, making Dallas a local financial center. Still, the state’s economy depended on resource extraction, an industry controlled by the big eastern cities. Texas remained, in the words of governor (and Dallasite) Pappy O’Daniel, “New York’s most valuable foreign possession.”

But even as they genuflected eastward, the young city’s business leaders had big plans and a talent for self-promotion. As Fortune observed in 1949, “Dallas doesn’t owe a thing to accident, nature, or inevitability. . . . It is what it is . . . because the men of Dallas damn well planned it that way.” Starting in the 1930s, the Dallas Citizens Council, a business group representing what historian Darwin Payne has called “the local oligarchy,” remade the city, building parks and cultural institutions, promoting the growth of Southern Methodist University, and creating annual tourist attractions—especially the State Fair of Texas and the Cotton Bowl college football classic.

Their efforts paid off. New York travel writer John Gunther dismissed Houston as uncouth and money-obsessed in a 1946 profile but praised Dallas as “a highly sophisticated little city,” with fine hotels, restaurants, and department stores, epitomized by Neiman Marcus. Gunther described downtown Dallas as “a mini-Manhattan.”

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas in November 1963, coupled with an ultraconservative streak among some of the city’s businessmen, brought Dallas a less welcome reputation as a “city of hate” (though JFK, it is often forgotten, was murdered by a devout Communist, not a right-winger). But business leaders emerged from this crisis more determined than ever to put the city’s past behind them and embrace a path of growth and modernization. Led by Erik Jonsson, a cofounder of Texas Instruments who became the city’s most consequential mayor, they built what became the preeminent art scene in the south central United States and secured a National Football League expansion franchise—the Dallas Cowboys—that went on to establish an improbable global brand as “America’s Team.”

More important, the business leaders built a first-tier transportation network, centered on Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport but also including a premier national hub for ground logistics and a toll-road system that could support rapid outward growth. DFW Airport, opened in 1974, has reinforced the North Texas region’s position as a national crossroads. Thanks to the airport, traveling businesspeople can reach every major city in the United States within four hours, plus 66 nonstop destinations outside the United States. DFW is the world’s 12th-largest airport in passenger numbers, as well as one of America’s leading cargo airports.

The region’s central location and efficient transportation infrastructure have given the DFW metroplex a vital edge over competitors in attracting corporate relocations and expansions. Mario Hernandez, a longtime authority on economic development in Texas, says that Dallas is all about “the servicing of the American economy, the linking of the two coasts. When the country thinks about the middle of the country, they think about the Dallas–Fort Worth area . . . . It’s a checkmark on the list of factors when it comes to proximity to the two major coasts and of being able to serve the Midwest and, at the same time, all the way down into Mexico.”

Today, Dallas is pulling away economically from the nation’s long-established urban centers because of a distinctive policy orientation: growth-friendly, with lighter-touch business regulation and lower taxes than longtime urban centers in the Northeast, the Midwest, or California. Only four of the 53 U.S. metros with more than 1 million people outperform DFW on an index of economic freedom measuring tax levels, government spending, and labor rules developed by economists at SMU’s Bridwell Institute for Economic Freedom. Likewise, only five of these metros have more growth-friendly land-use rules, based on a data set compiled by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

These factors have helped the region amass major advantages on living costs and costs of doing business over the largest metros of the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast. According to one measure, Texas’s cost of living is about 6 percent below the national average, while California’s is about 40 percent above. Median home prices in DFW were 4.3 times median household income in late 2020, compared with an average of 5.6 times median household income in the nation’s 20 largest metros and as high as nine times in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Silicon Valley.

DFW’s location and cost advantages have become powerful magnets for businesses. Already home to the headquarters of well-established companies like Texas Instruments, American Airlines, Southwest Airlines, Kimberly-Clark, and DR Horton, DFW in recent years has rapidly acquired headquarters for such elite companies as the California-based Jacobs Engineering, Fluor, Toyota Motor North America, McKesson, Tenet Healthcare, CBRE, and Charles Schwab.

Count Bob Pragada, chief operating officer of engineering giant Jacobs, which moved to Dallas in 2017, among the converts. “If you had asked me whether my family and I would be in Texas, I would have said you must be smoking some funny stuff,” the Chicago native and son of Indian immigrants said. But high living costs, particularly for housing, made the Los Angeles area increasingly prohibitive for his 36,0000-employee firm. “If you’re not a tech company, it’s very difficult to be in California,” he said, adding that it was getting harder to persuade employees to move there.

By contrast, firms coming to Big D generally report success attracting employees. Toyota numbers among the recent transplants, relocating more than 3,000 jobs to Plano for its opening in 2017, including from its former Torrance, California, headquarters. “About 70 percent of our team members made the move with us,” says Chris Nielsen, executive vice president of the Japanese automaker’s North American operation. “We hired about 1,200 new team members. Of those, the vast majority was from the North Texas region. We found great talent here.”

DFW has also established itself as America’s third-largest financial center. The area’s dispersed financial institutions may not look like those associated with Manhattan-style density, but they’re growing. Comerica moved its headquarters to Dallas from Detroit in 2007, and Charles Schwab and First Foundation moved more recently from California. State Farm and Liberty Mutual have opened large operations in recent years, too, in Dallas’s northern suburbs. Even Nasdaq is reportedly considering a move to Dallas from the New York area.

Recent shifts in domestic migration patterns are reshaping the DFW area, as well as the other large metros of the flourishing Texas Triangle region—Houston, San Antonio, and Austin. From 2010 to 2020, DFW saw net inbound migration from elsewhere in the United States of more than 430,000—more than any other U.S. metro—and inflows of young families have given DFW a more youthful population than most. In 2018, DFW’s median age was 35.1, compared with a national metro average of 38.5.

Increasingly, these newcomers come from the coasts and the Midwest. The region received more than 100,000 migrants from the Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago metros between 2012 and 2016 alone. North Texas now boasts the fifth-largest labor pool for tech talent in North America, according to a study by commercial real-estate firm CBRE. Migration is also making Dallas–Fort Worth more diverse. According to a study by the Urban Reform Institute, black and Hispanic residents do better in terms of income, homeownership rates, and overall living standards in DFW than in most other U.S. metros, and they’ve voted with their feet. The last decade has seen a growing exodus of blacks and Hispanics from northern and western cities and a large influx into Sun Belt metros like Dallas–Fort Worth. Beck Construction CEO Fred Perpall, an African-American who recently served as board chair of the Dallas Citizens Council, says that Dallas is “an extraordinary place to grow a business and have a great quality of life. . . . I don’t think there’s another place in the country where a professional can earn what they do here and have this quality of life.”

Particularly notable has been the growth of the Hispanic population, which has expanded to more than 28 percent of DFW’s population today, from just 7 percent in 1970. Maryanne Piña-Frodsham, who grew up in the border city of McAllen, Texas, came to Dallas as a young adult, founded Career Management Partners, a firm specializing in minority recruitment and job placement, and built her company into a $5 million business with 56 employees. “The American dream stereotype still exists here,” she notes. “If you work hard, you can make it. It’s still up to you as an individual.”

Piña-Frodsham sees Texas as a state “changing rapidly” through immigration. According to Census Bureau data, foreign-born residents made up nearly 21 percent of DFW residents aged 25 and over with a bachelor’s, graduate, or professional degree as of 2017; that’s 25 percent above the national average. Over the past decade, notes demographer Wendell Cox, DFW has expanded its foreign-born population by 30 percent, more than any of the seven U.S. metros with more than 5 million people; foreign-born populations basically flatlined in New York, while dropping, in absolute terms, in Los Angeles and Chicago.

A newcomer like Mehdi Peikar, an immigrant from Iran, could have located his startup firm, Brius, in Washington, New York, or Los Angeles—all places with established Persian communities. But in putting together his company, which uses digital technology to adjust orthodontic braces, Peikar was drawn to Dallas’s talent pool, low costs, and growth-friendly environment. “There’s a lot of talent here,” the 35-year-old dentist suggests. “And with the lower costs, it’s simply a better place to build the business.”

The epicenter of the North Texas boom lies in Collin and Denton Counties, north of Dallas. Suburban communities outside the region’s two core cities accounted for roughly three-quarters of the metro’s population growth over the past decade. Collin and Denton Counties have a combined population of 2 million, larger than all but four U.S. cities. Together, the population of the five largest suburban cities in these counties—Plano, McKinney, Frisco, Denton, and Allen—roughly doubled from 2000 to 2019 and now exceeds the population of San Francisco.

According to Perpall, these suburban cities have excelled at building out infrastructure ahead of surging population growth and creating “plug-and-play” opportunities for relocating firms. They also offer outstanding public schools, low crime rates, and far better affordability than the core city of Dallas. Consequently, they’re seeing not only the lion’s share of population growth in North Texas but also a disproportionate share of corporate relocations to the region, including Toyota and Liberty Mutual, as well as expansions from firms like Peloton Interactive, Qualtrics, and Aimbridge Hospitality. The northern suburbs constitute an increasingly self-contained economic system, dominating DFW’s employment in technology, telecommunications, and back-office processing industries. Jobs in the leading cities of Collin and Denton Counties are growing faster than population, and the daytime working population in these cities roughly matches the population of working residents who sleep there at night.

These cities’ foreign-born population share is as high as that of Dallas, while their combined Hispanic and black population now amounts to more than 20 percent of total population. McKinney saw its Hispanic population grow 36 percent and its black population more than double between 2010 and 2018. According to the recent Urban Reform Institute study, median living standards are 19 percent above the DFW average for Hispanic households and 46 percent higher for black households. Meantime, Collin County’s Asian-American population, at 16 percent of total population, far exceeds that of Dallas’s 3 percent. The northern suburbs now feature a wide array of Asian restaurants, Chinese New Year festivals, cricket fields, and other signs of the area’s changing demographic makeup.

The other growth corridor in the region radiates outward from downtown Fort Worth to the north and west. Fort Worth long lived in Dallas’s shadow, but the Fort Worth side of the metro area has experienced explosive growth over the last quarter-century, emerging as a diverse, dynamic economy with a rich portfolio of manufacturing and service-sector industries. Fort Worth is arguably more representative of the qualities that attract people to the Texas Triangle region than Dallas. It’s more affordable, with less traffic congestion, a more vibrant downtown, and a laid-back vibe.

Fort Worth’s population has grown from 46 percent of Dallas’s level in 1970 to 67 percent today. Alliance Airport, founded by Ross Perot, Jr. as the nation’s first pure cargo airport, has cemented the region’s position as a national logistics center and sparked growth on the northern edge of the city. Elaine Agather, managing director of the central region for J.P. Morgan Private Bank, says that Fort Worth is in the process of turning its Western “rodeo swagger” into “economic growth swagger.”

Amid much success, though, DFW is struggling to forge greater economic vitality in its vast left-behind areas, especially Southern Dallas and southeast Fort Worth. Southern Dallas, defined as the area south of Interstate 30, accounts for 60 percent of the landmass in the city of Dallas but only 10 percent of the city’s assessed property value. As the region’s economic energy shifts north and west, Southern Dallas has become what Dallas Citizens Council CEO Kelvin Walker calls a “big gaping economic hole”—what many Dallasites refer to as “the giant elephant in the room.”

Some of Southern Dallas’s challenges reflect a history of segregation. Dallas became the first Texas city to impose housing segregation by law in 1916. Dallas and its suburbs fully participated in federal government-led programs between the 1930s and 1960s aimed at promoting racial segregation and concentrating investment in white areas. Dallas also engaged in “urban renewal” schemes in the 1950s and 1960s, physically destroying many black neighborhoods, including by building interstate highway connectors through black neighborhoods like Deep Ellum and Stringtown and seizing black homes to expand the parking lot used three weeks a year for the State Fair of Texas.

By the late 1960s, Dallas’s business establishment had worked out what Dallas journalist Jim Schutze termed “the accommodation”: Dallas welcomed black leaders into the city power structure, while Southern Dallas pastors ensured that the city avoided the race riots that had struck other U.S. cities in those years. But influence is different from prosperity. The low-income zip codes of Southern Dallas have seen a 17 percent decline in jobs and a shrinking housing stock since 2000, even as the wider metro area prospers. Vast tracts of space in Southern Dallas remain fallow, sometimes in relatively close proximity to downtown. Dallas County homeownership rates have declined significantly since the housing crash of 2008, with particularly large drops among blacks. Dallas ranked last in a 2018 Urban Institute ranking of 274 U.S. cities for economic inclusiveness, and segregation is rising along income lines. According to a 2015 study by urbanist Richard Florida, DFW is the seventh-most economically segregated of the 53 metros with more than 1 million people and the second-most segregated of the top ten.

Southern Dallas, an area larger than the city of Atlanta, with a combined black and Hispanic population exceeding the entire population of Washington, D.C., increasingly inhabits a world apart from the economic dynamism to the north and west. This stark geographic bifurcation remains the greatest challenge facing an otherwise dynamic region. Dallas–Fort Worth can ensure a bright future for itself only if it invests in the totality of its varied communities. Getting this right should matter not just to Texans but to all Americans, since American urbanism is shifting toward the sprawling, diverse, and business-friendly model of places like DFW.

These challenges notwithstanding, DFW seems poised for future growth. Its economy, far more than that of Houston and most other metros, is remarkably diversified. Only modestly dependent on the energy sector, for example, the DFW economy weathered the effects of declines in oil and gas prices in 2014–15 and again in 2019–20. Collin and Denton Counties are likely to see their populations more than double by 2050, and counties still farther north, along the Oklahoma border, are primed to become large growth engines as well.

America’s most economically and demographically dynamic metros will continue to play a leading role in shaping the nation’s urban geography, as they always have. In the first half of the twentieth century, the place to watch was New York. In the second half, it was Los Angeles. In twenty-first century America, keep your eyes on Big D.

Top Photo: Over the past decade, Dallas–Fort Worth has grown by some 1.3 million people, to reach a population of nearly 7.7 million, making it the nation’s fourth-largest metro. (REBECCA SMEYNE/BLOOMBERG/GETTY IMAGES)