Seth Barron talks with four City Journal contributors—Rafael Mangual, Eric Kober, Ray Domanico, and Steven Malanga—about former New York City mayor and now presidential hopeful Michael Bloomberg’s record on crime, education, economic development, and more.

After years of teasing a presidential run, Bloomberg has entered the race for the 2020 Democratic nomination. Just a week before his official announcement, he made headlines by reversing his long-standing support of controversial policing practices in New York—commonly known as “stop and frisk.” Bloomberg’s record on crime will factor heavily in his campaign, but his 12 years as mayor were eventful in numerous other policy areas.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Audio Transcript

Brian Anderson: Welcome back to the 10 Blocks podcast. This is Brian Anderson, the editor of City Journal. Former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg officially entered the race for the Democratic presidential nomination last week. One of his first public speeches before his announcement was an apology for the controversial policing practice in New York during his administration known as stop-and-frisk, which we've covered extensively here at City Journal in writing about the city's remarkable crime reduction gains during the 2000s.

But that's not the only thing Michael Bloomberg did in his 12 years as mayor of New York. During his majority the city added nearly 200 charter schools, entire new developments arose think Hudson Yards, Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City. There's the infamous ban on large sodas or big gulps as they came to be known. And other policies that we'll try to cover here today. Coming up on the show are associate editors, Seth Barron will interview four City Journal contributors to talk about Bloomberg's record on crime, education, economic development, and more. That's it for the introduction, after the music Seth Barron will begin our first discussion with Ralf Mangual to talk about Bloomberg's record on crime and policing, including the stop-and-frisk question. We hope you enjoy. Thank you.

Seth Barron: Welcome back to 10 Blocks, the podcast of City Journal. This is your host for today's Seth Barron, associate editor of City Journal. The mayoralty of New York City has long been seen as a graveyard for political ambition. Mayor de Blasio has already dropped out of the 2020 race for the Democratic nomination for the presidency and now former mayor Mike Bloomberg has entered the fray. But he's done so by walking back some key policies of his administration and some would argue the most effective aspects of his policies. I'm joined today by Rafael Mangual, fellow and deputy director of legal policy at the Manhattan Institute and contributing editor to City Journal. Ralf writes frequently on criminology, violence and public order. Ralf, thank you for joining us today on 10 Blocks.

Rafael Mangual: Thanks so much for having me, Seth.

Seth Barron: So Mike Bloomberg made some pretty controversial remarks a few weeks ago about criminal justice and what he did when he was mayor. What did he say exactly?

Rafael Mangual: Well, in essence, he apologized for what the New York City Police Department did under his watch with respect to stop-and-frisk. Stop-and-frisk as many of our listeners probably already know basically is a term of art that describes a procedure in which police in the street can stop and briefly detain a suspect they reasonably believe to be involved in a crime. And when they reasonably believe that those suspects are armed and dangerous, they can frisk the outside of their clothing and pat them down to ensure that they don't have the weapon.

Now under Bloomberg stop-and-frisk conducted by the NYPD continued to rise over the years that he was mayor. And that was one of the main points of criticism for a lot of people who sort of opposed proactive policing and most of its forms throughout Bloomberg's time in New York City. So I think he saw that as a liability for his candidacy and decided to apologize.

Seth Barron: Okay. Now stop-and-frisk as you just described it. That's what it turned out to be an unconstitutional practice. Correct?

Rafael Mangual: Well, the way that the NYPD had done it as to a group of plaintiffs that brought a lawsuit against the department was ruled unconstitutional, but stop-and-frisk in and of itself is still a constitutionally valid practice that that police, including the New York City Police Department continued to engage in to this day. The practice was recognized as constitutionally permissible in a Supreme Court case, Terry versus Ohio since that case, which is now 50 years old the Supreme Court has not rejected that prior holding. And so the actual practice of stopping people for whom there is reasonable suspicion to believe they're involved in a crime is still constitutionally valid practice.

What some courts have held throughout the years, including a federal district court here in New York, is that certain practices within certain departments around the country as to specific sets of plaintiffs violate the rule set out in that Supreme Court precedent. But that Supreme Court precedent is still constitutionally valid.

Seth Barron: So I guess I'm missing something. Who did he apologize to?

Rafael Mangual: Well, he apologized essentially to the black and Latino community as he put it. Who many critics point out were more often than their white counterparts in New York City the subjects of stops-and-frisks as reported by the NYPD.

Seth Barron: So it was a racist policy, is that what you're saying?

Rafael Mangual:Well, that's certainly how his critics will characterize it. What they ignore is that stops-and-frisks were in large part a function of how police resources were deployed.

And we know that police deployed their resources more to higher crime areas of New York City, which unfortunately were oftentimes areas with high minority population. So the fact that there were more blacks and Hispanics stopped than their portion of the population mates may suggest when you consider the number of violent crime shootings specifically committed by blacks and Hispanics in New York City. The numbers actually start to make a little more sense.

Seth Barron: He did make this one comment, and I don't know, he had said this once in the past and I guess it came back and people were talking about it, that at one point he said that white people were actually under stopped when he was mayor. Actually, that white people were over-stopped and that he should have stopped fewer white people. Does that make sense?

Rafael Mangual: Well, without the data in front of me it doesn't sound like it was particularly politically smart thing for him to say. But we do know that more than 90% of shootings in New York City are committed by blacks and Hispanics, or at least historically from the '90s through the 2000. So it really wouldn't make sense to deploy police resources, say on the Upper East Side of Manhattan where violent crime rates are pretty low as compared to East New York or Brownsville, Brooklyn, where a lot of these stops were taking place.

Seth Barron: So that's really what this was all about, the shootings. Stop-and-frisk was about reducing the number of shootings and homicides.

Rafael Mangual: It was aimed largely at reducing the number of shootings and homicides, but it also had the effect of reducing crime generally. Right? I mean this is one of the things that I don't think a lot of people appreciate, but should, which is that the increased presence of police on the street and the communication of those police to residents that they were going to be willing to get out of their cars and engage with people and initiate interactions that that prevalence, that that recognition among the general public at least among the criminal actors within the general public deterred some of their actions.

So you saw things like crime declines in the areas where the New York City Police Department was concentrating most of these stops-and-frisks. And this is again, something that I think is just unappreciated in this discussion. People, especially critics of Bloomberg these days like to point out that as the New York City Police Department started reporting fewer stops-and-frisks over time that crime did not increase.

And they see this as the kind of death now of that policy and proof positive that it was ineffective. But one study that was done in 2014 did what's called the micro geographic analysis and basically looked at the small parts of the city where an outsized portion of those stops were concentrated. And when you do that kind of analysis, when you don't use the unit of measurement... When the unit of measurement is not the city or borough, when you drill down into high crime areas, it found that there was actually a very significant deterrent effect on crime that was related specifically to the stops being conducted by the New York City Police Department.

Seth Barron: Okay. But he was the mayor of the whole city. So did murders and crime go down?

Rafael Mangual: They did significantly. I mean crime continued to decline at a very rapid pace despite very sharp declines in the 1990s prior to Bloomberg taking office, I think a lot of people would have sort of sat on their laurels or on the laurels of New York and basically said, well, look we've gotten down far and that's great.

But Bloomberg didn't do that to his credit. He continued to chase further declines and achieve them. And that I again resulted in countless numbers of lives saved over the years.

Seth Barron: Now, under de Blasio and mayor de Blasio has pointed this out, the number of stops-and-frisks is perhaps one 10th of what it was at the height of the practice under Bloomberg yet homicides and crime generally continue to go down.

Rafael Mangual: Right.

Seth Barron: So I know you alluded to this before, but doesn't that indicate that maybe there's a disjunction between the two?

Rafael Mangual: Yeah. You would think so in from a surface level that's certainly how it seems. But that counter argument fails to consider one very important factor, which is how New York City changed over those years. Right. For example, 13 of New York City's police briefings in the year 2000, just before Michael Bloomberg took office had 20 or more homicides. By the time stop numbers started to decline in 2014, that number was down to one. New York City simply had fewer dangerous neighborhoods because over those years of consistent crime decline, those neighborhoods were able to change and become significantly safer. And they did that in part by sort of growing their low crime committing populations. And that's important because irrespective of how police policy changes, you wouldn't expect low crime populations to suddenly become high crime populations. And so the fact that the city changed in these very important intangible ways means that it's not actually particularly surprising that as stops declined, you didn't see a crazy increase in crime as a result of that, because New York City was not the same city that it was when Bloomberg took office.

Seth Barron: When you say low crime committee populations, what do you mean?

Rafael Mangual: People for example, who've completed high school who have some college or have attain college degrees married households, people who are earning a middle-class salary all of these populations grew over time and a lot of the areas of New York City where that was not always the case. I mean, one neighborhood to consider would be Fort Green and Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. I mean, the face of these neighborhoods has changed in a lot of important ways. There's been a lot of economic development. And all this has resulted in a much a lower proportion of those neighborhoods having criminal actors, or consisting of criminal actors, I should say.

Seth Barron: So, Mike Bloomberg made his apology what was the effect? Did it take, did are people forgiving him?

Rafael Mangual: I'm not sure that they are. I think a lot of people are going to continue to see this as kind of a cynical political calculation. And I don't think he's probably going to get all that much credit for this, at least not from his most ardent critics. But it'll be interesting to see whether this was something that he was just kind of going through the motions on or whether this is a thread that he picks up over the course of this campaign. Is it as it grows and continues?

I mean, we know that among the democratic candidates, criminal justice reform is one of the sort of main talking points. And he hasn't yet told us where he's going to go on broader questions of criminal justice. But I think one way to kind of judge the sincerity on this will be to see whether he subscribes to the kind of broader decarceration policies that a lot of his fellow candidates are pursuing getting behind.

Seth Barron: Stay tuned as we discuss some other aspects of Michael Bloomberg's mayoralty and its implications on the coming race for the Democratic nomination. Ralf Mangual, thanks for joining us today.

Rafael Mangual: Thanks so much for having me.

Seth Barron: I'm joined now by Eric Kober. Eric is a retired New York City planner and currently adjunct fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. Eric, thanks for joining us.

Eric Kober: Thank you.

Seth Barron: So what can you tell us about how Mike Bloomberg... What was his approach to planning the city? What did he do in terms of building it out, economic development, zoning, housing?

Eric Kober: Well, I think that first of all, he delegated those responsibilities to a very strong team and he had a strong team throughout his 12 years. But initially the deputy mayor for economic development and rebuilding was Dan Doctoroff. The chair of the city planning commission was Amanda Burden and the commissioner of housing preservation and development was Sean Donovan. And they saw their task really as putting the city on a sound economic footing for the long term. They were coming out of the recession that followed 9/11. The city clearly had a problem with short term fiscal stabilization but they really saw their goal as setting the city up so that it would no longer be subject to the boom and bust cycles of economic growth and then steep recessions that had experienced over the previous several decades.

Seth Barron: So did this take the form of trying to diversify the city's economic base or?

Eric Kober: It certainly did. The city was perceived as being very dependent on the financial industry. Tech was beginning to have a significant presence in New York. It was certainly seen as a major growth sector and diversify essentially the sort of sophisticated business space that provides the bulk of the city's tax revenues either directly or indirectly, was very important. In the year 2000 during the Giuliani administration Senator Schumer had sponsored a report by what was called the group of 35 which had recommended as a sort of support for future growth particularly in the tech industry that the city rezoned three areas, Long Island City, Downtown Brooklyn, and the area of on the West side of Manhattan that ultimately was renamed Hudson Yards.

And the Long Island City resulting had proceeded in the previous administration. The Bloomberg team proceeded to undertake rezonings in Downtown Brooklyn and in Hudson Yards, which were completed in his first term.

Seth Barron: So we're talking about Barclay Center, is that what you're talking about in Brooklyn?

Eric Kober: Barclay Center was actually a state project, which was separate from the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, which was focused on the sort of core Downtown area around Fulton Street and environs. And that rezoning was oriented toward enhancing the office component of that type Brooklyn. And it turned out to be extremely successful in a different way by promoting the construction of large amounts of housing. So that Downtown Brooklyn, which had very little housing in the year 2000 now has thousands of units of new housing that had been constructed in the last two decades. A relatively small buyout of additional commercial space.

Seth Barron: And Long Island City, as we all know, has really exploded. How many new units of housing have been built there in the last 20 years.

Eric Kober: I don't have that number off the top of my head, but it's certainly in the tens of thousands of units. And again Long Island City had been intended as an office Corps and ended up seeing relatively little commercial development, but a very large number of new residential units. And that lesson was taken to the Hudson Yards rezoning where the zoning plan that was ultimately enacted put its thumbs on the scale. It really required that office buildings be constructed in what was seen as the core area, which was close to the new subway station that was constructed at 34th street and 11th Avenue.

Eric Kober: And so, unlike Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City, Hudson Yards has come much closer to the vision of creating a new office core for the growth of the cities. Most advanced sophisticated businesses.

Seth Barron: So would you say Hudson Yards has been a success or does it point the way to being a success? I mean, it's a controversial project. I mean, it's sort of fascinating to think that they paved over or platformed over and created New Manhattan. I mean, they created new blocks.

Eric Kober: Well, Hudson Yards is much bigger than just the development over the portion of the Long Island railroad yards between 10th and 11th Avenues that actually goes all the way North to 42nd Street.

The concept of Hudson Yards was that the revenues generated by new development would not only pay for the platforming over the rail yards, but also provide the revenues to pay off the bonds that were issued to build the subway and the park that was built between 11th and 12th avenues.

And in fact while the city had to pay about $300 million of interest, so to speak, out of its own pocket before development began to generate sufficient revenues. The financial goals were ultimately met in the past few years. And the bars were successfully refinanced and the city is no longer needing to support them with its own revenues. So in that sense it has been successful and it has also been successful in inducing significant amounts of new office space unlike the earlier rezonings.

Seth Barron: What about the High Line? That was a key project that happened under Bloomberg and that has become kind of a model for groups around the world looking to repurpose old rail lines, space like that. What can you say about how the High Line figures in the city landscape? Also in terms of the revitalization of that area. It hasn't been without its critics, but at the same time it is celebrated.

Eric Kober: Well, the High Line was actually a very complex project to pull off. And I think that one of the illustrative of the of the strengths of the Bloomberg team and its ability to pull off very complex projects. The highlight was an abandoned freight line. It was owned by a railroad. It had to go through the railroad abandonment process, which is mandated by federal law and ultimately was transferred to the city and reconstructed as a city park.

And at the same time the city rezoned the area around the High Line and it has become a major tourist attraction as you've said, a model for similar projects around the world. And also significant generator of new residential units as well in the surrounding blocks.

Again, the important thing here is that a plan was enacted with all the community consultation that is evolved in enacting complicated plans and successfully implemented with a lot of different moving parts that had to be put into place.

Seth Barron: Eric Kober. Thanks for joining us on 10 Blocks to discuss the development legacy of Michael Bloomberg.

Eric Kober: Thank you.

Seth Barron: Joining us on 10 Blocks to discuss Michael Bloomberg's education policies when he was the mayor of New York City is Ray Domanico. Ray is the director of education policy at the Manhattan Institute. Ray, thanks for joining us.

Ray Domanico: Glad to be here.

Seth Barron: So a lot happened under Bloomberg's term as mayor regarding the schools starting with his absorption of the power of running the schools. Well, can you talk about what that meant? The centralization mayoral control?

Ray Domanico: Sure. Prior to 2002, when Michael Bloomberg took office as mayor of the city of New York for the previous 30 years or so, the school system was run with very disjointed governance. There was a board of education of seven members. The mayor appointed two members and each of the cities, borough presidents, the equivalent of County executives and the rest of the country also appointed a person.

So no single elected official was responsible for the school system. And the school system was in really bad shape. Achievement was way down. It was not improving, the graduation rate had been stagnant at about 50% for more than 20. And by the end of the 1990s, there was a consensus that something needed to be done. And this idea of mayoral control of the school system emerged. The notion that one elected official should be accountable for the performance of the school system.

The state legislature refused to give that responsibility to Bloomberg's predecessor, mayor Giuliani, because quite frankly, they didn't like him and they didn't want to give him that power. But when Bloomberg got elected mayor, within the first couple months of his administration, he was able to convince the legislature that this in fact would be a good move.

And by six months into his term, the system was changed. So now the mayor would have the ability to hire and fire the school superintendent called the chancellor in New York City terms and have direct control over the school system.

Seth Barron: And was this a salutatory move to just help?

Ray Domanico: Yes, it was absolutely necessary. Under the previous regime, if you were displeased either as an advocate or as an individual parent with the school system, there was no place to go with your complaint. Parents would comply and that they would get shifted from office to office.

They'd go to the school. The school would say, you have to go to the district office. The district office would say you have to go Downtown. This made it more of a one stop shopping. There were clear lines of accountability for the school system.

Seth Barron: And what did he do? What did he and his chancellor do to fix the schools?

Ray Domanico: So Bloomberg obviously was mayor for 12 years, three full terms. He did a lot in those terms. I think the common element of what he brought to the mayoralty in terms of public education was a relentless focus on achievement. In contrast to the previous administration and the previous form of governance of the school system where nothing seemed to get better and also is very difficult to bring about change. The Bloomberg administration was lightning fast in terms of coming out with new initiatives. And when they were not working, they were not opposed to dropping what they were doing at pivoting and trying something different. So the common element throughout was a relentless focus on achievement.

Seth Barron: So what's an example of something like an initiative that they tried and maybe it worked, maybe it didn't work and how they pivoted.

Ray Domanico: So one of the first things they did once they got mayoral control of the school system was they tried to streamline administration in the school system. There had been since 1970 or so, 32 local school districts in the city, each with elected school boards that appointed their superintendents. On paper that system still exists today, but administratively, Bloomberg changed it dramatically in his first term in office as first couple of years, he consolidated these 32 districts into 10 regions and put 10 regional superintendents in charge.

It seemed to have some benefit to me and to others. But at the end of his first term, he decided that that was not good enough and he eliminated their regions and implemented what is now called the portfolio system. Essentially there were networks of schools in the school system that bonded together because they had similar interests and similar approaches to education rather than being organized through geography. Part and parcel of this was an embrace of school choice, which probably is the most consistent effort that Bloomberg followed in his years in office. School choice under Bloomberg in New York City encompassed two types of school choice.

Although his school system in New York City department of education was charged with running the traditional public schools in the city Bloomberg and his chancellor's embrace the possibility of charter schools. They made space available in public school buildings for charter schools and they actively promoted the growth of charter schools in the city. And their time in office 183 charter schools open.

And by the time they left office, they were close to 100,000 kids in charter schools. Starting from a base of about 1000 or 2000 before their term. The second type of choice they embraced was within the district schools themselves. They gave New York City school district employees, union members all the ability to propose the creation of new small public schools that would operate under the same rules as the public school system.

They actually opened 510 of these small schools in their term in office. And they allowed public educators to be entrepreneurial and to try new things. In order to facilitate the opening of all these new schools of choice, they also embraced a very robust system of school accountability. Schools were graded each year on a series of metrics and those that came out near the bottom were subject to closure. In fact, they closed 131 schools for low performance in their term in office.

Seth Barron: Now, I know this question of school closure became very controversial and I know when he took office mayor de Blasio very vigorously opposed closing schools and said it was a disaster for communities. What's wrong with closing a school that's not doing well? Why was this such a point of contention?

Ray Domanico: Although there was some ginned-up, supposed community support, or community opposition to closing schools. In our own work that I was involved in a previous position, we did not find opposition amongst parents to closing poor schools. They wanted better and new schools. It did create some displacement of teachers in those schools. Some of those schools, some of those teachers and schools that were closed were unable to find positions in other schools. If they were tenured, they did not lose their job, but they were placed in a pool of teachers who were circulated from school to school to fill in for other teachers. So it did create some discomfort for the teacher's union and some of their allies in the community toward particularly in a third of mayor Bloomberg's terms started staging this public opposition to school closures.

I don't believe that was very deep. I think the real issue there was not in the community but in the discomfort caused to some teachers. If Bloomberg and his chancellors could've done anything better one might fault them for not doing enough in terms of community engagement to counter that. One might argue that there's a natural process that goes on. As I say, they closed 130 of the schools over about a 10 year period. The first few years it was low hanging fruit. It was hard to defend the schools that were closing, they were so low performing. The deeper you got into it, some of the calls may have been questionable. Maybe they needed to do a little better work in convincing the public why this was necessary. I should add though, in closing on this topic, the research has been clear. The students who would have attended those schools that were closed did much better in the schools that replaced them than they would have.

Seth Barron: Regarding the teacher's union. It's thought in New York that the teacher's union effectively controls the system. To what extent is that true and to what extent did Bloomberg dismantle that system? What was the question? What was his relations with the teacher's union like?

Ray Domanico: His relations with the teacher's union were complex and they're hard to characterize. Yes, it is true before mayoral control and before mayor Bloomberg came along, it was widely and publicly said that the teacher's union was the strongest center of power in the New York State legislature. Honestly, we achieved mayoral control probably because the teacher's union finally gave its ascent to it under in mayor first couple of months.

It did appear over the mayor's term that the power of the teacher's union did wain, they did lose a couple of battles. They were opposed to the rapid expansion of charter schools, but it went ahead otherwise. They've gained back some of their power under his successor. But in terms of his own relations with the teacher's union, they were complex. I remember in his first term and parts of his second as well, there was criticism, probably valid that he gave away pretty expensive raises and other changes to the teacher's contract and perhaps didn't get much in return.

But yet he was able to pursue his agenda. So he was playing perhaps a very crafty game with the unions. Spending went up under mayor Bloomberg and I went up dramatically. And a lot of that went into teacher's salaries. This changes by the end of his end of his time in office. In his third term he did not agree to a contract for quite some time after it expired. And finally, the teacher's union decided to wait him out. So when mayor de Blasio came in, the teachers were without a contract for about three or four years. Mayor de Blasio, also gave a very generous settlement to them. But certainly Bloomberg's record here I think was very pragmatic and mixed.

Spending went up. Teachers' salaries went up, but yet he was able to get out of the system things that he wanted that perhaps the union was not too crazy about.

Seth Barron: So finally, let's talk about charter schools. This is something, I mean, this is perhaps one of his most enduring legacies from his mayoralty. Has it been positive? Is the charter experiment working? Is it going to go away? What's the story with charters?

Ray Domanico: Charter schools have been unequivocally positive on average in New York City. The best the highest scoring schools in New York State are New York City charter schools, most notably Success Academy, which is the largest network of charters in the city. These are schools that operate in the poorest neighborhoods in New York City and on the state tests at least they get reading and math scores that are better than any other schools in the state. The interesting thing about Bloomberg New York City in charter schools, and this runs counter to the narrative that one hears about charter schools, that somehow they're bad for traditional public schools.

Ray Domanico: This has not been the case in New York City. In New York City, under mayor Bloomberg the charter schools grew tremendously. They got tremendous results on average with the students that they serve. At the same time, spending both in aggregate and per pupil in the New York City district schools went up. It's not true that charter schools diverted money from the district schools. And more importantly, the results show that under mayor Bloomberg, the non-charter public schools in New York City made tremendous improvements in their test scores prior to his coming to office. The schools in New York City lagged behind the public schools in the rest of the state. By the time he left office, they were at about the state average in New York City.

So charter schools created new opportunities for students in low income communities. Largely they got very high results. But the public schools, the traditional public schools improved as well. And so this was a gain on top of a gain for New York City. It was not the case in New York that the growth of charters meant something bad happening in the district schools in the city.

Seth Barron: Interesting legacy. Ray, thanks so much for joining us today.

Ray Domanico: Well, thanks for having me.

Seth Barron: Continuing our discussion of Michael Bloomberg and his run for the democratic nomination. We're joined by Steve Malanga. Steve is the senior editor of City Journal, the George M. Jaeger fellow at the Manhattan Institute, and the author of Shakedown: The Continuing Conspiracy Against the American Taxpayer. Steve, thanks for joining us on 10 Blocks.

Steven Malanga: Fun to be here and talk about Mike.

Seth Barron: Yeah. So Bloomberg as mayor what would you say about his economic policies, his economic outlook fiscally. I mean where do we-

Steven Malanga: I mean there's two ways to break it down. One is in terms of economic policy, but probably for for people outside of New York City, what they would mostly be interested in as president is what he thought about taxes and what they thought about spending? And whether that's evolving? How he spent? And it's a kind of a complicated legacy because on the one hand, very early in his administration, he raised taxes sharply. The tax that the he as a mayor was able to raise as the property tax. And he raised it 18.5%, which is a pretty big boost considering the New York City who already has among the highest property taxes in the nation.

And the actual amount that the city collected in property taxes went up significantly during his period because they're constantly reassessing property and to his credit, the city's economy grew.

After that, he didn't raise taxes much. And he did come out, for instance, against things like a millionaire's tax in New York State, which the state legislature was trying to pass and did eventually pass at certain points. He did come out against that and talked about how you're going to chase millionaires away. Of course, people could look at that. It's self-interest because he's very much a millionaire. And on spending, I would say it's something similar early on. And he was faced with a drastic budget problem because of course after 9/11, the city's economy slowed down radically. And the city was spending lots of money on emergency services. And that was one of the reasons that he raised taxes, even though there were many people including us, who were advising him to cut other nonessential programs instead.

And he borrowed money to keep the city going. And that got a lot of criticism. Later on actually, as his tenure evolved, he became I think more careful about spending. He had handed out big contracts to city workers after 9/11, which seemed to me one of the most unwise things that he did with a big budget deficits. And because he hadn't been supported by the by the public sector union, so there wasn't like he was even paying them back, if you will for supporting him during the election. But as time went on and he actually became less willing to do those kinds of things, I think, because he saw the vulnerability that New York City had wit it's high spending to economic downturns.

And so during his whole last term, he refused to cut deals with most of the unions in the city. Because they wouldn't give him the kind of concessions that he wanted. So he kind of evolved on that. Now where he is now, it's hard to tell. It's interesting. I did, if you watch his video that's on his website, he does talk about taxing millionaires now or taxing the rich he talks about. To make America fair society.

So I guess he could justify that on the grounds that he's talking about the presidential election and not New York City or New York State where taxes are already high, but his position seems to be evolving right now.

Seth Barron: Well, he used to say that he loved billionaires and he thought New York City should have as many billionaires as possible.

Steven Malanga: Exactly.

Seth Barron: And I guess when you're running a smaller jurisdiction, like a city or a state, there is always the fear that people could flee if you tax them punitively.

Steven Malanga: And he, that was one of the reasons he upholds the millionaires tax. Yeah, absolutely. And it is a different equation nationally. Particularly because if you were to look at federal tax rates, they're not new. I mean, when you add the federal tax rates onto New York State tax rates, you get a very, very high bite on wealthy people in particular.

And we've seen, especially within the context of the Trump 2017 reform taxes which eliminate the capita deductions for state and local taxes. I mean, we have seen more and more talk of wealthy people fleeing the state. So that is an issue in Albany and in New York City especially, because that's where most of those wealthy people live.

Seth Barron: People in the Democratic Party anyway, people are going back and forth. Is Bloomberg a liberal? Is he a conservative? Is he a real Democrat? Is he a pretend Republican? You covered Bloomberg fairly closely. Would you say, is he like... People have said he's like a nanny state, big government type. I mean, how would you characterize his approach to power?

Steven Malanga: So I think what you have to do is you do have to break it down into the different areas. I think on fiscal matters, he was what I would call moderate or maybe center left leaning. And that includes, we've talked about fiscal matters. I think it also includes programs that the federal government finances, but that the States and cities run like Medicaid and Welfare. To his credit, he continued the policy of the Giuliani administration on Welfare of requiring people to migrate off of Welfare into work. He said that Welfare shouldn't be permanent. And he in fact, I guess you could say he's even expanded some of the work initiatives that the Giuliani administration had implemented. Under Giuliani the number of people on Welfare in New York City declined from 1.1 million to 500,000.

Under Bloomberg it kept declining to about 360,000. And he hired as his head of the health and human services department, somebody who firmly believed in Welfare to work and was a very aggressive in moving people into jobs including it to city jobs. As the city's economy expanded and the employment in New York City grew, a good chunk of those people were actually Welfare people on Welfare who moved into city jobs.

Seth Barron: By Welfare we're talking about cash assistance?

Steven Malanga: Yes. We're talking about the classic cash assistance absolutely. And that was for years. The fundamental change in Welfare that began in the '60s and migrated into the '70s and '80s was people were allowed to stay on Welfare permanently almost for their entire lives without having to do anything forward or they could, for instance, prolonged Welfare by just doing things like taking job training, even if it never led to your job.

What Giuliani did is number one, he said, if you're able bodied, you need to work and you can't satisfy your Welfare requirement just by taking job training for instance. You have to get somewhere with that and you have to stay in working. And the other thing that Giuliani did, which Bloomberg also did, and actually I probably increased was oversight over Welfare eligibility.

Many of the people in New York City who were on welfare turned out, were not eligible and that this had begun really in the late sixties, when the city essentially stopped certifying or verifying whether people were on Welfare. That was thought to be, I don't know, too aggressive enforcement. Giuliani brought enforcement back and frankly, just sending out letters to people saying you have to come down and visit your office and tell us you are who you say you are.

Suddenly people just started disappearing from the Welfare rolls and Bloomberg continued that also saying we want to make sure this program goes to the people who are eligible for it. And the same thing with Medicaid. So that also continued to reduce the rules in New York City.

Seth Barron: What about his use of government to support, or his social agenda? People go on about the sodas.

Steven Malanga: So I think so. First of all, you're right. And this is where he got the reputation as running a nanny state. In particular, he's very interested in, I guess, people's personal health. And he made a commitment. He believes that you can use government to change people's personal habits. And part of this is a fundamental migration or evolution in the whole idea of what constitutes public health.

Public health policy goes back really to the 19th century when governments started doing things like installing sewers in order to end outbreaks of infectious diseases. And that was considered public health for a long time. In the 20th century and in the late 20th century in particular, public health medicine became much more aggressive in ways that are questionable.

But maybe the classic case is government recommending what kind of a diet you should have, which has turned out to be extremely controversial because there's really no settled science on that at this particular point. Bloomberg though believed that you could change people's habits. And so he had a ban on big gulps and he required a large chain restaurants to put the calories next to their menus to show.

Now of this, no research has ever shown that this has any kind of an effect. And over Bloomberg's term things like that you would, I guess, measure like the incidents of diabetes and the overall, let's say, average way to New York. Those things didn't really change significantly during that period of time.

The larger issue with all of this though is that he does believe, I guess you could say, more largely in the idea of government regulation. And even if you were to extend this to an area that I think is more significant and more troubling though it doesn't get as much publicity, is his regulation of business, particularly small business in New York. Bloomberg administration could be pretty aggressive in fines and fees on small businesses.

And even things like storefront designs, enforcing storefront design throughout the city route and that was quite controversial. And the reason I think that's generally significant is a president does have tremendous regulatory powers just through executive orders these days. Presidents now enforce a lot of their will, if you will, or a lot of their agenda, not necessarily through Congress, but through executive orders and in particular, that's the way the regulatory state has grown. And so for a mayor who believes that government can change people's habits, I think that might be a significant way that he would exercise his authority. And again, there are a lot of, one of the things we... I mean, New York is an interesting example because there are a lot of unintended consequences when government tries to do that.

I think probably the most interesting one is Bloomberg was a former smoker and he's a very much spent a lot of money on anti-smoking campaigns around the world through his foundation. In New York City he raised taxes on... New York State already has the highest taxes on packs of cigarettes in the country. He raised them in New York City, even high or like $1.20 higher than the New York State level. One of the things that's resulted in is New York State has the largest by far underground market for cigarettes in the country. And the famous or infamous Eric Gardner case where the confrontation between someone who was selling cigarettes illegally and the police department, which was periodically sent out to enforce the law against the underground marketplace in order to give some force to the cigarette, the higher cigarette taxes.

I mean, that results that of course in the confrontation and Gardner lost his life. And it was a tremendous controversy that went on for years. It's helped to, I think, undermine some of the confidence in the police department, in minority communities. But underlying all of that was this idea that the regulatory state has to be enforced in some way. And that was kind of like a flashpoint.

Seth Barron: Well, it looks like we've got a budding authoritarian. Steve, Thanks so much for joining us today. We'd love to hear your comments about today's episode on Twitter @CityJournal #10Blocks. If you like our show and want to hear more of it, please leave ratings and reviews on iTunes. This is your host, Seth Barron. Thank you, Steve, for joining us.

Steven Malanga: You're welcome.

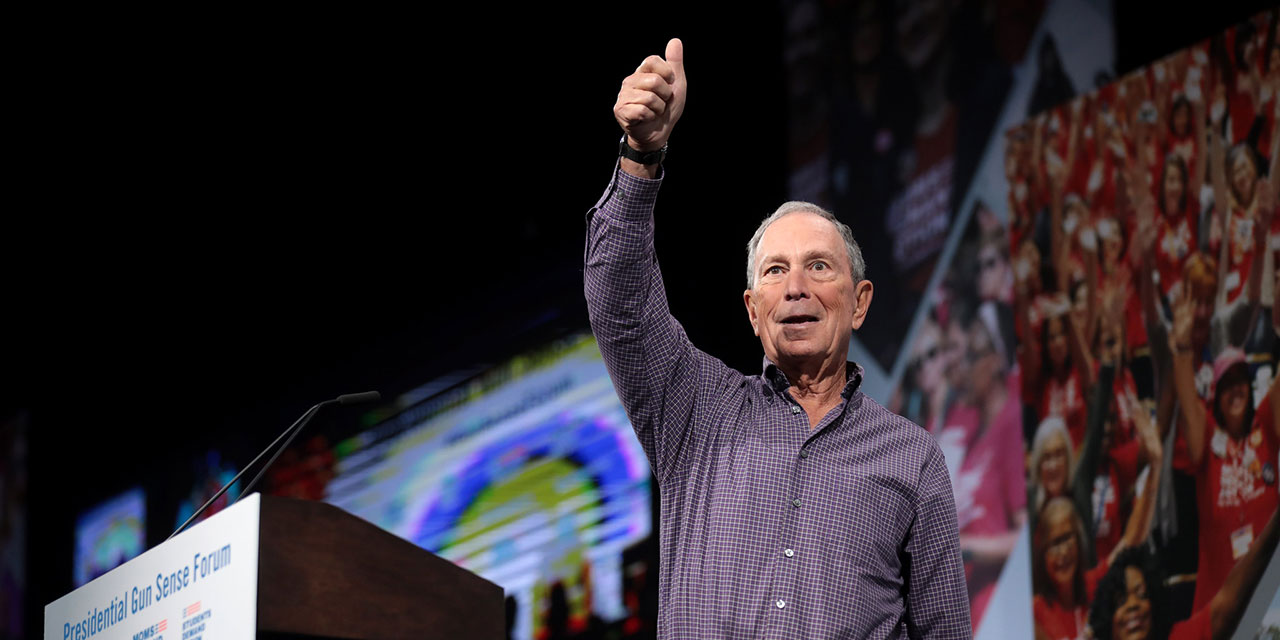

Photo by Gage Skidmore/Flickr