As a young attorney, in the mid-1990s, I helped defend the constitutionality of the nation’s first modern voucher programs. Back then, we were fighting to preserve two programs that served a few thousand kids in Milwaukee and Cleveland. Both were means-tested, limited to the poorest students, and animated by what Howard Fuller called the “rescue mission” justification for parental choice in education—that is, the imperative of empowering disadvantaged kids to exit failing public schools—rather than by what he deemed “a fight for broad societal change.”

While the rescue-mission rationale dominated the parental choice movement for decades, it has never been the only one. In his 1955 essay, “The Role of Government in Education,” Milton Friedman argued that vouchers could reform the entire education system by subjecting monopolistic public schools to competition. Education researchers Terry Moe and John Chubb argued in 1990 that choice was “a panacea,” which, “all by itself,” could “bring about the kind of transformation that, for years, reformers have been seeking to engineer in myriad other ways.” And Lisa Graham Keegan, who served as Arizona’s education secretary from 1995 to 2001, claimed that “backpack funding”—allowing kids to carry, in a metaphorical backpack, the public dollars allocated for their education, which their parents could spend on the educational option of their choice—could reduce the inefficiencies in our Rube Goldberg–like schooling system.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Until recently, many in the parental choice movement remained committed to incremental, means-tested reforms that promised to rescue disadvantaged kids from failing public schools. They avoided (and questioned) the argument that giving parents—all parents—control over their children’s education could reshape America’s K-12 education system.

Admittedly, I was among them. I embraced the rescue-mission goal as a moral imperative (and still do). But I doubted whether universal backpack funding was politically possible—and even if it were, whether it could achieve system-wide reform.

The time has come to admit that, on the second and third counts, I misunderstood both the politics and power of universal choice.

Since 2020, 15 states have extended choice programs to all families, regardless of income. Most of the new universal-eligibility programs have used a funding mechanism—education savings accounts (ESAs)—that allocates public funds for kids’ education in flexible-use spending accounts controlled by parents.

ESAs allow parents to subdivide these funds among numerous educational providers to cover the costs of private school tuition, tutoring, educational technology, curricula, books, and more. In other words, these accounts not only allow families to choose among schools but also enable them to customize their kids’ education.

The rise of ESAs means that backpack funding is now the reality in many states—and it is changing education systems, in real time.

Consider some data. In 2024, the number of students participating in a private-school-choice program surpassed 1 million for the first time. One year later, the number had increased by more than 25 percent, to 1.3 million. Some states have seen participation double year over year; many have seen demand exceed capacity caps. Participation is likely to grow exponentially in years to come as new programs—including Texas’s universal ESA initiative and the first-ever federal tax credit to encourage school choice—come on line and existing programs continue to expand.

Families that participate in parental choice programs typically don’t look back. For example, a recent study of Arkansas’s Education Freedom Account initiative found a 90 percent year-over-year retention rate, with the number of participating students doubling from the first to second year. Other states have observed similar trends.

Expanding choice programs increases not only the demand for parental choice but also the supply of alternatives to traditional public education. The rise of learning pods, microschools, and homeschooling co-ops—all enabled by ESAs—proves that parents and providers are capable of creating effective alternatives to district schools.

No state has demonstrated the transformative power of universal parental choice more clearly than Florida. The Sunshine State has the largest number of students participating in parental choice programs (over 500,000). Doug Tuthill, the former president of Step Up for Students, which administers Florida’s ESA program, told me that customization is transforming education in the state. Rising demand, fueled by families’ control of over $4 billion in public education funds, per Tuthill, is driving new supply. The state’s ESA program has allowed former public school teachers to create innovative options, such as microschools, that better serve students.

Perhaps most remarkably, rather than complain about lost funding, Florida public school districts are active participants in the state’s vibrant choice market. The state’s public schools have leased underutilized space to microschools and learning pods and offered unbundled courses and other educational services to ESA participants. According to Tuthill, 37 of the 67 state’s public school districts are now registered with Step Up for Students as ESA service providers, with 11 more seeking to participate.

In 2005, not long before he died, Milton Friedman predicted: “Sooner or later there will be a breakthrough; we shall get a universal voucher plan in one or more states. When we do, a competitive private educational market serving parents . . . will demonstrate how it can revolutionize schooling.” States with universal choice are proving him right.

Choice is not a magic bullet. The success of choice programs is not guaranteed, and many obstacles remain, including legal challenges to new programs, administrative difficulties with ESAs, and opponents who continue to attack choice initiatives and threaten providers’ autonomy. Addressing and overcoming these obstacles will take time, effort, and money—but it’s all a small price to pay for an education system that truly puts students and families first.

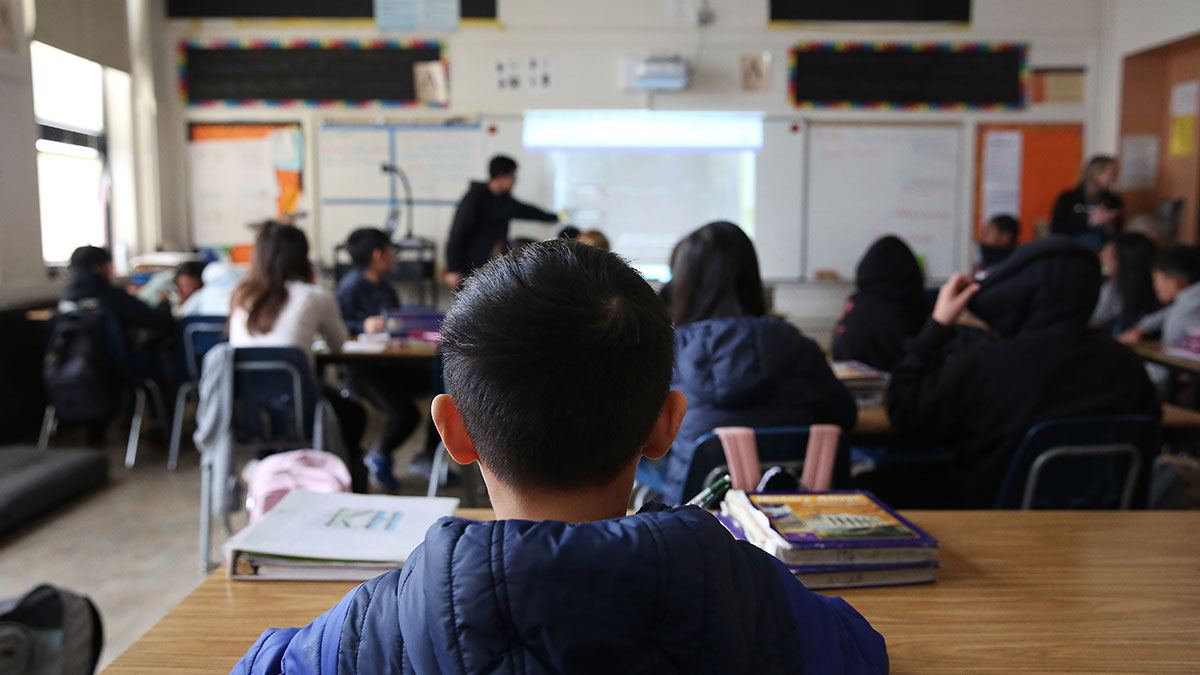

Photo By Lea Suzuki/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images