Jane Jacobs once declared: “Downtown is for people.” As Fred Siegel saw it, cities were for the middle class. Siegel, who died this past May at 78, had wide-ranging interests, but his anchoring themes were urbanism and bourgeois values. For Siegel, cities should not, and need not, devolve into communities controlled by the very rich and very poor. Resisting that outcome was his life’s work.

Many self-styled proponents of “families” and “the middle class” populate the urban scene these days. But in progressive parlance, those terms rarely mean more than redistributionism. The defining values of Siegel’s bourgeois urbanism were government that works, public safety, and responsibility. Like many intellectuals who began on the left and wound up on the right, Siegel was voluble on the Democratic Party’s failings. But he also has much to teach political conservatives who have given up on cities and believe that everything is always downhill in modern America. That belief is belied by New York City’s renaissance starting in the mid-1990s. Siegel was its leading chronicler.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The term “New York intellectual,” to the uninformed, carries overtones of coastal elitism. Traditionally, though, it had a specific meaning: someone erudite, combative, and from a working-class Jewish background. A New York intellectual “argued the world” by dint of his being interested in everything—culture, history, politics—and his relentless civic engagement. He cultivated a confrontational style through literally face-to-face modes of argumentation that, in the era of snarky online exchanges, have become rarer. The New York intellectual prided himself on his candor and his groundedness. Fred Siegel, who embodied these qualities, was one of the last of the New York intellectuals.

Bronx-born, Siegel grew up in a family that was decidedly progressive, if not radically so. His maternal grandfather, Harry Fein, was a vice president in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and friend of that organization’s famous leader, David Dubinsky. His grandfather was one of Siegel’s heroes growing up, the other being his father, a D-day veteran who worked as a plant manager for Revlon. In terms of their political principles, Siegel saw his grandfather and father as defined by their support for Israel and anti-Communism. They were “social democrats.”

The family moved around, living in military housing at Fort Tilden, the Jacob Riis Houses on the Lower East Side, and eventually settling in Westfield, New Jersey. Siegel graduated from Passaic Valley Regional High School and studied at Rutgers and the University of Pittsburgh. Trained as an economic historian, he did his first serious research on the antebellum South. During later years, this choice of specialty struck many in his circles as almost comically arcane. But this early work on the South (published in book form in 1987) is relevant to his more famous work on cities. As Siegel’s former colleague, historian Peter Buckley, pointed out, it explores the question: Why do some communities decline, while others thrive? Danville, Virginia, Siegel argued, was fated by soil and climate to overreliance on the tobacco industry, which, in turn, fated it to a diminished urbanity. Danville’s population was “served by fewer roads, had fewer newspapers, magazines, and radios, and suffered from less in the way of health and medical care.” Over time, Siegel would become less determinist. New York City, at its lowest points, was another community widely considered fated to stagnate. Siegel rejected that. In fact, his argument for municipal responsibility—that modern cities are masters of their fates—would be one of his signal contributions.

Siegel worked as a college professor mainly at Cooper Union, where he served on the faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. But he never wanted to be confined by academia. While pursuing an academic career, he edited Dissent, working under Irving Howe, the Platonic ideal of the New York intellectual. Howe was also a literary critic and instrumental in the founding of the Democratic Socialists of America. Siegel would break with Dissent over its unresponsiveness to crime but retain a lifelong admiration for Howe and had many friendships across the political spectrum. One was with labor historian Leon Fink. “We were happy combatants for many years,” Fink remembers. Strangely, by contemporary standards, Siegel maintained his cross-partisan friendships by leaning into politics instead of ignoring them. “It was hard to separate his personality from his politics,” Fink said, “because political discussion was always part of his friendship.”

Siegel’s engagement with New York deepened as the city’s decline became more acute. Its problems were, first, ungovernability (Siegel heard, in person, the West Side Highway collapse of 1973) and, second, a growing indifference, shading into hostility, toward middle-class values. He was fond of illustrating this second point through the example of Jack’s Pastrami King, a Williamsburg eatery, avidly patronized by Jews and Puerto Ricans alike, that the 1977 blackout riots put out of business. At this time in New York history, architectural critics were questioning how a city that claimed to be a world center for high culture could have permitted the demolition of old Penn Station. Siegel questioned how a city that claimed to affirm the American dream could have accepted the demise of such an obviously wholesome establishment as Jack’s Pastrami King.

This was how Fred Siegel worked: begin with observation, then proceed, through a searching analysis, to determine why others insist on dismissing the reality you see before you. How, for instance, could someone’s judgment become so clouded as to be convinced that riots were good? For Siegel, the answer had to go back to ideology and, in particular, to liberalism, which dominated New York governance. He voted for David Dinkins in 1989 but quickly became disillusioned with that mayoral administration and the liberal establishment backing it. During the New Deal, all the intellectual energy surrounded men of action and ideas, such as President Franklin Roosevelt and New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Those liberals displayed, in Siegel’s view, an admirable adaptability, spirit of innovation, and capacity for self-evaluation. The 1980s liberal establishment, by contrast, was marked by self-absorption and detachment. Siegel wrote in his 2005 book The Prince of the City, his comprehensive account of Rudy Giuliani’s mayoralty: “The widely accepted assumption of ungovernability meant mayors were largely unaccountable. And if the city was ungovernable through no fault of its own, there was no reason to challenge the suppositions behind New York’s self-evidently virtuous political culture of compassionate liberalism. New York’s problem, it seemed, was that it was too good, too compassionate for the rest of America, and the city could only hope that some day the rest of the country would rise to its moral level.”

In the loud debate over New York’s decline, Siegel stood out for his skill at diagnosing the ideological roots of the problem, as well as for his pragmatism. His thought always had a practical turn. It went back to his penchant for close observation, which, for him, had a way of breeding optimism. As his son Harry Siegel explains: “This discourse that fetishized failure—it just didn’t capture the reality of New York City. He knew it was untrue because he lived here. He was very practical-minded, and you couldn’t pass that one over on him. It was not as hopeless as it was made out to be.” Siegel was thus perfectly positioned to advise Giuliani on his successful 1993 mayoral run.

At the same time, Siegel also drew the attention of the national Democratic Party. In the early 1990s, having lost three straight presidential elections, Democrats were in the mood for retrenchment. Siegel found a receptive audience for his analysis of urban decline in the Democratic Leadership Council, a centrist organization that would shape Bill Clinton’s agenda. As Will Marshall, head of the Progressive Policy Institute, the Democratic Leadership Council’s policy arm, put it, Siegel uniquely grasped the notion of cities “as a microcosm of liberalism’s worst pathologies.” Siegel was affiliated simultaneously with the Manhattan Institute and PPI because, as his wife, Jan Rosenberg, explains, “He would always say he would talk to whoever would listen, and they both listened.”

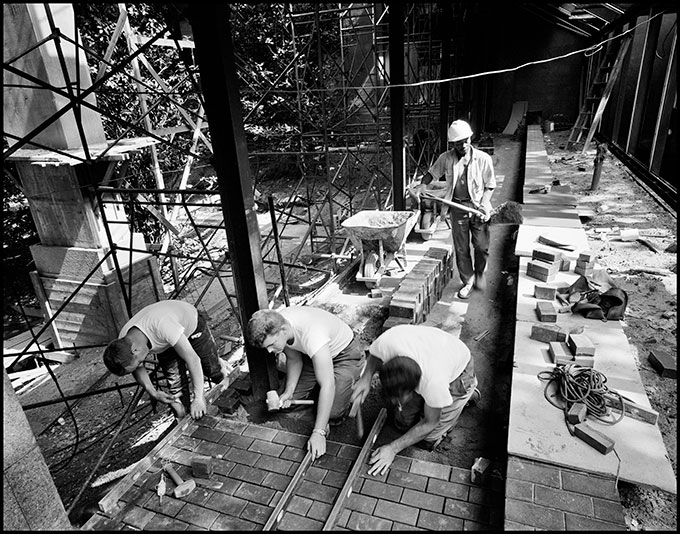

Siegel gave energy and shape to reforms whose success proved almost disorienting. Crime and welfare rolls declined at rates above the predictions of even ardent proponents. Jobs and population rebounded. New York and other cities became centers of policy entrepreneurialism, pushing innovations such as charter schools. The miasma of urban fatalism lifted, and the future happened again. And all this because, at a time of doubt, Siegel and others kept their faith in the possibility of functional government. Conservative writer Steven Hayward explains: “I don’t think he ever shed entirely his social democratic sympathies. Like [Nathan] Glazer and [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan, he supported a welfare state that worked. What he really hated above all was intellectual dishonesty—refusal to acknowledge that some programs don’t work.”

Siegel devoted his later decades to defending the reforms behind New York’s comeback, frequently in the pages of City Journal, where he was a longtime contributor and an early editor. He served as an advisor on the 2023 film Gotham: The Rise and Fall of New York. In 2010, he took a position as scholar in residence at St. Francis College, a working-class Catholic school in Brooklyn. Bringing Siegel to the campus, Chancellor Frank Macchiarola reasoned that, as son Harry recalls, “This will be a smarter and more interesting place with Fred Siegel around.”

Siegel also gained the reputation as a prophet of populism. For decades before the 2016 election, he had been focused on the shakiness of a political system unresponsive to middle-class concerns. His 2013 book The Revolt Against the Masses, a work of intellectual history, examined the elitist temptation of American democracy. Siegel believed that it was wrong to see New York–style liberalism as a straightforward case of mission creep from the New Deal. He saw the New Deal era as basically sound, an interregnum in the modern Left’s development. The true spiritual antecedents of 1960s leftists were the “aristocratic” liberals of the earlier twentieth century, figures such as Herbert Croly and H. G. Wells. These men sought a restoration of traditional hierarchies against “mass” everything—mass culture, mass production, and, most of all, mass democracy. Liberals’ century-old demands for more deference to elites discounted American democracy’s native capacities. Son Jacob Siegel, an editor and writer at Tablet, explained: “The indissoluble connection between democracy and a healthy middle class—that was the through line [in all Siegel’s thinking]. And also that they were not the hollow men, they were not lesser, inferior characters. America didn’t need an aristocracy to be noble. . . . He was always turned off by the épater le bourgeois stuff.” Consequently, America’s resurgent populist moment caught Fred Siegel less off guard than most.

John Lindsay, New York’s blue-blooded mayor from 1966 to 1973, cast a long shadow over Siegel’s political imagination. Siegel saw Lindsay as a nationally significant figure for pioneering the “upstairs-downstairs” political model. Lindsay forged a coalition between Park Avenue elites and New York’s ever-swelling low-income population and set it against New York’s working class. The Lindsay administration, under which crime and dependency rose, the local economy cratered, and the city budget careened into insolvency, has been subject to many criticisms. Siegel’s critique of Lindsay, powerfully developed in his 1997 book on America’s urban crisis, The Future Once Happened Here, was distinctive in its political focus. If, to win elections, city politicians no longer needed the working class but also actively campaigned against it, what did that mean for the future of urban democracy?

Siegel’s best-known concept—what he called the “riot ideology”—emerged from his analysis of Lindsay. Lindsay left a legacy of violence, not only in the sense of 1,000-plus murders per year but also through his sanctioning the threat of rioting as a legitimate political tactic. Lindsay claimed to be a great statesman because he had spared New York the apocalyptic mayhem that other cities endured during the “long, hot summers” of the 1960s. Siegel saw this claim as misleading. He argued that the extravagance of Lindsay’s giveaways could be understood only as a means of paying off those threatening to give New York the Watts treatment.

Indeed, this was the essence of the riot ideology: a political process directed by intimidation. The 1960s taught that any interest group that wanted something from government should riot for it or threaten to do so. The riot ideology may be seen anywhere that protesters brandish signs saying, “No justice, no peace” (a slogan closely associated with Al Sharpton). The riot ideology helps explain why we have never seen an end to urban “unrest.” Savvy practitioners of urban politics learned from Lindsay’s example and those of other 1960s liberals that not only should you never let a crisis go to waste—you should manufacture crises as a means of achieving your broader policy ends. Redistribution is not the only possible payoff. The best contemporary example of the riot ideology is the embrace, by mainstream politicians, of previously extremist public-safety ideas such as jail abolitionism and defunding the police. The riot ideology helps account for why the “community-based” social programs favored by activists face scant oversight, despite chronic problems with corruption.

The riot ideology also helps explain why the upstairs-downstairs model fails, and on its own terms. Instead of containing the forces that it purports to master, it becomes captive to them and ends up nurturing them. “The virtue of disruption, academics and observers argue, is that it gives African-Americans a crisis with which to bargain,” Siegel wrote. “But after 50 years, what has this bargain achieved, except to cultivate a community that excels in resentment?”

When Lindsay-style leaders fail to deliver in terms of material outcomes (less crime and/or poverty), they must redefine success by intentions and “gestural” compassion. One such leader was Barack Obama. Siegel drew a straight line between Lindsay and Obama, who built a similar coalition and, after eight years in the White House, left race relations in a worse state than when he entered. Always, though, Obama remained enamored of his own virtue and the tragic gap between it and “the world as it is.” (The Lindsay-Obama parallels are drawn out most richly in The Crisis of Liberalism, Siegel’s final book.)

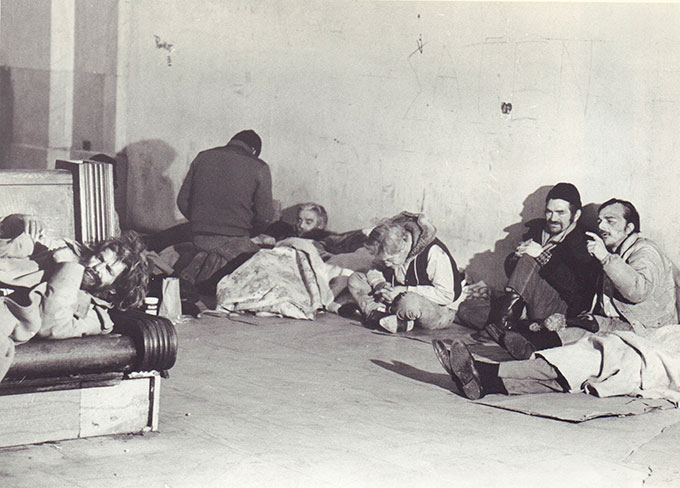

Upstairs-downstairs dynamics help explain cities’ persistent failings on homelessness, the subject of Siegel’s City Journal essay “Reclaiming Our Public Spaces” (Spring 1992). Grand public spaces show urban democracy at its best. But by the early 1990s, two groups had come to dominate them: the street homeless and the professional advocates, who largely hail from the upper middle class. Public disorder benefits the advocacy crowd, satisfying its desire for recognition, and it benefits the street homeless, who retain continued and unqualified access to parks and plazas. The middle class gets nothing. This disgraceful state of affairs, concern over which now tops public opinion surveys across the nation, was best anatomized 30 years ago by Fred Siegel. As recently as 2021, the Manhattan Institute’s communications team was fielding queries from local leaders across the nation about his 1992 essay.

Siegel’s conception of dependency was striking in its expansiveness. He saw the dependency agenda as harmful to individuals, politics, and cities. “Dependent individualism” was his term for urban liberals’ great “gamble” on statism and “moral deregulation,” which, in practice, meant “an extraordinary transfer of responsibility from the family to the state.” The transfer, Siegel showed, “produced the worst of both worlds: fiscal failure and further family breakdown.”

The dependency agenda was further harmful in how it translated into a politics of “extraction.” There can’t be a truly civic debate when one side is debating principles and the other is debating interests—that is, how much can be squeezed out of government. Welfare-rights groups were one notable practitioner of the politics of extraction. Others were riot ideologists and government unions. Siegel may have come from a labor background—but the garment workers’ union was private. By contrast, today’s modern labor paradigm is defined by government unions, a model based on political power and uninterested in the economic growth that would benefit the broader city. An unchecked dependency agenda changed urban politics from an exercise in self-government into a raw power struggle over who gets a bigger share of a city’s shrinking resources.

Worst of all were dependency’s implications for urban governance. By the late 1980s, mayors had developed a bad habit of preaching what they practiced when it came to the dependency agenda. Cities, they implored everyone to understand, were the greatest victims. Mayors attributed every social problem to inadequate state and federal aid. Siegel denounced “Tin Cup Urbanism,” a phrase coined by Milwaukee’s former reformist mayor John Norquist. Siegel was heartened when Mayor Giuliani voiced skepticism to the state legislature in Albany that more money would benefit the city’s Department of Education, given that agency’s dysfunction. New York’s shift away from municipal dependency to a firmer sense of municipal responsibility, which persisted through the Michael Bloomberg years that followed Giuliani’s mayoralty, was, in its way, as dramatic as the declines in crime and welfare.

The prospects of bourgeois urbanism are uncertain. Schools in the suburbs remain better than those in the urban core; there’s a profound lack of affordable housing in leading cities, especially for families; and after a generation of urban flourishing, public disorder has become an urban plague again. Those few New York politicians who may sincerely be said to represent the middle class have no path to winning citywide office.

For at least three reasons, Fred Siegel’s work will remain relevant. The first is the “Groundhog Day” character of policy debate. When finding themselves arguing over ostensibly settled questions, such as the “root causes” of crime, many now feel as though they have woken back up in 1968. The good news is that answers to all the old urban questions are at hand, many furnished by Siegel. Anyone who wonders why spending on homelessness never seems to reduce homelessness should consult, in The Future Once Happened Here, his discussions of how Great Society theorists openly envisioned social programs to function like a permanent Works Progress Administration. Anyone stunned by the contention that Covid-related learning loss is a subjective concept, since mastery of math and reading is a middle-class fetish, should read Siegel’s third chapter in that book, on the “Ocean Hill–Brownsville Kulturkampf.” Anyone feeling diminished pride in bourgeois democracy should read the sections in The Revolt Against the Masses about our nation’s considerable cultural attainments during the much-maligned postwar “Organization Man” period. Anyone charmed by Al Sharpton in his current instantiation as a colorful rogue should consult The Prince of the City, with its overview of the violent race-baiting episodes to which he owes his fame. Anyone nostalgic for the WASP aristocracy should read Siegel on John Lindsay.

Second is the ongoing problem of immigration and integration. Siegel never stopped pondering why integration was more successful in the case of Ellis Island than in the case of blacks’ Great Migration. He was open to the idea that some sort of special accommodation had to be made for the Great Migrators. But he rejected the idea, fashionable during the Great Society, that assimilation was an unjust expectation, because this amounted to an implicit rejection of the bourgeois order. The 1960s-era debate over integration and cities bears on the current debate over immigration, and immigration is one reason that we can’t give up on bourgeois urbanism. America’s character as a migrant nation assigns high importance to cities because of immigrants’ tendency to concentrate there. In this respect, the American future will hinge on urban policy.

Third, as intimated by The Prince of the City’s subtitle—Giuliani, New York and the Genius of American Life—Siegel saw middle-class values as universal. His bourgeois urbanism was no tribalist variant. In democratic America, the common good could be defined only by what benefits middle-class families—“One City, One Standard,” as Mayor Giuliani put it. The shaping of policies about housing, crime, the budget, and schools must still proceed along bourgeois lines, as no other viable model for civic health exists. Cities’ disposition to reckon honestly with failure remains rare. Cities’ governability is, once again, in question. The possibility of urban revival, however, is not. Fred Siegel wrote the blueprint for it.

Top Photo: Fred Siegel (COURTESY OF THE MANHATTAN INSTITUTE)