Should debt-ridden and economically struggling Western governments be doing everything possible to reduce their deficits? The debate over that question has become increasingly confusing—not only in Europe, where the matter is particularly urgent, but in the United States, too. Those in favor of immediate deficit reduction argue that it is a necessary precondition of economic growth. Today’s deficits become tomorrow’s debt, they say, and too much debt can bring fiscal crises, including government defaults. Markets, worried about solvency, will require high interest rates on government bonds, making it more costly for countries to service their debts. Defaults could cause banks holding government bonds to collapse, possibly leading to another financial meltdown. There can be no sustained growth, say the deficit hawks, unless we start balancing our books.

Their opponents agree that we should eventually rein in deficits—but right now, when economies worldwide are weak, is the wrong time. To shrink a deficit, this argument goes, you need to raise taxes or to cut spending. Taking either of those steps reduces aggregate demand, making an already faltering economy sputter and sink into serious recession. The all-important debt-to-GDP ratio swells because GDP growth slows more than the measures taken reduce debt. Therefore the approach is self-defeating. Governments should instead continue to run deficits and paper them over with borrowed money, waiting to balance their budgets until economies get stronger.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The deficit debate is often misleading, however, because it tends to ignore a huge difference between the two kinds of deficit reduction. The evidence speaks loud and clear: when governments reduce deficits by raising taxes, they are indeed likely to witness deep, prolonged recessions. But when governments attack deficits by cutting spending, the results are very different.

In 2011, the International Monetary Fund identified episodes from 1980 to 2005 in which 17 developed countries had aggressively reduced deficits. The IMF classified each episode as either “expenditure-based” or “tax-based,” depending on whether the government had mainly cut spending or hiked taxes. When Carlo Favero, Francesco Giavazzi, and I studied the results, it turned out that the two kinds of deficit reduction had starkly different effects: cutting spending resulted in very small, short-lived—if any—recessions, and raising taxes resulted in prolonged recessions.

We weren’t the first people to distinguish between the two kinds of deficit-cutting, of course. In the past, such critics as Paul Krugman, Christina Romer, and some economists at the IMF have responded that the two approaches don’t have different results. When an economy performs well after government spending cuts, they say, it’s actually because the business cycle has picked up, or else because the government’s monetary policy happened to be more expansionary at the time. But my colleagues and I took both factors into account in our research, carefully analyzing the business cycle and monetary policy in relation to each fiscal episode, and concluded that the difference between expenditure-based and tax-based actions remained.

The obvious economic challenge to our contention is: What keeps an economy from slumping when government spending, a major component of aggregate demand, goes down? That is, if the economy doesn’t enter recession, some other component of aggregate demand must necessarily be rising to make up for the reduced government spending—and what is it? The answer: private investment. Our research found that private-sector capital accumulation rose after the spending-cut deficit reductions, with firms investing more in productive activities—for example, buying machinery and opening new plants. After the tax-hike deficit reductions, capital accumulation dropped.

The reason may involve business confidence, which, we found, plummeted during the tax-based adjustments and rose (or at least didn’t fall) during the expenditure-based ones. When governments cut spending, they may signal that tax rates won’t have to rise in the future, thus spurring investors (and possibly consumers) to be more active. Our findings on business confidence are consistent with the broader argument that American firms, though profitable, aren’t investing or hiring as much as they might right now because they’re uncertain about future fiscal policy, taxation, and regulation.

But there’s a second reason that private investment rises when governments cut spending: the cuts are often just part of a larger reform package that includes other pro-growth measures. In another study, Silvia Ardagna and I showed that the deficit reductions that successfully lower debt-to-GDP ratios without sparking recessions are those that combine spending reductions with such measures as deregulation, the liberalization of labor markets (including, in some cases, explicit agreement with unions for more moderate wages), and tax reforms that increase labor participation.

Let’s be clear: this body of evidence doesn’t mean that cutting government spending always leads to economic booms. Rather, it shows that spending cuts are much less costly for the economy than tax hikes and that a carefully designed deficit-reduction plan, based on spending cuts and pro-growth policies, may completely eliminate the output loss that you’d expect from such cuts. Tax-based deficit reduction, by contrast, is always recessionary.

With this evidence in hand, let’s go back to the two views with which we started. People who support deficit reductions are correct, so long as those reductions are accomplished by cutting spending and, ideally, accompanied by other pro-growth policies. The broader idea that any deficit reduction is beneficial—that all you need in order to calm a market is a smaller deficit—is simplistic.

The opposite idea—that any immediate deficit reduction will slow the economy and prove self-defeating—is equally simplistic. A deficit-reduction program of carefully designed spending cuts can reduce debt without killing growth, so there’s no need to be so protective even of today’s weak economies. But the deficit doves are right to be wary of tax-hiking deficit reductions, as Italy, which has struggled with a high debt-to-GDP ratio for the last 20 years, demonstrates. Various Italian governments have repeatedly tried to reduce that ratio by raising more revenue, a course that has crippled the Italian economy and left the ratio firmly in place, just as the deficit doves would predict. Last November, Italy’s current government passed a very large tax hike; the country’s economy promptly nose-dived and is expected to show negative 2.6 percent growth for 2012. (Italy is finally starting to realize its errors: it has initiated a “spending review,” which should lead to spending cuts in the near future, and passed labor-market reforms.)

The deficit hawks are right about something else: America urgently needs to reduce its national debt. Recent work by economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff shows convincingly that when debt reaches about 90 percent of GDP, it becomes a burden on growth. Today, America’s debt is almost 80 percent of GDP—a number that’s on track to reach 120 percent in the not-too-distant future, thanks to health-care spending, Medicare in particular.

In Europe, where debt-to-GDP ratios are even higher than in America, deficit reduction is still more pressing. If Greece, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, and Italy do nothing about their finances, they run the risk of defaulting on their debt—a disastrous event not just for them but for the euro, which would implode, and thus for the global economy. They certainly won’t be able to borrow at reasonable rates without some kind of fiscal adjustment. Sure, you can debate how much the European Central Bank should help these countries, but clearly they have to do something to put their own houses in order. Raising taxes and depressing growth isn’t the answer; cutting spending is.

For the time being, markets seem to trust the United States, and Treasury bonds are still in demand, which lets us borrow cheaply. But we have to fix our debt trajectory soon. The idea that everything will be fine without fiscal adjustments isn’t merely wishful thinking; it’s an abandonment of our children, who will have to bear a crushing fiscal burden. The longer we wait, the higher the cost of fixing the problem will be.

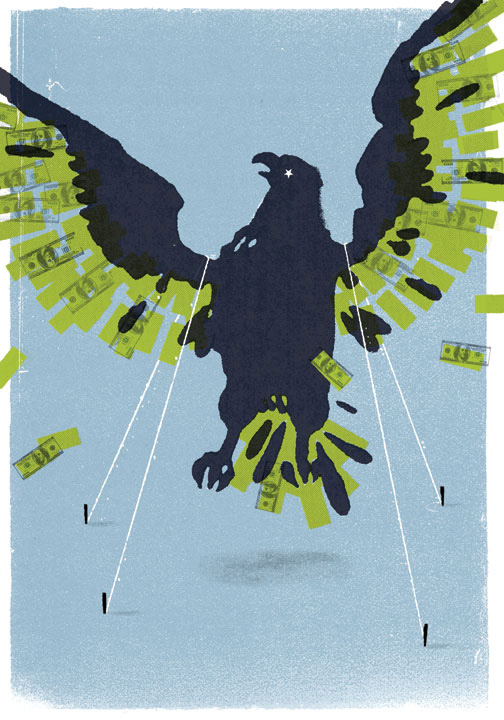

Cutting spending isn’t easy, of course, because the recipients of government subsidies and benefits—public employees, early retirees, large companies getting expensive favors, local governments with no fiscal discipline, and on and on—are well represented in the political arena, while taxpayers are not. Nevertheless, the conventional wisdom that fiscally prudent governments will invariably suffer electoral losses seems to be wrong. In a recent paper, Dorian Carloni, Giampaolo Lecce, and I show that even governments that have drastically slashed spending haven’t systematically lost office in the elections that followed. Sometimes—though not always—voters do understand the need to retrench, rewarding governments that ignore the lobbies’ pleas, especially when those governments speak clearly to voters and are fair in how they cut spending.

But if we cut spending, do we necessarily hurt the poor? Not in such countries as Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy, whose public sectors are so inefficient and wasteful that they can certainly spend less without affecting basic services. Even in countries with better-functioning public sectors—such as France, where public spending is nearly 60 percent of GDP—there’s a lot of room to economize without hurting the poorest and most vulnerable. And even in America, public spending is about 43 percent of GDP, a level common in Europe not long ago, and up from 34 percent in 2000. Western governments can save money and avoid inflicting injury by improving the way welfare programs are targeted; scaling back programs, such as Medicare, that use taxes that were raised, in part, from the middle class to give public services right back to the middle class; and gradually raising the retirement age to 70. If the French think that they can keep retiring at 60, they’re kidding themselves.

Once we cut spending, the tax burden can lighten. The question then becomes how to distribute the reduced tax burden among taxpayers. Above all, does heavily taxing the wealthiest people harm economic growth? And if so, how much? Honest economists will confess that they aren’t sure. We aren’t even sure how much the rich currently pay, thanks to the complexity of tax systems like the American one. Every other day, it seems, you read what looks like a perfectly researched article in the New York Times showing that the rich pay proportionally less than the middle class does. The next day, what seems an equally rigorous article in the Wall Street Journal tells you that the United States has the most progressive tax system in the world.

My own view is that reducing the size of government is more important than protecting every dollar in the pockets of the wealthiest 1 percent. But however the resulting tax burden is distributed, the important thing is that we cut spending. Whoever wins the next presidential election in the United States will need to present a plan that changes the trajectory of the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio. It’s exceedingly important that he do it the right way.