Charles Murray’s 1984 book Losing Ground was the type of consequential study rarely seen anymore. Culminating in a radical “thought experiment” of eliminating the social safety net, it captured public attention, drew academic fire, laid the groundwork for the welfare reforms of the following decade, and launched a career in which Murray would provoke—and shape—debates over IQ, genetics, class, race, education, and more. As both welfare policy and racial disparities return to prominence in our political debate, it’s worth looking back on that career. A mix of preparation and happenstance catapulted him into the closest thing to superstardom to which a social scientist can aspire.

“The whole thing about Ronald Reagan ‘shredding the safety net’ had been a big deal,” Murray recently recalled from his home in Burkittsville, Maryland. The president had popularized the term “welfare queen” and tightened some welfare rules by signing a 1981 bill. And by that point, Murray had some informed thoughts about the safety net.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Then pushing 40, Murray had already lived quite a life. He hailed from Newton, Iowa, where his father was a Maytag executive—and where Murray had taken on identities both as a smart misfit who played chess by mail and as a pool-hall prankster in what he calls a “happy, uneventful childhood.” He’d earned a history degree from Harvard and a political science Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. And he’d spent years evaluating government programs.

Murray joined the Peace Corps after getting his B.A., heading to Thailand as a volunteer with the Village Health and Sanitation Project, which promoted modern sanitation to rural Thais. He worked for two years in that role and another four doing research on rural development. An insurgency was under way, and the Thai and U.S. governments were funding such work to win over the people. (“No, I was not a covert CIA agent,” Murray told me, referring to an allegation one finds online.) It was in Thailand that Murray learned how government can backfire, as well-meaning people wade into affairs they don’t understand and state-provided aid infantilizes formerly self-sufficient citizens.

It was also in Thailand that Murray first worked with the American Institutes for Research and his mentor Paul Schwarz, whose writing style he intentionally copied in his early years. After returning stateside and putting in his time at MIT, Murray again worked for Schwarz and AIR, this time studying U.S. programs and eventually becoming chief scientist of AIR’s Washington, D.C., office. Murray was sympathetic to those who tried to help the poor—but he kept finding that the programs didn’t work.

Murray soon tired of his AIR work. “I’m not sure anybody ever read the reports, and even if they did, they didn’t have any effect,” he says. He was also coming out of a guilt-ridden divorce from his first wife, with alimony and child-support obligations. But he decided to take a risk, quitting his job with a plan of doing some consulting and writing a book about the nature of happiness. When consulting didn’t work out as he hoped, he reached out to conservative think tanks, setting off a lucky series of events in the early 1980s.

Murray’s first success was an offer to write a monograph about welfare policy for the Heritage Foundation. In researching it, Murray became fascinated by how the decline of poverty had slowed after the introduction of Great Society programs, and he decided to “practice” writing an op-ed about it. He turned the result over to Heritage, expecting little to come of it. Weeks later, he was surprised when Schwarz—for whom he was still doing consulting work—congratulated him on appearing in the Wall Street Journal.

Between the monograph and the unexpectedly high-profile op-ed, Murray’s arguments reached the conservative intelligentsia, including Irving Kristol, then editing The Public Interest, and Joan Kennedy Taylor, then director of book publishing at the Manhattan Institute. The institute invited Murray to speak, raised a $30,000 advance against royalties for him to write a book on welfare, and promoted his ideas to lawmakers and media outlets. Murray would spend the better part of a decade as an MI senior fellow.

Losing Ground is the story of how things were supposed to improve after the 1960s but didn’t. Disadvantaged young women were having children out of wedlock, disadvantaged young men were dropping out of the labor force, crime was up, and education had gone to hell.

Reading the book today, one is struck by how far social science has come. Nowadays, poverty data are available at the click of a mouse; back then, Murray spent hours in the Library of Congress and the reading room at the Census Bureau’s facilities in Suitland, Maryland, often settling for less-than-ideal data. But the book is gripping, anyway, using a mix of graspable numbers and commonsense storytelling to make its point.

As Murray noticed, the official federal poverty rate fell markedly in the 1950s and 1960s, but progress faded in the 1970s. However, the official measure is an odd statistic; in determining how much money a person has to live on, it counts cash income, including welfare benefits, but excludes other sources of government aid like food stamps. So Murray also presented trends for “net” poverty, which includes those other sources of support, and “latent” poverty, which excludes government assistance entirely. Net poverty continued to decline after the safety net expanded, but latent poverty, which Murray labeled the “most damning statistic,” stalled—and even started rising. Poverty had fallen for two decades as the economy had grown, but that progress had ended, with any further “gained ground” coming from government transfers.

Murray’s narrative of how progress ended relies heavily on incentives. In rewriting welfare policy, society changed the rules for the poor. It now made sense, in the short term, to behave in ways that were self-destructive in the long term. He illustrated this vividly in the narrative of “Harold and Phyllis,” a fictional young couple. Phyllis is pregnant, neither plans to go to college, and their parents have little money. Murray explained the options that the couple would have confronted in 1960, and again in 1970. In 1960, welfare was unattractive; the benefits for single mothers were low, and “man in the house” rules would kick Phyllis off the program if the two lived together. But by 1970, welfare was more generous. Phyllis could support herself that way, if hardly lavishly; the two could live together without affecting her benefits, so long as they didn’t marry; and Harold might be able to work only sporadically if he didn’t enjoy his job.

“His ‘most ambitious thought experiment’ was to end welfare and let families and communities step in.”

Some aspects of the welfare system that Murray described were frustratingly wrongheaded. Before 1967, welfare mothers who got jobs were taxed at a rate of 100 percent, losing a dollar in benefits for every dollar they earned. That year, the government replaced this policy with the “thirty and a third” rule, meaning they could keep the first $30 they made and a third of the money they earned above that amount. As Murray notes, this change encouraged welfare recipients to work but made the dysfunctional program more attractive to those not already on it.

The ensuing furor over the book was messy. As Murray himself wrote in 1985, Losing Ground“ covers too much ground and makes too many speculative interpretations to lend itself to airtight proof.” Contemporaneous critiques tended to dispute that welfare had caused the social problems that Murray pinned on it, to credit welfare for alleviating more hardship than Murray acknowledged, and to quibble about how generous safety-net programs really were. Looking back, Murray told me that he’s still proud of the work, but he admitted that its focus on incentives came with some blind spots, including that “there was something in the nature of modernity that was pushing these phenomena of family breakdown over and above the welfare system.”

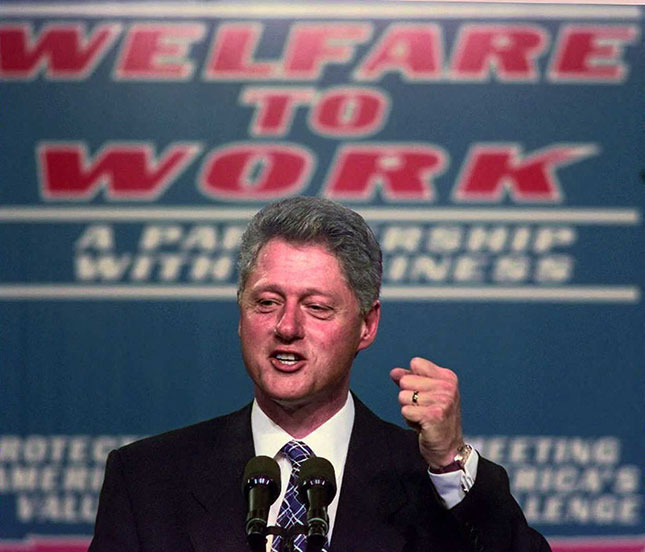

Of course, the United States never embraced Murray’s “most ambitious thought experiment,” which was to end welfare almost entirely and let families and communities step in. But within a decade, it was clear to most Americans that the welfare system was indeed highly dysfunctional, and states were experimenting with better ways of doing things. Congress passed some work-focused measures, most famously the 1996 welfare reform—essentially declaring that society would continue to help poor single mothers but that they would be expected to get jobs. Like Reagan’s “shredding” of the safety net, welfare reform didn’t stop the rise of federal social spending—at least, not for long. And like the expansion of welfare benefits discussed in Losing Ground, welfare reform inspired debate as to its effects. But single mothers worked more, and their poverty rate declined, after the laws changed. Welfare reform is considered one of the Right’s biggest policy successes in recent decades.

Murray eventually accepted the safety net. In 2006, he released In Our Hands, which proposed replacing government social programs with a direct payment to each adult: a “universal basic income,” or UBI. It was a concept he’d thought about since the late 1980s—inspired by the ideas of Milton Friedman, his growing awareness of the fact that people are born with different abilities, and his dislike of meddlesome government—but that he didn’t think the United States could afford until federal spending ballooned to its more recent levels. Murray was therefore an early adopter of an idea that has attracted interest across the political spectrum.

Murray’s writings echo in welfare debates to this day. As President Joe Biden has pushed to expand the safety net through his Build Back Better plan, for example, conservative critics have highlighted the unwelcome incentives that such changes would create in terms of work, marriage, and unwed childbearing.

A few years after Losing Ground, Murray became interested in the topic of IQ. It related to themes he’d already been writing about, he found, and most social scientists had neglected the literature on the subject. He decided to write a book about it but worried that the Harvard psychology professor Richard J. Herrnstein—who had written IQ in the Meritocracy in the early 1970s and an article in The Atlantic about fertility differentials by IQ in 1989—might be thinking the same thing.

Murray called to ask. Herrnstein had no such plans, but he suggested that the two write a book together. Murray agreed. For this project, he moved to the American Enterprise Institute. The Bell Curve, appearing shortly after Herrnstein’s death in 1994, is several books in one. It summarizes the academic literature about intelligence and its measurement. It presents an original study based on the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79), testing the theory that intelligence is a powerful predictor of life outcomes. And in its later chapters, it dives headfirst into the forbidden topics that it’s best known for, including racial differences in IQ.

A sort of cognitive horsepower, IQ is the ability to process complicated information, and it can be measured as accurately as any psychological trait. High IQ is almost a prerequisite for success in many high-paying occupations, and it’s measurably beneficial to workers in many lower-skilled jobs, too.

As Herrnstein and Murray explained, a “cognitive elite” was emerging based largely on this characteristic. College attendance had grown, and universities had increasingly relied on standardized tests that correlate strongly with IQ, so the brightest kids from around the country could demonstrate their smarts and head to the top schools. Such tests had brought Murray from Iowa to Harvard.

That’s often called “meritocracy,” but as Herrn- stein and Murray explained, people don’t do anything to earn their IQs. Quite the contrary: IQ is significantly genetic in origin; and in 1994, there was little evidence that deliberate environmental interventions—short of, say, adopting a child into a new family—could raise or lower someone’s IQ. (More recent studies suggest that mandatory-schooling laws did have that effect, to the tune of one to five added IQ points per year.) In other words, society was stratifying based on a trait that is partly inherent and, at any rate, very hard to change.

Like the statistics in Losing Ground, Herrnstein and Murray’s analysis of the NLSY79 stands out today for its simplicity. Even at the time, researchers were building increasingly sophisticated statistical models to explore their data sets, but Herrnstein and Murray avoided that “bottomless pit” to tell a story.

The NLSY79 had given its subjects the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), which Herrnstein and Murray believed measured IQ well, in their teens and early twenties, and then followed these kids to see how they did. Herrnstein and Murray used the data to answer this question: If all you know about someone is his IQ and a number summarizing his parents’ socioeconomic status, or SES (combining income, education, and occupation), which will better predict his outcome? To eliminate the role of race, these analyses were run only on whites.

On metric after metric—poverty, unemployment, out-of-wedlock childbearing, dropping out of high school, getting a college degree, crime—IQ proved the better predictor. One might object that neither IQ nor SES was a fixed determinant of someone’s future (Herrnstein and Murray noted this themselves) or that the approach is unsophisticated. But these analyses issued a challenge to social science’s focus on SES.

Then the book turned to race. It’s undisputed that black Americans score lower on IQ tests than whites, on average. Herrnstein and Murray emphasized that a difference in averages says nothing about individuals: millions of blacks are smarter than millions of whites. They also summarized the debate over whether this gap was a function of whites’ and blacks’ differing social environments or instead reflected some genetic difference.

After laying out the evidence in detail both ways—for example, statistically controlling for SES reduced the black/white IQ gap by only about a third, but the gap had been shrinking in recent years, and children fathered by white and black U.S. servicemen in Germany following World War II had similar IQs—they presented their ultimate verdict: “It seems highly likely to us that both genes and environment have something to do with racial differences. What might the mix be? We are resolutely agnostic on that issue; as far as we can determine, the evidence does not yet justify an estimate.”

Murray told me that Herrnstein and he had applied “ordinary rules of evidence and Occam’s razor.” Many readers, though, winced at the idea of treating a genetic IQ gap among racial groups the way one would treat any other topic.

The Bell Curve then asked whether society was getting less intelligent on the genetic level because lower-IQ women were having more children than smarter women. (On the environmental level, society was actually getting smarter: in a phenomenon that Herrnstein and Murray christened “the Flynn Effect,” IQ scores had been rising for generations, far too quickly to be the result of genetic changes.)

Finally, the book also reiterated Murray’s call to end welfare, arguing that redistribution was dysgenic:

We can imagine no recommendation for using the government to manipulate fertility that does not have dangers. But this highlights the problem: The United States already has policies that inadvertently social-engineer who has babies, and it is encouraging the wrong women. . . . We urge generally that these policies, represented by the extensive network of cash and services for low-income women who have babies, be ended. The government should stop subsidizing births to anyone, rich or poor.

The Bell Curve inspired even greater pushback than Losing Ground had. Articles and entire books appeared in response, raising every conceivable objection: the AFQT isn’t an IQ test; IQ tests are racially biased; many forms of intelligence exist; other ways of measuring the environment make it more competitive with IQ as a predictor of outcomes; race is a social construct; racial groups’ IQ scores respond to social conditions more than the book acknowledged; Herrnstein and Murray’s sources were racist.

One can spend weeks reading these old debates and taking stands on each sub-issue. (Thomas Sowell’s American Spectator review, “Ethnicity and IQ,” and James Heckman’s Reason review, “Cracked Bell,” are two good critical takes.) My own view is that Herrnstein and Murray had gotten ahead of the evidence on genetics and that they should have kept dysgenics out of welfare policy.

Yet The Bell Curve is convincing when it comes to the power of IQ in modern societies. Much of what it said was indeed just summarizing current science, as numerous experts showed during the controversy. And its themes continue to resonate, sometimes in unexpected ways: witness the rise of “hereditarian leftists,” such as socialist pundit Freddie deBoer and liberal behavior geneticist Kathryn Paige Harden, who accept that genes powerfully influence how individuals fare in modern societies but argue that this is a reason to help the disadvantaged. Advances in genetics have also kept alive the debate over race, though modern geneticists prefer the term “human populations.” A 2018 New York Times article by Harvard’s David Reich urged acceptance of the fact that these populations differ on the genetic level in important ways:

Recent genetic studies have demonstrated differences across populations not just in the genetic determinants of simple traits such as skin color, but also in more complex traits like bodily dimensions and susceptibility to diseases. . . .

I am worried that well-meaning people who deny the possibility of substantial biological differences among human populations are digging themselves into an indefensible position, one that will not survive the onslaught of science. I am also worried that whatever discoveries are made . . . will be cited as “scientific proof” that racist prejudices and agendas have been correct all along, and that those well-meaning people will not understand the science well enough to push back against these claims.

That’s not an endorsement of The Bell Curve, but it’s an expansion of the range of acceptable opinion.

Murray returned to the topic of race in 2020’s lengthy Human Diversity—which didn’t reiterate his position that the black/white IQ gap is partly genetic but did summarize the emerging science of genetic differences across human populations, in addition to exploring the literature on sex differences. For this reason, I found Human Diversity more cautious than The Bell Curve, but Murray disagreed. Given the broader scope of the newer book, including differences in personality and social behavior, he didn’t think that there was a good reason to focus on IQ specifically: “The only reason to have emphasized IQ is to say, ‘And oh, by the way, on something I took so much shit about, we were right on that, too.’ ”

Murray’s latest book, the shorter Facing Reality, steers clear of discussing the causes of racial gaps. But, inspired by the mess of a public debate that followed the George Floyd protests of 2020, it tries to force America to confront the fact that racial gaps in crime and cognitive ability exist. It explains, for example, that the race gap on academic tests stopped narrowing in the 1990s and that blacks commit crimes at higher rates than whites by every available measure.

“Often, Murray notes, public debates start with an assumption that any racial disparity must result from discrimination.”

Yet where his earlier books drew critics’ ire for years after their publication, Human Diversity and Facing Reality hardly registered on the national radar. Why can’t Charles Murray annoy people like he used to? “I went into Facing Reality saying, ‘It is your obligation to write this book because you’re one of the few people who is in a position to do it without putting their career in jeopardy’—and nothing happened,” he said. He’d even declined to dedicate the book to anyone and kept his usual agent out of the process in order to protect her from blowback. “It’s almost as if, in the current intellectual climate, it is no longer necessary to argue with people who say things like I’ve been saying,” he observed. “Given my history and my age and everything else, apparently I’m ignorable. You don’t have to confront the data.”

On such matters, the truth is one question, and whether we should talk about it is another. Numerous thinkers have urged commentators to avoid such discussions for various reasons: it’s demoralizing to see one’s race characterized as inherently less smart on average; the science is too shaky to permit strong conclusions; people will be tempted to jump from a difference in group averages to a belief that all whites are smarter than all blacks; historically, a belief in genetic IQ differences has led to monstrous policies. In a recent discussion with Murray, writer Coleman Hughes urged viewers to think about the situation that black parents would find themselves in if it became normal to talk about the IQ gap on the nightly news.

Murray believes that compelling reasons exist to talk about racial differences, that efforts to sideline the genetic question have failed, and that any practical consequences of opening up the discussion can’t be worse than the status quo. For many purposes, he notes, public policy and public debates start with an assumption that any racial disparity must result from discrimination. If we cannot talk about racial gaps in IQ and crime, we cannot explain why this assumption is false, and therefore we cannot stop the stampede toward race-based policies designed to equalize outcomes.

When I noted his discussion with Hughes and asked if he worried about the consequences of a franker debate, especially adding genetics to the mix, Murray responded:

We’ve had a natural experiment; we’ve tried for 60 years to not talk about all those wounding things in public. And what has come out of it is the worst racial polarization since the Civil Rights Act—it’s been building over a long period of time. We have colleges dropping the SAT. We have Oregon outlawing minimum standards in math and reading and writing and so forth. We have a rhetoric in which whites are called evil and oppressive, and not just privileged but, worse than privileged, racist, no matter how hard they try not to be racist, and in which “colorblind” is hate speech, “melting pot” is hate speech. . . . I could keep on going. . . . So when you tell me that I am going to create bad stuff by now saying, “Look, we’ve probably got differences that are genetic to some degree,” I don’t buy it. I don’t see how it could be any worse.

Does Murray enjoy stirring up controversy? He doesn’t write with the freewheeling joy or spiteful rhetoric of someone who revels in political incorrectness. He has a clear prose style and presents well-crafted arguments that aim to convince an open-minded skeptic. Yet he’s no stranger to provocation.

This tension lays at the heart of a 1994 profile of Murray by Jason DeParle in the New York Times Magazine, titled “Daring Research or ‘Social Science Pornography’?” Written in the lead-up to The Bell Curve’s release, the profile followed Murray on a trip to Aspen, Colorado, during which “the man who would abolish welfare” flew first-class, drank fancy wines, and unguardedly doled out quotable quotes to the reporter, from using the term “white trash” to admitting that the topics of The Bell Curve offered “the allure of the forbidden.” “Social-science pornography,” from the article’s title, wasn’t an allegation from a Murray hater; it was an off-the-cuff comment from Murray himself, describing how his data could answer such questions as which types of white kids are most likely to drop out of high school. “Murray’s persona in print is that of the burdened researcher coming to his disturbing conclusions with the utmost regret,” DeParle wrote, “but at the moment, he seems to be having the time of his life.”

DeParle also mentioned an incident from Murray’s past:

In the fall of 1960, during their senior year, [Murray and his friends] nailed some scrap wood into a cross, adorned it with fireworks and set it ablaze on a hill beside the police station, with marshmallows scattered as a calling card.

[An old friend of Murray’s] recalls his astonishment the next day when the talk turned to racial persecution in a town with two black families. “There wouldn’t have been a racist thought in our simple-minded minds,” he says. “That’s how unaware we were.”

A long pause follows when Murray is reminded of the event. “Incredibly, incredibly dumb,” he says. “But it never crossed our minds that this had any larger significance. And I look back on that and say, ‘How on earth could we be so oblivious?’ I guess it says something about that day and age that it didn’t cross our minds.”

To some of Murray’s detractors, this was a chance to paint him as a white-hooded cross-burner. Since even the Times didn’t portray the incident that way, however, others have drawn a different connection between this story and his later work, one in which the through-line is a certain racial obliviousness. DeParle, for example, wrote that a controversial passage from The Bell Curve recalled “the high-school prankster who burned a cross, only to learn later what the fuss was all about.”

I talked with Murray about the DeParle profile (he admits being casual in his language to convey a certain persona), the cross incident (“the kind of thing that’s so stupid that only teenagers could do it”), and whether he enjoys controversy. He did confess to a contrarian streak: “Any time something is the conventional wisdom, there is an itch within me to say, ‘Oh, yeah?’ ”

But if there’s part of him that enjoys the fire he’s come under over the years, he said, “it must be hidden really deeply.” He was depressed after The Bell Curve came out, especially because people accused him—falsely—of having the numbers wrong. “There was no part of me that I could tap into that was saying, ‘Isn’t this cool?’ ”

Nearly 20 years after The Bell Curve, Murray published Coming Apart, the third book of his to make a major impact. It tied into The Bell Curve’s theme of a society increasingly stratified along class lines but viewed the topic through a less IQ-focused and more sociological lens. Murray told the story of how the social problems once associated with the “underclass,” including unwed childbearing and lack of work, had afflicted lower-educated whites more generally, while elite whites had self-segregated. Some accused Murray of neglecting the role of economics in these patterns. But Murray saw something happening within white America that few others noticed, and that no one can deny a decade later, given lower-educated whites’ role in both Donald Trump’s election and the opioid epidemic.

Coming Apart serves as a sturdy bridge between Murray’s most high-profile works and the impressive assortment of other books he has written. Some of these, like In Our Hands and Human Diversity, update Murray’s analyses in his most well-known areas of expertise; others flesh out the lessons that his work holds in a specific issue area, as in Real Education, which (among other proposals) urges educators to grapple more effectively with the fact that students have a wide range of cognitive ability.

But still others—such as In Pursuit, What It Means to Be a Libertarian, American Exceptionalism, and By the People—deal with deeper matters. These books are key to understanding what animates Murray, as they explain his thought in a less fraught context.

Murray believes that humans want to gain the satisfaction that comes from a life well lived. People want to earn their own way, make use of their talents, overcome challenges, and feel valued. They want to believe that, without their hard work, their families and communities would be worse off. Left to their own devices, with a limited government that keeps the peace, individuals and communities can strive toward that ideal. Murray especially has a soft spot for small towns, as shown by his choosing to live in a community of fewer than 200 people. But when a large, impersonal government provides too much, it robs citizens of the satisfaction, dignity, and self-respect that comes from taking care of themselves and one another.

Murray also has a deep love of the American Founding. Having once called himself a libertarian, he now goes by “Madisonian.” He believes that the Founders got a lot right when it came to enabling citizens to pursue happiness and that early Americans really were an exceptional people, including in their insistence on limited government and in their dedication to an individualistic creed where people were judged on their merits, not on their social class at birth.

Murray does not deny the horrors of America’s racial history. But alongside the positive developments on race and freedom since the Founding, he thinks that America has lost parts of what made it special. In By the People, Murray pinpointed 1937–42 as the period when the Constitution’s limits on the federal government dissolved in a series of Supreme Court decisions. Facing Reality raises the alarm about the threat that left-wing racial ideology poses to America’s individualistic streak.

“Murray has a deep love of the American Founding. Having once called himself a libertarian, he now goes by ‘Madisonian.’”

Over the years, Murray has offered ideas for restoring what America has lost. In Pursuit sought a return to the ideals of Jeffersonian democracy, with more local control; By the People proposed lawsuits and civil disobedience to tame the federal administrative state. Now, he’s mostly pessimistic. “Even if we were to try to bring things back,” he laments, there’s so much constitutional, legal, and institutional “sludge” to wade through.

For now, Murray doesn’t have another book in the works. He’s spending some time working on databases, something he loves doing. One of his projects is to post publicly more of the data behind Human Accomplishment, a 2003 book in which Murray ranked history’s most impressive artists and scientists based on the attention they had received in encyclopedias and histories from around the world.

How is Murray faring on that all-important question of a life well lived? He recalled the advice he gave in The Curmudgeon’s Guide to Getting Ahead, a short, lighthearted book from 2014: “Marry your soul mate and find a vocation you love, and everything else is a rounding error. I’ve done both of those things.”

As for his family, he feels indebted to his wife, Catherine Bly Cox, for the disproportionate role she played in raising the children while he focused on his work. The two, both from Newton, began seeing each other about a year after Murray’s divorce.

“I’ve been a good dad in reasonable ways,” Murray said. “Have I been as good as other dads are? No, I’ve spent too much time in this room, sitting in this chair, to have been as good as other dads can be.” In Pursuit argues that the satisfaction that one gains from an endeavor is proportional to the effort put in, which Murray has become only more aware of since he wrote it: “I don’t think the kids paid too heavy a price because they have such a wonderful mother, but the satisfaction I’ve taken from raising kids is not as much as it would have been if I had made a greater investment, and that’s just a reality of human life. There are trade-offs.”

As for his professional accomplishments, most writers would envy Murray’s influence. But Murray says that only one of his books will last 100 years, or maybe even 1,000—Apollo, which he coauthored with Cox in the 1980s. Rather than focusing on the astronauts who went to the moon, Apollo tells the story of the people who designed the spacecraft, planned the missions, and guided the ships, based on extensive interviews.

“What will people remember about the twentieth century 1,000 years from now?” he asks. “Catherine argues that they’ll remember two things. They will remember World War II, which she thinks will take on kind of a Homeric ‘good versus evil’ that will keep it alive in the same way that a few wars have been kept alive. She says the other thing will be—and I agree with this—it’ll be the century in which human beings first left the earth. And the first time they did it was Apollo, and we will be a kind of primary source for historians, for as long as people write about it. I’m not saying that it will be a bestseller 1,000 years from now. But that book will last.”

Top Photo: Charles Murray in his office in 1994, the year he published The Bell Curve, coauthored with Richard Herrnstein (DENNIS BRACK/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)