In the late 1940s, Nobel Prize–winning French author Albert Camus saw it all coming: pestilence, quarantine, untreatable illness, a cratering economy, citizens cowering in their homes, and “frontline workers” willing to sacrifice themselves for their neighbors. No, he didn’t predict that a novel coronavirus would leap from bats to humans in the closing days of 2019, but he knew as well as any epidemiologist that terrible diseases periodically explode through human populations, and in his novel The Plague (translated from the French La Peste), he warned his contemporaries about it: “Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world, yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.”

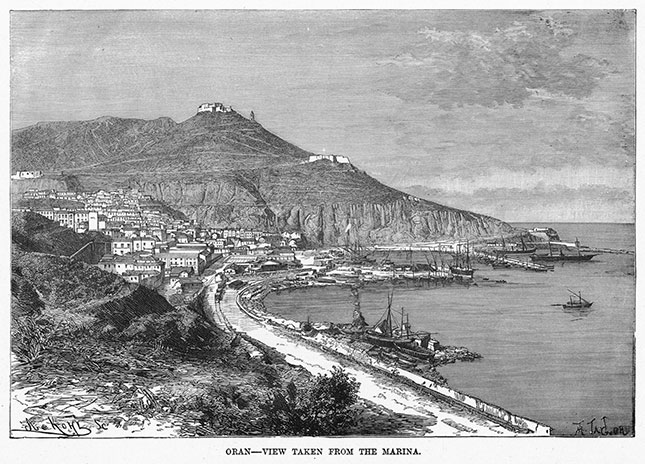

Arguably the best work of fiction about a disease nemesis ever written, The Plague describes a fictional outbreak of bubonic plague in the French Algerian city of Oran shortly after World War II. It is a story of a pestilence in a modern European city on the African continent with telephones, cars, and other postwar technologies. Colonial France conquered Algeria in 1830 and ruled it until 1962. Camus was born there to French pieds-noir (“black feet”) parents—citizens who lived in Algeria before independence—in the small coastal town of Dréan (then Mondovi), near the Tunisian border. He studied philosophy at the University of Algiers and joined the French Resistance when the Nazis invaded France in 1940, working primarily as editor-in-chief of the outlawed newspaper Combat. He was an existentialist philosopher as well as an author of fiction, and his novel The Stranger enjoyed a decades-long run as required reading for university students.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Some assume that Camus’s plague novel is an allegory of the Nazi occupation. It isn’t, really, though he surely drew from his experience in the Resistance when he wrote it. No, The Plague is precisely what it’s purported to be: the story of a city during a horrific outbreak, as told through the perspective of its narrator, Dr. Bernard Rieux. It’s also a morality tale and a warning to all that the human race is bound to experience something like it again. The Plague sears itself into the mind; hardly anyone who reads it ever forgets it.

A million and a half people live in Oran today, with 3.5 million in the metro area. In Camus’s time, the population was about 200,000, a mixture of French, Jews, Arabs, and Berbers. The city is more than just a setting. Its citizenry, far more than even the narrator, is the novel’s main character. The city itself is hot, dry, and treeless, its residents obsessed with making money and hanging out in cafés. It is entirely ordinary, cramped and provincial, a city on the Mediterranean that oddly turns its back on the sea.

After a brief prologue, the action begins when, early one morning, as he leaves his surgery, Rieux steps on a dead rat on the building’s landing. Rats are soon everywhere—in hallways, on sidewalks and streets, and in gutters. Rieux finds a dozen in one garbage can. Most of the rats are dead, but some are in their final death throes, hacking up tiny droplets of blood.

At first, the townsfolk find the rats a disgusting nuisance, forgetting that the feeling of disgust is a human survival instinct, protecting us from contagion by repelling us. The people of Oran seem to have forgotten that rats are vectors for some of the worst diseases—including the worst of all—ever to afflict humanity.

Geysers of rats then erupt from sewers and drains and die everywhere, in apocalyptic numbers. Even citizens who know next to nothing of bubonic plague or its transmission (the pathogenic Yersinia pestis bacteria travels from rats to humans via fleas) know that something is wrong now. An ancient part of their biological memory has been activated: “This strange phenomenon, whose scope could not be measured and whose origins escaped detection, had something vaguely menacing about it,” the narrator says.

Soon a man named Michel dies of a mysterious illness. His death goes unnoticed at first, as new outbreaks always do. But it doesn’t take long before people understand that something worse than a mere plague of rats is upon them.

Rieux goes through the same psychological process as everyone else in the story—the same process that many experienced when the coronavirus pandemic descended on us—beginning with obliviousness before being nudged to a faint awareness. A period of denial follows, which leads to dread, then to horror, and finally to resignation. The early middle of the journey is the hardest, mostly because it’s as surreal as it is dangerous:

Our townsfolk were like everybody else, wrapped up in themselves; in other words they were humanists: they disbelieved in pestilences. A pestilence isn’t a thing made to man’s measure; therefore we tell ourselves that pestilence is a mere bogy of the mind, a bad dream that will pass away. But it doesn’t always pass away and, from one bad dream to another, it is men who pass away, and the humanists first of all, because they haven’t taken their precautions. . . .

Our townsfolk were not more to blame than others; they forgot to be modest, that was all, and thought that everything still was possible for them; which presupposed that pestilences were impossible.

Rieux is a doctor. He knows the plague when he sees it, though he has never seen it before. Yet he tries to reason it away at first. Plague is a fourteenth-century malady, isn’t it? Or at least a nineteenth-century one. What’s it doing here, in modern times? He tells himself that plague has vanished from temperate climates, that Western Europe hasn’t known any cases for a long time (though Oran is on the African continent, not in Europe). Then he remembers that Paris had an outbreak 20 years earlier.

Initially, Oran’s medical establishment responds in a way that foreshadows the Chinese Communist Party’s early response to Covid-19 in Wuhan. They know that they have an outbreak on their hands, but they decide to keep it a secret. Even Rieux himself, an otherwise exemplary person, is tempted to go along with the lie, partly because he’s still half-lying to himself. He knows the truth, but he flinches when the question is finally raised about whether to sound a public alarm. He tells his colleagues that he is willing to say that the disease isn’t the plague. It would put minds (falsely) at ease. He also fears a heavy-handed government reaction, if and when the word gets out.

So doctors say that it’s not plague, while city officials acknowledge that there is an outbreak of some kind—but they downplay it, responding with half-measures: “The measures enjoined were far from Draconian and one had the feeling that many concessions had been made to a desire not to alarm the public. The instructions began with a bald statement that a few cases of a malignant fever had been reported in Oran; it was not possible as yet to say if this fever was contagious.” Yet the threat is real and growing. It’s the plague, a disease that reduced populations by roughly half more than once, from the Plague of Justinian to the Black Death.

Perhaps initial denials that a plague is coming or has arrived is what we should always expect from governments. It happened a mere 30 years before Camus penned his tale. During the great “Spanish flu” pandemic in 1918, most Western governments, including America’s, never publicly mentioned the disease.

Oran’s municipal government eventually takes the contagion seriously. Virulent outbreaks that scythe through communities eventually can’t be denied, any more than gravity can be denied. So Oran’s exterminators finish off the rat population by blowing poison gas into the sewers. Utility workers monitor the water supply. Citizens are advised to maintain strict hygiene, and those bitten by fleas are to monitor themselves and alert the authorities. None of this is enough to stave off a tsunami of cases, so the ultimate authorities, in Paris, issue orders to Oran via telegram: “Proclaim a state of plague and close down the town.”

The Plague’s characters find themselves trapped by their outbreak. With no warning, security forces surround the town and forbid anyone from leaving. In an era before smartphones and the Internet, Oran’s citizens have no way of reaching friends and family outside the city, and the circuits are too busy for most old-fashioned phone calls to get through. No one is even allowed to mail letters, lest a micron of bacterium be spread via paper or stamp. Even going outside is dangerous (since that’s where the fleas are), leading to a state of suspended animation familiar to us today: “exile in one’s own home.”

It’s a strange sort of exile, though, for the citizens of Oran, as for us today. Even during a pandemic, none of our five senses detects direct danger. Our primitive threat-detection system—the evolutionarily ancient “lizard brain” that makes us afraid of the dark as children and sometimes as adults, that makes us jump at loud noises, that may warn us that something is amiss—is defenseless against invisible microbes.

Oran’s quarantine at gunpoint is harsher than our lockdowns, and crueler. Our stay-at-home orders were put into place to protect us; Oran’s quarantine protects the rest of the world from Oran. It does no good for the unlucky souls ensnared in it. By preventing people from fleeing, it condemns staggering numbers of them to death. That doesn’t make the quarantine any less necessary, but it does make it much harder to bear.

Even the waters and beaches of the Mediterranean are off-limits to those without permission to go there, the unstated but presumed reason being that the sea is a plausible means to break quarantine and spread the infection. Loneliness and nostalgia, and the desire to live in any time but the present, become the dominant emotions: “The feeling of exile—that sensation of a void within which never left us, that irrational longing to hark back to the past or else to speed up the march of time . . . those keen shafts of memory that stung like fire.”

Oran’s local economy doesn’t shut down in quite the same way that the global economy shut down during the coronavirus pandemic—restaurants and cafés remain open, for instance—but the city’s links with the rest of the world, economic and otherwise, are severed, so there’s less work to be done than before. Commerce, too, the narrator says, “died of plague.”

Most of Oran’s citizens experience aimless days, much as prisoners do. Modern commentators have described the coronavirus pandemic as feeling a bit like Groundhog Day, the Bill Murray comedy where his character must relive the same day over and over again. Camus imagined the experience more starkly: “The whole town lived as if it had no future.”

Relentlessly bleak as it is, The Plague is oddly comforting to read during this crisis. It reminds us that past generations have experienced similar hardship and that things could be worse. We are not dealing with bubonic plague, a disease inspiring such dread that Rieux has a hard time even saying the words out loud.

In the modern world, we can treat bubonic plague with antibiotics and save up to 90 percent of patients (which still makes it far more lethal than Covid-19), but before we learned how to treat it, Yersinia pestis killed between 30 percent and 90 percent of its victims. (The pneumonic form of the disease, where the lungs, rather than the lymphatic system, are infected, is almost invariably fatal if untreated. It can also be spread by respiratory droplets, without fleas as an intermediate vector.)

Remarkably, though Camus never properly experienced a plague or a pandemic himself—he was only five when the novel H1N1 influenza virus burned its way across the globe in 1918—he captures what it feels like precisely. Perhaps those who awarded him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957 noticed this, too. Camus pulls this off by drawing from his imagination and his memory of other traumas. He worked for the French Resistance against the Nazis, after all, and he wrote this book almost immediately after the war ended.

That experience matters. Pestilences and wars provoke similar emotions in people. I can attest to this myself after experiencing both, first as a war correspondent in the Middle East and Russian-occupied Georgia and second as a person living during the coronavirus pandemic, like everyone else. We can’t take a plague personally, though. The enemy doesn’t think, doesn’t hate. It doesn’t even meet all the definitions of a life form—least of all, a wrathful, sentient one.

Rieux can’t treat the plague any better than doctors can treat Covid-19. He has no plague serum on hand. He has to wait a long while for a shipment from Paris to arrive, and when it finally does, the stuff scarcely works. The characters are almost entirely helpless. Normally, that’s considered a bad move for novelists, who need to let at least one of their characters engage in a heroic battle with an enemy. But The Plague is no beach read. It’s about how human beings endure long periods of suffering that they are powerless to stop. No one knows how long the epidemic will last, as it takes “its daily toll of deaths with the punctual zeal of a good civil servant.”

Oran’s journalists have a hard time covering the story in local newspapers after a while. The bodies keep piling up at a steady rate. There is nothing much new to say, with no progress being made. There are no great battles, no scandals, and no shocking new revelations to cover. Nor is herd immunity something to look forward to in a worst-case scenario—not when the disease kills the majority of people who catch it. It’s just a grim slog. “The truth,” as Camus writes, “is that nothing is less sensational than pestilence, and by reason of their very duration great misfortunes are monotonous. In the memories of those who lived through them, the grim days of plague do not stand out like vivid flames, ravenous and inextinguishable, beaconing a troubled sky, but rather like the slow, deliberate progress of some monstrous thing crushing out all upon its path.”

The worst of the emotional pain is eventually blunted as an exhausted resignation sets in. The townspeople have “adapted themselves to the very condition of the plague, all the more potent for its mediocrity,” none “capable any longer of an exalted emotion; all had trite, monotonous feelings. . . . The furious revolt of the first weeks had given place to a vast despondency.”

At the epidemic’s peak, the death toll is well over 100 daily in a city of roughly 200,000 people, the vast majority strangers to one another. As a percentage of the population, the daily toll isn’t so large—amounting to about one in 2,000. And while eventually everybody knows someone who dies, nearly all the 100 per day are faceless numbers. It’s scarcely possible for human beings to process staggering numbers of deaths that involve strangers, which is why broadcast journalists today feature stories of the fallen and their surviving loved ones. Camus could have made that point by writing character sketches of those who die in The Plague, but instead he uses a somber thought experiment to capture the enormity of it all.

The doctor remembered the plague at Constantinople that, according to Procopius, caused ten thousand deaths in a single day. Ten thousand dead made about five times the audience in a biggish cinema. Yes, that was how it should be done. You should collect the people at the exits of five picture-houses, you should lead them to a city square and make them die in heaps if you wanted to get a clear notion of what it means. Then at least you could add some familiar faces to the anonymous mass.

In Camus’s telling, Yersinia pestis doesn’t represent fascism or war or any other particular calamity. It’s a stand-in for calamity in general. Camus uses Tarrou, a character who organizes a civil-society organization called the Sanitary Squads, as his vehicle for that message. “Rieux, I can say I know the world inside out, as you may see—that each of us has the plague within him; no one, no one on earth is free from it. . . . All I maintain is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences.”

In Camus’s fictional world, there is no shortage of people who join forces against the pestilences—not just Tarrou and his volunteers but also those conducting funerals and burials, despite severe risk of infection from the dead. These characters are like our own frontline workers—doctors, nurses, EMTs, police officers, and so on—who brave the pandemic daily, even without the requisite protective gear, to protect their neighbors, most of them strangers: “Many of the gravediggers, stretcher-bearers, and the like, public servants to begin with, and later volunteers, died of plague. However stringent the precautions, sooner or later contagion did its work. Still, when all is said and done, the really amazing thing is that, so long as the epidemic lasted, there was never any lack of men for these duties.”

The Plague is almost unrelentingly dreary, but even during major crises, we can find at least fleeting moments of pleasure—though it’s easier for those who can seclude themselves from danger by either working at home or living for a time off investments or other income. It’s also easier for those with the psychological ability (which one can acquire through meditation or cognitive behavioral training) to live in the present moment, without pining for the past or dreading the future. We must do our best to live, even during a plague or a war or an economic depression or any other kind of disaster. In one memorable scene, Rieux and Tarrou swim in the Mediterranean (as members of the community in good standing, they are allowed to do so), taking a short vacation, of sorts, from the catastrophe devouring their city.

This is the penultimate scene before the plague’s tipping point. Not long after, the rats return to Oran, but this time they’re not coughing blood. It’s the first omen of good things to come in the entire book. Sure enough, the number of daily victims begins to decline as mysteriously as their number once rose.

The novel doesn’t offer the standard plot trajectory for fiction. The hero is supposed to save the day through cunning and skill. The antagonist—in this case, the plague—isn’t supposed to sulk off in defeat, for no obvious reason. But that is how plagues and pandemics always ended in the real world, at least before we had antibiotics or vaccines. So Camus isn’t exactly cheating here, at least not according to history’s rules, by using a deus ex machina to trigger a climax.

Once the body count begins falling, the entire emotional makeup of Oran is transformed. “It could be said,” Camus writes, “that once the faintest stirring of hope became possible, the dominion of the plague was ended.” The same is likely to happen to us at some point, even before the true end finally comes, with, perhaps, an effective treatment or vaccine. In Oran, the transition is a strange one, as our own likely will be. For even as the plague loosens its grip, people still die. It’s not over just because it’s on the downswing. What is over, however, is the feeling of hopeless, interminable purgatory.

Happiness returns, but with a tragic twist for one of the main characters. Rieux’s friend Tarrou, who founded and led the Sanitary Squads, is the last person in Oran to perish from Yersinia pestis. He expires while everyone else is out celebrating.

Some say that Camus may have been inspired to write The Plague by a real cholera epidemic that broke out in Oran in 1849, 100 years before the novel takes place. Others wonder if it’s based on Oran’s experience with the bubonic plague in the 1500s and 1600s. But the narrative doesn’t have to draw on any real event. The Plague is simply a fictional tale of a premodern horror unleashed upon the modern world. It is also, like Daniel Defoe’s now-dated Journal of a Plague Year (first published in 1722) and Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 film Contagion, a warning that a horrifically deadly disease like this can return at any time and that modern people are arrogant to think themselves immune.

In late 2019, when the first hints of the coronavirus pandemic hit the front pages of newspapers—and especially when the Chinese government locked down 11 million people in Wuhan—Camus’s final words should have sent a chill down the spine of any reader wise enough not to dismiss them.

As he listened to the cries of joy rising from the town, Rieux remembered that such joy is always imperiled. He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.

Top Photo: Albert Camus, 1913–60 (INTERFOTO/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)