On Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard back-to-back oral arguments in Little v. Hecox and West Virginia v. B.P.J., cases involving state laws that restrict girls’ and women’s sports to biological females.

The fascinating—and lengthy—arguments didn’t change much. The challenges to the Idaho and West Virginia laws will fail under basic principles of fairness. Judges don’t simply apply their own sense of fairness, of course, but there is both constitutional and statutory basis for that consideration here. States have enacted biological-sex-based restrictions for the same reason we have female categories of sports in the first place: men and women are biologically different in ways relevant to athletic competition, so it makes sense to separate the sexes.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause doesn’t block common-sense distinctions that reflect inherent male advantage in sports. Nor can Title IX, which was enacted to give girls and women the same educational opportunities as boys and men, be read to require inclusion of biological males in female sports categories (and may well require their exclusion).

All the rest is cultural commentary. People’s “gender identity” is irrelevant to biologically based distinctions in sports. There’s no improper discrimination here, based on animus, irrationality, or anything else.

That is, in substance, what the states’ lawyers argued. Idaho’s solicitor general put the core point bluntly: “sex is what matters in sports.” West Virginia’s solicitor general argued that separating teams by sex is how schools ensure that girls can “safely and fairly compete.”

Those statements aren’t provocative; they’re descriptive. Female sports categories exist because the sexes differ in ways that matter for athletic performance and safety, especially (but not only) after puberty. Nothing is unseemly about the law’s drawing lines that track real biological differences pertinent to a particular activity.

The doctrinal vocabulary matters here. The challengers— a college student and a high schooler, both biological males who identify as female—want the Court to treat these laws as a kind of suspect “transgender classification,” while simultaneously relying on the continued existence of girls’ and women’s teams. But if the female category remains, the Court has to be able to say what it is. And it was striking to watch the challengers’ position run straight into that brick wall.

In the Idaho case, Justice Samuel Alito pressed the basic equal-protection predicate: “What does it mean to be a boy or a girl or a man or a woman?” The attorney arguing for the challengers ultimately conceded: “We do not have a definition for the Court.”

That exchange matters for a reason deeper than courtroom theatrics. Equal-protection analysis doesn’t float free of the categories it is asked to police. If the state is allegedly “discriminating on the basis of sex,” we have to be able to define sex in a way that’s administrable for schools, consistent for courts, and tethered to why sex-separated sports exist in the first place. Otherwise, the female category becomes a mere label that’s rhetorically retained but functionally dissolved.

Title IX pushes in the same direction. Its entire purpose was to expand girls’ and women’s opportunities in education—including athletics—precisely because opportunities had historically been denied, in favor of boys. West Virginia’s lawyer captured the commonsense premise: “biological sex matters in athletics in ways both obvious and undeniable.”

The challenger’s lawyer in the West Virginia case, of course, took a different view. He insisted that if a particular student lacks “relevant physiological differences . . . there’s no basis to exclude” that student from girls’ teams.

But that argument doesn’t solve the administrability problem. The challenger’s approach would force schools (and inevitably courts) to perform individualized inquiries about hormones, puberty timing, and “relevant physiological differences.” But schools aren’t equipped to run quasi-medical tribunals, and female athletes shouldn’t bear the burden of constant litigation to preserve the integrity of their competition.

More fundamentally, that approach misunderstands the female category. We didn’t create girls’ and women’s sports as a reward for females who can prove a threshold level of athletic disadvantage. We created them as a recognition that sex-linked physical differences are real and pervasive—so that girls as a class can compete, develop, and win in a space not dominated by male physiology.

None of this requires anyone to deny anyone else’s humanity, dignity, or good faith. It doesn’t require a court to settle metaphysical debates about identity. All it requires is something much more modest: to recognize that, in athletics, sex-based categories serve the very equality interest that the Constitution and Title IX were designed to protect.

So yes, yesterday’s arguments were long, lively, and revealing. But they reinforced, rather than undermined, the basic point that states may protect female sports. (Whether they must do so is an issue for another day.) The law has no obligation to pretend that biology is a social construct.

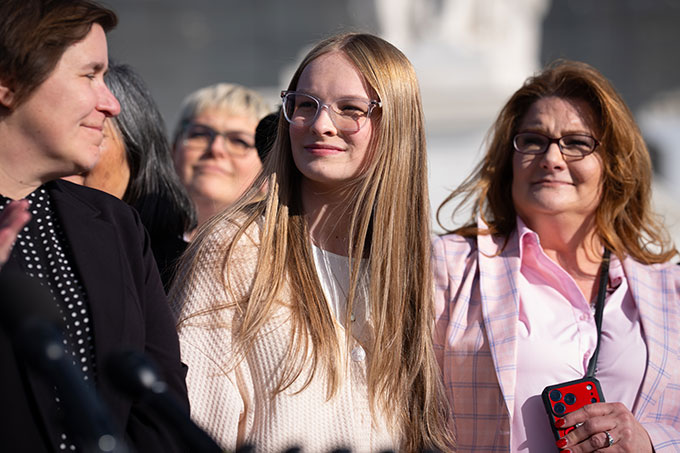

Top Photo by Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post via Getty Images