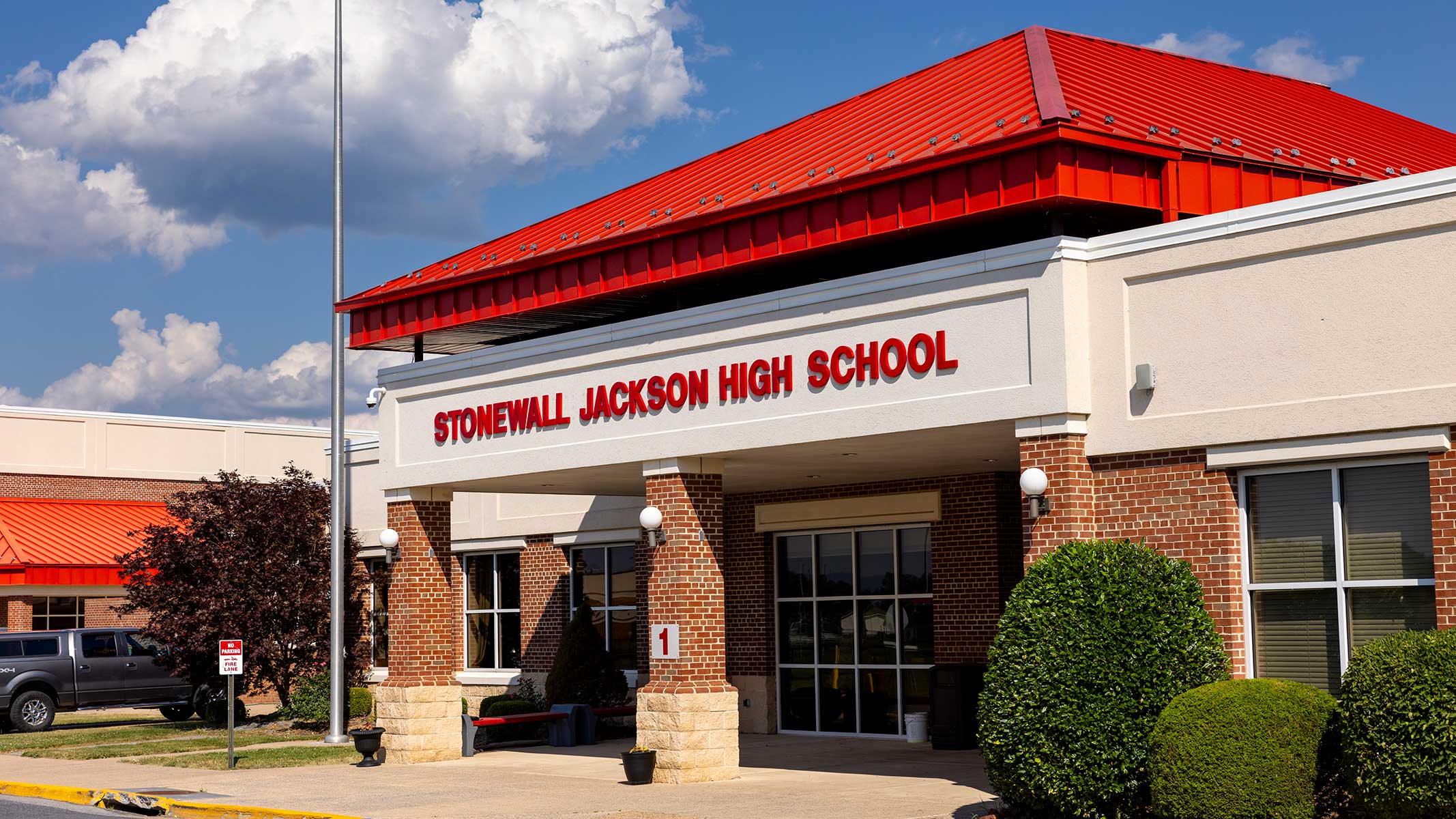

In September, a federal judge ruled that a Virginia school board violated students’ First Amendment rights by reinstating the name “Stonewall Jackson High School.” While Judge Michael F. Urbanski called the case “unique,” his ruling could make the names of many public high schools constitutionally suspect.

Stonewall Jackson High School, located in Quicksburg, a small town in Virginia’s Shenandoah County, opened in 1959 as a whites-only institution and became integrated in 1963. Like many Southern schools of the era, it adopted the name of a Confederate general—likely as a signal of resistance to federal desegregation after the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Whatever its founders’ intentions, the school’s name took on different meanings to students and the local community. Some considered it racist and an affront to blacks. Others argued that Jackson was a “Godly” man, whose name was essential to the community’s identity.

In 2020, the Shenandoah County School Board did an end run around the debate. During the national upheaval after George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, the school board passed a resolution “condemning racism” and committing to an “inclusive school environment for all.” Later that year, despite intense protests, members voted 5–1 to remove Jackson’s name from the school. In January 2021, they settled on the anodyne “Mountain View High School” as a replacement.

Quicksburg residents were incensed, and supporters conceded that the name change was enacted against the community’s wishes. “Sometimes we have to make difficult and unpopular decisions on behalf of all of the students,” Cynthia Walsh, a then–Shenandoah County School Board member who voted for the name change, told the New York Times. “If we are only ever going to listen to the majority, when does the minority ever get represented?”

The majority soon reasserted itself. Starting in 2021, the town elected new school board members who had campaigned on reversing the name change. In May 2024, the board voted, again by a 5–1 margin, to restore the name “Stonewall Jackson High School.”

A month later, two black student-athletes joined the state NAACP chapter in suing the Shenandoah County School Board. Their parents argued that reinstating the name violated their children’s First Amendment rights against compelled speech.

In September 2025, Judge Urbanski of the Western District of Virginia agreed. He ruled that the county’s decision was “exceptionally symbolic” and intended to send a “message favoring ‘Stonewall Jackson.’ ” Students, he reasoned, became “mobile billboards” for the board’s pro-Jackson stance whenever they took part in extracurricular activities and were identified with the school.

This reasoning, however, could apply to almost any public high school. Every school name conveys a “message” of some kind. And every student in extracurricular activities serves as a “mobile billboard” for that message whenever he wears a uniform or is introduced as representing the school.

Consider a counterfactual. Suppose that after its 2020 resolution condemning racism, the Shenandoah County School Board had renamed the school for Martin Luther King Jr. instead of Mountain View. That decision would plainly have been “exceptionally symbolic,” sending a “message favoring” King and rejecting Jackson. Student-athletes wearing jerseys with King’s name would have become “mobile billboards” for the board’s stance. By the court’s logic, students who opposed the pro-King message would have had their constitutional rights violated.

This logic is not limited to this case’s immediate context, in which the county was replacing a Confederate’s name. Every school named after a public figure, regardless of that school’s history, would be subject to the court’s ruling. Thomas Jefferson, for example, is the namesake of more than 450 schools nationwide. At each of those schools, the school board sent a “message” variously endorsing him. In many cases, student-athletes at those schools wear jerseys bearing his name, serving as “mobile billboards” for the school board’s message.

One could reasonably argue that Stonewall Jackson High School should have abandoned its name. A once-segregated Southern school should think carefully about whether and how to deploy the symbols of its past. But the court’s ruling circumvents the democratic process and distorts the Constitution to achieve its desired end.

Photo by Robb Hill for The Washington Post via Getty Images