At San Diego State University (SDSU), ethnic studies students are learning to approach their internships from a “decolonial perspective” and to challenge the “colonizer logic of work.” Thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the university now offers a course called “Ethnic and Gender Studies in the Workplace,” part of a broader project to apply the principles of ethnic studies beyond the campus.

The “Building Decolonized Internship Pipelines” project, which SDSU launched last year, seeks to address a problem endemic to women’s, gender, sexuality, and ethnic studies (area studies) departments: their students are routinely underemployed.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

“Our alumni are slower to receive promotions and many graduates remain underemployed, working part-time positions,” notes the project’s grant proposal, which I acquired via a public records request. These former students’ failures supposedly stem from a “deficit model,” whereby employers see area-studies students “as inherently unwilling or uncapable [sic] of participating in the hegemonic workforce.”

To address this perception—and presumably, to improve students’ chances at gainful employment—the project proposes an unconventional approach: applying decolonial ideology. “To counter deficit models of [area studies] students,” the project aims to create a navigating-the-workplace course and internship program “from a decolonial perspective,” the grant proposal said.

In practice, this means teaching students to be skeptical of the “colonizer logic of work.” That logic, the proposal noted, “seeks to indoctrinate and police students into uncritical, non-self-reflecting citizens who do not interrogate the relationship between capitalism and minoritized cultural practices, values, and traditions.”

One of the SDSU initiative’s key activities is developing an “Ethnic and Gender Studies in the Workplace” course. This course teaches students “how to interrogate capitalism and minoritized cultural practices, values, and traditions” while “challenging and resisting white supremacy, racism and hate, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, imperialism, and contemporary colonialism that are deeply entangle [sic] with professional workplaces.”

The new course is seemingly designed to make area-studies students even less employable. The proposal notes that the course will encourage students “to question specialization,” because “specialized work can create professional identities that center self rather than identities grounded in community and its betterment.” It will also “retain solidarity and allyship,” which is “antithetical to upward mobility and individual recognition prized in many workplaces.”

Employers will likely be wary of a “decolonized” approach. Anticipating that, the proposal outlines how administrators will communicate with “community partners”—the companies that might actually offer students internships.

“[T]hey will know,” the proposal says, that while “profit might be a necessary component of for-profit companies, … a critical consciousness about work and the extraction of labor from students can be complicated and filled with tensions as students navigate trying to imagine a world beyond late capitalism while also operating within its parameters.”

“Ethnic and Gender Studies in the Workplace” is now in the SDSU course catalog, promising in its description to teach “how systemic oppression operates in the professional sphere” and “strategies for advocacy and allyship in the workplace.”

SDSU did not respond to a request for comment.

SDSU’s decolonized internship program is just one in a flurry of new ethnic studies projects in California. In 2024, the Mellon Foundation gave the California State University System $1.5 million to “Expand Ethnic Studies Pathways.” The system used these dollars for nearly a dozen smaller grants to its campuses for projects such as “Advancing Queer and Trans Ethnic Studies” and “Advancing Two Spirit and Indigenous Trans Sovereignty.”

In a recent Wall Street Journal article, I describe the Mellon Foundation’s activist turn. The country’s largest funder of the humanities has embraced a political agenda, single-mindedly focused on advancing “social justice.”

SDSU’s project offers a small but poignant example of the consequences. The Mellon-funded program sets out to teach students that the workplace is oppressive and to prepare them to challenge it. By making students less prepared for post-college life, the Mellon Foundation continues to undermine the case for the humanities.

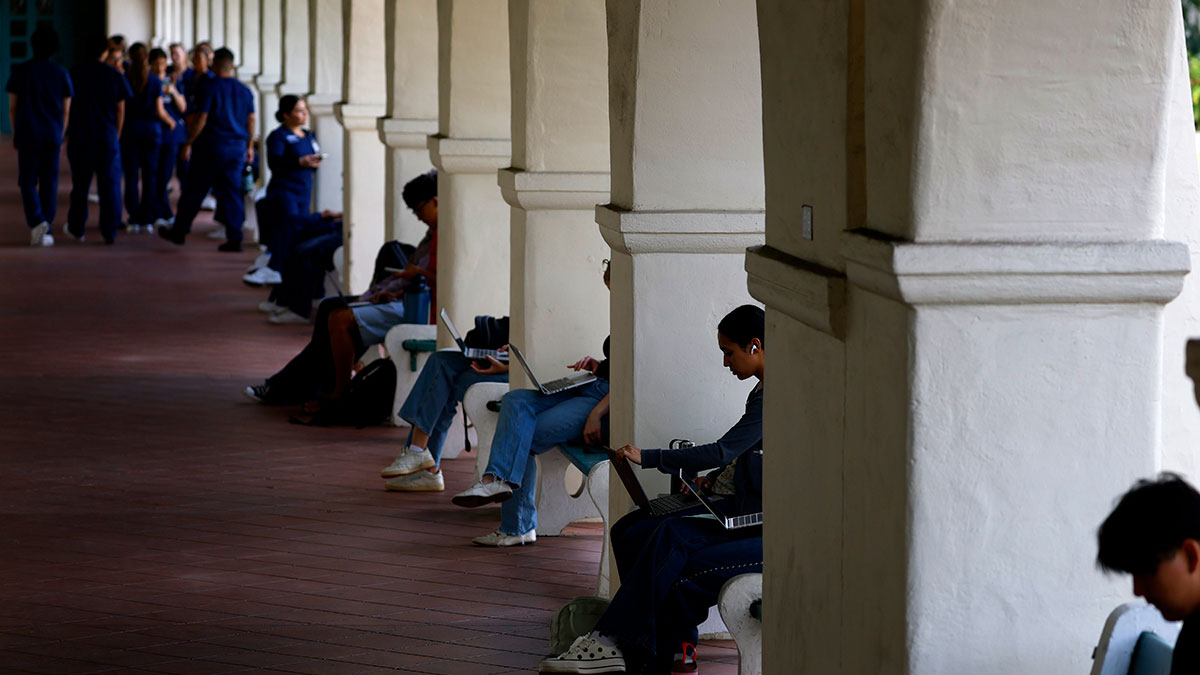

Photo by K.C. Alfred / The San Diego Union-Tribune via Getty Images