Ralph Waldo Emerson was born on May 15, 1803, in the interregnum between two wars: one the revolution that birthed America and the second a bitter sequel that confirmed its independence. The United States then numbered 17. Maine was disputed with British North America; Ohio had joined the Union less than three months before. The sweep of America’s uncertain sovereignty westward ended at the Mississippi. The Louisiana Purchase, negotiated the month before, would not be finalized until later that year, doubling the nascent nation’s size and pushing its border out to the Rockies. To the south, running along the 31st parallel from the Mississippi to the Chattahoochee River, then farther south and east to the Atlantic, was the border with Spanish Florida (encompassing most of modern Florida, southern Alabama and Mississippi, and part of southeastern Louisiana). Only since 1795, under Pinckney’s Treaty, had American ships had the right to navigate the Mississippi freely and ship goods duty-free through Spanish-controlled New Orleans.

Hemmed in by fractious neighbors, menaced by hostile tribes and British agents, the young republic stood poised to break out into a new and wider sense of itself. Both nationally and individually, in both nature and politics, it was this kind of becoming that Emerson celebrated: “Life only avails, not the having lived. Power ceases in the instant of repose; it resides in the moment of transition from a past to a new state; in the shooting of the gulf; in the darting to an aim.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

His early notebooks bear titles like Wide World and Universe. More intellectual than Whitman, less rigid than Thoreau, Emerson emerged as the foremost prophet and celebrant of the boundless possibilities that beckoned both on the expanding American frontier and on the never-settled frontier of the individual soul. He was the right man for the time. America’s existence did not, as the Sartrean formula has it, precede its essence—but before Emerson, that essence was so pragmatic, parochial, and aesthetically underdeveloped as to seem (despite the brainpower of the Founders) like a shallow-rooted tree, its limbs straining backward to catch the receding sun of England, still beholden for its cultural fruits to the artistic modes and mental mannerisms of the empire whose colony it had lately been.

Emerson, Harvard-educated and forward-looking, offered a new vision. The only sin, he told an adolescent America, is limitation. He praised steam power and every surplus of energy, even in its cruder forms. He cherished nature as revelatory of what lies beyond nature, the life of the senses as the royal road to the spiritual. Amid the tumult of democracy, he stood with the minority of the intellect—with, ultimately, that smallest and most essential minority: the free individual. Preacher, lecturer, essayist, sage, Emerson had ultimately “one doctrine,” he said in 1840, “the infinitude of the private man.” He was the American Plato and Marcus Aurelius in one.

Exhortation, moral improvement were the family business. Emerson’s father, a leading Unitarian minister in Boston, died when the future author of Nature was just seven; thereafter, his mother supported the family by running a series of boardinghouses. Despite their straitened circumstances, she was determined that her children should receive a strong education. Emerson attended preparatory school in Boston before matriculating at Harvard at 14—an age not uncommon for freshmen at the time. Already fluent in French, he studied Latin and Greek, history ancient and modern, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, and British empirical philosophy. He worked summers at his uncle’s grammar school and eagerly entered any academic competition offering a cash prize. More than anything, he longed to be a poet. It was a sign of where his true genius lay, however, that while he took second place in a Harvard oratory contest, he was named class poet in his senior year only after six other boys had declined.

Though ambivalent about entering the ministry—and battling an eye ailment possibly linked to tuberculosis—Emerson enrolled at Harvard Divinity School and, in 1829, became pastor of Boston’s Second Church. His congregation loved him; he would later be praised for his “masculine faculty of fecundating other minds.” Yet he soon felt stifled by the role’s prescribed rituals and doctrinal constraints. Serving within those bounds, he believed, meant sacrificing integrity and vitality. “The life which we seek,” he would write, “is expansion: the actual life even of the genius or the saint is obstruction.” Endlessly restated, that core tension—between fate and power, limitation and creative force, obstruction and expansion—and the split in nature or the human spirit it revealed, would preoccupy him for the rest of his life. In 1832, he resigned from the pulpit, commending his parishioners to Providence while affirming his commitment to the truth “as far as I can discern and declare it.”

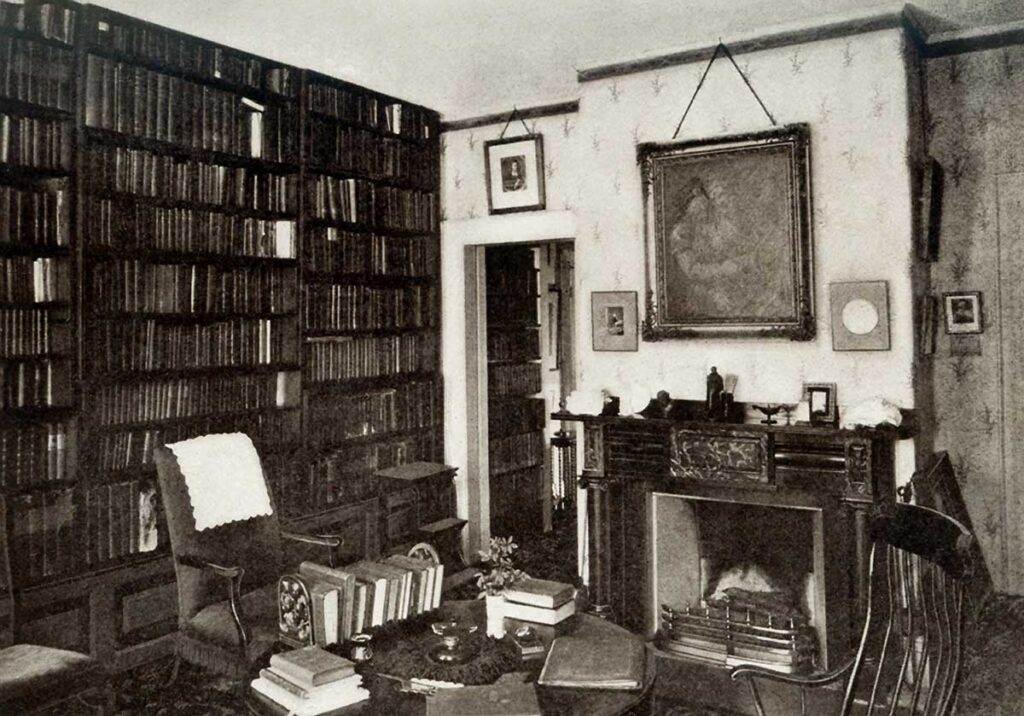

The first full-throated declaration of his new understanding was the long essay Nature (1836). Here, a powerful inwardness is matched by an intense apprehension of the material world—interpenetrating one another and pointing to a common source, in the unity of which even the most intractable oppositions can be reconciled. “In the woods,” Emerson writes, “we return to reason and faith.” And: “[T]o a sound judgment, the most abstract truth is the most practical.” A direct experience of nature and, by extension, of the divine as irradiating the things of this world will permit us to “enjoy an original relation to the universe”—befitting the citizens of an original nation. The Boston Reformer gave the book a jingoistic compliment, calling it “the harbinger of a new Literature as much superior to whatever has been, as our political institutions are superior to those of the Old World.” By then, Emerson was living in Concord—soon to gain a reputation, due to him and his cohort, as the American Athens. In the ensuing decades, as the leading spokesman of the Transcendentalist movement, he would produce there what critic James Marcus has called “a long exposure of the national psyche.”

Nature belongs on the high shelf beside Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man as one of a small handful of works that proclaim the highest possibilities for human development. For the reader, it is a spur to spiritual transformation. Already in this first book, it is true of Emerson what James Russell Lowell would later observe: that his “eye for a fine, telling phrase that will carry true is like that of a backwoodsman for a rifle.” Aphorisms like high-velocity bullets penetrate the brain before you know you have been hit.

After leaving the ministry, Emerson made his living as a lecturer—first in Massachusetts, then across New England, and eventually nationwide. Often he gave dozens of talks a year, in the early days booking everything himself, traveling by train from town to town, delivering in frigid lecture halls (above the racket of people “slambanging the stoves and coal scuttles”) his encomia to nature and human potential and the autonomy of the individual mind. Banned from Harvard after his 1838 “Divinity School Address”—which decried the church’s spiritual poverty and called for “new revelation”—he spoke chiefly in working-class lyceums, receiving from their mixed audiences mixed receptions. They found his lectures of the early 1840s “very fine & poetical but a little puzzling,” Emerson thought. Still, he relished his role. It was before such audiences, cross-sections of humanity, that he overcame what he called the “porcupine impossibility of contact with [other] men.”

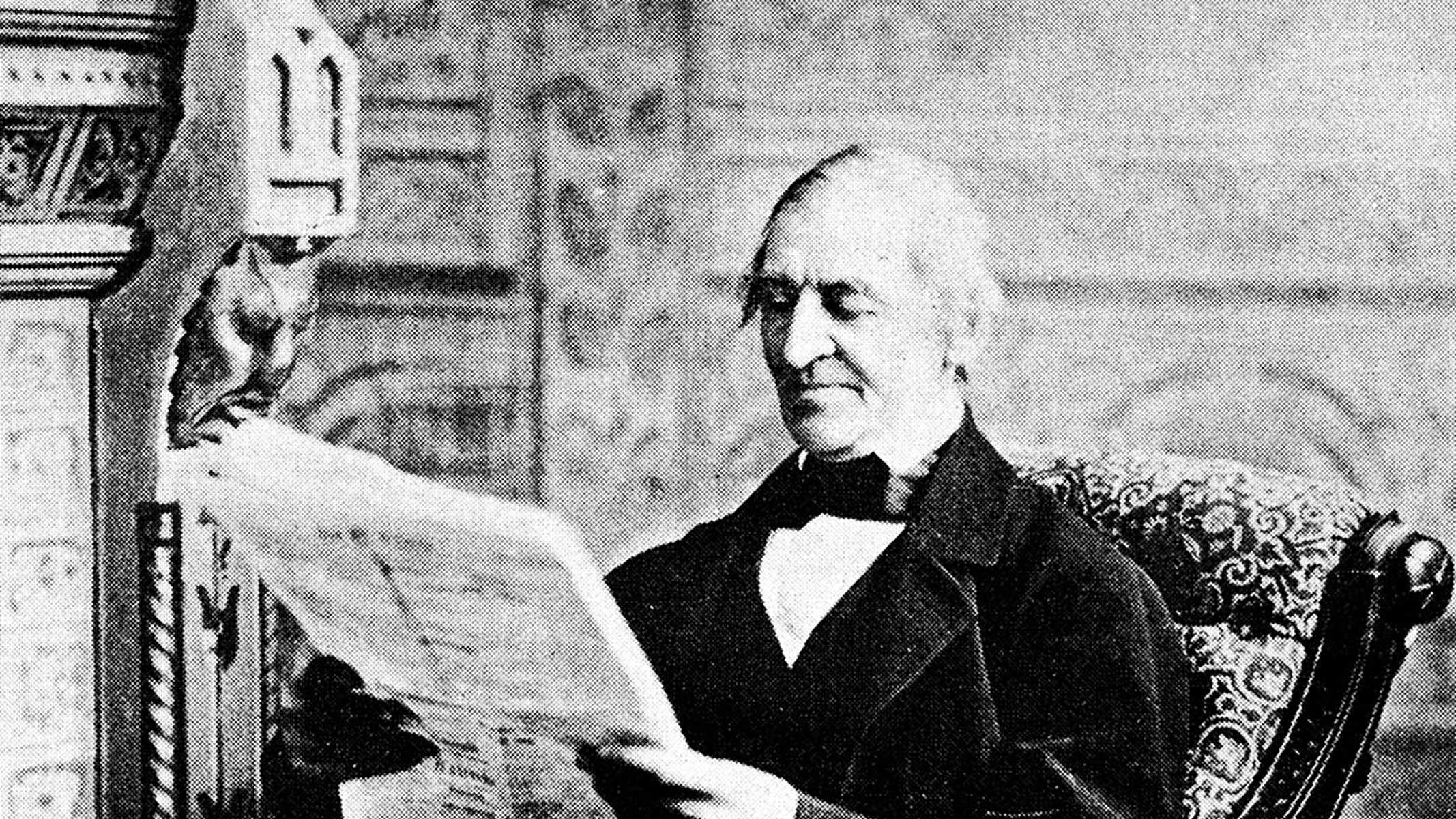

What did those audiences see? A man tall, ungainly, with large hands and the hawk-like face of a judge, inclining his body and craning his neck toward them, visible in his blue-gray eyes a “mysterious and undefinable light,” as one Cincinnati newspaper put it in 1857. “He is not graceful, but he carries a weight grace and culture alone could never supply.” His words, reported Margaret Fuller, “took root in the memory like winged seed.” Emerson at the height of his career held audiences spellbound.

The journals were a laboratory, the lectures a testbed for his ideas. Reworked and refined, they emerged as electrifying—if, at times, mystifying—essays. Until then, his Transcendentalist revaluation of values had remained within a limited coterie. At last, readers could absorb what his friends and lecture audiences had long heard. His style—now elliptical, now direct; vaporous one moment, the next crystallizing into adamantine epigram—drew both praise and scorn. “Never,” huffed The Athenæum, “was diction so rough, so distorted, so inharmonious; never was expression so opaque, so ponderous, so laboured.” But for those with ears to hear, the essays were nectar. Emerson’s voice rises in thrilling arias that sweep the reader along, as in “Circles”:

Thus there is no sleep, no pause, no preservation, but all things renew, germinate, and spring. Why should we import rags and relics into the new hour? . . . The one thing which we seek with insatiable desire, is to forget ourselves, to be surprised out of our propriety, to lose our sempiternal memory, and to do something without knowing how or why; in short, to draw a new circle. Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm. The way of life is wonderful. It is by abandonment.

Behind such perorations, as reviewers detected early on, there was no logically constructed ideology or social program. Instead, wrote the Boston Quarterly Review, Emerson’s essays “consist of detached observations, independent propositions, distinct, enigmatical, oracular sayings, each of which is to be taken by itself, and judged of by its own merits.” Yet this eccentric sage, who deems a foolish consistency “the hobgoblin of little minds,” has definite enduring concerns. His work circles a center, now at one altitude, now at another, fixing its gaze on diverse vistas—inhabiting what J. A. Baker called the hawk’s “pouring-away world of no attachment, a world of wakes and tilting, of sinking planes of land and water. We who are anchored and earthbound,” writes Baker, “cannot envisage this freedom of the eye.” Emerson could—as Blake could. A late essay quotes Blake approvingly: “He who does not imagine in stronger and better lineaments, and in stronger and better light than his perishing mortal eye can see, does not imagine at all.”

Like so many wisdom writers, Emerson preaches the fundamental unity of things—creation manifold but indivisible; animal, vegetable, mineral, and human all of a piece, “the same nature in a river-drop & in the soul of a hero.” Later, in “Power,” from The Conduct of Life (1860), this intuition yields one of his most penetrating insights: “All power is of one kind, a sharing of the nature of the world.” This becomes a bedrock conviction of the American spirit—a central, if often unspoken, metaphysic of American art. It throbs through the work of William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy. It animates There Will Be Blood, where oilman Daniel Plainview’s violent will is not so much opposed to nature’s own brutal force—which kills men and spews geysers of black crude—as allied to it. And it prompts Ahab’s crazed claim that, could the sun insult him, he could strike it in turn, “since there is ever a sort of fair play herein.” For Emerson, radical equality is woven into the deep structure of the universe: “the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one.” Microcosm, macrocosm: down the decades, this belief in essential sameness courses through the American body politic, underpinning Emerson’s and others’ support for abolition and civil rights and, in literature, igniting (among other works) the blistering late-twentieth-century poetry of Denis Johnson:

From mind to mind

I am acquainted with the struggles of these stars. The very same chemistry wages itself minutely in my person.

It is all one intolerable war.

Naturally, there is a quotation for this, too, in Emerson’s journals: “[W]ar is a part of our education, as much as milk or love, & is not to be escaped.” Wiser than his descendants, he understands that war, being inevitable, must be learned from. There is a quotation in his journals for everything under the sun; he has thought it over already; he is forever ahead of his inheritors. Herman Melville ironically caught this perennial freshness in his complaint that Emerson gives “the insinuation, that had he lived in those days when the world was made, he might have offered some valuable suggestions.”

Like the 1960s, the 1840s were one of the mad decades of American history—a time of weird crazes (for mesmerism and spiritualism, for utopian communes) and wild cultural ferment. It was a period when the old systems seemed to be wearing out, and leading intellectuals bent their energies toward building, in Emerson’s fervent words, “better houses, economies, and social modes than any we have seen.”

Natural science was beginning to reveal, across great vistas of time and space, the interconnectedness of things. Emerson and his circle read deeply in the field. The first volume of Alexander von Humboldt’s Kosmos, linking scientific knowledge to awe at nature’s beauty, appeared in 1845. Has anyone named this book as a likely inspiration for the quintessential American poet, a decade later, declaring himself—using the German spelling of the crucial word (from Latinized Greek)—as “Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos”? Emerson knew German. Already in 1832, he was writing rapturously in his journal: “Is it not better to intimate our astonishment as we pass through this world if it be only for a moment ere we are swallowed up in the yeast of the abyss? I will lift up my hands and say Kosmos.” Books on Islam and Zoroastrianism were also reaching New England intellectuals at this time, revealing the contingency—and, to some, the limitations—of the Christian and Western traditions.

Emerson was furiously active during the 1840s—lecturing across the U.S. and in England and Scotland; coediting The Dial with Margaret Fuller; speaking out against slavery and the annexation of Texas (then a slaveholding state); and publishing, in 1841 and 1844, the first and second series of his Essays, including such extraordinary expressions of his idealism as “Self-Reliance,” “The Poet,” and “Experience.” In 1845, Emerson bought land at Walden Pond, where, from white pines felled with a borrowed ax, his younger friend Henry David Thoreau would build a cabin in which to live. Emerson’s first volume of verse, Poems, appeared in 1846. Though “gently mad” himself, however, as he wrote to Thomas Carlyle, Emerson held aloof from the era’s more extreme gestures. Unlike Thoreau, he always paid his taxes. And he declined to join Brook Farm, the Fourierist commune launched in 1841 by his friend George Ripley, who—unlike Emerson—believed American society “vicious in its foundations.”

We look back astonished on this primordial mixing of elements in early America, the mental and manual powers undivorced, as in Thoreau, who made such improvements to his father’s pencil business that their graphite pencils became for a time the best in the country. A civic order was being created out of whole cloth. Concord had a volunteer fire department, charitable organizations, an Ornamental Tree Society, and edifying lectures at the Lyceum; and in this atmosphere of Yankee enterprise, Emerson’s mysticism, said Lowell, “gives us a counterpoise to our super-practicality.” From 1838 on, the task that Emerson set himself was no less than “to seek to solve for my fellows the problem of human Life, in words.”

Emerson’s eye moves effortlessly from the particular to the general, the concrete to the abstract. As the new nation was a grand experiment, so, too, he declared in an early lecture, “every man and woman on the planet [is] a new experiment, to be and exhibit the full and perfect soul”—though he added severely, “notwithstanding the extreme paucity of men who meet our judgment, our conscience, and our aspirations.” Yoking Puritanism to Stoicism, Emerson identifies the individual as the locus of change. Self-reform is a necessary precondition for social reform. Changing laws meant little if the people themselves had not been educated and uplifted. Idealism precedes action: we must “honor every truth by use.”

Thought is devout, Emerson insists, and devotion is thought. One of his “few laws” was “the perpetual striving to ascend to a higher platform.” He worked by crossbreeding (croisements was his term)—reading widely, culling, combining. His work is a tissue of quotations and allusions. “My best thought came from others,” he claimed, maintaining well into his career that he “could well & best express my self in other people’s phrases, but to finer purpose than they knew.” (The boast in that last phrase should not be overlooked.) Oliver Wendell Holmes once counted 3,393 references to specific individuals—mostly authors—in Emerson’s published writings, involving 868 different names. Shakespeare appears 112 times, Plato 81, Plutarch 70, Dante 22. “His mind,” Holmes wrote, “was overflowing with thought as a river in the season of flood . . . full of floating fragments from an endless variety of sources. He drew ashore whatever he wanted that would serve his purpose.”

The wisdom of ages was there for the taking; the ore of new discoveries was there to be mined. Like Montaigne, whom he admired, Emerson is an essayist par excellence. He soon recognized that most people paid no mind to his raw materials, but that the finished products of his studies “will sell, it seems, in New York & London.” They still do.

We find Emerson in 1855—the year of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, a copy of which is mailed to the great essayist, from whose adulatory letter of response the poet will proceed to blazon a line (“I greet you at the beginning of a great career”) without permission on the spine of his second edition—chiding himself. Some thoughts, Emerson says, have paternity and some are bachelors. “I am too celibate.” Did he think himself insufficiently prolific? Or poor in disciples? Or was he frustrated with the mixed, even skeptical, reception that his writings continued to receive? From the first, reviewers seemed determined not merely to fault but willfully to misunderstand his meditations. “We cannot remember,” the Westminster Review sniffed, “any author who has written so much on moral questions whose name is so completely unassociated with any definite doctrine”—as if it were a flaw in a thinker who wanted to liberate his audience from dead dogma that he was insufficiently dogmatic himself. As though anticipating such objections, Emerson wrote: “People wish to be settled; only as far as they are unsettled is there any hope for them.”

That Emerson was not (as he knew) a systematic thinker, that one can cite him in support of seemingly opposite tendencies or programs—both the most public-spirited and the most self-interested of actions—is part of his lasting power. The Sage of Concord was not a hoarder of certainties. (“The virtues of society,” he writes, “are vices of the saint.”) His essays are best read as spurs to further thought, not as final resting places. Like his disciples Whitman and Thoreau, he might have echoed Heraclitus: “The most beautiful order of the world is still a random gathering of things insignificant in themselves.” His essays have an ad hoc quality that feels wholly American. Yet despite his skepticism, Emerson believed that the intellectual’s task was “to look for the permanent in the mutable and fleeting.” He took the earth at its word—that it has something to teach us.

Critics and admirers alike often described him as what he most wished to be: a poet. One reviewer complained of his “point-blank contradictions; a thing very strongly said in one essay, and very strongly unsaid in the next.” But this was not mere poetic license. Emerson grapples openly with competing truths:

If we must accept Fate, we are not less compelled to affirm liberty, the significance of the individual, the grandeur of duty, the power of character. . . . But our geometry cannot span these extreme points and reconcile them. What to do? By obeying each thought frankly, by harping, or, if you will, pounding on each string, we learn at last its power. By the same obedience to other thoughts, we learn theirs, and then comes some reasonable hope of harmonizing them.

He needs to be read in context, as prescribing the tonics necessary for the times. Against tyranny and slavery he championed individual liberty, which embodies “the sacred truth that every man hath in him the divine Reason.” To the free citizens of a democratic society—who risked becoming a mob—he preached nonconformism. He wanted readers to connect the dots between divergent maxims, to do what he said in Representative Men that Goethe did: “see connections where the multitude see fragments.” Despite critics’ carping, Emerson refused to oversimplify. “He really seemed to believe there were two sides to every subject,” wrote Fuller, “and even to intimate higher ground from which each might be seen to have an infinite number of sides or bearings, an impertinence not to be endured! The partisan heard but once and returned no more.”

Emerson longed to meet—but despaired ever of meeting—a person who was not partisan, not partial, but whole and complete. He sought “catholic men,” individuals of an all-embracing character, a universal cast of mind—their physical, mental, and spiritual powers fully integrated. Even the greatest philosophers, artists, and heroes, he felt, were granted only fragments, the divine nature broken up and divided between them. He was similarly disheartened by his countrymen who used their sacred talents for profane ends: “A man is caught up and takes a breath or two of the Eternal, but instantly descends, & puts his eternity to commercial uses.”

This was to be the American pattern in life and art. By the time that Jay Gatsby—having “wed his unutterable visions” to Daisy Buchanan’s “perishable breath”—set out, in Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel, to make the fortune he hoped would win her back, he was a recognizable, if tragic, figure. In the real world, marquee Hollywood filmmakers beholden to the box office (Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg) and born novelists who, lured by the dollar signs of cinema, turned screenwriter (William Faulkner, James Agee, Alfred Hayes) cried, as the saying goes, all the way to the bank. Each famous exemplar wore the groove deeper. This was also to be the cause of much European condescension toward what the continental mind still sees as a nation of materialistic, money-minded brutes—ugly Americans, enriched not so much by a lack of finer feelings as by a readiness to make them yield a return, like any other asset. Even the airplane, that marvelous invention—the realization of man’s ancient dream of godlike flight, hymned by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry as a means of establishing direct contact with the universe—became, in America, a vehicle for hanging advertisements in midair. “[T]his great, intelligent, sensual, and avaricious America,” Emerson privately called it. Even the countercultural rebels who swerve from this pattern must swerve consciously, aware of what they are giving up.

Part of what frustrated Emerson—personally, as a patriot, and professionally, in his lifelong project—was the stubborn strain that runs like a rude tuba line beneath the nation’s nobler themes, furnishing the subject of Richard Hofstadter’s landmark 1963 study Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. Reverent accounts of the early republic often overlook how unpromising the lumpen American public must have seemed to a Transcendentalist in Boston or a Neoplatonist in New York. “People do not read much,” Emerson confides in his journal. To keep the secret of a beautiful sentence, he advises, hide it on page 102—“the hundred pages will protect it, as well as if it were locked in my safe.” The most pragmatic of idealists and most idealistic of pragmatists, he still saw his countrymen as a multitude waiting to be galvanized, “hungry for eloquence, hungry for poetry, starving for symbols, perishing for want of electricity to vitalize this too much pasture”—the dark reaches from the Eastern Seaboard to the prairie frontier one vast proving ground for any poet strong enough to sing it—even (or especially) if, in so doing, he also sang, as Whitman did, the song of himself.

The Civil War affected Emerson deeply but did not greatly alter his essential project. Nor, as an ardent abolitionist (“a minority hated by the rich class”), did he allow it to destroy his basic belief in divine justice. Following the bloody campaigns in 1863, he reassured himself: “On the whole, I know that the cosmic results will be the same, whatever the daily events may be.”

What sounds like faith is also fatalism, which enters his writings in greater measure with The Conduct of Life. Consciously he revises the chanticleer proclamations of his earlier writings: “Once we thought, positive power was all. Now we learn, that negative power, or circumstance, is half.” “Every spirit makes its house; but afterwards the house confines the spirit.” Though he never fully outgrew his optimism—he would have been a less powerful, less consummately American writer if he had—his vision darkened as he aged. In 1861, he noted: “A nation never falls but by suicide.”

Like Tocqueville, he diagnosed maladies still working their way through the body politic. This past June, as anti-immigration-enforcement riots disfigured Los Angeles—images circulating online of agitators hurling stones at police and setting driverless Waymos ablaze—I opened Emerson’s journals from 1846 and found: “The United States will conquer Mexico, but it will be as the man swallows the arsenic, which brings him down in turn. Mexico will poison us.” I turned from page to screen and saw a masked man of lupine physique standing shirtless atop a wrecked car, holding aloft, like the oriflamme of disorder itself—its red, white, and green bands bright against a black pillar of acrid smoke—the Mexican flag. Emerson’s oeuvre is full of such foretellings—not yet proven, perhaps, but impossible to dismiss as false; awaiting, like unexploded ordnance, their time to be entirely true.

Emerson’s own life was land-mined with losses. Time and again, he was forced to draw upon his extraordinary recuperative powers. His sense of the tragic deepened, death by death: his father; his beloved first wife, Ellen, dead of tuberculosis at age 20 in 1831 (months later, he opened her coffin and looked inside, as if to confirm the brutal reality); his younger brothers, Edward and Charles, also taken by tuberculosis, in 1834 and 1836; his firstborn child, Waldo, dead at five in 1842 (“I comprehend nothing of this fact but its bitterness”); Fuller, his close friend, drowned with her husband and child in a shipwreck off Fire Island in 1850, at just 40. His two remaining brothers he would also outlive. For five years, he watched the nation he had tried to inspire tear itself apart. In 1872, his house in Concord—where for years he had kept in the foyer a print of Vesuvius erupting—caught fire and burned.

A recent book, James Marcus’s Glad to the Brink of Fear, suffers from an overly strenuous effort to accommodate Emerson to contemporary liberal sensibilities, as well as from the kind of handholding and occasionally half-apologetic tone that often mar intellectual books aimed at a popular readership today. Still, its account of Emerson and Ellen’s courtship and marriage is deeply moving. Excerpts from her charming letters are all the more remarkable for having been written under the shadow of consumption. Marcus admits, “The temptation is to quote and quote.” It was first love. Their brief time together—during which her worsening symptoms soon overcame the pair’s impressive powers of denial—was, for Emerson, “the happiest and saddest period” of his life.

Emerson himself died in 1882, at 78. He had lived long enough to attend earlier that year the funeral of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who in a poem from “the heart of the young man” had declared: “Lives of great men all remind us / We can make our lives sublime, / And, departing, leave behind us / Footprints on the sands of time.” Emerson had lived the lines. He had lectured on “the uses of great men,” had devoted essays to Plato, Shakespeare, and Napoleon. He had twice met with Lincoln. In time, he became in his own right a name to conjure with, synonymous with a mode of thought—a name engraved alongside those of other canonical American authors between the Ionic columns of Columbia University’s Butler Library. His ideas of self-reliance and of nature as both hiding and testifying to deeper truths, as well as his call to “affront and reprimand the smooth mediocrity and squalid contentment of the times,” found affinities everywhere. Emily Dickinson and William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound owe him a debt, as do a series of pragmatist philosophers, beginning with William James.

We scarcely grasp how cosmopolitan Emerson was. On a visit to England in 1873, he met John Stuart Mill, Robert Browning, John Ruskin (who showed off his art collection and delivered “doleful opinions” on modern society), assorted dukes and lords, and the author of Alice in Wonderland. He knew Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, a Persian epic seven times longer than the Iliad; he read Hafez in German and the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, in French. Among the books he thought that the Concord library should contain were Plato’s dialogues, Stendhal’s novels, and Daniel Kirkwood’s study of comets. He toured Egypt; he crossed the Mississippi on foot—three times. He knew much of Wordsworth by heart; on walks, he filled his children’s ears with poetry. To the end, he lived for the “rush of thoughts,” which was, for him, the only true prosperity. Sophia Peabody, who married Hawthorne, believed Emerson “the greatest man—the most complete man—that ever lived.”

A volume of his writings, still in my possession, enriched a camping trip I took with my father and brother 20 years ago to the Smoky Mountains. Emerson’s essays, like the variegated peaks of a mountain range, persist in the present tense. They anticipated Nietzsche, Ortega y Gasset, and much of modern psychology. They anticipate us still. They await the individual who can live up to them. In them the soul and youthful sinews of America abide.

Top Photo: “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm,” Emerson wrote. (Culture Club/Getty Images)