“If we want to move forward as a nation, we have to be willing to tell the full story of where we came from.” So said Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro, responding to the National Park Service’s decision to remove signs at the President’s House Site at Independence National Historical Park as a first step toward redesigning the exhibit. In the abstract, most Americans would likely agree with Shapiro’s sentiment. But the exhibit in question did not remotely tell “the full story” of what took place in that house. On the contrary, it presented visitors with a narrow slice of history—and framed even that in a highly biased manner.

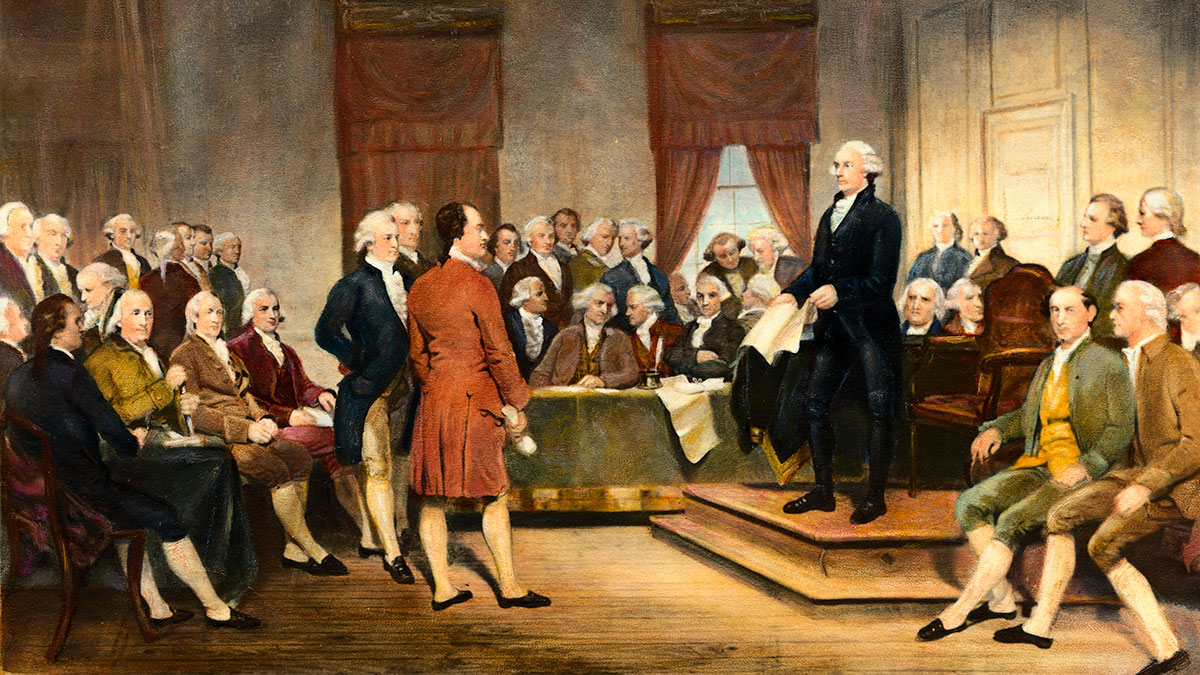

The President’s House Site marks the location where Presidents George Washington and John Adams lived and worked during most of their presidencies, before the construction of the White House. Though the house was demolished in 1832, archaeological digs in recent decades uncovered its foundations. Reporting on the Park Service’s removal of the exhibit signage, CBS’s Philadelphia affiliate noted: “Before the President’s House exhibit site . . . opened in 2010, local activists urged the creators to include information about the enslaved people who lived at the home. Those stories made it into the final exhibit.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

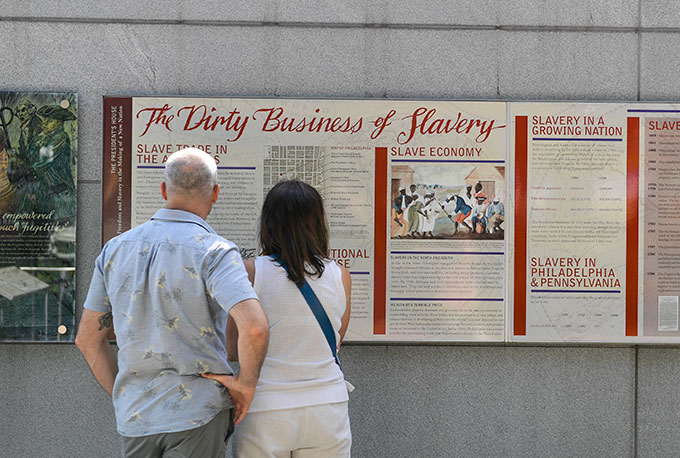

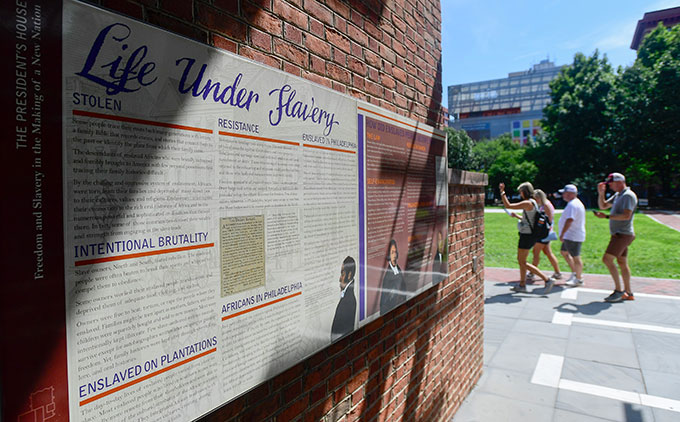

Did they ever. In fact, they were about the only thing that made it into the exhibit. As I reported in researching the site for a recent Claremont Review of Books essay, of the exhibit’s 30 signs, 25 focused on slavery or race relations.

In short, this wasn’t an exhibit about the major historical events that took place in the President’s House. As the exhibit’s removed signage conveyed, the site had “been transformed into a space that honors the lives of those enslaved” there. One wouldn’t have guessed this from how mainstream outlets have presented the Park Service’s recent actions.

This is par for the course when it comes to the progressive attempt to hijack the telling of America’s story. Leftists generally portray our history through a one-dimensional, oppressor-versus-oppressed lens, and then suggest that any effort to substitute a broader, fuller, more accurate and conventional account constitutes “whitewashing”—a term used by Governor Shapiro and others in this instance.

The site had not merely been “transformed” into an exhibit on slavery—focusing narrowly on Washington’s decision to bring enslaved people north with him—at the expense of the far more consequential events that unfolded there during the nation’s first two presidencies. It was also relentlessly disparaging of Washington.

Washington’s achievements—leading the Continental Army to victory, surrendering power, presiding over the Constitutional Convention, and governing with restraint as the nation’s first president before stepping aside again—were ignored or barely acknowledged. Nor did the exhibit offer a nuanced account of Washington’s, or other Founders’, views on slavery. Instead, its signage leveled blunt moral indictments, accusing them of “injustice” and “immorality.” Washington’s conduct was labeled “deplorable” and “profoundly disturbing,” was said to have “mocked the nation’s pretense to be a beacon of liberty,” and was discussed under headings such as “Washington’s Deceit” and “Washington’s Death and a Renewed Hope for Freedom.”

A less-biased account would have noted that, like most of the founding generation, all of whom had inherited slavery from the British, Washington sought slavery’s gradual elimination. In 1786, he wrote to John Francis Mercer, describing it as “being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by the legislature by which slavery in this country may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees.” Washington’s hope was that slavery would fade away, without causing economic ruin for any portion of the population.

Washington played a role in drafting the Fairfax Resolves at Mount Vernon in 1774, which condemned the slave trade as “wicked,” “cruel,” and “unnatural,” and called for putting “an entire Stop” to it. Later that year, he served in the Continental Congress, which adopted an agreement that the 13 colonies would “wholly discontinue the slave trade, and will neither be concerned in it ourselves, nor will we hire our vessels, nor sell our commodities or manufactures to those who are concerned in it.” As president, Washington signed the Northwest Ordinance (when it was re-passed under the Constitution), which banned slavery in the Northwest Territory (by far the most significant U.S. territory at the time), and the Slave Trade Act of 1794, which prohibited use of American ships in the slave trade.

The President’s House Site noted none of this. Then again, it did not note the Civil War, either, though it did manage, on its “Slavery Timeline,” to acknowledge Juneteenth. Nor did it observe, as biographer Ron Chernow writes in Washington: A Life (2010), that the enslaved people Washington brought to Philadelphia enjoyed “a modicum of freedom to roam the city, sample its pleasures, and even patronize the theater,” with Washington himself purchasing the tickets.

Nor did the exhibit acknowledge Washington’s momentous decision to free his slaves in his will, upon Martha’s death, or earlier at her discretion, as she ultimately chose. It also ignored the provisions he insisted be “religiously fulfilled,” requiring that the elderly freedmen be clothed and fed for life and that the younger ones be educated and taught to read. Absent, too, was any mention of Washington’s decision to grant immediate freedom to Billy Lee, his longtime valet, along with an annuity, citing their “attachment” and Lee’s “faithful services during the Revolutionary War.”

Chernow describes Washington’s decision to free his slaves as “glorious—he did what no other founding father dared to do.” (This was true at least among the Founders who lived in the five southernmost states.)

In 1860, here’s what Lincoln had to say about the founders and slavery:

[N]either the word “slave” nor “slavery” is to be found in the Constitution, nor the word “property” even, in any connection with language alluding to the things slave, or slavery; and that wherever in that instrument the slave is alluded to, he is called a “person”. . . . This mode of alluding to slaves and slavery, instead of speaking of them, was employed on purpose to exclude from the Constitution the idea that there could be property in man.

The New York Times reports that 3 million people visited Independence Park in 2023. Far more will likely visit it this year, as Americans celebrate the quarter-millennial anniversary of American independence. They deserve to see George Washington, the man most responsible for the United States of America’s existence, portrayed as a hero, not as the villain the woke Left imagines him to be. The Park Service’s recent actions at the President’s House Site take an important step in that direction.

Top Photo: Bettmann / Contributor Bettmann via Getty Images