Back in the mid-1980s, many observers considered Donald Manes, Queens borough president and chairman of the Queens County Democratic Party, a leading contender to succeed Ed Koch as mayor of New York. But in 1986, after a bizarre incident in which he was discovered bleeding in his car, apparently having attempted suicide, Manes was implicated in taking payoffs to fix contracts with the Parking Violations Bureau. A few months later, he took his life. Manes was not the only corrupt city official of his day. In the end, a dozen top city officials, including two other county leaders, and about 100 minor government employees were convicted of bribery scams and other crimes during Mayor Koch’s third term, creating the impression of thoroughgoing rottenness in city government.

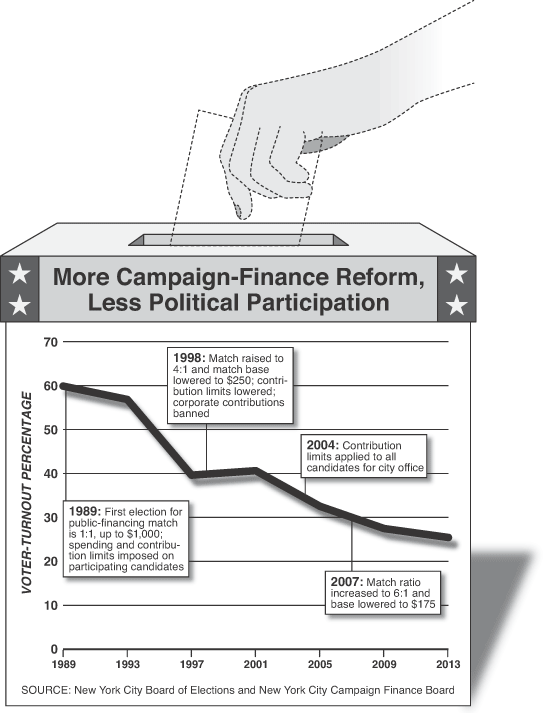

Responding to public demand to crack down on corruption, the New York City Council passed the Koch-backed Campaign Finance Act in 1988. Subsequently approved by voters in a referendum, the law established New York City’s small-donor matching-funds program, in which the government offered a dollar-for-dollar match for campaign contributions of up to $1,000 (the match applies only to contributions from individual New York City residents). Participating candidates had to abide by new limits on spending and contributions. In 2004, New York extended the contribution limits to all candidates. City officials have also amended the law to make the match ratio more generous and the qualifying expenditure smaller. Candidates today reap $6 for every $1 they raise, up to the first $175 of each donation. In 2013, 79 percent of all candidates for office participated in the public-financing program.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Now it’s Albany’s turn. Across New York State, lawmakers from both parties have been swept up in scandals involving everything from bribery to domestic violence to looting government-backed nonprofits to marriage fraud. Much of the state’s political establishment has united behind a simple cure for the corruption plague: replicating New York City’s campaign-finance reforms at the state level. Public financing, they insist, will limit corruption by increasing the amount of “clean” money in the system, and it will also help democracy, they say, by encouraging greater participation in the political process and by sparking more competitive races because better candidates will want to run.

The current enthusiasm for “public” financing far surpasses evidence of its merits, however. Under the city’s program, public corruption continues to be endemic, while voter-turnout levels have dropped to record lows and incumbents remain nearly unbeatable. Extending such a system statewide would waste money, overregulate the electoral process, and create new potential for abuse.

Just how sleazy is Albany? Recent Justice Department data show that, on a per-capita basis between 1976 and 2008, New York had the tenth-most federal public-corruption convictions and the 12th-most relative to the number of government employees. Government officials can, of course, contribute to a public impression of corruption without actually getting prosecuted for anything—and that certainly has been happening in New York. According to a July tally by the good-government group Citizens Union, “ethical or criminal issues” have forced 26 New York legislators out of office since 1999.

The malfeasance has come in many forms. In the past two years, sexual harassment accusations caused state assemblymen Dennis Gabrysak and Vito Lopez to resign from office and influenced the decision of Micah Kellner, another assembly Democrat, not to run for reelection last fall. Three other former assembly members have been caught fraternizing with interns over the last decade: Democrats Ryan Karben (who resigned in 2006) and Sam Hoyt (who stayed in office and now serves in the administration of Governor Andrew Cuomo); and Republican Michael Cole (who lost a primary in 2008). In October 2014, Queens assembly member William Scarborough was arrested and charged with abuse of “per diems,” the daily payments that legislators can collect for food and lodging in Albany. Former state senator Hiram Monserrate assaulted his girlfriend with a broken glass in 2008 and, in 2010, got caught having used a social-services agency for which he had secured government funds as his political piggy bank. Four former members of the Senate leadership have been indicted in recent years: Pedro Espada, for tax evasion and looting a government-backed medical center that he founded (convicted); the recently reelected John Sampson, for obstruction of justice and witness tampering (awaiting trial); Malcolm Smith, who lost in the 2014 primary, for trying to bribe his way to the 2013 Republican nomination for mayor, despite being a lifelong Democrat (awaiting a new trial after a mistrial); and Joseph Bruno, for taking millions in consulting fees from a businessman in pursuit of state grants (acquitted). First-term assembly member Gabriela Rosa, born in Santo Domingo, resigned last June from office after pleading guilty to two felonies: marriage fraud, in a scheme to help her establish legal residency; and bankruptcy fraud.

It’s true that some of the scandals have had a campaign-finance dimension. In addition to Monserrate, Rosa, for example, was also charged with accepting illegal campaign contributions—in her case, from a foreign donor—and Sampson was indicted earlier for allegedly embezzling more than $400,000 from sales of foreclosed properties for which he was a court-appointed referee and putting some of the funds toward his 2005 campaign for Kings County district attorney (those charges were eventually dropped). But for the most part, political contributions haven’t been central to these headline-grabbing incidents, which have sent the legislature’s approval ratings plummeting. A July 2014 Siena poll found that two-thirds of New York voters believe that Albany legislators “do what’s best for them and their political friends” and that “it never surprises me when another one gets indicted.”

Nonetheless, public financing and, more generally, campaign-finance reform have become the main focus of the push for “ethics reform” in Albany. A majority of the members of Governor Cuomo’s Moreland Commission to Investigate Public Corruption recommended public financing, and all leading state Democrats back it: Cuomo, who reiterated his support for the idea in his election-night victory speech; Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver; State Comptroller Thomas di Napoli; co–Senate Majority leader Jeff Klein; and Attorney General Eric Schneiderman. Vocal support has come from editorial pages such as the Albany Times-Union and the New York Times (“[the matching funds] program . . . is the crown jewel of New York City’s political life”) and from good-government groups such as Common Cause, the New York Public Interest Group (NYPIRG), and Citizens Union. In the 2015 budget bill, Cuomo and the legislature established a “pilot” public-financing program for the 2014 comptroller’s race, but it went nowhere. Di Napoli didn’t participate, saying that the program was too watered-down to be effective; he also boasted a strong campaign war chest, it’s worth noting. His Republican opponent, meanwhile, Onondaga County comptroller Robert Antonacci, attempted to participate in the program but failed to raise enough money to qualify.

The main opponents of public financing for New York State have been Senate Republicans, who picked up three seats in the 2014 elections, giving them a slight majority. Their gains could dim, at least for now, public financing’s state-level prospects. But the Republicans’ hold on the Senate is far from secure: two senators are over 80, and the Senate’s Number Two Republican, Tom Libous, is currently under indictment and battling terminal cancer.

The problem with public financing begins with its cost, which Republican opponents estimate would top $300 million over a four-year election cycle. Supporters put the price tag at somewhat under $200 million. Though both projections represent a small fraction of the state’s $140 billion annual budget and $64 billion general fund, the cost is still significant. And as campaign spending keeps rising, pressure will surely build to boost currently proposed matching ratios. Moreover, what governments spend taxpayer dollars on is as significant as how much they spend. Unlike public financing for, say, cleaner streets or better schools, public financing of elections provides a private benefit—serving the needs of officeholders, staffers, and consultants engaged in politics as a career.

No evidence supports advocates’ claims that public financing strengthens democracy. Even if the offer of a taxpayer match encourages more people to give money to campaigns, as some studies have suggested, donor participation remains low compared with the total voting population. In 2013, 136,370 unique donors to all candidates participated in the matching-funds program; 100,746 of these were small donors (contributing less than $250). These figures represented 3.2 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively, of all registered voters in that year’s election. And voter turnout—a more robust indicator of democratic participation—has been declining in New York City. Just 26 percent of voters participated in the 2013 general election, the lowest figure in 50 years. More people voted for Rudolph Giuliani’s losing bid for office in 1989, the first election with matching funds, than for Bill de Blasio’s winning one in 2013, even as New York City’s population grew by more than 1 million (and even as the matching ratio increased during that time). Further, studies of contributions to national campaigns show that small donors tend to be as extreme in their views as large donors, and perhaps more so—a sobering fact for those who worry that political polarization is harming democracy.

Public financing has done nothing to spur competition in New York City elections, notwithstanding claims from some former candidates that the availability of matching funds influenced their decision to run or helped them prevail. As Citizens Union found—in a report arguing for public financing—incumbent city council members get reelected at a rate close to 95 percent. To date, the only mechanism that ensures turnover in city offices is term limits, which went into effect in 2001. (Mayor Michael Bloomberg got the city council to revise the law in 2008, allowing him to serve a third term, but voters adopted term limits again in 2010.)

Even more discouragingly for campaign-finance proponents, public financing has done little or nothing to curb corruption in city government. Many participants in the matching-funds program have been implicated in one scandal or another. Public financing has even been the source of corruption. Sheldon Leffler, a former city council member, was convicted in 2003 of trying to break up a $10,000 contribution into smaller, and thus match-eligible, contributions in his campaign for Queens borough president. Council Member Ruben Wills was indicted last May for appropriating $11,500 in public matching funds by means of a shell company and nonprofit that he controlled.

Advocates stress that, when combined with other measures, such as lower contribution limits, public financing could thwart so-called legal corruption—by which they mean the power of political money, especially that donated by wealthy business interests, to purchase access to policymakers. New York State currently has the nation’s highest contribution limits (aside from the five states that allow unlimited contributions), and a NYPIRG analysis of Cuomo’s war chest released shortly before the 2014 elections found that almost half of the $45 million he raised for his reelection came from donors contributing $40,000 or more. It’s striking, though, how little influence business interests seem to wield in New York. The real-estate industry’s massive campaign contributions to Cuomo and other officials, for example, have failed to win repeal of the sidewalk scaffold law, which imposes near-total liability on developers for worker injuries, driving up insurance premiums and the cost of building throughout New York. In most state rankings of business-friendly environments, New York ranks near the bottom. In every year but one since 1977, the Tax Foundation has deemed New York’s tax regime the nation’s most burdensome. New York trails only Wyoming and Alaska in total government spending on a per-capita basis. According to unionstats.com, New York boasts a higher unionization rate than any state in both the private (15 percent) and public (70 percent) sectors. And despite the state’s abundant reserves of shale gas, which has driven extraordinary growth in North Dakota and parts of Pennsylvania and Ohio, New York has now banned fracking. “Legal corruption” appears to be a bad deal for the purported corrupters. Why the need for public financing, then?

One thing is for certain: state campaign-finance reform would mean bigger government, in the form of more regulation enforced by an expanded bureaucracy. Advocates envision a new state agency modeled on the city’s Campaign Finance Board (CFB), which administers the matching-funds program and enforces the campaign-finance law. They see the New York Board of Elections, a state body, as hopelessly incompetent. The BOE’s record is indeed hard to defend. Most egregiously, it has failed to stop lawmakers from widespread and illegal use of campaign funds for personal purposes. But the proposed remedy of a state-level CFB would lay a foundation for bureaucratic mission-creep and perhaps even worse abuses.

Consider the record of New York City’s five-member CFB. The board is officially nonpartisan: the mayor and city council speaker each appoint two members, who cannot be from the same political party, and the mayor appoints the chair in consultation with the speaker. Members serve staggered five-year terms. Despite its public obscurity and small budget relative to many other city departments, the CFB wields enormous power. Many past and future candidates for office prefer to speak off the record about it, for fear of reprisal. But what they do say tends not to be flattering, even among public-financing boosters. Peter Vallone, Sr., former city council speaker and one of the founders of the matching-funds program, charges the CFB with losing sight of its original mission, which was, in his words, “to level the playing field and keep the bad guys out of it and encourage the good guys to go into it.” An agency created to bring ordinary candidates into the system has, he says, become an obstacle to that goal because of its over-officious enforcement of campaign regulations. But what Vallone describes as the CFB’s “gotcha” disposition toward candidates is no accident. Public funding, by its nature, raises the stakes for oversight, and the CFB tends to err on the side of aggressiveness.

The most serious abuse-of-power allegation against the CFB regards its denial of matching funds to John Liu, city comptroller and mayoral candidate in 2013. Liu’s campaign treasurer and another staffer had been convicted on charges relating to a scheme involving “straw” donors—contributors who give money to campaigns in someone else’s name—prompting heightened scrutiny of the candidate’s fund-raising and leading to what the CFB claimed was evidence of other suspected violations. Liu was not accused of wrongdoing himself, but the CFB nevertheless voted not to grant his campaign $3.8 million in matching funds just weeks before the primary. With that money, Liu could have cut into front-runner de Blasio’s support, forcing a runoff between de Blasio and the centrist former city comptroller, Bill Thompson. Liu subsequently sued the CFB, which he called “a nitpicking, imperious bureaucracy,” for denying him the matching funds based on unreasonable compliance demands.

Some worry that the CFB, in addition to its pattern of overzealousness, could also begin to abuse its power in a more partisan way. “This board was appointed by Bloomberg, who didn’t have any partisan impulse at all,” says state Republican Party chairman Ed Cox—but what about a more partisan mayor? “Think of the power they have to eliminate people,” Cox says. As the recent IRS scandal shows, no agency can be insulated from the risk of politically motivated enforcement actions. In his appointments, Mayor de Blasio has not always shown appropriately arm’s-length distance in selecting officials to perform oversight roles—he nominated Mark Peters, his former campaign treasurer, for instance, to head the city’s Department of Investigations.

If New York City’s experience is any indication, tighter campaign-finance regulations won’t open up Albany politics but will instead reinforce the already-formidable power of unions in the state. Over the last 25 years, New York City’s political leadership has become more liberal, and unions stronger, with each new wave of campaign-finance reform. This isn’t surprising when you look at how the campaign-finance rules have been designed. Union contributions to campaigns in the city are legal, and each union local is recognized as a separate contributor. Corporate contributions, by contrast, have been banned since 1998. The CFB has always objected to unions’ special dispensation under city law, but politicians write the laws. Labor has the upper hand in New York State as well, so unions will likely enjoy favorable treatment in any state-level campaign-finance overhaul.

Even if state politicians disallowed New York City–style deference to unions, labor would have other means to flex its might—most notably, through independent expenditures. In today’s campaign-finance landscape, so-called Super PACs and politically active nonprofits operate outside the regulated system of campaigns and parties. The best-known outside groups are directed by Karl Rove (GPS Crossroads) and Charles and David Koch (Americans for Prosperity)—but many exist on the left, too, often with strong union backing. They emerged in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision and related rulings, which struck down restrictions on nonparty organizations while leaving in place those imposed on campaigns and parties. Deep-pocketed special interests thus have a powerful incentive to pursue their agendas outside the system, thereby avoiding many of the disclosure regulations—and all the spending and contribution limits—to which parties and candidates are subject.

In New York City’s 2013 elections, the first of the Citizens United era, unions accounted for over half of total independent expenditures, spending 40 percent more than business-backed groups, Common Cause reports. According to Governor Cuomo, the reason that the legislature failed to pass public financing for all state races in the last session was that the unions wouldn’t agree to Senate Republicans’ requirement that they stop accepting independent expenditures. That objection may have been a Republican gambit, but it cast doubt on unions’ commitment to campaign-finance reform. Both business and labor-backed outside groups were active in 2014’s closely fought battle for control of the New York State Senate, collectively spending about $14 million.

Rather than replicating New York City’s ineffective system, Albany should pursue more modest measures to fight corruption, such as focusing exclusively on legislators’ personal use of campaign funds and addressing the disclosure problems associated with the so-called LLC loophole, through which corporations circumvent state contribution limits by donating through obscure subsidiaries. Both critics and advocates of campaign-finance reform should be able to agree on stronger disclosure—the best way to fight influence-peddling through campaign donations. The Moreland Commission urged greater transparency for discretionary grants to nonprofits, or “member items”—a long-standing source of corruption at both the state and local levels. (See “Unchartered Territory,” Special Issue 2013.) Though Cuomo has cut off funding for new member items, previously authorized funding continues. The relationship between grant recipients and legislative sponsors should be more clearly highlighted, the Moreland Commission argued, and sponsors should be required to attest, under penalty of perjury, that they have no conflicts of interest connected with the appropriation and that “the funds are being directed for a lawful purpose.”

Ultimately, though, Albany needs a change of culture. “The quality of people in politics was a hell of a lot higher years ago,” says former lieutenant governor Richard Ravitch. “The problem is that no good people want to run for office.” Ravitch is right. Government policy alone can’t solve the problem of public corruption.

Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism.

Top Photo: U.S. attorney Loretta Lynch explains the embezzlement charges against Democratic New York State Senator John Sampson. (Anthony Lanzilote/The New York Times/Redux)