If New York City still retains its glitz and glamour, if skyscrapers continue to rise above its skyline, and if newcomers still see it as a springboard to betterment, then it’s worth asking how and why. That question—What makes New York what it is—was on my mind as I rushed across Fordham Plaza in the Bronx and caught a train into Grand Central, kicking off a tour of the five boroughs. My assignment: to ask five accomplished New Yorkers, one per borough, whether the city remains the place of opportunity that first drew them and their families here. And, in their view, what does effective governance look like for New York? On what metrics should new mayor Zohran Mamdani be judged as he prepares to lead a city of 8 million?

I chose the New Yorkers with whom I spoke—a community organizer, nurse, medical student, business leader, and economist—because they represent a cross-section of city residents who have achieved success. Their lives in the city have informed their views on good governance.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

George Delis’s family moved to New York from Greece when he was a year old, in 1945. By the time he was 16, they had saved enough to buy a home in Astoria, Queens. “Let me show you something,” he says, as I step off the train at 30th Avenue. Suddenly, we’re back in Greece, walking from one statue to the next—Aristotle, Sophocles, the goddess Athena herself—in Athens Square Park. “This park is one of my greatest achievements,” Delis enthuses, referring to the 30-plus years he spent as district manager of Community Board 1, during which time the park was built. Just then, a youth runs over to greet and thank him for his work in Astoria.

The connection that Delis feels with Astoria and its people helps explain the magnetic pull that brought him back after finishing college out of state. “I came straight back to New York, wanting to get involved,” he told me, drawn to “this community that was so stable and so safe.” His first role was on the New York City Youth Board, before he became district manager of the community board in 1977. “Back then, everybody was Italian—the district leaders, every elected official. We struggled to change the political landscape,” he said, explaining the resistance that some had to the idea of appointing a Greek to the community board.

But change did come, spurred first by the success of the early Italian families in Queens and then by the Greeks who arrived alongside Delis’s parents. “That first generation worked so hard, you know, doing whatever jobs they could find, and later moving out,” observed Tom Galanis, a partner in the restaurant where Delis and I sat. “It’s called moving up the ladder,” Delis replied. As those families moved out, new arrivals—from Bangladesh to Brazil—took their place, giving Queens its nickname, the “World’s Borough.” New political coalitions emerged, too, symbolized by the rise of Uganda-born Mamdani, who represented Astoria in the state assembly before becoming the city’s youngest mayor in over a century.

Asked whether Queens still offers the sense of opportunity that drew him there, Delis doesn’t hesitate. “Absolutely! Look at Mamdani—34 years old and just elected mayor. I’ve met him, you know, and he’s come to some of the community events we’ve organized here.” He scrolls through videos of the Latino, Greek, and Italian festivals that he hosts in Athens Square Park. Now 81, Delis insists that “nothing’s changed. I talk to immigrants, and so many of them come here wanting to work hard. The Greeks moved up the ladder, and now there are new immigrants—but they’ll one day be in the same situation as those before them.”

Besides his role in Athens Park, Delis was also instrumental in attracting movie production to Queens and in organizing the 30th Avenue Merchants Association. “When I was a kid, I was a real idealist,” he says. “But you have to be a realist.” Effective governance, he explains, “requires experience.” People are attracted to socialism, he says, “because they don’t yet have anything. But when they get something, they’ll think differently.” For that to happen, “stability is so important. And so are growth and responsibility. Fiscal responsibility will need to be a top priority,” along with “how safe and stable the streets become.” New Yorkers at large widely agree. An AtlasIntel poll from November found that nearly half of voters listed crime as a top issue. Mamdani can succeed, Delis believes, but he’ll “need to surround himself with the right people and listen.”

Later, I meet Lisa Borodin, a nurse and South Brooklyn native, who recounted her upbringing in the city. The daughter of Soviet Jewish émigrés who arrived in New York in the 1970s and 1990s, respectively, she recalls her childhood in 1990s New York as “extremely vivid. My mother would take me on trips to Prospect Park and Coney Island, and the city offered so many amenities, even to those with limited means.” She attended a specialized middle school before moving on to a regular public high school.

It was at Brooklyn College that Borodin fell in love with learning. “You felt so privileged to be there,” she said, grateful for an affordable education and “professors who accepted no excuses.” After earning a degree in health and nutrition, she enrolled at NYU’s School of Nursing, graduating only months before Covid-19 hit New York.

“What defines success in New York City?” I asked. “A lot of people I grew up with had parents who defined success in material terms: make a living and continuously grow it,” Borodin replied. “But I think success is feeling comfortable and knowing that the quality of your relationships is strong—that you can move in the world, able to say yes to things you want to do. And, of course, there’s a financial implication to it . . . saying yes to the movies and vacations.”

Borodin feels that such success is still achievable in New York but that “difficulties have stacked up. Life was a lot easier [in years past] in terms of cost of living.” I asked her what metrics she thinks we should use to evaluate Mamdani. “Crime has been number one for me,” she replied, adding that “the hostility of the city” is what “makes it feel so unlivable.” And, she says, “If [Mamdani] is to remain true to his message of being a game changer in bringing a new system of politics to the city, there has to be more transparency about how we spend.”

“If you strive to achieve more, you’re hit with more taxes,” she continues. “So the logical solution would be to leave New York altogether for a tax-free state and continue working and building businesses . . . in a place that doesn’t penalize you for it. If I don’t see the outcomes [in better public services], why should I give the city more money?” That’s a feeling that other New Yorkers share. In one poll, 58 percent said that they opposed making buses free, believing that it would leave “even less money to fix slow, unreliable service.” It’s a signal that the city should prioritize competence over new spending schemes.

As always, New York is in flux. “I don’t recognize the place where I grew up,” she says, though she recounts many fond memories. “To be a true New Yorker is to have a love-hate relationship with the city.”

Sanjana Venkittu moved to Manhattan after completing her studies at the University of Chicago in 2022. “On a deeper level, success for me would be feeling like I’m no longer a transplant,” she said. What keeps her here is that she “fell in love with New York very heavily. And it just so happened that the place where I had the most community involvement is also the place that wanted me most”: Weill Cornell Medicine. There were challenges in moving. “It was so much easier to get housing in Chicago.” But for her, the city’s pull endures.

Still, Venkittu worries that it has gotten much harder to become established in New York than it once was. “It’s so hard to find housing here, to have any kind of economic mobility here, when you’re struggling to make rent.” She hopes that New York’s next mayor will address disorder. “Noise pollution is unavoidable to a degree, but when there are noise ordinances [for construction], they should be enforced.” And “we could do better in limiting areas where people are allowed to smoke cigarettes and marijuana. The city should remain accessible to families with children,” she says.

I was interested to hear from Venkittu about treating mental health, given its connection with homelessness. “We’ve seen different approaches, with social workers and police getting involved with people going through crises. . . . There’s no easy answer,” she said, noting how hard it was to help those who refused assistance. If the unfortunate reality is that some might never recover from addiction and mental-health crises, the policy question becomes one of ensuring that these people don’t pose a threat to the public. But “these problems aren’t coming from nowhere,” she said. She’s hopeful that medical institutions will continue to find ways to prevent deterioration and aid recovery.

When asked how Mamdani should be evaluated in four years, Venkittu hoped that he would “genuinely stand up to his promise to be a mayor for all New Yorkers.” Viewing his youth as an asset in a city changing “in ways young people are more equipped to handle,” she said that Mamdani should also be assessed on his transparency. “I want him to say, ‘this is what I tried’ and ‘these are what steps I’m taking,’ even if he’s not successful.” (Sanjana notes that her views are her own, not her employer’s.)

A short ferry ride took me to Staten Island, where I met Joseph Conte, executive director of the Staten Island Performing Provider System, a health-care organization. “Better care, at lower costs,” he said, summing up its mission. Hazy views of lower Manhattan could be seen in the distance from his office on the North Shore.

Conte is a Staten Island native. Born in 1957, he has watched the borough grow from fewer than 200,000 residents to nearly 500,000 today, spurred above all by the opening of the Verrazzano–Narrows Bridge in 1964. “At first it was only a trickle, but then a lot of people”—including his parents—“came from Brooklyn and Manhattan,” he recalls. He remembers driving out to the island’s remaining farms to pick up produce for his father’s store and making frequent ferry trips to Manhattan.

But the “forgotten borough” faces serious challenges. Conte, whose organization works with Medicaid recipients, describes “a stubborn core of disparities”—people “stuck on public assistance, Medicaid, inadequate housing, poor schools.” He is proud, though, that his group has helped improve conditions. “We’ve trained over a thousand people over the last eight years who’ve become health aides, nursing assistants, and other health workers.” For Conte, opportunity means being able to say: “I’m standing on my own, taking care of my family, sending my kids to schools I choose, and they’re going to have a better future.”

He hopes that New York’s next mayor will bring people together after an election that “played on demographic and cultural differences. That’s not easy to knit back together.” Politicians, he continues, often promise too much. His organization’s success points to an alternative to long-term government assistance: the city might address social disparities more effectively by expanding educational and training programs that give workers in-demand skills, rather than simply subsidizing costs in ways that foster generational dependency. The preference for merit-based advancement is one that New Yorkers share: 63 percent say that they would like gifted-and-talented programs in schools expanded.

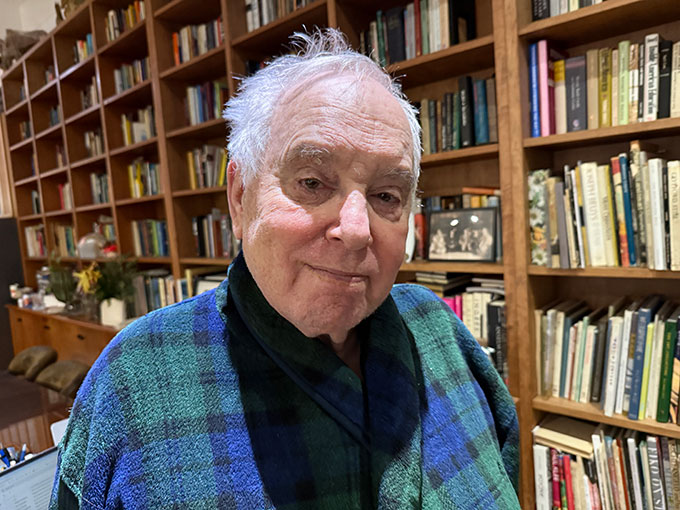

From the Bronx comes economist Gene Epstein, 81, director of the Soho Forum, which hosts lively monthly debates on social and political issues. Epstein spent his early years in the East Bronx before moving to Westchester, only to return later to the city where he now lives. “It was the romance of the city that lured me,” he says. “I felt this is where I wanted to live.”

Having moved to the suburbs as a child, Epstein recalls the contrast between the “thriving community” and “street life” of the East Bronx—where he and his friends “all played unsupervised basketball”—and the more sedate reality of White Plains, where one had to be driven everywhere.

“I had a car by the time I was 16, but I still loved the city.” Though still living with his father in Westchester, he found many occasions to visit New York. “My mother was a socialist, as was I, and I went to the city frequently to attend socialist meetings.” He was also an avid reader, and New York was unmatched for bibliophiles. “It was bookstores, movies, and live theater,” he recalled, that drew him most. After a brief stint in San Francisco, he returned to Gotham as a teaching assistant at the New School. “New York is the default,” he says, “for those who want to take full advantage of what cities have to offer.”

In his twenties, he came to see the world differently. “I’d read Michael Harrington’s The Other America and continued to associate myself with the Democratic Socialists of America,” he says, until one day, “I came across Murray Rothbard’s Man, Economy, and State, read both volumes, and finally realized there was a theory of economics I could be very excited about.” He went on to serve as the economics editor of Barron’s from the early 1990s until 2018.

I asked Epstein what he thought about the current wave of democratic socialism; Manhattan Institute polling from October found that 47 percent of Democrats in the city now identified as “socialist.” In supporting Mamdani, were New Yorkers signaling approval for state ownership of the means of production? He initially seems skeptical. “Socialists now say we need to be like Sweden,” he says; and in the public mind, democratic socialism more likely connotes the Nordic welfare model. But he warns: “I’ve debated three socialists, and they do all want the government effectively to take over the means of production.”

Gene Epstein has come far since returning to the city. His story—along with those of the four others I spoke with across the boroughs—reminds us that New York has long served as a catalyst for opportunity. Perhaps the city is not as broken as many now think. The way forward, in any case, isn’t revolution but reform—including easing land-use regulations to get New York building again, bringing spending under control, and, above all, keeping the streets safe. Effective governance will do much to keep the city vibrant for the people who continue to come here in pursuit of their dreams.

Top Photo: Astoria community leader George Delis says, “Effective governance requires experience.” (Adam Lehodey)