Since the news of Minnesota’s sprawling Somali-linked fraud cases went national, debate over immigrant crime has flared once again. President Trump has dispatched federal agents to the Twin Cities to crack down on illegal immigrants. But Trump is overreacting, critics contend: the Somali immigrant population, they claim, does not have particularly high crime rates.

Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute, for instance, set off considerable debate on X by posting a chart showing that Somali-born immigrants have, if anything, slightly lower incarceration rates than native-born Americans. Among those aged 18 to 54 included in the 2023 American Community Survey (ACS), 1,170 of every 100,000 people born in Somalia were incarcerated, versus 1,221 for the native-born.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The implication is clear. If Somalis are incarcerated at similar or lower rates, concerns about Somali crime must be overblown.

We don’t buy this argument. Nowrasteh is not making an apples-to-apples comparison. Looking at incarceration rates introduces statistical bias in a way that yields a lower-than-expected rate of Somali offending. Correcting for this, we estimate Somalis are twice as likely to be incarcerated as are similar native-born Americans.

Nowrasteh’s conclusion is starkly at odds with international evidence on Somali immigrant crime rates. In countries such as Denmark and Norway, which practice more thorough record-keeping than the United States, Somali immigrants are convicted or formally charged at several multiples of native rates. If the U.S. truly had crime rates near parity, it would represent an extraordinary and unexplained divergence. What’s in the water in Minneapolis?

There are no U.S. data explicitly measuring crime rates by nationality or country of birth. The nation’s major crime datasets don’t record immigration status. Instead, the figures that Nowrasteh and others cite on related questions come from the ACS, a general-purpose Census Bureau survey of roughly 3 million people each year.

The public ACS data report whether someone is living in “institutional group quarters,” which includes prisons but also other types of institutions such as mental-health facilities and nursing homes. This isn’t a perfect measure of incarceration, but for males aged 18 to 40 it is a very strong proxy.

Critically, however, incarceration and crime rates are not the same. Crime rates measure how often an event occurs—they are “flow” variables. Incarceration rates, by contrast, are a count of a population at any one time—they are “stocks.” Using unadjusted differences in incarceration rates between immigrants and natives to infer relative crime rates is therefore not a like-for-like comparison and can be deeply misleading.

Why? Consider a simple example: two groups of 40-year-old men, one American-born, the other immigrants who arrived in the U.S. at age 39. The groups are otherwise identical and have the same crime rates.

Will they be equally likely to be incarcerated at age 40? Obviously not. The immigrants will have had just one year to commit a crime and end up behind bars; the American-born will have had decades of opportunities to do so.

Accordingly, in this make-believe example, native-born Americans will be mechanically more likely to be incarcerated at age 40, even though the two groups have identical crime rates by design. By the same logic, their very different tenures in the United States mean that you cannot infer from incarceration rates that the immigrant group has a lower crime rate. Even if an immigrant group were to offend at very high rates, differences in tenure alone could still yield lower incarceration rates than those of native-born Americans who commit fewer crimes.

In Denmark or Norway, this problem does not arise, because crime rates are measured directly by country of origin. In the United States, by contrast, if we rely on institutionalization as a proxy for crime, we must confront its limitations head-on.

Ignoring those limits produces figures like Nowrasteh’s—which we can narrowly replicate, though the key Somali sample is very small—but which tell us almost nothing. Such results are not evidence of equal crime rates; they are artifacts of an invalid comparison. Treating the problem as negligible—or as unavoidable and therefore ignorable—does not make it go away.

To make a valid comparison, it is essential to compare people of similar ages and, in particular, to avoid contrasting lifelong Americans with immigrants who have spent only part of their potential offending years in the United States. Put simply, the latter have had fewer opportunities to acclimate to their surroundings, form criminal ties, accumulate a record, or commit serious violence—and thus to end up in prison as adults.

To do this, we follow Nowrasteh by using the ACS but also:

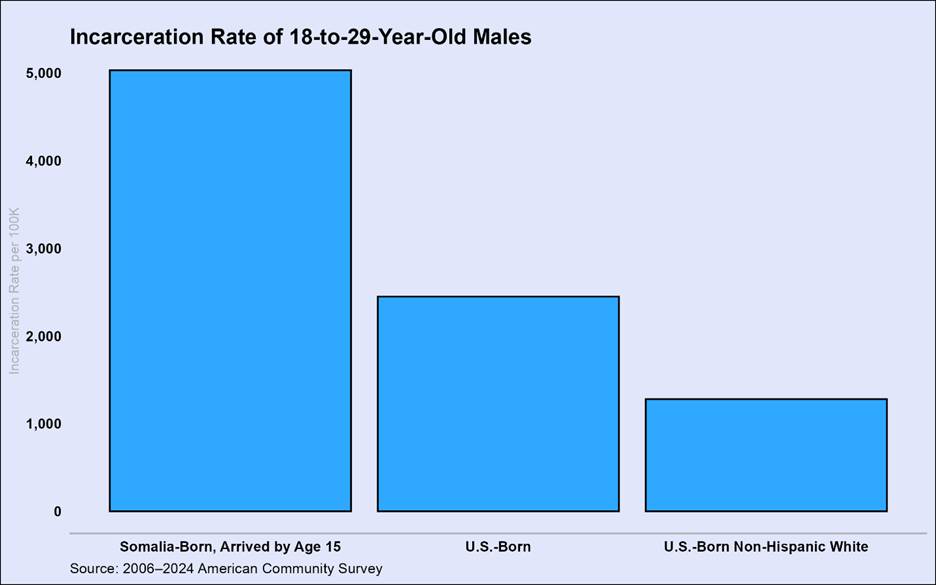

- analyze all available ACS data together (back to 2006, and through the newly released 2024 data) to increase the sample size;

- reduce sources of distortion by limiting the sample to males ages 18 to 29, for whom residence in institutional group quarters is a more reliable proxy for criminal involvement;

- and make a closer-to-apples-to-apples comparison by comparing the American-born with the subset of Somalis who arrived in the U.S. when they were no older than 15 (few adults are incarcerated for crimes committed before this age). Notably, this is also a more relevant comparison for second and subsequent generations of immigrants.

The results are striking. Under this like-for-like comparison, young men born in Somalia have roughly twice the incarceration rate of those born in the United States (5,030 versus 2,450 per 100,000). Further, incarceration rates vary sharply by race in the United States. Compared with non-Hispanic white natives (1,280 per 100,000), the Somali-born rate is nearly four times higher. Analyses of older age groups reveal similarly large disparities.

We then expand the sample to cover ages 18 to 64, while preserving a comparable framework in a more sophisticated statistical model. The model controls for year (to capture changes in incarceration over time), individuals’ exact ages (to address remaining differences in age distributions between Somalis and natives), and state of residence (to account for variation in the severity of state justice systems). Under this specification, the odds that a Somali immigrant is incarcerated are more than two and a half times those for U.S.-born males, and more than four and a half times those for native non-Hispanic whites. Given that, historically, descendants of immigrants tend to get in more trouble than the newcomers did, this is not an encouraging sign for the future.

None of this should be so surprising. Even putting aside European data, a large body of research shows that migrants do not instantly shed the behavioral and cultural norms of their countries of origin. Raymond Fisman and Edward Miguel famously showed this reality in a study measuring unpaid parking tickets accrued by U.N. diplomats in New York: officials from more corrupt countries behaved far more corruptly, even under identical enforcement conditions, and these differences persisted over time.

Alberto Alesina and Paulo Giuliano, writing in the Journal of Economic Literature, concluded that “when immigrants move to a place with different institutions, overwhelmingly their cultural values change gradually, if ever, but rarely within two generations.” Transparency International, in its Corruption Perceptions Index, ranks Somalia 179th (out of 180) in the world. Simply put, a large institutional and cultural gap exists between Mogadishu and Minneapolis.

Given the limits of the ACS, we readily concede that our analysis remains constrained and cannot estimate a precise “Somali crime rate.” Ideally, crime by birthplace or immigration status would be measured directly—but absent such data, this approach may be the only credible way to assess criminal involvement among those who arrived as adults.

What is clear, however, is that the evidence does not support dismissing public concern as innumerate fearmongering. On the contrary, under an apples-to-apples comparison that focuses on individuals with comparable time spent in the United States, Somali immigrants exhibit incarceration rates far above the native-born average.

Photo: Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images