One year ago, just after midnight on New Year’s Eve, a small brush fire broke out in Topanga State Park above the Pacific Palisades outside Los Angeles. Within hours, the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) arrived on scene and began digging handlines to stop its spread. The eight-acre fire—ignited by a 29-year-old former Palisades resident, who has since been charged with arson—was quickly brought under control. By 4:46 a.m., the department declared it “fully contained,” with “no further updates anticipated.”

But the fire was never fully extinguished. A week later, on January 7, it reignited and burned more than 23,000 acres, destroyed 6,800 structures, and killed 12 people in what became L.A.’s worst urban wildfire catastrophe.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Angelenos and others have cast blame for the Palisades Fire widely. The L.A. Department of Water and Power had kept the nearby Santa Ynez Reservoir empty for nearly a year, contributing to dry hydrants and a lack of water pressure. The LAFD’s response to the January 7 blaze was scattered and uncoordinated. Neither the LAFD nor CAL Fire pre-deployed firefighting resources to the Palisades region, despite forecasted dangerous winds and extreme fire conditions, even though a fire had just burned in the area days earlier.

But while those failures drove up the disaster’s deadly toll, new evidence emerging from a lawsuit filed on behalf of victims is revealing the many ways that California state policies may have caused the New Year’s Eve fire to rekindle on state park land in the first place—turning a tiny, containable blaze into a deadly conflagration that virtually wiped out the Pacific Palisades.

This evidence includes text messages that appear to show California State Parks employees seeking to limit the impact of fire suppression to protect endangered plants; an unreleased agency document stating that the park’s preferred policy is to let the area burn in a wildfire event; and secret maps that attempt to constrain firefighting operations in certain areas of the park—even adjacent to densely populated areas—to protect “sensitive natural and cultural resources” like endangered plants and Native American archaeological sites. It also includes allegations that state employees failed to monitor the smoldering burn scar in the days before the January 7 conflagration, despite nearly half a century of accumulated vegetation and forecasters issuing their direst warnings.

Not only was the Palisades Fire entirely preventable, the evidence suggests; it was also fueled by California state policies that, in the words of one attorney representing fire victims, “put plants over people.”

In October, a federal investigation confirmed that the Palisades Fire was not a new ignition, but a “holdover fire”—a rekindling of the New Year’s Eve arson blaze, known as the Lachman Fire. Investigators determined that the specific origin of the Palisades Fire was “a burned-out root structure at the base of dense vegetation approximately 20 feet south of the perimeter of the Lachman Fire,” just beyond the handline dug by LAFD crews on January 1, on land owned and managed by California State Parks.

For six days, according to federal investigators, the fire smoldered underground in the root systems of the park’s dense vegetation, waiting for the right conditions to resurface. The plant matter in that area hadn’t burned since 1978—nearly half a century of accumulated fuel.

The warnings were there. A State Parks ranger recently testified that she observed the ground still smoldering when she documented the Lachman Fire burn area on January 1. Hikers who visited the burn scar over the following days took photographs and video capturing smoke rising from the blackened hillside. On January 2, LAFD firefighters on the scene expressed concerns that the fire remained active. (Reached for comment, a California State Parks media representative did not dispute the ranger’s testimony but added that another employee did not see signs of smoldering, nor did two Parks peace officers the following day.)

Nonetheless, the firefighters were ordered to leave the smoldering burn scar, which sat unmonitored, even as weather forecasters issued increasingly serious warnings. By January 6, the National Weather Service issued what it called a “Particularly Dangerous Situation”—the agency’s highest alert level for fire weather. “This is about as bad as it gets in terms of fire weather,” the warning stated. Widespread damaging winds and low humidity would “cause fire starts to rapidly grow in size with extreme fire behavior.”

Why were firefighters pulled off a fire that was still visibly smoldering? And why did no one monitor the burn scar as dangerous fire conditions approached? New evidence from the lawsuit and public-records requests appears to provide an answer—one that comes directly from California State Parks’ policy.

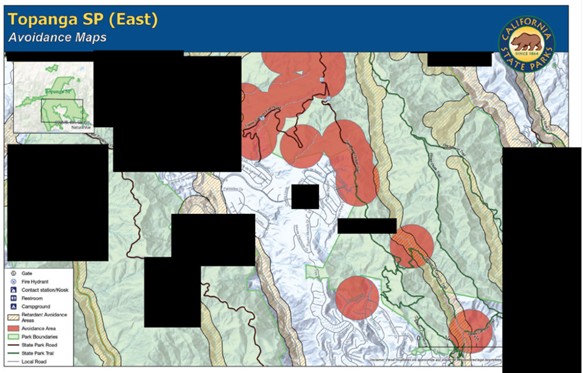

In December 2024, just weeks before the Palisades Fire ignited, California State Parks completed a draft Wildfire Management Plan for Topanga State Park. The document, obtained through public records requests by the fire victims’ attorneys, reveals a system of policies and maps designed to restrict firefighting operations on state parkland to protect “sensitive cultural and natural resources.” Those restrictions, attorneys for the Palisades fire victims allege, shaped the response to the New Year’s Eve fire.

The plan designates large swaths of the park as “avoidance areas,” where normal firefighting tactics are typically restricted. Within these zones, “no heavy equipment, vehicles, and retardant are allowed,” the plan states, and “fire suppression activities may not occur within these areas without consultation of an Agency Representative, or a Resource Advisor assigned to the incident.” The plan also says that no “mop-up” operations to extinguish smoldering hot spots are allowed in these areas “without the presence of an archeologist READ [resource advisor]”—meaning that thoroughly putting out a fire required bureaucratic oversight.

The Lachman Fire burn scar falls almost entirely within one of these avoidance areas, according to the Palisades fire victims’ attorneys.

The plan directed State Parks employees to provide these maps to fire incident commanders—but otherwise to keep them from the public. “Measures should be taken to keep the information confidential,” the document states, “including tracking and collecting physical maps and flash drives handed out, as well as ensuring that maps shared with the media do not contain sensitive resource data.”

Why the secrecy? The avoidance areas are designed to protect “sensitive resources,” according to the plan—a category that includes endangered plant species as well as Native American burial sites, village sites, and stone tool quarries. The plan specifically references populations of endangered plants within the park, including Braunton’s milkvetch, a purple-flowered legume found along Temescal Ridge, where the Lachman Fire ignited. It also requires “modified mop-up techniques” to “reduce the risk of damaging cultural resources,” instructing firefighters to “minimize spading” and “minimize bucking of logs to extinguish fire or to check for hotspots.”

California State Parks disputes the attorneys’ claim that such policies interfered with firefighting activity on the Lachman Fire. “The Lachman Fire was not in an area marked as an avoidance area, or even close to those areas State Parks considered sensitive due to the presence of archeological resources or endangered species,” a department spokesperson said in a written statement. This contention is disputed by the fire victim attorneys, who have produced maps showing the burn site within one of Topanga State Park’s avoidance areas.

Text messages between State Parks employees during the Lachman Fire, obtained through discovery in the ongoing lawsuit, suggest that these policies guided the agency’s real-time response. They also indicate employees knew the fire was burning in or near areas with endangered plants and cultural sites.

On January 1, as the fire burned, State Parks employees texted each other to coordinate their response to the blaze, including discussion of endangered plants. “I imagine they are cutting at least some astragalys [sic] with those hand crews,” said one employee, referring to the endangered Braunton’s milkvetch by its genus, astragalus. “Probably trying to improve the fire road. It’s badly overgrown just south of the fire.” The employee then texted other colleagues, “There is an endangered plant population and a cultural site in the immediate area.”

Later, another employee replied, “Can you make sure no suppression impacts at skull rock please”—a spot along the Temescal Ridge Trail near the fire’s point of origin. In another exchange, the employee voiced concern about “isolated astragalus scattered about on some rock outcrops along that south portion of the trail.”

Other messages show State Parks employees coordinating to limit impacts of firefighting operations. “There is federally endangered astragalus along Temescal fire road,” one official texted. “Would be nice to avoid cutting it if possible. Do you have avoidance maps?” The official added: “I have a couple of READs on standby. I’ll wait to deploy them until you get on scene and assess the situation. . . . Definitely will want to send them down if heavy equipment arrives.”

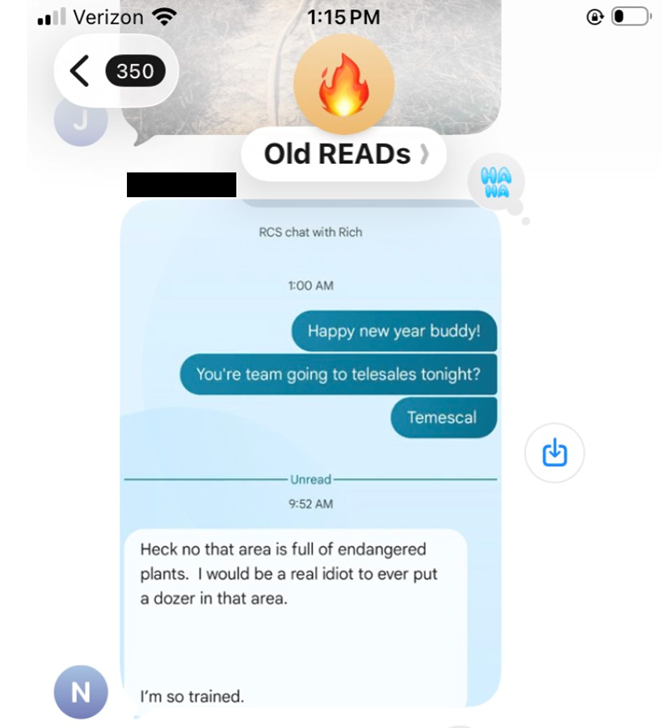

When a State Parks employee texted the LAFD’s heavy equipment supervisor to ask whether his crew would respond to the Lachman Fire with bulldozers, the supervisor replied: “Heck no that area is full of endangered plants. I would be a real idiot to ever put a dozer in that area. I’m so trained.”

California State Parks denies that its employees tried to restrict firefighting efforts. “No one from State Parks interfered with any firefighting activity (suppression or mop-up) nor influenced LAFD’s decision to not use bulldozers as part of the firefighting response to the Lachman Fire,” the department spokesperson said. “State Parks’ avoidance maps were never seen by anyone with LAFD during the firefighting response to the Lachman Fire or during the mop-up phase.”

The concern about endangered plants was not hypothetical. In 2020, Los Angeles paid $1.9 million in fines to the California Coastal Commission for damaging Braunton’s milkvetch with bulldozers while replacing power poles to improve fire safety in the area. The department was required not only to pay the fine but also to undo the grading, replant the damaged areas, and implement a long-term monitoring program.

The message to anyone operating heavy equipment in Topanga State Park—including firefighters—seems clear: damage endangered plants, even in the course of fire-safety work, and face severe consequences.

LAFD’s culture of deference to such environmental restrictions is well-established, according to Mike Castillo, a retired LAFD battalion chief with 40 years of experience in the department. “There was a fire up in 2021 in the Palisades area where we wanted to put dozers in to cut a fire road, and they said no,” said Castillo. “So, there was an understanding that it’s an ecologically sensitive area, and you better tread lightly.”

The restrictions outlined in Topanga State Park’s Wildfire Management Plan reflect a broader philosophy that explicitly prioritizes ecological preservation over fire protection, even in areas adjacent to densely populated neighborhoods. The plan says it plainly: “Unless specified otherwise, State Parks prefers to let Topanga State Park burn in a wildfire event.”

The stated rationale is ecological. “To restore the natural fire frequency and chaparral habitats, Topanga State Park should be left to burn within reasonable public safety limits and outside of fire exclusion zones.” Fire is a natural process in Southern California’s chaparral ecosystems, the plan notes, and letting some areas burn can restore natural fire regimes and promote healthier plant communities. (Asked about the justification for this policy, the State Parks representative reiterated the “public safety limits and outside of fire exclusion zones” provision.)

But Topanga State Park is not remote wilderness. It borders densely populated neighborhoods in Los Angeles. And uncontrolled wildfires are not the same thing as carefully managed prescribed burns, which are used to reduce fuel loads and mitigate extreme fire risk in populated areas.

The plan’s own risk assessment makes this policy hard to justify. The document acknowledges that “the neighborhoods of Castellammare, [sic] and Pacific Highlands along the southern border are WUI [wildland-urban interface] areas and at significant risk during a wildfire event.” It notes that “the majority of the park has not burned in over 50 years” and that “most of the Santa Monica Mountains are considered a ‘Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone’” by CAL Fire. The park’s general plan is equally blunt about the danger: “Due to local topography in the Santa Monica Mountains, fires can spread rapidly and extensively when Santa Ana winds are present.”

Yet despite this documented risk—and the park’s proximity to thousands of homes—the state park’s preferred policy was to let it burn.

“You had literally thousands of people living in homes that border Topanga State Park who were completely ignorant of the fact that State Parks had these secret policies in place to let the park burn once a wildfire broke out,” said Alexander Robertson, lead attorney for the fire victims. “It’s one thing to allow that to happen in the middle of a forest, where you don’t have thousands of homes in the urban interface. But here, in Topanga State Park, we’ve all seen the results.”

As part of this philosophy, State Parks doesn’t just try to restrict firefighting activities during a fire—it actively seeks to undo them afterward. The Wildfire Management Plan specifies that containment lines dug by firefighters must be “repaired” by spreading vegetation back across the surface. Slash piles are to be broken up and scattered. In effect, the firebreaks meant to stop a blaze’s spread are erased to restore the appearance of an undisturbed natural landscape.

Evidence produced in the lawsuit suggests that this is exactly what happened after the Lachman Fire. On January 1, a State Parks employee instructed LAFD firefighters to cover portions of the containment line with brush after the fire was declared contained—effectively undoing the firebreaks that might have helped prevent the blaze’s spread when it rekindled six days later.

California State Parks’ statewide operations manual provides guidance for park managers after a wildfire burns on state parkland: “Areas of a park unit which have burned will remain closed until appropriate Department staff have inspected the area and rectified any public safety, property, or resource protection issues.” Attorneys for the Palisades fire victims allege that state officials failed to follow these guidelines. The State Parks spokesperson said that the decision of whether to close a park after a wildfire “is up to the park’s discretion with visitor safety in mind.”

According to the LAFD incident report and testimony from state employees, a State Parks representative was dispatched to the Lachman Fire on January 1. Photographs obtained by attorneys representing fire victims also show a State Parks employee—identifiable with a jacket bearing the department logo—present at the burn scar that day, speaking with firefighters.

A State Parks ranger who visited the site on January 1 testified recently that she observed the ground still smoldering. Yet she said that she did not communicate this observation to anyone else in the department. She also testified that she did not believe it was necessary to close the park—even though the ground was still smoldering, even though the National Weather Service had issued red-flag wind warnings, and even though her agency’s policy manual required closure until public-safety issues were “rectified.”

The burn scar on state parkland sat unmonitored for six days. Hikers continued to access the Temescal Ridge Trail. No fire watch was posted. No thermal imaging was deployed to check for subsurface hot spots. And on the morning of January 7, the Santa Ana winds arrived.

Governor Gavin Newsom has called the Palisades Fire a product of “unprecedented” extreme weather, citing “record-breaking droughts” and “hurricane-force winds” driven by climate change. What he has not mentioned—and what a year of litigation and investigation has since revealed—is the role that his own state’s policies may have played in transforming an eight-acre brush fire into the worst wildfire catastrophe in Los Angeles history.

The Palisades Fire was not unforeseeable. California State Parks knew that the Lachman Fire had burned on its land. It had employees on scene within hours. It had a policy manual requiring closure, inspection, and remediation of public-safety risks. It had six days and increasingly dire weather warnings. And it had, according to its own confidential planning documents, a preference to “let Topanga State Park burn.”

The State Parks department sees it differently. “State Parks does not ‘favor plants over people’ or have authority to overrule firefighting decisions,” the department spokesperson said. “State Parks’ policies make it clear that its role during a fire is to protect human life. When wildfires occur on State Parks property, firefighting response is the responsibility of the appropriate firefighting agency. In general, State Parks’ role during wildfires is to provide firefighting personnel with information on the park’s infrastructure and resources—relevant and important information when responding to and extinguishing a fire in isolated, remote, or biodiverse wildland areas managed by State Parks.”

Governor Newsom has dismissed the lawsuits against the state as “opportunistic” and insisted that “the state didn’t start this fire.” The federal indictment supports his contention that a 29-year-old arsonist lit the match. But the evidence put forward by the victims’ lawsuit suggests that state environmental policies helped ensure that a small, containable brush fire would smolder for nearly a week, unmonitored and unextinguished, until it exploded into calamity.

Twelve people are dead. Nearly 7,000 homes and businesses are gone. And a question at the heart of this disaster—whether California’s environmental priorities have made its citizens less safe—is one that state leaders have yet to confront.

Top Photo by Apu Gomes/Getty Images