John Williams: A Composer’s Life, by Tim Greiving (Oxford University Press, 640 pp., $39.99)

The sheer breadth of John Williams’s resume is hard to absorb. The 93-year-old composer and 54-time Oscar nominee began his career in the days of Audrey Hepburn and Henry Mancini and finished his last round of Star Wars scoring in 2022, writing a new theme for Disney Plus’s Obi Wan Kenobi. Tim Greiving’s meticulous biography, John Williams: A Composer’s Life, constructed partly of interviews with Williams himself, provides the first truly comprehensive look at a career that has shaped popular American cinema.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Greiving argues that Williams, along with “populist” filmmakers George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, helped resuscitate the lush orchestral sound demoted after the studio system’s collapse in the mid-1960s. Williams was a crucial part of Hollywood’s renaissance in the 1970s and 1980s, digging cinema out of the doldrums after a decade of cultural and political turmoil.

Born into a musical family in Queens, John Williams grew up watching his father, Johnny Williams, play drums for the Raymond Scott Quintette and later become a Hollywood session player. The younger Williams, showing an aptitude for piano, originally studied to become a virtuoso. Being drafted into the Air Force disrupted his plans to pursue formal musical education—perhaps a fortunate detour, Greiving writes, as otherwise Williams might have been indoctrinated into the conservatories’ prevailing anti-populist and anti-melodic trends: serialism and atonalism. Star Wars might have sounded more like something composed by John Cage.

After his military service, Williams followed in his father’s footsteps to become a Hollywood session player, sitting in on piano for such lighthearted 1950s classics as Funny Face and Some Like it Hot. As his career gained momentum in the mid-1960s, he began arranging and composing for films and television, including the bubbly score for William Wyler’s How to Steal a Million. Williams experimented and steadily built his melodic style in the late 1960s and early 1970s, scoring such pre-Spielberg disaster yarns as The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno.

At the time, big orchestral scores were considered passé. Long-haired directors of the New Hollywood movement stipulated that scores should be sparse and avoid “emotional manipulation,” preferring raw and naturalistic soundscapes. After Stanley Kubrick used a needle-drop score of preexisting classical music consisting of Ligeti, Strauss, and Khachaturian for 2001: A Space Odyssey and George Lucas juke-boxed American Graffiti with popular 1950s hits, orchestral composers seemed permanently dethroned in Hollywood.

Greiving traces William’s rise to prominence to the period surrounding the tragic death of his first wife and high school sweetheart, Barbara Ruick, in 1974. Around this time, Williams met the young Spielberg, who had collected the composer’s film scores. Their first movie together, 1975’s Jaws, scored with Williams’s soon-legendary two-note theme, launched the composer into massive success and set the stage for his career-defining assignment: Star Wars.

For George Lucas’s operatic Gesamtkunstwerk, Williams employed Wagnerian leitmotifs for each of the film’s larger-than-life characters, recalling the lush classical scoring of Erich Korngold. Like Williams, Lucas was inspired by the heroic adventures of old Hollywood, by matinee serials such as Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, and by the ideas of mythologist Joseph Campbell. Some critics dismissed Williams’s score for Star Wars as manipulative Mickey Mousing—“overscoring” every moment with musical cues and variations on leitmotifs—but the 1977 blockbuster, with its archetypal characters set in an ancient society in outer space, proved a sensation.

To this day, Greiving argues, classical music elites dismiss Williams as a second-hander cribbing from Gustav Holst’s The Planets, Beethoven, Korngold, and others. Greiving takes a more balanced view, noting how Williams drew from a variety of sources, employing sounds and motifs that stir an audience’s melodic consciousness. Just as Lucas constructed Luke Skywalker’s hero’s quest as a mythical archetype, Williams mined cultural memory to infuse the archetype with a melodic identity.

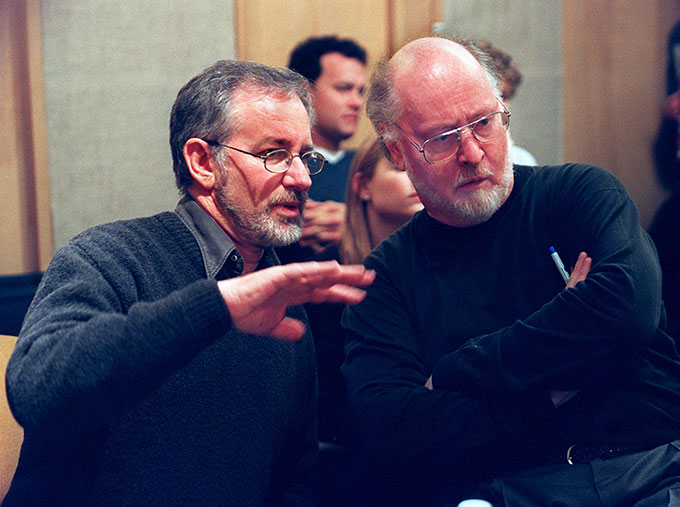

Though Williams would score the many subsequent Star Wars films for the rest of his career, his collaboration with Spielberg was arguably more pivotal, steering popular cinema away from Hollywood’s post-Watergate cynicism with Close Encounters of a Third Kind (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and Jurassic Park (1993), as well as more serious films like Empire of the Sun (1987), Schindler’s List (1993), and Saving Private Ryan (1998).

Of Williams and Spielberg’s complementary artistic visions, Greiving writes:

where most of his classmates of the Hollywood New Wave had a sour outlook, Spielberg found sweetness. That flavor was saccharine for some filmgoers, but one reason he and John became unshakably simpatico was that John, too, saw mostly sweetness and nobility in the world. John scored a handful of cynical films in his long career, but he gravitated toward the romantic and the redemptive—qualities embodied by the films of Steven Spielberg.

Much like director Alfred Hitchcock and composer Bernard Hermann, Spielberg and Williams saw their careers become intimately tied. As recently as 2022, Williams provided a humble score for Spielberg’s semiautobiographical film, The Fabelmans.

Williams’s success has helped legitimize film music in concert halls, Greiving observes, especially given his long tenure as conductor of the Boston Pops, though the composer was a controversial choice to lead the orchestra in 1979, when he succeeded Arthur Fiedler. In this role Williams expanded his repertoire, composing concert pieces more modernist in style. These works may not prove as enduring as his film scores, but they yielded collaborations with cellist Yo Yo Ma and violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter. Greiving shows how Williams ultimately earned the respect of many classical musicians.

Greiving’s biography offers an in-depth look at Williams’s creative process and traces his considerable influence on film scoring. The prolific composer, he argues, returned optimism and grand symphonic mastery to American cinema. Whatever the critics might say, that is legacy enough for any musician.

Top Photo by Shannon Finney/Getty Images