I walk alone through almost every neighborhood of Istanbul, often at night. This is a megacity of at least 12 million people, many of whom are poor and three-quarters of whom are under 35. Income distribution is gravely unequal. I am nonetheless less afraid—much less afraid—that I will be a victim of violent crime here than I am when I walk through London, Paris, or any big American city.

Istanbul’s streets don’t feel menacing. I rarely see drunks and never see crackheads, gangs of feral youths on street corners, or tattooed louts on the subways and buses. The panhandlers inspire pity, not fear. True, in some neighborhoods, the glue-sniffing street kids are dangerous; in others, hookers attract a louche clientele; pickpockets operate near the tourist attractions. But in the four years I’ve lived here, I’ve heard few firsthand stories of violent crime. The International Crime Victims Survey (ICVS), a worldwide poll of householders’ experiences with crime, confirms my impression that Istanbul is an exceptionally safe city. But perusing the ICVS data, I noticed something so odd that I mentioned it en passant to the editor of this magazine. “According to the ICVS,” I said, “Istanbul has the lowest rate of assault in Europe . . . but the highest rate of burglary, higher even than London.” I signed off with an innocent, “I wonder what this means?”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Alas, I was about to find out. Only a few weeks later, I woke up to find my front door ajar. My desk drawers and jewelry box were open and the contents of my handbag carefully laid out on a cushion. The cash in my wallet was missing. My great-grandmother’s wedding ring was gone. The burglar, who had picked my front-door lock, had taken pains to be considerate, by Western standards of burglary. He had not harmed me; he had not woken me; he had not made a mess; he had taken only the cash and the gold and left behind, thank God, my computer, bank cards, passport, and some costume jewelry to which I’m sentimentally attached. He had slipped out again as silently as he entered.

When I told my friends what had happened, almost all replied that they or someone they knew had recently been burgled, some more than once in the past year. When I had an alarm system installed, the workmen told me that business was great. Turkey, like the rest of the world, is suffering from the global economic crisis. No one else here says that business is great. All this seemed to confirm what the ICVS suggested: that in this exceptionally safe city, burglaries are exceptionally common. But why?

Beyond the ICVS, I could find no solid statistical support either for my sense that Istanbul is very safe or for the contention that it has a serious burglary problem. For inscrutable reasons, the Turkish government no longer makes Istanbul’s crime statistics available to the public. Every official in every office I petitioned—from Istanbul to Ankara and back again—claimed not to have the authority to release the statistics, then referred me to another office. This went on for weeks until I realized that it was a polite way of saying, “Get lost.” I doubt the government is trying to hide anything; it’s just the Turkish way. The idea of an open society hasn’t yet taken hold here, and the reflexive official answer to any question is no.

Until 2007, official figures were published, but they were largely incomprehensible. There were no definitions of the offenses in question, which included “bad treatment” and “forestry crimes.” The Turkish press recently reported that the Istanbul Police Department recorded 150,000 crimes last year: where they got the number remains unclear, but if accurate, it would confirm my impression that Istanbul is unusually safe. Police in London, by comparison, recorded nearly 1 million crimes last year. But keep in mind that Turks are less likely to report crimes to the police than Britons and that many crimes here are not legally defined—or popularly understood—in the same way.

Turkey does not conduct a national crime survey. Turkey’s former interior minister and head of Istanbul’s Police Inspection Board, Sadettin Tantan, tells me that he cannot even begin to estimate the dark figure of crime in Istanbul—the real crime rate, as opposed to the recorded one (see “The Dark Figure of British Crime,” Spring 2009). “Twenty or 30 years ago,” he says, “the police had a pretty good idea how high the dark figure was, but Istanbul’s population has exploded so massively since then, and its demographics have changed so much, that now the number is incalculable.”

The ICVS at least has the virtue of using consistent methods from country to country. If taken at face value, its findings are remarkable: only 3.5 percent of Istanbul’s respondents said that they had been victims of an assault over the last five years, but 30 percent claimed to have been victims of a burglary or attempted burglary. Data from the ICVS and similar surveys show that Istanbul is far safer from violent crime than other megacities in the developing world, like Rio de Janeiro, Lagos, and Karachi. The only cities of comparable size and similarly low crime rates are in East Asia—Hong Kong and Shanghai, for example—and they are quite developed by comparison.

The ICVS polled only 1,242 Istanbul residents, and it surveyed householders, not squatters; since Istanbul has massive neighborhoods full of squatters—some estimates place the number as high as 60 percent of Istanbul’s total population—the data are nothing more than suggestive. Still, what they suggest is consistent with my general impression and direct personal experience. You are far less likely to be mugged, knifed, threatened, robbed at gunpoint, assaulted, raped, or murdered here than in other cities of this size. But unless your home is protected by iron window spikes and slavering Dobermans, you can kiss your great-grandmother’s wedding ring good-bye.

What could possibly account for this? If Istanbul’s crime rate were low across the board, and not just in violent crime, the question wouldn’t be difficult to answer. Istanbul’s residents are religious, their values are traditional, their families are intact, they don’t drink much, they keep an eagle eye on their kids, they are nosy, their streets are busy, and if they see someone committing a crime, they beat him to a pulp. It’s a near-perfect crime-fighting formula.

Start with religion and values. Turkey is officially secular, but 99.8 percent of its citizens are self-identified Muslims, and almost all believe in God. Turkish culture is obsessively preoccupied with honor, and to be seen as a criminal is immensely shameful. Tantan describes the stigma attached to crime: “If you commit theft, there’s no way you can ever walk around again or show your face, even to your family or the people closest to you.” Every Turk with whom I have spoken agrees.

Next, Turkish families. Only 6 percent of Turkish marriages end in divorce—as opposed to roughly 55 percent in the United States—and 90 percent of Turkish households are either nuclear, with both parents in the home, or extended by grandparents and other relatives. If the extended family doesn’t live in the same home, it usually lives nearby. Only a tiny minority of children are raised by single parents; having a child out of wedlock is shameful, and so is permitting one’s elderly parents to fend for themselves or putting them in a group home. Given what we know about the propensity of single-parent households to produce criminal offspring in the West, it’s hard to doubt the connection between Turkey’s intact families and Istanbul’s (mostly) low crime rate.

Moreover, out of both custom and economic necessity, children here tend to live with their parents until they get married. Parents consider it their right and duty to decide whether their children’s friends are suitable and to know where their children are at all times. As a consequence, unsupervised young people tend not to roam the streets at all hours. And if they are on the streets, at any time of the day, they’re sober. Alcohol is not alien to Turkish culture—old Turkish poetry is replete with references to wine—but most Turks, especially if they are pious, do not drink much. Public drunkenness, which is considered shameful, is extremely rare.

People in Istanbul watch, judge, and look out for one another in a way that people don’t, for example, in Paris, where I lived for five years without knowing my neighbors’ names. Istanbul is a city of busybodies—another reason for the rarity of violent crime. If I so much as drop a heavy dictionary on my floor, the shrieking hysteric who lives below me will be at my door in seconds to investigate.

I am friends with a martial-arts instructor whose apartment is in a poorer, conservative neighborhood. When he started giving lessons there, the neighbors called the police. They had seen young men going in; they had heard grunting and thumping; and they had seen the same men leaving, sweaty and exhausted. They came to the obvious conclusion: he was running a whorehouse. My friend knew that he would never be able to convince them that everything was aboveboard, and knew as well that if it continued, they would lynch him. The words “mind your own business” would have been useless. He moved the lessons elsewhere. As that story suggests, Istanbul has what Tantan calls “a culture of safety.” Obnoxious, even oppressive, this constant meddling nevertheless has a bright side: a Kitty Genovese story in Istanbul would be hard to imagine.

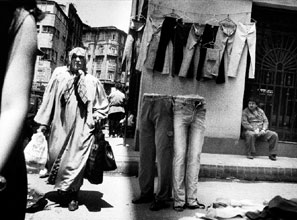

The density of Istanbul’s population and the vibrancy of its street life also ensure that potential wrongdoers are unlikely to escape the eyes of its inhabitants. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs famously described the role of sidewalks in ensuring public safety: “There must be eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to what we might call the natural proprietors of the street. . . . The sidewalk must have users on it fairly continuously, both to add to the numbers of effective eyes on the street and to induce the people in the buildings along the street to watch it in sufficient numbers. . . . Large numbers of people entertain themselves, off and on, by watching street activity.”

Jacobs might have been describing Istanbul, whose sidewalks bustle with commerce. Almost every street in Istanbul is lined with small grocers and shopkeepers. They stand on the sidewalks most of the time, even in cold weather, socializing with one another and keeping watch over the neighborhood well into the night. They know who belongs and who doesn’t. When I walk down my street, five or six shopkeepers greet me, know me by name, ask me how I am, and would doubtless defend me if I found myself threatened or harassed. Turkey is patriarchal, but in this regard it’s also chivalrous.

That patriarchal culture—along with the low rates of female employment to which it gives rise, especially among older women in more religious and conservative families—also contributes to the city’s safety. Stuck at home, many of these women are frustrated and bored. Not only do they mind their children’s business; they mind everyone else’s. Having nothing better to do, they spend their lives looking out their windows and squawking excitedly if they see anything amiss. (Before drawing overly positive conclusions about shame-based, patriarchal cultures, note Amnesty International’s estimate that at least a third, and perhaps as many as half, of Turkey’s women are victims of domestic violence.)

A final, and critical, ingredient in Istanbul’s safety is vigilantism. If you commit a crime and get caught, odds are you’ll get a good thrashing. Not long ago, I was sitting at an outdoor café when a disheveled man wandered by, arguing madly with imaginary demons. For some reason, he felt moved to grab a handful of garbage from a nearby bin and throw it at a table of diners. The owner of the restaurant charged over, beat him savagely, then grabbed him by the collar and threw him into the busy street, where only luck saved him from being hit by a car.

I’ve seen this sort of thing more than once, and it is not pretty. This kind of justice is neither blind nor merciful. Taking the law into one’s own hands is just as illegal, on the books, in Turkey as it is in America, but the cops tend to look the other way when it happens. When I reported that my apartment had been burgled, I asked the police officers at the station what the law would have allowed me to do, precisely, had I woken up and confronted the intruder. “The law says you can defend yourself with proportionate force,” said one detective in an officious, pencil-pushing way. Then his tone grew sly. “But if he got frightened and tried to flee—off the balcony, say”—my balcony is five stories from the ground—“well, these things happen!” He chuckled, and so did all the other cops.

All this helps to explain why violent crime in Istanbul is relatively uncommon. But what about the city’s high burglary rate? Quite a few people here blame the police for it. When I asked acquaintances whether I could expect the police to recover my stolen goods, their typical reaction was laughter. Many added that they believed the police to be working with the burglars. Members of my boxing gym, the men who installed my alarm system, the locksmith who changed my lock—all told me this confidently.

On the one hand, the theory sounds like typical Turkish conspiracy-mindedness: plenty of people here also believe that Jews received advance notice of the World Trade Center attack. On the other, the police certainly were dismissive when I first reported my burglary. They told me to go to a different police station, and when I did, the officers there told me that it was too late to do anything. When I persisted, they said that I should report the crime to the prosecutor, not to them.

All the same, I’m inclined to decide in favor of the cops. I spent the better part of a day at the police station trying to coax them into action, and perhaps because they grew fond of me and my amusing American questions, they finally sent a pair of superbly gruff, hard-boiled detectives to my apartment to examine the crime scene. Watching them, I began to see things their way. The detectives were careful and professional, but I had waited too long to report the event, and it was too late to obtain useful forensic evidence. I had thoroughly cleaned the apartment by then. Had I reported the theft immediately, they might have found fingerprints that matched a known criminal’s. If they had found them, the detectives said, they would have had a decent chance of making an arrest, though the stolen property would have been fenced too quickly for recovery. So from their point of view, I had asked them to waste an entire afternoon on a crime that would only add to the number of unsolved cases on their books.

Afterward, I had to return to the station to sign a statement. Even gruff, hard-boiled Istanbul detectives can’t long resist the national impulse to be friendly to foreigners, and they offered me a ride there in the back of their mobile forensics lab. At the station, they offered me tea and settled in for a chat. People didn’t report crimes, they said, because they didn’t trust the police. Consequently, the detectives couldn’t solve crimes, and their reputation suffered further. They clearly felt aggrieved, and I could see why.

The station had an Istanbul-noir feeling: cigarette-smoke-stained walls, old-fashioned portable typewriters, stacks upon stacks of files and reports, an ancient portrait of Atatürk, in full military regalia, on the wall. There were iron bars on the windows. Why, I asked naively, did they need those? Who in his right mind would try to burgle a police station? One detective looked at me as if he couldn’t believe I’d asked something so stupid, then patiently explained that the bars were to keep criminals in, not out.

After telling me about confessions they’d extracted and murders they’d solved (in one case, they claimed, through a single fingerprint on a package of tissues), they began complaining that even when they caught a criminal, the courts swiftly released him. This is what cops say everywhere (and it tends to be true everywhere). But according to Tantan, the problem has become particularly vexed of late in Turkey and contributes to the popular perception of police corruption. “The real problem here is that there are serious gaps in the legal framework for fighting crime,” he says, sighing. “People believe that the police are cooperating with the burglars, for example, because they see the police catch a thief; they see the police collecting evidence; then they see the thief slapped on the wrist or not convicted at all. They conclude that the problem is police corruption, when in fact the problem is the legal system, which is too tolerant of petty crime. A thief can be taken to court without ever being taken into custody, then released without spending so much as a day in jail.”

This isn’t what you’d expect to hear in a country made infamous by the movie Midnight Express, but it’s plausible. Turkey is trying to join the European Union. To meet the Copenhagen criteria—the rules governing membership eligibility—the Turkish parliament has passed extensive legal reforms aimed at protecting human rights. Though police brutality remains widely reported, the death penalty is no more, and the military’s control over civil justice is severely attenuated. New courts of appeal have been created. Time limits on police custody and pretrial detention are significantly shorter. A zero-tolerance policy on police torture has reduced the prospect of impunity for police officers who coerce confessions. Detainees now have a guarantee of immediate access to a lawyer and financial aid, and statements taken in the absence of counsel are largely inadmissible in court.

The new legal code makes it harder to put an innocent man behind bars. Inevitably, this makes it harder to put guilty men behind bars, too. “There are a lot of seemingly strange aspects of the legal code that leave the public perplexed and angry,” says Tantan. “For example, when a bank guard recently killed a bank robber, he had to stand trial and go through the whole court process, even though it seemed obvious to everyone that the bank robber had it coming.” It’s not surprising that Turks reach for the idea of corruption to explain these things. Corruption is a much more familiar concept to the average Turk than presumption of innocence.

We’re still left with the burglary mystery. Social controls that militate against crime generally, one would think, would also militate against theft. Tantan offers a theory. “There is a huge amount of migration through Istanbul,” he says. “A lot of petty crime is committed by migrants who need money or drugs. But a lot of petty crime, too, is committed by PKK juveniles.” The PKK is a radical-left-wing, Kurdish-separatist terrorist group; Turkey has been at war with it since the 1970s.

“The PKK dominates Istanbul’s petty-crime scene,” Tantan continues. “Gangs of thieves and burglars are working under the PKK’s influence. They’re young kids brought in from the southeast to beg, pickpocket, and steal. Petty criminals in Istanbul work on a neighborhood basis. Whoever controls the neighborhood usually has to kick up a portion of the proceeds to the PKK. The police and gendarmerie try to track down the top figures in the neighborhood, the ones with direct links to the PKK. In areas where they’re successful, you won’t find petty crime.”

There is a tendency here to ascribe any unfortunate event to the PKK, so my first response to this was incredulity. But it’s undoubtedly true that the PKK is involved in organized crime. There is widespread consensus among intelligence agencies that it engages in racketeering, extortion, and human trafficking; it is also said to control the majority of the drug trade between Central Asia and Western Europe. So perhaps it is not so ridiculous to hypothesize that it’s doing a sideline in burglary. And Turkish legal scholar Necla Güney agrees with Tantan that the PKK has “established itself Europe-wide as a narcotics dealer, a racketeer and a large-scale burglary organizer.” The group has the motivation to steal: it needs cash to finance a war. It certainly isn’t constrained by ordinary social controls; after all, it regularly bombs crowded shopping centers and assassinates doctors and teachers.

And it would make sense to use juveniles to do it. The rights of children have been at the top of Turkey’s legal-reform project: it is now nearly impossible to incarcerate them here, just as it is in Europe. Obviously, the protection of children is a welcome development, but it also creates a perverse incentive for criminals to exploit them: even those children who are caught red-handed can be back at work the next day. In response to the question, “Why burglary, but not mugging?,” could the answer be that kids simply aren’t very good at mugging adults? They’re terrific little burglars, though—they can get through windows that adults can’t squeeze through. They’re light, so they can climb stairs and pad through apartments without waking people up.

If my meddlesome neighbor had seen adults casing the building or loitering in the hallways in the middle of the night, no doubt she would have made noise and woken the whole neighborhood. Had she found a strange child, however, I daresay her first response would have been puzzlement or concern. A child could easily exploit her confusion to escape. That advantage might explain why the thief in my apartment took his time—carefully sorting through my jewelry box for the gold, for instance, instead of just throwing the whole thing into a bag. My first thought—a chilling one—was that he had felt confident in his ability to handle things if I woke up. But on reflection, is it possible that he believed not in his ability to harm me but in my unwillingness to harm him? Turkish vigilante culture would never extend to throwing a child off a balcony. Further, everything the burglar took was light. An adult could make off with a television set easily—but could a child?

When I asked the cops at the station, they agreed with Tantan’s theory. Most burglaries, they said, were committed by highly skilled juveniles who were kicking up the proceeds to organized criminal gangs, especially those run by the PKK. They also agreed that efforts to bring Turkey into compliance with EU legal standards had made it impossible for them to put these miserable kids behind bars. No one, however, was able to give me proof that the PKK connection was real. I asked Tantan for evidence: Might I consult court filings, prosecutors’ briefs? I was told that they were closed to the public. Could I interview a convicted burglar? I would have to ask the chief prosecutor for permission. He declined to speak to me.

It would be credulous to accept the PKK theory without reservations. The Turkish government is at war with the group; neither it nor the police are neutral analysts, and the allegation clearly serves definite political aims. Still, I have heard no better explanation for Istanbul’s curious burglary wave—or any other plausible explanation, for that matter. And thus I have reluctantly concluded that, strange as it sounds, it is indeed possible that Maoist-Kurdish-separatist-PKK-slave-urchins stole my great-grandmother’s wedding ring.

Just as I was finishing this article, burglars attempted to rob my building again. They were thwarted by my neighbor. She heard a suspicious noise, ran upstairs, saw two teenagers she didn’t recognize, and demanded to know who they were. Their response sounded fishy to her: she began screaming. Other neighbors ran over immediately, but they were too late. The kids escaped. When the police arrived, they told me that they had arrested six juveniles for burglary in my neighborhood in the past week alone.

They firmly expected that they would all be back on the streets within days.