A decade ago, the United States and much of the West descended into an economic crisis caused by excessive debt. Americans had simply borrowed more than they could afford to repay. The debt, though, masked more complex long-term problems. Due to upheavals caused by both global trade and technology, for example, working-class and middle-class workers hadn’t received raises adequate to keep up with the rising cost of living. The extra debt—fueling the purchase of houses, cars, and consumer goods—allowed people to keep spending as if they had more money.

This mountainous debt was the product not of markets but of government planning. The United States, on a bipartisan basis, had long encouraged its ever-larger financial firms to keep lending, mostly because neither political party wanted to address the deeper economic problems confronting workers. Starting in 2007, free markets—or what was left of them—tried to warn the planners: their way of doing business had failed, and the U.S. couldn’t keep it up. That year, lenders began to pull back, their appetite for risking money on lower-quality borrowers dwindling. The next year, lenders cut off the debt flow entirely, and the global financial crisis began. As markets suddenly regarded much of the nation’s private debt—chiefly mortgages but credit-card and auto-loan debt, too—as less likely to be repaid, the firms that had dealt in that debt began to topple.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The financial crisis would have caused lots of pain no matter what governments did in response. But leaders took what may turn out to have been the worst course of all—and one that could ultimately cause even more pain: trying to solve a debt crisis by creating yet more debt. In doing so, they have, at best, suppressed and, at worst, destroyed the vital signals that financial markets send about excesses and scarcities, risks and rewards.

When no one knows what anything is worth—a fair statement describing financial markets today—no one can know what, rationally, to invest in. Irrational investments, in turn, result in a less productive economy. Regardless of the policymaking goal—whether it’s higher-paying private-sector jobs or more public-sector social spending—this outcome is untenable.

Few people think much about the hidden infrastructure of a free-market economy: the stock and bond markets and the commodities markets for raw goods, such as oil and gold. These trading and investment markets determine prices. If investors believe that prospects for a company are good, they’ll purchase its stock, and thus increase the stock price, rewarding earlier investors who first saw the firm’s potential. Higher oil prices, in turn, can spur needed investment in complex energy-development projects; lower iron-ore prices can lead firms to close unproductive plants. Markets aren’t perfect: they’re prone to herd mentality and bubbles and can be manipulated. But the imperfect information they provide is far better than nothing.

Global bond markets play a particularly critical role because their activity affects all other markets. Money borrowed in bond markets gets invested in other assets, such as property, or in resources, such as factory equipment, that create jobs. Dysfunction in bond markets can thus wreak havoc with the global economy.

When firms or individuals buy bonds, they’re lending someone else money. In turn, the company or person who sells the bond (usually through an investment bank) is borrowing money. When more investors want to buy bonds than sell them, the price of the bonds goes up, and interest rates—the annual percentage that borrowers pay on their debt—fall. When more investors want to sell bonds than buy them, the reverse happens: the price of the bonds goes down, and interest rates go up, because fewer people want to lend money.

What causes investors to change their assessment of whether to buy bonds or to sell them, and consequently to help lower interest rates or raise them? First, they look at expected government behavior. The Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, sets the interest rate at which large banks borrow and lend among themselves. If investors think that this rate will rise, they’ll likely charge a higher interest rate, in advance, on their own lending. Second, they consider expected economic growth and inflation. If an investor charges a 3 percent annual interest rate for lending his money, but inflation looks to be 5 percent, he will lose money in real terms. Thus, if high inflation is expected, investors will charge higher rates. Investors also contemplate the risk of default. An investor will charge higher interest to a company that might go bankrupt. Finally, investors consider time. A bond that matures next year is usually less risky than a bond that matures in 30 years, because as time goes on, the chance that the unexpected will happen grows.

Bond markets are complicated, in part because all these factors work together. If inflation is high, for example, a healthy city with little debt could end up paying, effectively, a 7 percent interest rate on its debt: a 5 percent interest rate for inflation, plus an extra 2 percent for low risk. But if inflation is low, a distressed city with massive debt could end up paying a lower effective interest rate: 1 percent for expected inflation, plus an extra 4 percent for high risk. Markets try to discern these signals, which have beneficial effects on the real world: a city that has spent years ignoring its pension obligations actually benefits from investors charging it a higher interest rate, which encourages it to reform before it’s too late. Similarly, someone likely to default on an auto loan probably shouldn’t get a loan at all, because a default will hit her credit rating and end up costing her more money. A prohibitively high interest rate sends this signal, too.

Bond markets transmit information affecting not just individual decision makers but entire markets. If mortgage interest rates are too low, housing prices will rise too high, because people can borrow more to buy a house, jacking up prices. If interest rates are too high, though, entrepreneurs might hold off on borrowing to expand their businesses, harming people seeking jobs.

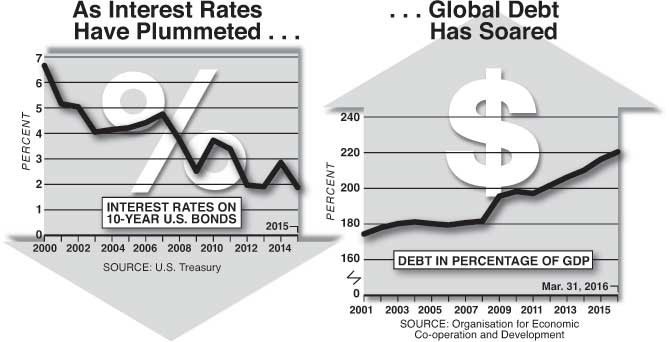

Even before 2008, government actions had distorted these bond-market signals. For decades, the government had increasingly depended on low interest rates to drive economic growth. In the 1980s, the Federal Reserve, which primarily sets global interest rates, rarely let its key rate fall below 6 percent annual interest. In the 1990s, it rarely fell below 5 percent. In the 2000s, it rarely rose above 5 percent.

The Fed kept rates low in part because inflation was low. When inflation is high, the Fed hikes rates to dampen the borrowing that may be leading to too much economic activity, which pushes up prices. But the Fed’s cutting rates and keeping them so low for so long hooked governments, businesses, and individuals on ever-cheaper debt. In 1983, America’s total debt—government, corporate, and household—was $13.3 trillion in today’s dollars. By 1993, it had reached $21.8 trillion; by 2003, $30.5 trillion; and by 2008, $39.4 trillion. Debt levels had tripled; yet the population had risen by only a third, and economic activity, as measured by gross domestic product, had only doubled. Similar imbalances afflicted other Western democracies.

“Banks have become impervious not only to market discipline but also to the full consequences of wrongdoing.”

Western governments depended on too-big-to-fail banks to push this debt to the American public. Allan Meltzer, a Carnegie Mellon professor, notes that in early-1950s America, large banks had only about a fifth of the industry’s market share. But that share has steadily grown, in part because the big guys could borrow at lower rates, forcing many smaller competitors out of the industry. According to a Milken Institute paper, the country’s 11 biggest banks held 30 percent of the country’s banking resources in 1983. By 2008, they held 60 percent. In 1983, the country’s financial sector had borrowed about $2.3 trillion in today’s dollars. By 2008, it had borrowed $20.2 trillion. (Banks borrow from their customers, via deposits; from large investors, via global markets; and from one another.) The banks, along with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government’s chartered mortgage companies, lent much of that money right back to consumers. In 1983, households had borrowed $4.3 billion. By 2008, they had borrowed $15.7 trillion. And long before 2008, Washington and other Western governments made it clear that they would save large banks whenever these activities got them into trouble. (See “Too Big to Fail Must Die,” Summer 2009.)

All this debt inflated bubbles, including the tech-stock bubble of the 1990s and the housing bubble of the 2000s. Yet by stoking demand for products and services that Americans would have been too poor to buy otherwise, it also generated jobs. Tens of millions of financial, construction, real-estate, car-manufacturing, retail, and restaurant positions increasingly depended on consumers who could borrow, whether with good credit or bad, jobs or no jobs. The global picture was similar. By 2008, the International Monetary Fund estimates, gross global debt had swollen to 220 percent of GDP, from less than 200 percent a decade earlier. For once defying the government planners, the financial markets decreed “enough” and shut down.

Instead of learning their lesson, governments repeated their mistakes. The United States and the rest of the West bailed out their banks after 2008. In the U.S., banks used government money to get even bigger. Wells Fargo bought Wachovia, the country’s fourth-largest bank, to become the second-largest bank. JPMorgan Chase acquired Washington Mutual. PNC absorbed National City. Too-big-to-fail makes sense from Western governments’ planning perspective: when your goal is to get people to borrow as much as possible so that they can keep spending, it’s necessary to indemnify lenders.

From a free-market perspective, though, it’s a disaster. Banks have become impervious not only to market discipline but also to the full consequences of wrongdoing. Regulators can’t substitute for an efficient market, which would allow bad banks to fail and good banks to thrive. Last fall, Wells Fargo announced that 5,300 of its workers, following incentives to bring in new business, had stolen customers’ personal information to invent fake new accounts for those customers—breathtaking systemic fraud. Yet the company paid only a $185 million fine, against more than $36 billion in annual profits. Meltzer observes that today’s large financial institutions are a big part of what he calls “factions”—not just in finance, but in health care and other key areas of the economy. “Getting control of the government. . . . It’s exactly what James Madison warned about in Federalist #10,” he says. Powerful corporations, in turn, have helped erect an “administrative state” that runs on opaque regulations rather than clear rules—shutting out would-be competitors without the resources to comply with those regulations. (See “It’s Not Your Founding Fathers’ Republic Any More,” Summer 2014.) “It didn’t start with Obama but it moved forward” during the Obama years, he says.

Bailouts remain the norm worldwide. In Britain, the government still owns the Royal Bank of Scotland, the nation’s largest bank. In late 2016, RBS failed a “stress test,” despite being government-owned. For the past year, Italy avoided forcing the world’s oldest bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena, to take losses on tens of billions of euros in bad debt, instead letting the bank stay in business despite its clear insolvency. The German government has reportedly pressured the U.S. government to go easy on Deutsche Bank, its own behemoth, in levying fines stemming from global money laundering, fearing that the penalties would scare investors. Coddled by government, banks have less incentive to compete efficiently.

One can’t call the big-banking dominance in the West the result of free-market forces. Ed Conard, a founding partner of Bain Capital and author of The Upside of Inequality, doesn’t think that free markets in banks exist or should exist. “The free market doesn’t work in banking,” he argues. It’s rather jarring for the West, decades into an era that supposedly unleashed unrestrained free-market forces, to learn that the industry that allocates capital for all other industries is basically a government utility.

After 2008, the Federal Reserve did something unique in nearly a century of rate-setting: it slashed its key interest rate to zero, where it remained until early 2016 (it’s now slightly higher). Other Western governments, encouraged by the Fed, have followed suit, with Europe going even further, adopting in 2014 a negative interest rate. That is: large financial institutions began paying to lend money—four-tenths of a percentage point—instead of paying to borrow it. In Japan, too, the main interest rate is slightly negative. The financial institutions don’t gain anything by paying to lend out money; rather, they’re forced to do so because they need someplace to put the money—they can’t, practically speaking, store hundreds of billions of banknotes or gold in vaults to avoid these fees, though some institutions have explored the possibility.

Some economists are unconcerned with super-low interest rates. They point out that the world has had implicitly negative interest rates in past periods of high inflation. When inflation was 10 percent, and interest rates less than half that, investors lost money, in inflation-adjusted terms, on their savings. “I don’t see why having low interest rates would make it hard to value capital,” says Deirdre McCloskey, until recently a professor at the University of Illinois. “It just makes it more valuable.” As interest rates shift, the world simply shifts with them, in this view. The price of the things that people can buy with cheaper borrowed money, from stocks to houses, goes up, and the world adjusts.

Some see low and negative interest rates as merely a symptom of the problem, not the problem itself. “Interest rates are largely set by the market,” says Conard. He calls the Federal Reserve “a price taker rather than a price maker.” That is, rates are low because of the global upheavals that trade and technology have caused. “The Germans have a surplus, the Chinese have a surplus, the Japanese used to have a surplus,” Conard says, speaking of the money that those nations earn from global trade. Investors from these countries prefer to keep their money in safe investments, such as U.S. government bonds, and that keeps interest rates down. “The Americans are scared,” he adds, and want to invest their money in supposedly safe debt, pushing demand for that debt even higher and pushing interest rates lower; the market “is going to drive the interest rate near zero no matter what [government] does.”

If that’s true—and it is at least partly true—Western governments should be pushing back against this powerful force, not exacerbating it. Moreover, a big difference exists between a 1 percent interest rate and a negative 1 percent interest rate. Negative rates toy with people’s psychology. If you tell me that you have two apples to sell, I’ll get it. If you tell me that you have negative two apples to sell, I might not understand, though you’re trying to say, in a mathematically accurate way, that you want to buy two apples. The entire underpinning of a rational financial system is based on the idea that the people with money to lend make a profit, or try to make a profit, from lending it. Sometimes, yes, inflation scrambles that system. But in those cases, a competent government tries to correct things, not make them worse.

In Europe, negative interest rates have changed behavior. Companies are paying their tax bills early, for instance, because they don’t also want to pay banks for keeping their money longer. Banks can’t make a profit on their traditional business because they’re stuck with the cost of holding their smaller customers’ money. Couldn’t they just charge their average savings-account holders, instead of paying them interest? European regulators think that it would make average Europeans nervous to see negative interest rates on their bank accounts. A practical concern exists, too: regulators worry that, if small depositors withdrew their money from the banking system and stored it, in banknotes, at home, such a practice would encourage theft. Small savers grasp that negative interest rates are a bad idea, even if central bankers don’t.

Ultralow and negative interest rates have distorted the bond markets. To keep rates low, central banks from the United States to Europe have purchased trillions in government bonds. The Federal Reserve also bought mortgage bonds, and the European and Japanese central banks keep buying corporate bonds. In 2008, the world’s major central banks held little more than $6 trillion in assets, according to Yardeni Research. Today, they hold nearly $17.8 trillion—more than 10 percent of the world’s borrowing. Japan’s central bank owns more than a third of the Japanese government’s long-term bonds.

This outsize government demand means that no free market in bonds really exists. That became clear last summer, when Britain and Japan tried to buy more of their respective government bonds and had trouble finding sellers: central banks had already bought so much that the supply was scarce. Meantime, other investors wanting to buy government bonds—or who must do so, required by law or by contracts to put their clients’ money in supposedly safe investments—had to pay far more than they would have liked, or buy something else.

Globally, over the summer, $13 trillion in high-quality debt traded at negative interest rates, meaning that investors had to look afar to find something that paid them a positive interest rate and was safe. “We lost the core of free markets when they decided they should keep the rates at zero” and below, says David Malpass, head of the Encima Capital consulting firm and an economic advisor during the campaign and transition to Donald Trump. “It was really harmful. . . . As the Fed started buying bonds, that fundamentally changed the character of financial markets away from market rates.” The European Central Bank buys $88 billion worth of bonds a month, both government and corporate. “But everyone just kind of glosses over it,” says Malpass. In October 2016, Europe, Britain, and Japan spent half a trillion dollars on bonds—a record.

The effects are clear. During the summer, Italy’s government sold $5.6 billion in 50-year bonds, at an interest rate of less than 3 percent—far lower than the rate at which Italy could borrow for two years’ time after the 2008 crisis, the Financial Times points out. Italy, one of Europe’s struggling peripheral economies, hasn’t shaped up since then. Yet global investors are essentially saying that, for the next half-century, inflation will remain low in Italy and that the country, with its aging population and inefficient labor force, will be just fine. More likely: some investors who bought the bonds hoped to sell them immediately at a higher price, as central banks created more demand.

Since 2008, American cities and states have also borrowed at record-low interest rates, even as it becomes clear that many cannot pay their long-term pension and health-care obligations. The Financial Times notes that “foreign investors are buying increasing amounts of the debt sold by US states and cities” because they can’t get any return at home. Such investors probably know nothing about the merits of the various cities and states; they’re only looking for some kind of positive return.

These distortions also affect corporate bonds. When the British central bank buys bonds in, say, Apple and McDonald’s, private investors have no way of signaling how safe or risky they think these companies are. It’s a strange strategy: Apple, for instance, is awash in cash (in part, European governments allege, because it doesn’t pay sufficient taxes). It doesn’t need to borrow more, at government-subsidized rates. Why, then, use state power to cut its costs further?

As people can’t earn a return on supposedly safe government and corporate bonds, they turn to the stock market, incurring higher risk. Companies have used cheap, borrowed money to buy up shares in their own stock—more than half a trillion dollars’ worth in 2015. This elevates stock prices—the firms haven’t created any breakthrough products to justify the higher prices—and encourages smaller investors to invest in stocks to take advantage of the rise. The Wall Street Journal reports that regulators are nervous that life-insurance companies and pension funds must take on greater risk because the government bonds and top-tier corporate bonds that they once relied on for solid returns have gotten too expensive. Stephen Winterstein, top strategist at Wilmington Trust’s municipal-research team, observes that, though U.S. city and state governments have benefited from decades of borrowing cheaply, they’re also having a harder time investing their pension-fund assets to make good returns. Over-expensive bonds and stocks drive investors into property, as well, inflating prices for people in global cities.

Finally, cheap debt continues to distort labor markets. In November, New York’s Federal Reserve branch reported that defaults on auto loans are rising. No wonder: subprime borrowers—people with credit scores below 620—have borrowed nearly $350 billion, surpassing in 2015 their prerecession peak. A Standard & Poor’s analysis of $1.6 billion in such loans found that 20 percent of borrowers defaulted. Such loans would not be made if interest rates were higher, because investors would not be able to compensate themselves for the risk; they’d have to charge unaffordable interest rates.

“In the U.S., total public and private debt stands at $46.3 trillion, nearly 18 percent higher, after inflation, than in 2008.”

Yes, loose lending standards have helped the American auto industry, and its jobs, recover from the 2008 crisis. In November 2016, automakers sold a record 1.3 million cars and SUVs. Permissive lending also underpins the so-called sharing economy, as low-wage drivers for the car-hire company Uber, for example, borrow to purchase their five-figure equipment. “Uber . . . will put more than 100,000 drivers on the road” this year, Bloomberg News reported in May 2016, by “dipping into the vast pool of people with bad or no credit.” Uber’s subprime-lending company “caters to people who have been rejected by other lenders.” Automakers have benefited from this mass-scale artificial demand for cars, based largely on low interest rates. But because of this government intervention, we have no way of knowing if building millions of new cars was the most productive use for those investment dollars.

One can pragmatically support low interest rates: they’ve allowed tens of millions of people to borrow money that they otherwise could not have borrowed, and thus kept millions of other people employed. Low rates bought time as well. From another perspective, though, the West failed to use this time to make necessary structural changes—especially changes that would make it less dependent on debt and imports and more reliant on saving and exports. Either way, one can’t call this a free-market economy.

The world has more debt today than ever: $152 trillion, according to the IMF. In the U.S., total public and private debt stands at $46.3 trillion, nearly 18 percent higher, after inflation, than in 2008. Consumers have shed some mortgage debt through foreclosures. But other consumer debt has risen by 23 percent, even faster than government debt. This isn’t traditional Keynesianism, where government borrowing makes up for private-sector cutbacks in a recession. It’s just lots of debt.

Today’s record-low interest rates are now taken for granted. The University of Chicago’s Thomas Coleman, a former hedge-fund executive, says that he worries about government distorting prices. “If you look back to Hayek,” he says, “he worried about governments controlling the market” and telling economic actors “what they could trade.” It’s very different today, he maintains, but also “hugely problematic and potentially damaging.” Coleman doesn’t know exactly which prices in the market are being distorted, but “I’m pretty sure that there is distortion,” he says, and “when you start distorting prices, you start distorting signals”—making it hard for economic actors to make sound decisions.

Most people don’t understand how bond markets work, but they do recognize that something’s askew with the global economy. That’s a big reason that Americans elected Donald Trump. Fittingly, after the election, interest rates on bonds began to rise, countering the signals that governments have been sending since 2008. Barely a month after the election, the amount of global debt trading at negative interest rates had fallen to $11 trillion from $13 trillion. It’s not clear why interest rates began rising. Investors may be nervous that Trump’s proposed tax cuts and spending plans could cause inflation, or they may think that these plans will ignite economic growth, which would, in turn, cause the Fed to raise rates.

One thing’s for sure, however: the West can’t keep borrowing like this. When this unsustainable situation comes to an end, its consequences won’t be the fault of free capital markets. Governments had to obliterate those markets to get this far.

Top Photo: Over-expensive bonds and stocks drive investors into property, inflating prices for people in financial centers like New York. (RICHARD B. LEVINE/THE IMAGE WORKS)